But majorities say next generation will be worse off financially

This analysis focuses on views of the economy and the financial futures of the next generation in 17 advanced economies around the world. For non-U.S. data, the report draws on nationally representative Pew Research Center surveys of 16,254 adults from March 12 to May 26, 2021, in 16 publics. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

In the United States, we surveyed 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in the U.S. survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

This study was conducted in countries where nationally representative telephone surveys are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

To account for the fact that some publics refer to the coronavirus differently, in South Korea, the survey asked about the “Corona19 outbreak.” In Japan, the survey asked about the “novel coronavirus outbreak.” In Greece, the survey asked about the “coronavirus pandemic.” In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Taiwan, the survey asked about the “COVID-19 outbreak.” All other surveys used the term the “coronavirus outbreak.”

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses. See our methodology database for more information about the survey methods outside the U.S. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology

As the global economy shows signs of rebounding, positive assessments of the economic situation have risen in several major advanced economies since last year. Positive views of the economy have sharply increased in countries like Australia and the United Kingdom. Yet, many in Spain, Italy, Japan, France, Greece, South Korea and the United States continue to see their overall economic situation as bleak.

Despite an uptick in some places, many say that children will be worse off financially than their parents, according to a new Pew Research Center survey conducted this spring in 16 publics and in the U.S. this past February.

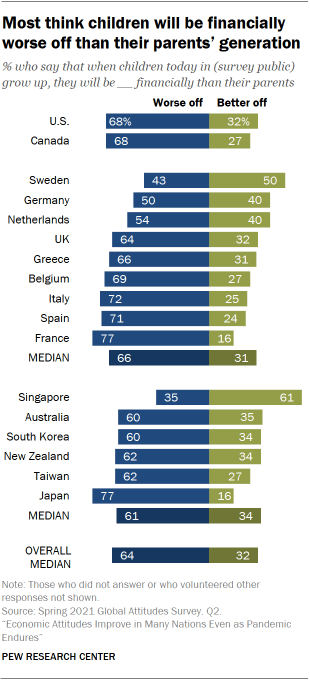

Across the 17 publics, a median of 64% say that when children grow up, they will be worse off financially, while about a third (32%) say that children will be better off than their parents’ generation. Only in Singapore and Sweden do half or more hold this optimistic view.

In the U.S., fully 68% think children will be worse off than their parents. The most pessimistic publics surveyed are France and Japan, where 77% say children will be worse off.

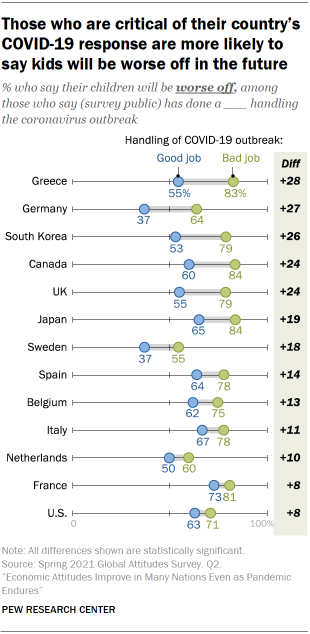

The survey also finds that people who say the coronavirus crisis has been mishandled by their government and those who say the economy is failing to recover in ways that show the weaknesses of their economy are more likely to say that the current economic situation is bad and that children will be worse off financially than their parents.

These are among the findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted from Feb. 1 to May 26, 2021, among 18,850 adults in 17 advanced economies.

Accompanying this report is an interactive analysis of the economic status of households around the world: “Are you in the global middle class? Find out with our income calculator.”

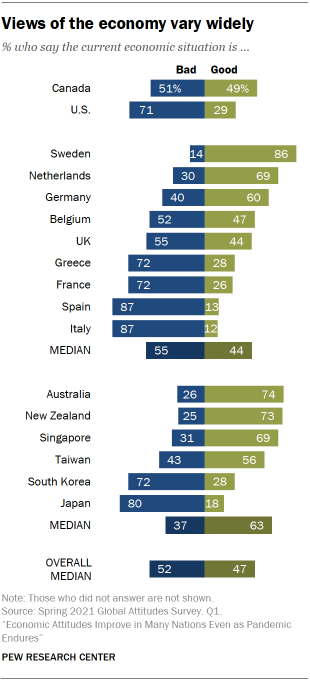

Views of the economy vary internationally

Overall views on whether the national economic situation is good or not vary greatly across the 17 publics surveyed. A median of 52% say that the current economic situation is bad, while a similar share (47%) say it is good.

