Publics disagree about whether restrictions on public activity have gone far enough to combat COVID-19

This analysis focuses on public attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemic in 17 advanced economies in North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific. For non-U.S. data, the report draws on nationally representative surveys of 16,254 adults from March 12 to May 26, 2021, in 16 publics. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. The overall findings include trend analysis of the 13 countries surveyed in both 2021 and the summer of 2020.

In the United States, we surveyed 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

This study was conducted in countries where nationally representative telephone surveys are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

To account for the fact that some publics refer to the coronavirus differently, in South Korea, the survey asked about the “Corona19 outbreak.” In Japan, the survey asked about the “novel coronavirus outbreak.” In Greece, the survey asked about the “coronavirus pandemic.” In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Taiwan, the survey asked about the “COVID-19 outbreak.” All other surveys used the term the “coronavirus outbreak.”

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses. See our methodology database for more information about survey methods outside the U.S. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology.

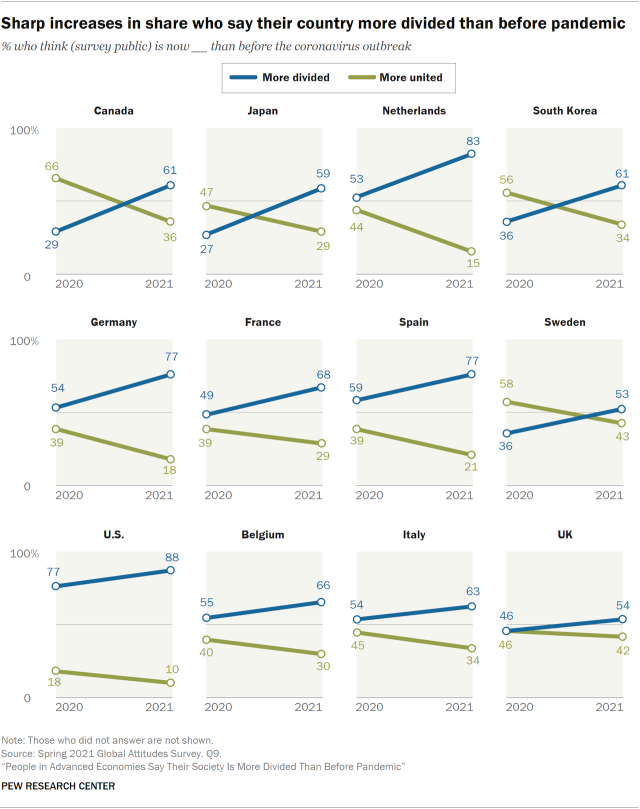

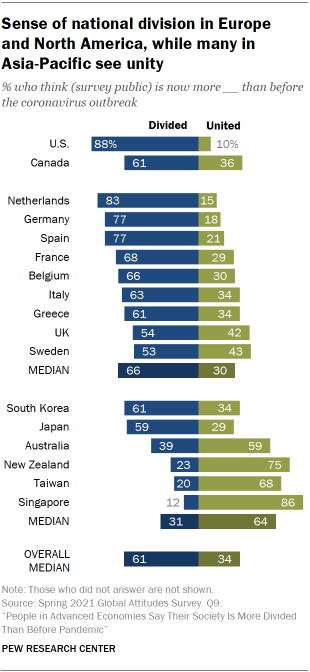

As the coronavirus outbreak enters its second year disrupting life around the globe, most people believe their society is now more divided than before the pandemic, according to a new Pew Research Center survey in 17 advanced economies. While a median of 34% feel more united, about six-in-ten report that national divisions have worsened since the outbreak began. In 12 of 13 countries surveyed in both 2020 and 2021, feelings of division have increased significantly, in some cases by more than 30 percentage points.

