Not all sources of meaning are unambiguously positive. Rather, many people in the 17 publics surveyed also mention challenges they have faced – whether they be health concerns, lost jobs, insufficient income or difficult relationships. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic is referenced in each of the publics surveyed, sometimes as the reason for little to no fulfillment and other times as the source of personal reflection and growth.

COVID-19

The timing of the survey – around a year after many places began lockdowns but before vaccines were widely available – meant that COVID-19 was top of mind for some respondents. And, indeed, when asked where they find meaning in life, some made references to the global pandemic as part of their answers. This included any mentions of the coronavirus itself, as well as pandemic-related lifestyle changes such as travel restrictions, mask-wearing or quarantining.

For some, the pandemic has provided an opportunity for reflection on meaning in life, such as for a French woman who said, “Lockdown helped me settle down and reflect, and appreciate my life.” Others referenced their society’s pandemic response; for example, one woman in Taiwan said that “Taiwanese people are very united during serious incidents, such as pandemics or earthquakes.” In some instances, respondents said that what gives them meaning in life has also helped sustain them through the pandemic or referred to experiences related to COVID-19 to illustrate what they find meaningful. One such response came from an American woman who said, “Spending time with loved ones. With COVID, that generally means phone calls and Zoom sessions.” Still others – like a Greek woman who said, “Nothing satisfies us. We go nowhere, we do not go outside. We have been locked up for more than a year” – said they are unable to find meaning due to the pandemic.

No more than one-in-ten mentioned the pandemic in any of the 17 publics surveyed. Those in Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden are tied for most frequent mentions of COVID-19, with 8% of their respondents bringing up the pandemic. France follows closely at 7%, and the U.S. and Taiwan are next at 6%.

“In the face of recommended COVID restrictions, I have found a new love of nature, outdoor activities and ranch animals; especially horses.” –Woman, 59, U.S.

For the most part, people were equally likely to mention the coronavirus in their response regardless of age, gender, income level, political ideology or educational attainment. In some places, those who mentioned any dissatisfaction in life were more likely to mention the pandemic. For example, 46% of Swedes who mentioned something negative also mentioned COVID-19. In contrast, only 6% of those who did not mention something negative also brought up the pandemic. In most other places surveyed, too, those who mentioned something negative were significantly more likely to reference COVID-19 than those who did not say something negative. The notable exceptions were all in the Asia-Pacific region. In Taiwan, South Korea, New Zealand, Japan and Australia, while few mentioned negative things at all, almost none of these references were about the pandemic. Outside of Japan, each of these other publics stands out for their relative satisfaction with how their governments have handled the pandemic.

Despite the context of the global pandemic, in most places surveyed those who mentioned health in their answer were no more likely to mention COVID-19. The U.S., however, is a strong exception: 20% of those who mentioned health also mentioned COVID-19, compared with only 7% of those who did not mention health but mentioned the global pandemic.

In six publics, those who say their life changed at least a fair amount because of the pandemic were also more likely to bring up the pandemic. The difference is greatest in Italy and France, where those who feel at least somewhat affected by the pandemic were 6 percentage points more likely than those who feel not too or not at all affected to bring up the pandemic. The same relationship appears in the U.S., Germany, the Netherlands and Taiwan.

Challenges faced as people search for meaning

Despite being asked about what makes life meaningful and fulfilling in a positive sense, some people nevertheless mention challenges or difficulties that have interfered with their search for happiness.

Some struggle to think of anything meaningful in their lives. “To be honest, it’s hard to find meaning because the things that used to bring joy feel more hollow as I’ve gotten older. Everything seems either frivolous or like drudgery. I try to skateboard when the weather is nice and that’s okay, but still not as fun as it used to be,” remarked one American man. Others are more particular, describing difficulties with their living situation, finances, health, career or relationships. “Once I’ve paid all the bills I don’t have anything left. There should be more support for single-parent families,” complained a woman in Belgium. “I lack basic health care. I can’t find health benefits,” said one man in Greece.

In many cases, respondents’ negative remarks focus not on personal difficulties but rather ongoing social and political turmoil, including the global pandemic. “Between coronavirus, politics and climate change, there is a lot of pressure and it’s hard to see a future … we’re all under pressure, exhausted, stressed and waiting for something [to] happen to make things better,” explained a man in Spain. As a woman in the U.S. put it, “I think our world has gotten more and more troubling and [is a] harder place to live. I don’t think it will ever get better.”

“Almost nothing, I have no job, there is no justice and I am weak because I live with two [people] with disabilities. Nothing is satisfying and fulfilling unfortunately because of the little [economic] aid that I receive for care workers.” –Woman, 59, Italy

People also describe challenges related to the inability to afford things or find jobs, frustrations with their political system, concerns about climate change, worries about the next generation’s ability to succeed, personal loss such as widowhood and more. In some cases, people mention personal difficulties they have faced in the past and describe finding meaning in the process of overcoming them. (While respondents might highlight more than one thing that negatively affected them in a given response, each response was only coded for the presence or absence of a complaint or challenge.)

