From work to travel to personal hobbies, people across the 17 publics surveyed draw meaning and fulfillment from the activities that make up their daily lives. This is particularly the case when it comes to people’s occupations and careers, which are a top-three source of meaning in many publics. People mention finding meaning in myriad aspects of their work, such as the mission of their own profession, their coworkers, or the sense of personal growth it provides them. On the other hand, some people – particularly older adults – find meaning in the absence of work: retirement. People also rely on their personal hobbies, education, volunteer work and travel for a sense of purpose, referencing everything from listening to music to international trips.

Occupation and career

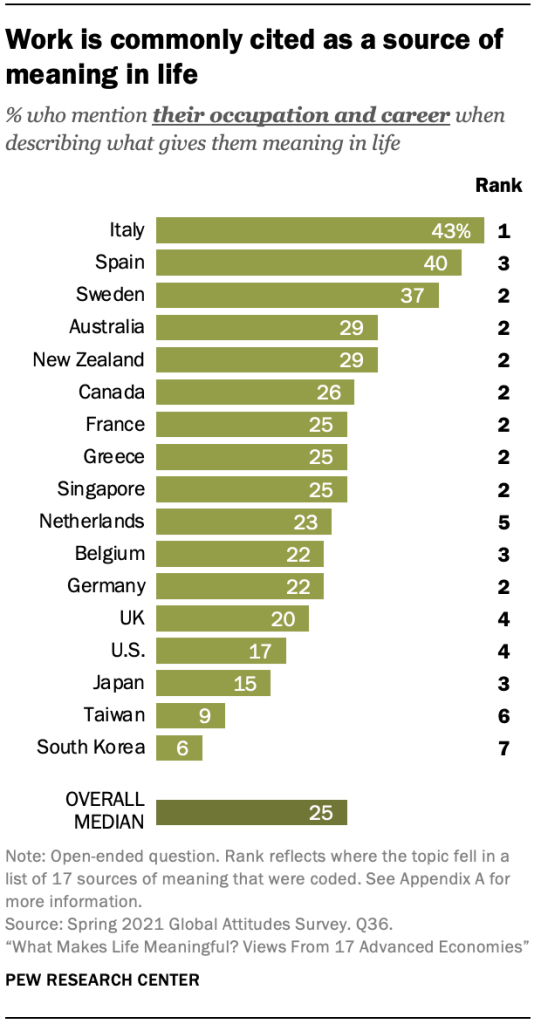

Work is one of the most common sources of meaning for adults around the world: A median of 25% across the 17 publics mention their job, career or profession. In 12 of the 17 publics surveyed, work is among the top three most mentioned topics – and in Spain, it ranks even higher than family and children.

As one Italian man put it, “In accordance with the Italian Constitution, to have a job and dignity. Most of all to have a job, because without a job it is difficult to have dignity.” “I have a job I like and that is fundamental for a person,” explained one Spanish woman.

Many emphasize how work provides them with a sense of accomplishment and personal growth. As one man in the Netherlands explained, “The most important thing for me is work. I think it is very important to build my career, to build my life, so that I’m doing better and better. And the way to do that is to take a lot of personal responsibility and work hard.” Another man in Japan remarked, “I got the job that I wanted, so being able to keep doing that. I’ll have left my mark when I look back on my life.”

On the other hand, some people mention difficulties or challenges in their professional life. “In my job I don’t feel satisfied because they don’t give me personal days,” explained one Italian woman.

Like with finding meaning in family, people between the ages of 30 and 49 are typically the most likely to find meaning in their job or career. For example, in Italy, 59% of those ages 30 to 49 say work gives them meaning, while roughly half or fewer of any other age group agree. Still, mentions of work are quite prominent among most other age groups, though notably lower among those 65 and older.

“I run two companies and work as a salesperson. I work with producing and selling groceries. Work is what is most satisfying right now. I find it very fun and work about 100 hours per week.” –Man, 21, Sweden