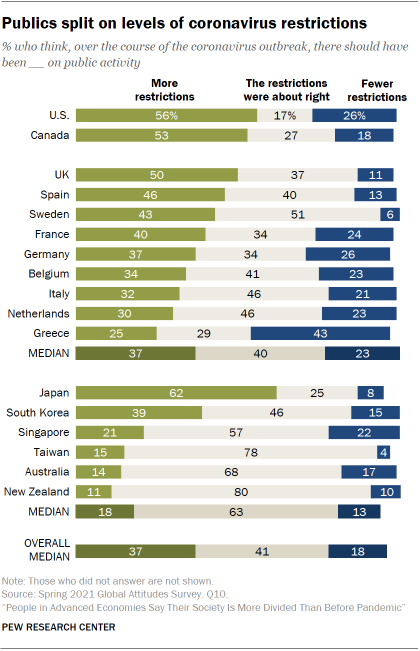

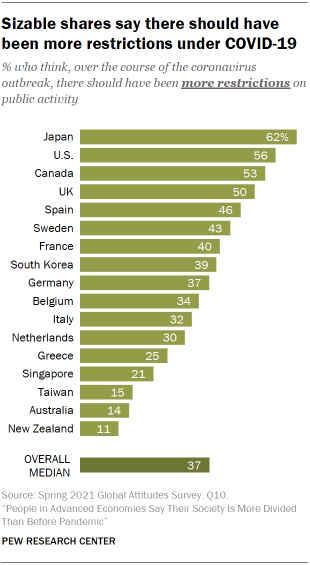

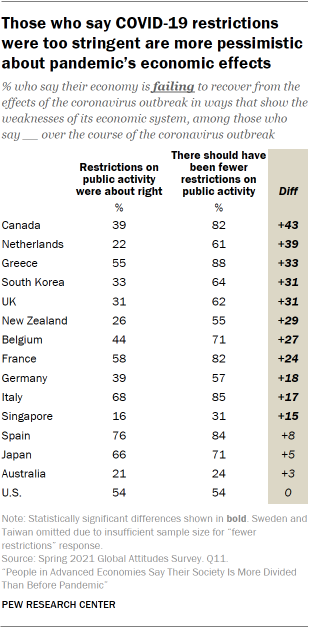

One source of these divisions manifests in how people view the social limitations they faced throughout the pandemic, such as stay-at-home orders or mandates to wear masks in public. Overall, about four-in-ten express the opinion that over the course of the pandemic, the level of restrictions on public activity has been about right. A nearly equal share believes there should have been more restrictions to contain the virus. A minority in most publics think there should have been fewer restrictions.

The Asia-Pacific region stands out: Publics there are most likely to think restrictions on social activity were about right, with a median of 63% holding that view. Those in North America and Western Europe, on the other hand, more frequently believe that restrictions did not go far enough in their own countries.

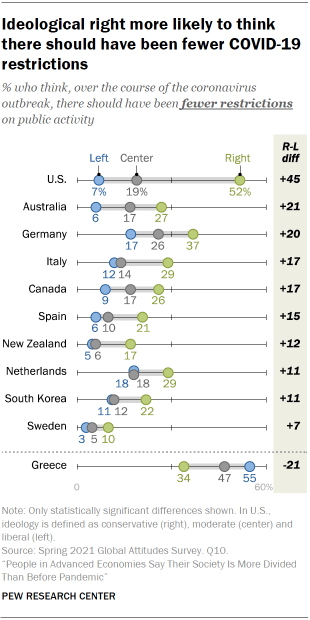

Ideologically, in most nations, those who identify on the right of the political spectrum are more likely than those on the left to support fewer restrictions to contain the virus.

Likewise, there are mixed assessments of the economic implications of the pandemic. A median of 46% say that their economy is recovering from the effects of the coronavirus outbreak in ways that show the strengths of the economic system. A nearly equal proportion instead believe that their economy failing to recover highlights weaknesses in their economy on the whole. This negative view is more prevalent among those who wanted fewer restrictions during the pandemic.

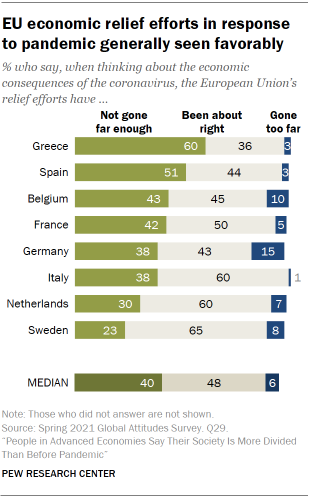

Specifically in Western Europe, the public is somewhat torn over whether economic relief from the European Union has gone far enough to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. Among eight EU member states, a median of 48% say the level of economic aid thus far is about right, while 40% say it has fallen short. Greeks and Spaniards voice the most concern that the EU’s relief efforts have not gone far enough.