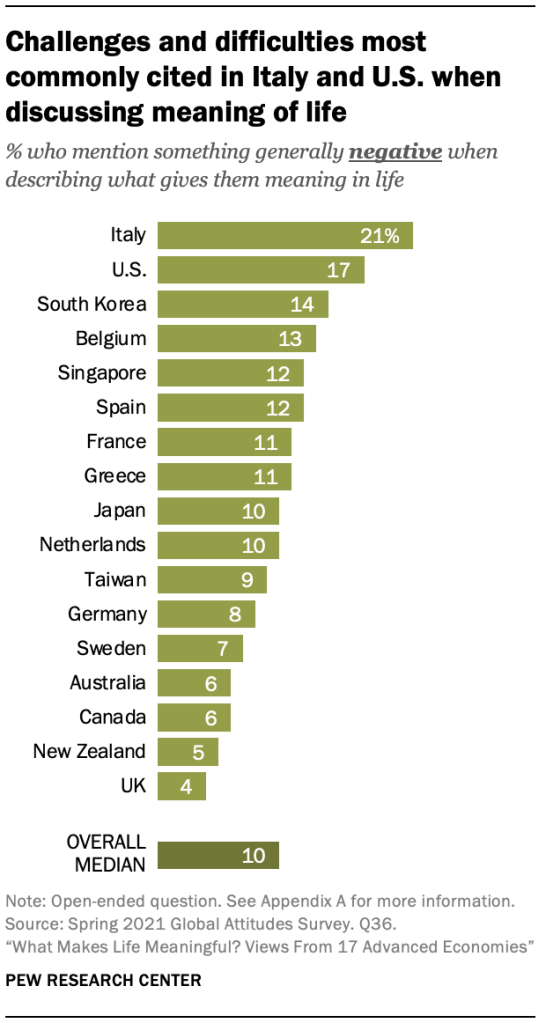

Mentions of negative situations are not particularly common overall – a median of 10% of people cite them – but there is wide variation across the publics surveyed. In the UK, just 4% of adults mention difficulties or challenges. On the other hand, such responses are notably more common in Italy (21%), the U.S. (17%) and South Korea (14%).

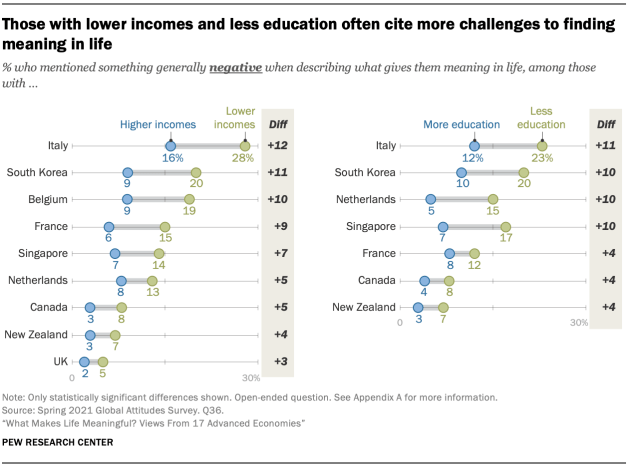

Those with lower levels of education and income tend to cite more challenges in many places. In South Korea, for example, those with less than a postsecondary education are twice as likely as those with a postsecondary degree or more to cite a challenge – and the same is true among South Koreans who have less than the country’s median income relative to those who are at or above the median income.

Similarly, in around half the places surveyed, those who think their country’s economy is doing poorly are more likely to mention a hardship than those who think it is doing well. Once again taking South Korea as an example, 17% of those who think the South Korean economy is in bad shape mention something negative when asked about their sources of meaning, compared with 8% among those who think it’s in good shape.