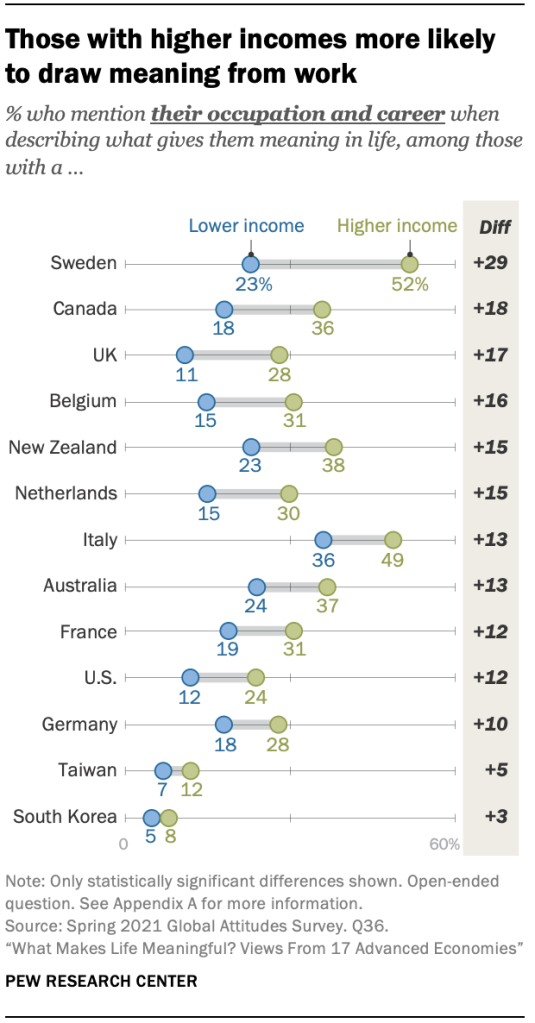

Wealthier and more educated adults are also more likely to mention finding meaning in their work. In many cases, higher earners are twice as likely or more to mention their jobs as lower earners. For example, 28% of those earning above the median income in the UK mention their job or career, compared with 11% of those with incomes at or below the median. Similar differences also appear between those with and without postsecondary degrees. In the U.S., work was brought up by roughly a quarter (26%) of those with college degrees, but just 11% of less educated adults mentioned work.

Retirement

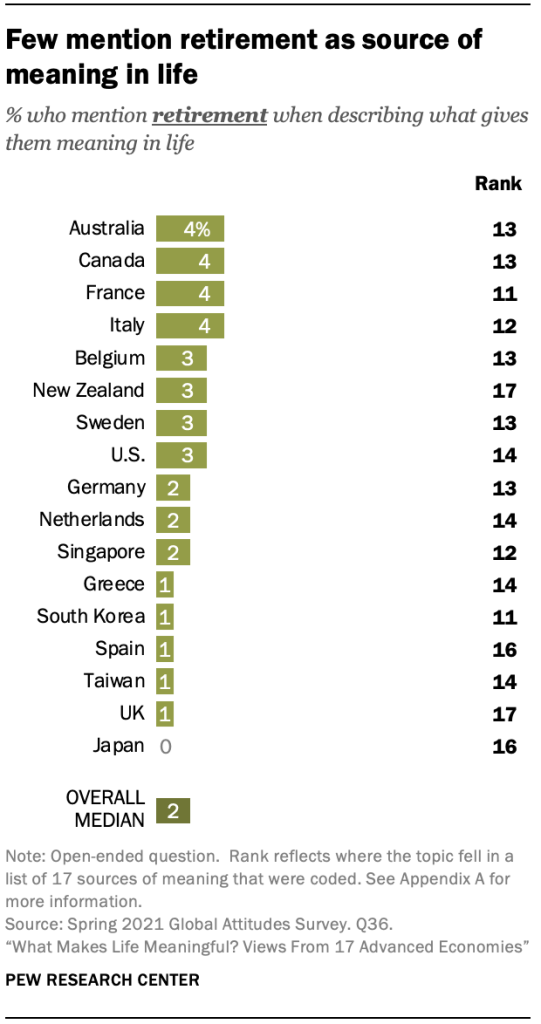

When describing what gives them meaning and satisfaction in life, some mention enjoying – or looking forward to – their retirement years, though in no public surveyed do more than 4% mention it. Those who do focus on retirement tend to emphasize how it affords them the freedom to do more of what they enjoy. “I have more time for me. I’m exploring new options, new things, and I’m enjoying the next chapter in my life,” explained one Australian woman. “[I] don’t have financial stress. I can go traveling and visit around. Life is very convenient,” said another woman in Taiwan. Others enjoyed the slower place in life, like a man in New Zealand who explained, “My lifestyle is very slow these days so I am satisfied.” And some responses were more succinct, like the man in the UK whose entire response was simply the remark, “The fact that I no longer work.”