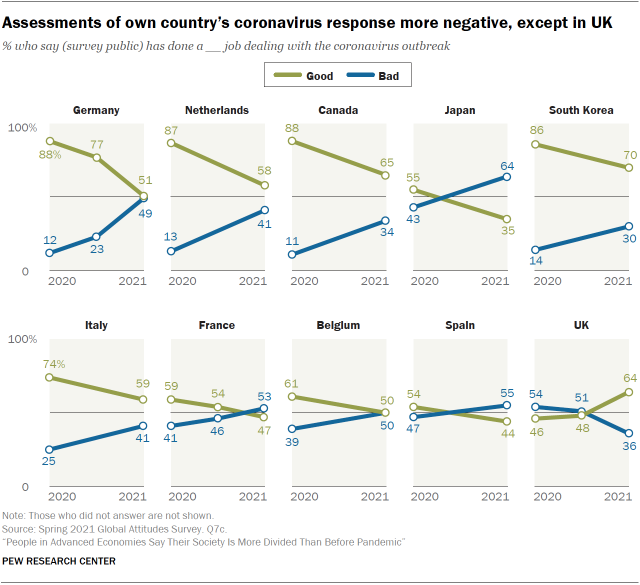

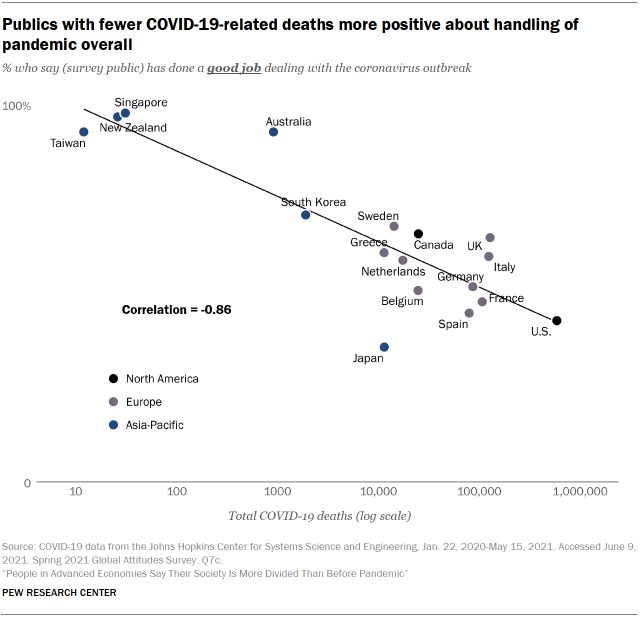

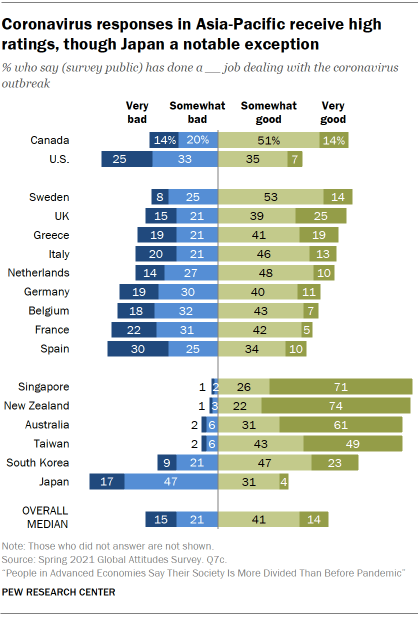

Most people across the 17 publics are relatively satisfied with the overall response to the pandemic where they live, though this has decreased over time in many places. A median of 60% think their own society has done a good job dealing with the coronavirus, and 40% think it has gone poorly. Many publics throughout the Asia-Pacific region, which have had much lower rates of coronavirus than elsewhere, are especially likely to say strategies have gone well. However, in several nations surveyed in both 2020 and 2021, the share with positive views of their own pandemic response has decreased in just a year. In Germany, for example, 88% of Germans in 2020 approved of their country’s response to the virus, while just 51% hold this opinion now, a drop of 37 percentage points. Decreases of at least 20 points also appear in the Netherlands, Canada and Japan.

There is a strong relationship between how positively one assesses their handling of the pandemic and the number of virus-related deaths in that society. For example, Singapore, New Zealand and Taiwan have each recorded fewer than 100 COVID-19 deaths (as of May 15, 2021). These publics also hold some of the most positive reviews of pandemic responses where they live, with more than nine-in-ten in each saying their society has done a good job dealing with the outbreak. On the other end of the spectrum, the U.S. had suffered more than half a million deaths in mid-May, and fewer than half of Americans say their country has done a good job handling the pandemic.