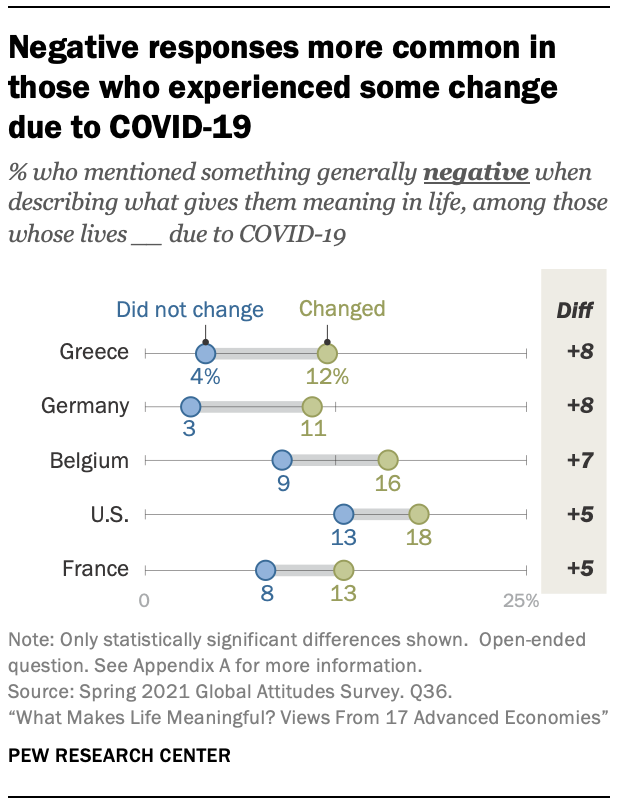

In five of the publics surveyed, those who say COVID-19 changed their lives a great deal or a fair amount are more likely to say something negative when asked about meaning in their life.

Responses that discuss society, places and institutions also coincide with greater negativity in the U.S., Italy and Spain. For example, in the U.S., difficulties or challenges are brought up by nearly half (49%) of those who mention society, institutions, politics or something about where they live, compared with 15% of those who discuss other topics but not society. South Korea and Taiwan, however, stand out for the opposite relationship: In both of these publics, those who mention society are less likely to mention negative things than those who do not mention this topic.

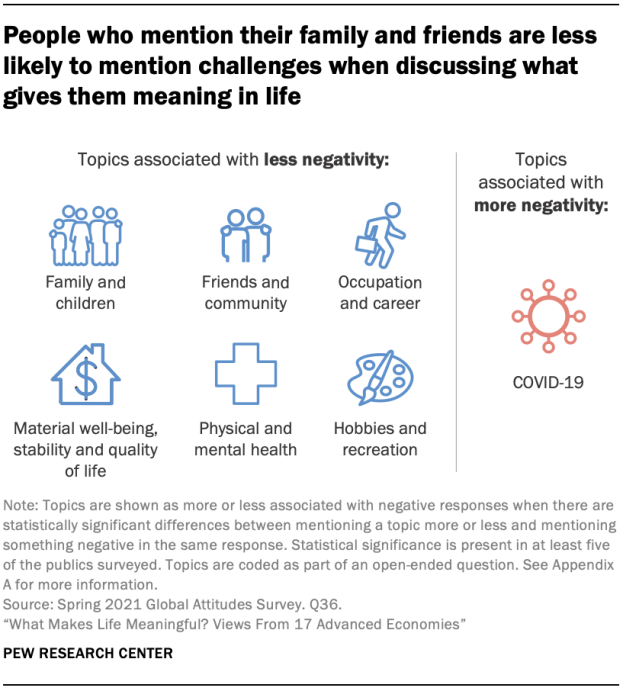

On the other hand, a variety of other topics are associated with fewer mentions of negative circumstances in the majority of the publics surveyed. One such topic is family, which appears to provide a buffer against personal challenges and difficulties. In 16 of the 17 publics, those who mention their family are substantially less likely to mention something negative in their responses. For example, 23% of Greeks who do not discuss family or children say something negative, compared with just 2% of those who do mention their family or children. Even in the context of the global pandemic, one Greek woman reflected on how the hardship had actually strengthened her family’s relationship: “The good thing at this time is that because of the pandemic, my family has bonded more, and our relationship and also our state of mind as family members has evolved. As parents, we listen to our children more and our children reach adulthood more quickly.”

To a lesser extent, friends, community and other relationships are also associated with fewer mentions of something negative. In 13 publics, those who mention their friends are less likely to mention something negative as are those who don’t mention friends.

People who mention their occupation or career are also less likely to mention personal difficulties or challenges in nine of the 17 publics surveyed. In Japan, just 1% of those who discuss their job or career mention any difficulties or challenges, compared with 12% of those who do not mention anything about work.

Recreation is also associated with fewer mentions of challenges or difficulties in several publics surveyed. In Japan, for example, just 1% of those who mention hobbies or recreation report something negative in their lives, compared with 12% of those who do not mention any hobbies or pastimes.

In four of the Asia-Pacific publics surveyed (South Korea, Taiwan, Japan and Singapore), as well as France, those who mention their material well-being, stability and quality of life are less likely to mention difficulties or challenges in their lives. In South Korea, just 2% of those who bring up the topic say something negative, compared with 19% of those who do not mention their standard of living. In the U.S., the pattern is reversed.

Interactive: Where People Around the World Find Meaning in Life

Interactive: Where People Around the World Find Meaning in Life