Majorities assess the economy positively in northern European countries such as Sweden (86%), the Netherlands (69%) and Germany (60%) as well as in Singapore (69%) and Taiwan (56%). About three-quarters of those in Australia and New Zealand, where COVID-19 cases have remained relatively low, say the economy is good. (Note: This data was collected before recent lockdowns in Australia to curtail the spread of the coronavirus’ Delta variant.)

But eight-in-ten or more in Spain, Italy and Japan say the economic situation is bad in their country, as do seven-in-ten or more Greeks, French, South Koreans and Americans.

In Belgium, the UK and Canada, views on the national economy are nearly evenly split, with slightly higher percentages saying that the economy is bad.

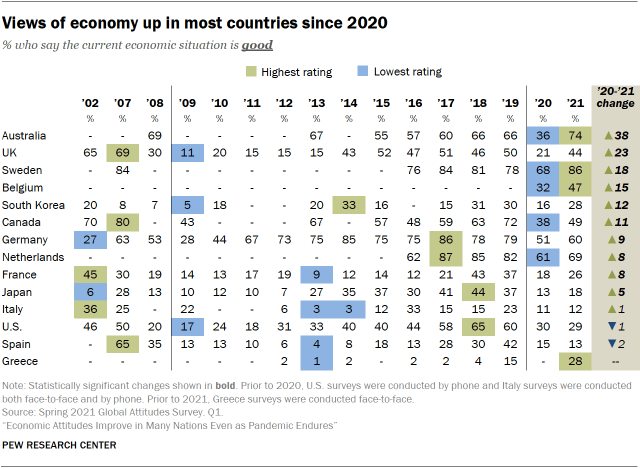

Among many publics, views of the national economy are more positive this year than last year. Positive assessments of the economy have risen the most in Australia, where 74% now say the economic situation is good, compared with only 36% in 2020. Positive views also rose in Sweden and the Netherlands, but even in 2020, majorities in these two countries still said the economy was good.

Despite the global economic downturn the coronavirus pandemic has wrought, views of the national economy are as positive as they have been since surveying began in Sweden in 2007 and Australia in 2008 – two countries that initially took very different approaches in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak.

While overall attitudes have grown more positive over the past year, the shares who say the economy is good have not recovered from their pre-pandemic highs in many countries. For instance, positive assessments of the economy in Canada rose 11 percentage points over the past year, from 38% to 49%. But in 2019, prior to the coronavirus outbreak, 72% had said the economy was good.

In most publics surveyed, women are more likely than men to say the economic situation is bad. But, in most of the 17 publics surveyed, there are no significant differences in economic outlook when it comes to age or education.

In most publics surveyed, those who support the governing party or ruling coalition are more likely to say the economy is good compared with those who do not support the governing party. While the U.S. portion of this survey was conducted immediately following the inauguration of President Joe Biden, a more recent U.S. survey has found a similar relationship between partisanship and views of the economy among Americans as well.

In most of the publics surveyed, views on the economy are related to respondent assessments of their government’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak. Those who think the outbreak has been dealt with well are more likely to say the economy is good. This is particularly the case in Germany and Canada, where those who say the outbreak has been handled well in their country are 38 percentage points more likely to say the economy is good compared with those who say the outbreak was handled poorly.

Especially when it comes to economic recovery in the wake of the pandemic, the survey finds that views vary widely, with a majority in the U.S., Japan and much of Europe critiquing their economic system’s durability. And skepticism of the state of recovery has colored views of the current economic situation. In all publics surveyed, those who say their national economy is recovering from the effects of the coronavirus in ways that show the strength of their economic system are far more likely to say the economy is currently good than those who point to their economy’s weaknesses.