However, when thinking about future public health emergencies, majorities in every public surveyed express confidence that their health care system could handle such a situation.

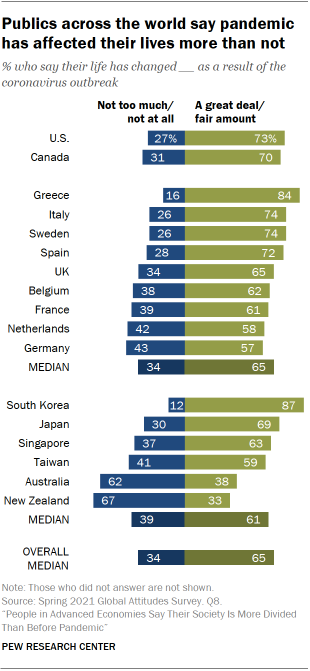

On the individual level, people across the 17 advanced economies surveyed now feel more of an impact in their day-to-day lives. A median of 65% say the pandemic has affected their everyday lives a great deal or fair amount, and majorities in each public hold this sentiment, with the exceptions of New Zealand and Australia. In 10 of the 13 countries surveyed in both 2020 and 2021, this figure has increased significantly over the course of the pandemic. Young people, in particular, are most likely to report that their life has changed as a direct result of the coronavirus.

These are among the findings of a new Pew Research Center survey conducted from Feb. 1 to May 26, 2021, among 18,850 adults in 17 advanced economies.

The coronavirus has left indelible marks on the world in myriad ways, and Pew Research Center’s international work has also felt these effects. Early in the pandemic, the Center confronted the impact of the outbreak and chose to suspend all face-to-face fieldwork in the name of safety for both interviewers and respondents. However, as we have continued to adapt to the new reality of polling in a pandemic, we also have to consider the constantly changing situation on the ground in places we survey and how that plays a role in shaping public opinion.

Fieldwork for this survey coincided with several major events related to national-level restrictions and vaccine distribution throughout the world. Numerous European countries instituted new lockdowns or lifted restrictions as the survey was fielded. Canada and each of the European Union countries surveyed paused use of the AstraZeneca vaccine for at least some of their population; the EU also sued the pharmaceutical company during this time. Several countries delayed the rollout for the Johnson & Johnson/Janssen vaccine.

Publics surveyed in the Asia-Pacific region were typically dealing with fewer or shorter restrictions due to less prevalence of the virus at that point. However, Japan declared a state of emergency for Tokyo and several prefectures during the survey, and since fieldwork ended the situation now looks more severe. The later part of fieldwork saw eyes turn toward a spiraling outbreak in India (a country not included in this survey) and international aid efforts to help contain the disease there. Taiwan and Singapore also experienced a sudden onset of new cases they had previously avoided, though these occurred largely after survey fieldwork concluded.

The U.S. survey was administered online and finished earlier than the rest of the surveys, with fieldwork running from Feb. 1-7, 2021. The country had administered more than 26 million vaccine doses but had not yet paused use of the Johnson & Johnson/Janssen vaccine. The third round of stimulus checks, part of a $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package, had not yet gone out to Americans.

This report offers a glimpse into how 17 publics thought about the pandemic at a particular point in time. Just as the pandemic has changed, sometimes quickly, over the course of the last year, so too could the public’s attitudes toward related topics such as national unity, restrictions and how their governments are handling the ever-fluid situation.

Feelings of social division increased since the start of the pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic has increased social divisions across many of the publics surveyed. A median of 61% across all 17 advanced economies say they are now more divided than before the outbreak, while 34% feel more united.

Sentiments are particularly negative in the U.S.: 88% of Americans say they are more divided than before the pandemic, the highest share to hold this view across all places polled. A majority of Canadians also say their country is more divided.

In Europe, majorities in seven of the nine nations surveyed say they are more divided than before the pandemic. Pessimistic views are particularly widespread in the Netherlands, Germany and Spain, where about eight-in-ten report more division. Only in Sweden and the UK do about four-in-ten believe they are more united than before the outbreak.

Views are considerably more varied across the Asia-Pacific publics surveyed. Majorities in Australia, Taiwan, New Zealand and Singapore say they are more united than before the coronavirus outbreak. On the other hand, majorities in Japan and South Korea feel more divided.