“I’m retired so I don’t have to get up early, I’m free and can do whatever I want. There’s nobody to tell me what to do.” –Man, 62, Belgium

Unsurprisingly, retirement is more commonly mentioned by older adults in nearly all of the publics surveyed. In Germany, for example, 9% of those ages 65 and older mention their retirement, while almost no one ages 64 and under brings it up.

Hobbies and recreation

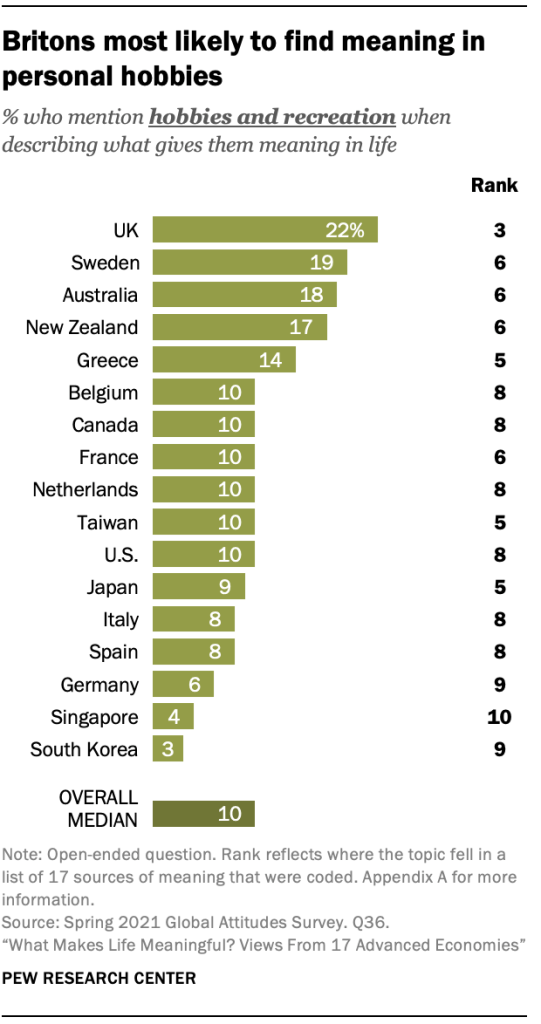

Across the 17 publics surveyed, a median of 10% mention finding meaning in personal hobbies and recreational activities, ranging from a high of 22% in the UK to a low of 3% in South Korea. In the UK, hobbies are the third most commonly cited source of meaning, following only family and friends. In Greece, Japan and Taiwan, hobbies rank in the top five sources of meaning.

Respondents highlight myriad types of recreational activities. One Briton, for example, explained that he enjoys “watching movies and having access to internet, football, music, entertainment and museums.” Others reference things like reading, playing music, attending cultural events or simply relaxing and spending time at home.

Many people cite pastimes that allow them to spend time outdoors, often connecting their hobbies with an appreciation of nature. One Canadian, for example, replied that she gets meaning from “… being able to go outside [and] going on walks” while others highlight the benefits of being able to surf, ski or bicycle in the beautiful surroundings.

“Creating books, writing, I do particularly enjoy capturing what I see and it’s quite [fulfilling] for me. Having something to collect as well. I collect cameras and electronics, I find that an [interesting] hobby.” –Man, 23, Singapore

In eight publics surveyed, young people are significantly more likely to cite personal hobbies as meaningful parts of their lives. This difference is greatest in Greece, where roughly three-in-ten 18- to 29-year-olds reference recreational activities, compared with 7% of those ages 65 and older. In five publics, men are more likely to mention their hobbies than are women, including Australia, where 14% of women do so compared with 23% of men. In some places, those on the ideological left and those who are more educated are also more likely to mention hobbies than those on the right and those with less education, respectively.