And in 11 of the publics surveyed, those who say the coronavirus pandemic has changed their life not too much or not at all are more likely to rate the economy positively than those who say their life has changed a lot or somewhat.

Large shares are pessimistic about their children’s financial future

The coronavirus pandemic has been predicted to have wide-sweeping effects on the future of children around the world, particularly when it comes to education and economic outcomes. When respondents in 17 publics were asked how they think children will fare when they grow up, the prevailing view is that children will be financially worse off than their parents. More than two-thirds say this in France, Japan, Italy, Spain, Belgium, the U.S. and Canada.

A median of roughly a third (32%) say children will grow up to be better off than their parents where they live, with respondents in Singapore (61%) and Sweden (50%) standing out as particularly optimistic.

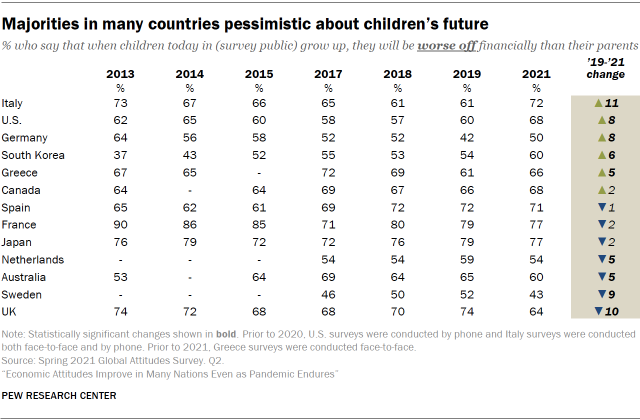

In some places, pessimism has markedly increased since before the COVID-19 outbreak, while in others, it has tempered. Respondents in Italy, the U.S., Germany, South Korea and Greece are now more pessimistic than they were in spring 2019, with Americans and South Koreans more pessimistic now than in any other year when the question was asked. However, respondents in the UK, Sweden, Australia and the Netherlands are more positive on their kids’ prospects now than in 2019. In fact, pessimism for their children’s future in Sweden and the UK is at its lowest point since the Center began asking this question in each country.

In the U.S., respondents of all political leanings are broadly pessimistic about the future of children, with views among conservative Republicans changing dramatically over the past year. In March 2020, 36% of conservative Republicans and Republican-leaning independents said children in the U.S. would be worse off than their parents. About three-quarters (76%) say so now, a 40-point increase.

When it comes to expectations for children’s futures among the publics surveyed, there are few consistent differences by age, education, income or ideology. In a handful of locales, women are more pessimistic than men, with the largest such difference in Belgium (75% of women vs. 61% of men say their country’s children will be worse off).

Those who say the current state of their economy is generally bad are far more likely to believe their children will be worse off in the future. In all publics surveyed, there are double-digit differences in pessimism between those who say their economy is good and those who say it is bad. In Taiwan, the difference is 42 points – 85% of those who think their economy is bad also think their children will be worse off, while 43% of those with positive views of their economy say their children will be worse off.

The survey finds that respondents tended to give high praise to the coronavirus response where they live, especially in the Asia-Pacific. But praise for the COVID-19 response is not uniform, and those who say the response has been bad are far more pessimistic about children’s futures there. There are large differences in both Greece and South Korea, where majorities approve of their local pandemic response, as well as in Japan and Spain, where majorities say their country has done a bad job dealing with the outbreak.

In a handful of publics surveyed, those who say their own life changed due to the pandemic (either a great deal or a fair amount) are more likely to say their children will be worse off. In Taiwan, roughly seven-in-ten of those whose lives were affected in this way are pessimistic, while just half of those whose lives did not change say the same. There are similar divides in the UK, South Korea, Canada and Australia.

Dissatisfaction with their economy’s recovery from the pandemic has also fed into respondents’ pessimism for the future. In nearly all publics surveyed, those who say their economy is failing to recover from the pandemic in ways that show weaknesses of their system are far more likely to say their children will be worse off than their parents. There are differences of 30 points or more on this issue in Greece, Canada and South Korea when compared with those who say the recovery has been a demonstration of economic strength.

Are you in the global middle class? Find out with our income calculator

Are you in the global middle class? Find out with our income calculator