The view that societies are more divided than united has risen significantly in all but one of the 13 countries also included in a Pew Research Center summer 2020 survey.

The share who say they are now more divided than before the outbreak has increased by 20 percentage points or more in Canada (+32 points), Japan (+32), the Netherlands (+30), South Korea (+25) and Germany (+23).

At the same time, the percentage who say their public is now more united has plummeted. In Canada, for example, 66% said they were more united than before the pandemic in the summer of 2020. This spring, 36% say the same, a decline of 30 percentage points. Large declines are also observed in the Netherlands (-29 points), South Korea (-22), Germany (-21), Japan (-18) and Spain (-18).

Australians hold largely similar views of national unity as they did last summer. A majority in Australia say their country is more united, up just 5 points from 49% last summer, and views of countrywide division have remained largely the same.

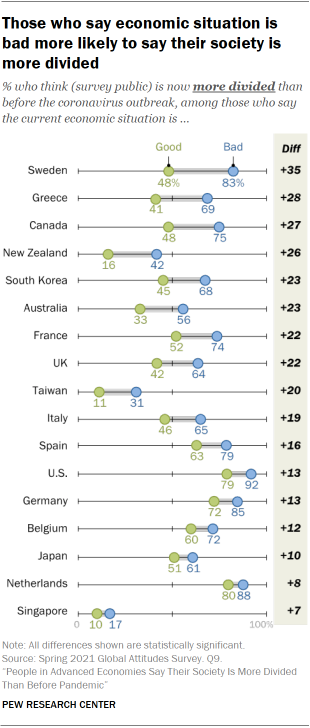

Those with negative views of the economy are more likely than those who think the economy is in good shape to say that their society is now more divided than before the coronavirus outbreak. This pattern is observed across every place included in the survey. For some, differences are substantial: In Sweden, for example, those who say their economic situation is bad are 35 percentage points more likely than those who say it is good to feel their public is more divided (83% vs. 48%, respectively).

Attitudes toward restrictions on public activity are linked to whether people feel division. In several of the advanced economies surveyed, those who say there should have been fewer restrictions are more likely to believe their public has grown more divided than before the coronavirus outbreak than those who felt there should have been more restrictions, or that restrictions were about right. In New Zealand, for example, 58% of those who say there should have been fewer restrictions on public activity also say their public is more divided, compared with 15% of those who say there should have been more restrictions.

Most in Asia-Pacific region say pandemic restrictions were about right, but Europeans are more divided

Overall, a median of 41% say restrictions on public activity where they live in response to the pandemic were about right. A sizable share – 37% – think more restrictions would have been appropriate. Just 18% say there should have been fewer restrictions on public activity over the course of the coronavirus outbreak. Greece is the only country polled where a plurality of adults (43%) favor fewer limitations.

In some publics, half or more think COVID-19 restrictions were too limited over the past year and a half. For example, 62% of Japanese adults think there should have been more restrictions, as do 56% of American adults. (Japan and the U.S. also received some of the worst ratings for their coronavirus responses from their own publics.)

Still, many publics think that their governments implemented the right restrictions on public activity. New Zealand – which has won praise for its coronavirus response and has recorded only 26 coronavirus-related deaths at the time of writing – has the highest share who say restrictions were about right at 80%. Majorities in Taiwan, Australia and Singapore also say coronavirus restrictions were about right.

Support for right-wing populist parties is also tied to views of coronavirus restrictions. In the Netherlands, 42% of respondents with favorable views of the right-wing Forum for Democracy (FvD) party say there should have been fewer restrictions on public activity during the coronavirus outbreak. Just 17% of those with unfavorable views of FvD share that view. Similar splits appear between supporters and nonsupporters of Alternative for Germany, Lega and Forza Italia in Italy, Vox in Spain, Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, Sweden Democrats, Greek Solution and Reform UK.

In most publics surveyed, those on the ideological right are significantly more likely than those on the left to say there should have been fewer restrictions. In the U.S., 52% of conservatives say there should have been fewer restrictions; just 7% of liberals say the same. Greece is the only public surveyed where those on the left are more likely than those on the right to say there should have been fewer restrictions (55% and 34%, respectively).

Many in U.S., Europe and Japan say the pandemic has revealed weaknesses of their economic system

The coronavirus outbreak has wreaked havoc on the global economy, reversing years of progress in the fight against global poverty and pushing millions out of the global middle class. But the economic effects of the pandemic have not been uniform, and opinions vary widely regarding how publics assess their economic system’s durability.