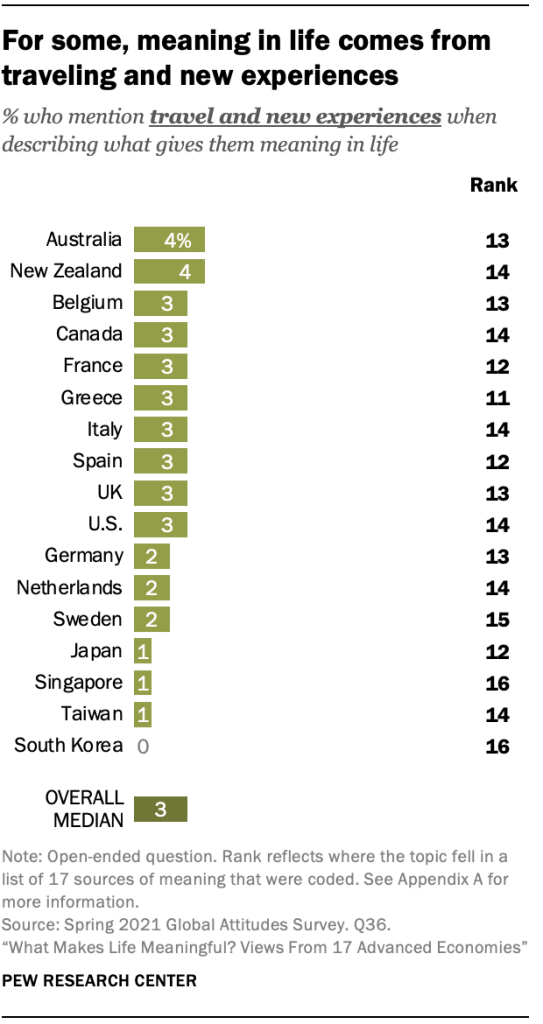

Travel and new experiences

Occasionally, people mention traveling and having new experiences as part of what gives their life meaning. One French man, for example, explained, “I have a full and meaningful life, and I have traveled a lot and had lots of experiences, so compared to others I think I have a wonderful life.” Likewise, a Japanese woman explained that “I think I have a pretty good life traveling to many countries with my husband, kids and grandkids.”

In all publics surveyed, travel is mentioned infrequently. These mentions show up most often in Australia and New Zealand, with 4% in these places bringing up traveling and having new experiences. Only 1% in Japan, Singapore and Taiwan do the same, and virtually no one in South Korea brings up travel. This makes travel the least frequently mentioned source of meaning in South Korea (along with pets). For other publics, travel does not make it into the top 10.

Some people indicate they find meaning from travel within their own country, and others specify international travel and encountering different cultures as something they find satisfying. One man in Spain said that he finds it meaningful “to have more freedom to travel the world, [with] ease of movement between countries, not only between European Union countries but also others.”

“… I travel around the world and have been to a lot of places. I can see different things in different countries.” –Man, 24, New Zealand

In four countries, including the U.S., those with higher incomes are somewhat more likely to mention travel as a source of meaning than those with lower incomes. For example, in the U.S., 6% of people with incomes at or above the national median mention travel as something meaningful, compared with 2% of those with lower incomes.

Some respondents also mention travel in the context of COVID-19, bemoaning the inability to travel given current restrictions. One woman in the U.S. declared, “It’s been more stressful at work because of the pandemic. What keeps me going is hope, hope that one day I will be able to get on a plane again for vacation and leave this country.”

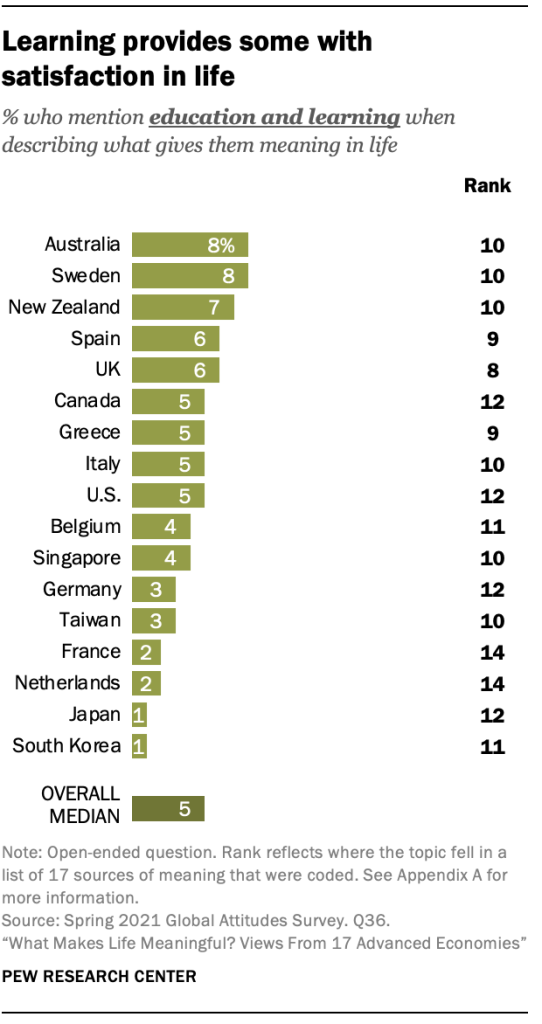

Education and learning

Some respondents also mention education and learning when discussing what provides meaning in their lives. In these cases, people mention attending university, staying informed and the pursuit of knowledge more generally. For one German woman, meaning in life comes from continuous learning: “Life is about learning new things, about progress, and staying curious.” Another Dutch man instead referenced his formal education: “I started university in the Netherlands. I am very happy about that. Because I am a refugee, I didn’t think I could go to university, but it turned out to be possible. It’s great that it’s possible.” In a handful of places, those on the ideological left are also somewhat more likely to mention learning than those on the right.