In Europe, views are largely pessimistic, with a median of 58% saying that their economy is failing to recover from the effects of the coronavirus outbreak in ways that show the weaknesses of their economic system. (The EU has recorded two straight quarters of negative gross domestic product growth after a sharp rebound in the third quarter of 2020.) Opinions are particularly negative in Spain and Italy, with roughly three-quarters or more holding this opinion.

Sweden, which has refused to implement wide-ranging lockdown measures, is an exception in Europe, with three-quarters saying that the economy is recovering in ways that show the strengths of its economic system. Dutch adults are also optimistic, and opinions in the UK and Germany are split.

Opinions in the Asia-Pacific region are more positive, with majorities in nearly all publics surveyed saying their economy is recovering in ways that show the strengths of their system. Again, Japanese opinions are an exception in the region, with 77% of adults saying their economy is failing to recover from the effects of the coronavirus outbreak. Japan’s economy shrank an annualized 5.1% in the first quarter of 2021 after an 11.6% surge in growth in the previous quarter.

Attitudes about how the economy is recovering are very closely tied to opinions about the appropriateness of coronavirus-related restrictions. In most publics surveyed, people who think there should have been fewer COVID-19 restrictions are more likely than those who think restrictions were about right to be pessimistic about their economy’s recovery.

Those who say their current economic situation is bad are far more likely to say their economy is failing to recover from the effects of the coronavirus outbreak in every public surveyed.

EU economic response to pandemic gets mixed reviews

While majorities or pluralities in half of the eight European Union countries polled say EU economic relief efforts have been about right, large shares in several countries say efforts have not gone far enough. A median of 48% across these countries say efforts have been about right, while a median of 40% believe relief efforts have fallen short. A median of just 6% say efforts have gone too far.

Satisfaction with the bloc’s economic relief efforts – which included a 750 billion euro ($858 billion) stimulus package negotiated in July 2020 – is highest in Sweden, where 65% agree these efforts have been appropriate. Six-in-ten in Italy and Netherlands say the same.

However, satisfaction is not widespread across the EU member countries included in the survey, as member nation governments continue to decide how best to spend stimulus money. In Greece, for example, 60% say economic relief efforts have not gone far enough, the highest share who express such dissatisfaction. While all EU countries experienced economic hardship as a result of the pandemic, Greece was particularly impacted. In a fall 2020 economic forecast from the European Commission, Greek GDP was projected to shrink by roughly 9%, one of the largest contractions projected across all EU member states. Publics in Belgium and Spain are roughly split between shares who are say the EU economic response has been adequate and those say it has not gone far enough.

Views of the current economic situation also impact satisfaction with EU economic relief. In all EU countries polled, those who say the economic situation is bad are more likely than those who say the situation is good to believe the EU has not gone far enough in its relief efforts. In Greece, for example, 68% of those who say the economic situation is bad say EU relief efforts have not gone far enough, compared with 39% of Greeks who say the economic situation is good.

Across several member countries, supporters of right-wing populist parties are more likely than nonsupporters to say EU relief efforts have not gone far enough. For example, in Italy, Forza Italia supporters are 18 percentage points more likely than nonsupporters to believe EU economic relief has fallen short (50% vs. 32%, respectively).

Coronavirus responses receive mixed reviews from publics, lower ratings than in summer 2020

In contrast to how the U.S. and China were rated around the world for their responses to the coronavirus outbreak, adults largely give high ratings to the coronavirus response where they live, especially in the Asia-Pacific publics surveyed.

For instance, nearly all adults in Singapore and New Zealand say their own countries have done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak (97% and 96%, respectively), including more than seven-in-ten who say the response has been very good. About nine-in-ten in Australia and Taiwan and seven-in-ten in South Korea rate their responses to the coronavirus outbreak positively.

Japan is the exception in the Asia-Pacific region, with 64% saying Japan has done a bad job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak. About half or more in the U.S., Spain, France, Belgium and Germany also rate their pandemic responses negatively.

In many countries, ratings of coronavirus responses have slipped significantly since summer 2020. This is particularly true in Germany, where the share of Germans saying their country has done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak has fallen 37 percentage points from 88% in summer 2020 to 51% in spring 2021. Positive ratings have also fallen by double digits in the Netherlands, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Italy, France, Belgium and Spain.

The UK, which has implemented one of the quickest and most successful vaccine campaigns worldwide, is the only place where ratings have improved. In summer 2020, 46% of Britons rated their national response positively; today, 64% do.

Economic confidence relates to how people assess their nation’s handling of the pandemic. In every public surveyed, those who think the current economic situation is good are more likely to say their society’s response to COVID-19 has been good.

The converse is also true: Those who think the current economic situation is bad also tend to rate their national response negatively. This gap is widest in Greece, where 92% of those who say the current economic situation is good and 48% of those who say the current economic situation is bad rate the Greek coronavirus response positively, a difference of 44 percentage points.

Many say their lives have been impacted by the coronavirus pandemic

Over a year after the coronavirus outbreak first emerged across the world, more people in the 17 publics surveyed feel their lives have changed as a result of the pandemic than not. A median of 65% say their lives have changed a great deal or a fair amount as a result of the coronavirus outbreak, ranging from 33% in New Zealand to 87% in South Korea.

About seven-in-ten in both the U.S. and Canada believe the pandemic has changed their lives at least a fair amount, while roughly three-in-ten say their lives have not changed much or at all. Across the nine European publics surveyed, a median of 65% say their lives have changed. Majorities across these nine publics hold this view, including more than eight-in-ten in Greece.

Responses to the outbreak’s impact on people’s lives are more varied across the six Asia-Pacific publics included in the survey. Fewer than four-in-ten in both Australia and New Zealand believe the pandemic has changed their lives, yet majorities in Taiwan, Singapore, Japan and South Korea say their lives have been impacted.

Two countries stand out as reporting relatively little change as a result of the pandemic: Australia and New Zealand. Majorities in each say their lives have not changed much or at all. Both nations have remained relatively sheltered from the worst of the pandemic by strict lockdowns, widespread testing, contact tracing and public compliance with containment measures, as well as by geography. During fieldwork, Australia and New Zealand opened their borders to those from the other nation, allowing visitors from each country to travel without a quarantine period.

The perception that life hasn’t changed much during the pandemic drops off steeply outside of Australia and New Zealand. The next largest share to hold this view are Germans (43%).

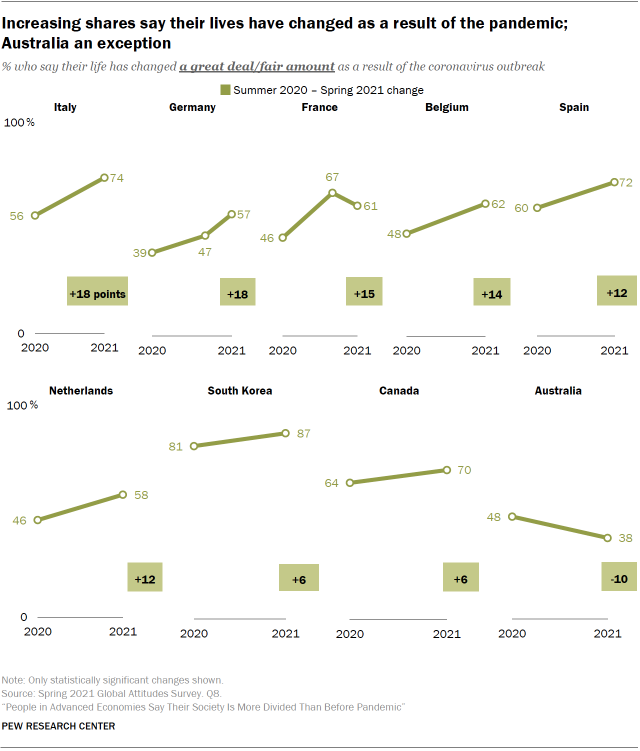

Among most of the 12 countries surveyed in both the summer of 2020 and this spring, more now say their lives have changed a great deal or fair amount than say the opposite. A median of 58% across these 12 countries said last summer that their lives had changed at least a fair amount, while a median of 67% across the same group of countries say the same this year.

The share who say their lives have changed as a result of the coronavirus outbreak has increased significantly in eight of the 12 countries included on both surveys (Japan, Sweden and the UK are exceptions) with double-digit increases in Italy (+18 percentage points), Germany (+18), France (+15), Belgium (+14), the Netherlands (+12) and Spain (+12).