Fewer than one-in-ten bring up education in all publics surveyed. Education comes up most frequently in Australia and Sweden, where 8% refer to learning in the context of meaning in their lives. Similar shares also bring up learning in New Zealand. In most places, education is roughly the 10th most mentioned source of meaning.

“I view life as an endless opportunity to learn and be informed. Self-discovery. We can do little for the world, so we should start by working on ourselves first. I find this journey of discovery fulfilling.” –Man, 54, Italy

Across all places surveyed, younger adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely than older adults 65 and older to bring up education. For instance, 31% of Swedish adults under 30 bring up learning while only 1% of Swedes 65 and older do the same.

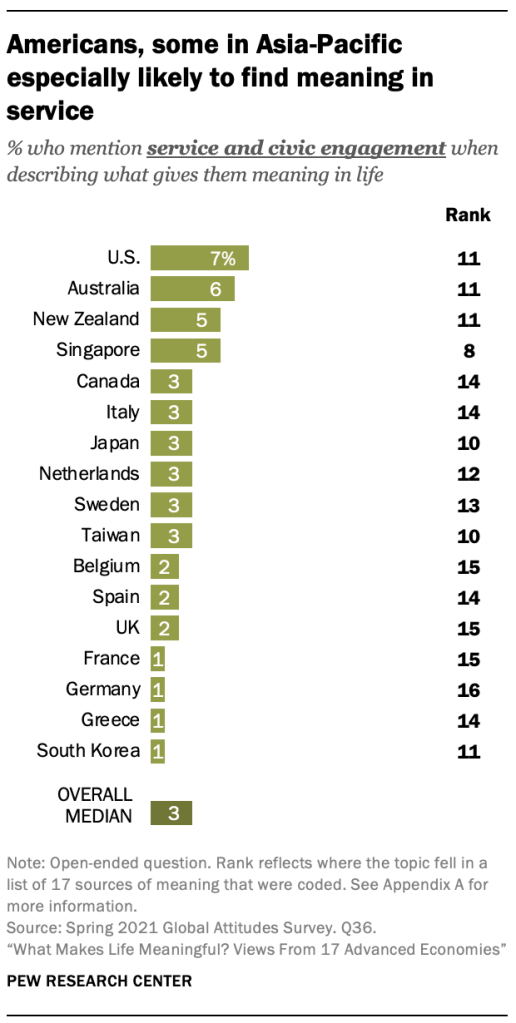

Service and civic engagement

Service to the community and civic engagement are part of a meaningful life for some people, ranging from a high of 7% who say this in the U.S. to a low of 1% in France, Germany, Greece and South Korea. Only in Singapore, Italy and Taiwan did service rank as a top 10 source of meaning.

Some people speak in general terms about the benefits of service and trying to make the world a better place. For example, one American man stated, “I feel it is important to treat people with kindness and respect, to work to correct injustices, to encourage people to use their talents in a positive way, and to bring good cheer into people’s lives. In short, to have a positive impact on the world.”

Others explicitly focus on the types of service that they do, like specific volunteer activities or work with particular causes. One Australian woman shared that she “started off doing a lot of volunteer jobs looking after the farms during the drought, so giving the farmers respite and at no charge whatsoever.” A man from France said, “Volunteering during the pandemic brings me a lot of satisfaction, it’s my way to contribute.”

“I raise my grandkids to be aware of how to avoid wasting food, and to recycle. I volunteer, giving mothers guidance about buying local and cooking their own meals, instead of buying industrial products.” –Woman, 70, Belgium

In some countries, people with more education tend to be more likely to say they draw meaning from some type of community engagement or service. In Australia, 8% of people with at least a postsecondary degree include community service in their answer about what gives them meaning, compared with 4% of those with less education.

Interactive: Where People Around the World Find Meaning in Life

Interactive: Where People Around the World Find Meaning in Life