The only place in which the share who believe their lives have changed has declined significantly is Australia, where 38% say their lives have changed at least a fair amount this year, down 10 percentage points from 48% who said the same in the summer of 2020.

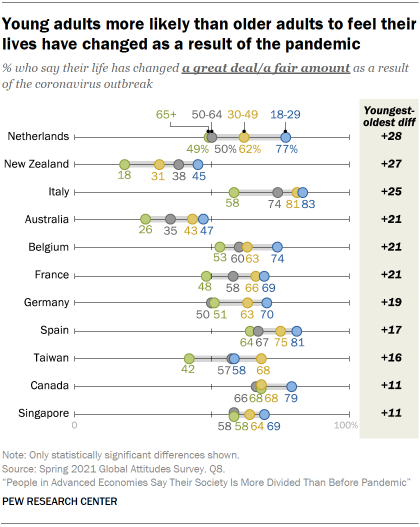

While many say their lives have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, young people are particularly likely to express this sentiment. Young adults have faced unique challenges over the past year, including disruptions to school and early career opportunities. Adults ages 18 to 29 across many publics surveyed are more likely than those 65 or older to say their lives have changed as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. In the Netherlands, for example, younger adults are 28 percentage points more likely than their older counterparts to say their lives have changed as a result of the virus. Similarly, large differences between younger and older adults are present in New Zealand (+27 points), Italy (+25), Australia (+21), Belgium (+21) and France (+21).

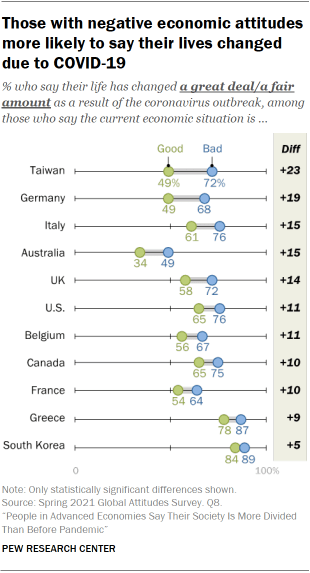

Attitudes toward the economy are linked to perceptions of change due to the pandemic in most advanced economies: Those who say the current economic situation in their country is bad are more likely to say their lives have changed. In Taiwan, for example, 72% of those who say the current economic situation is bad believe their lives have changed as a result of the coronavirus outbreak, compared with 49% who say the economic situation is good. Double-digit differences were found in eight other advanced economies.

Optimism that health care systems can handle future emergencies

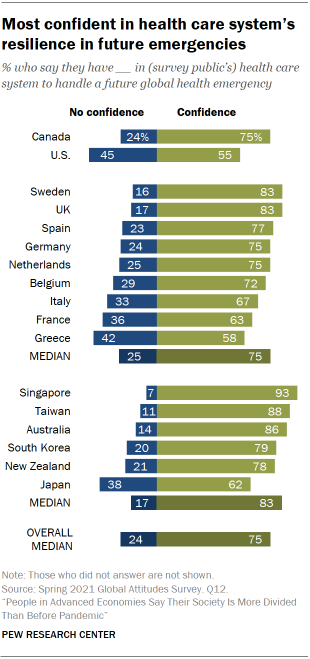

Majorities in all 17 publics included in this survey express confidence in their health care system to handle a future global health emergency. Overall, a median of 75% hold this opinion.

Those in the Asia-Pacific region believe in their health systems by a wide margin, with a median of 83% confident the system could handle a future global public health emergency. About eight-in-ten or more say this in Singapore, Taiwan, Australia, South Korea and New Zealand. Notably, 60% of Singaporeans express a great deal of confidence, as do roughly four-in-ten in Australia and Taiwan.

Europeans, too, have positive opinions about their national health care system’s ability to cope with a hypothetical public health emergency. A median of 75% across the nine European countries surveyed voice confidence, while 25% do not. Those in Sweden and the UK have the highest levels of confidence among the European countries surveyed. And about four-in-ten in Spain, the UK and Germany report a great deal of confidence in their national health systems.

Canadians, too, hold high opinions of their country’s health care system in the face of a future global health emergency. That is not the case, however, in the U.S., where the lowest share among the 17 publics voices confidence. This may relate to the nature of the American health care system; it is the only advanced economy in the survey (and in the world) without universal health insurance coverage and often ranks toward the bottom in comparative analyses of health systems in high-income nations.