Americans are especially likely to say politicians are corrupt

This report examines people’s trust in government and satisfaction with democracy, as well as their attitudes toward elected officials and political reform.

For this analysis, we use data from nationally representative telephone surveys of 4,069 adults from Nov. 10 to Dec. 23, 2020, in the U.S., France, Germany and the UK. In addition to the survey, Pew Research Center conducted focus groups from Aug. 19 to Nov. 20, 2019, in cities across the U.S. and UK (see here for more information about how the groups were conducted). We draw upon these discussions in this report.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

As they continue to struggle with a public health crisis and ongoing economic challenges, many people in the United States and Western Europe are also frustrated with politics.

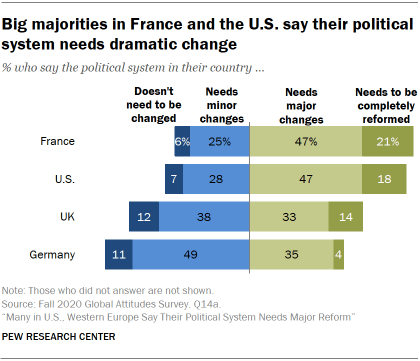

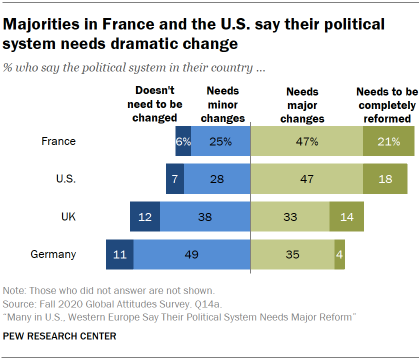

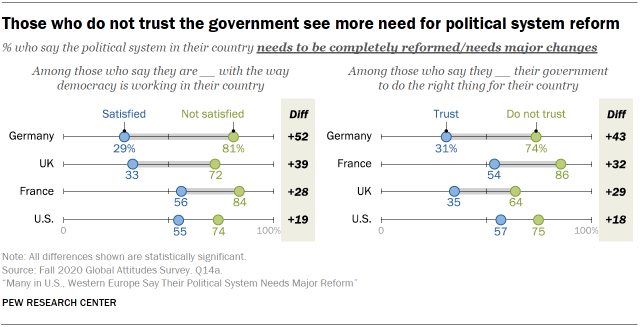

A four-nation Pew Research Center survey conducted in November and December of 2020 finds that roughly two-thirds of adults in France and the U.S., as well as about half in the United Kingdom, believe their political system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed. Calls for significant reform are less common in Germany, where about four-in-ten express this view.

Of course, there are important differences across these countries’ political systems. But the four nations also share some important democratic principles, and all have recently experienced political upheaval in different ways, as rising populist leaders and movements and emerging new forces across the ideological spectrum have challenged traditional parties and leaders.

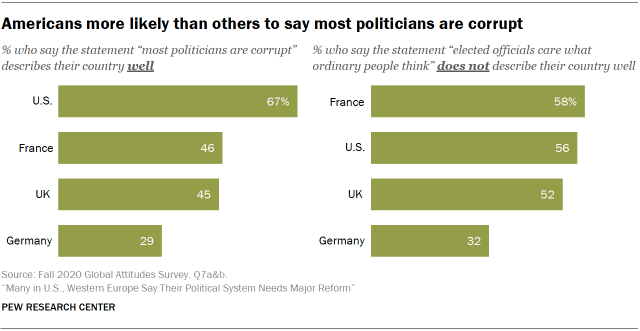

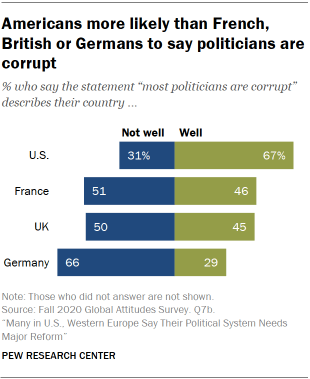

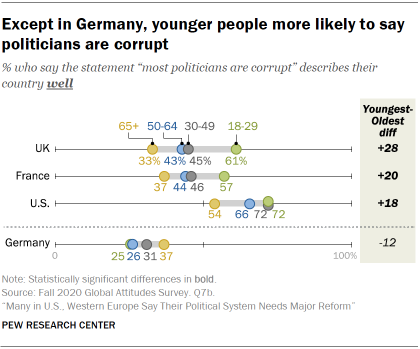

Some of the frustrations people feel about their political systems are tied to their opinions about political elites. In the U.S., concerns about political corruption are especially widespread, with two-in-three Americans agreeing that the phrase “most politicians are corrupt” describes their country well. Nearly half say the same in France and the UK. Young people, in particular, generally tend to see politicians as corrupt. And those who say most politicians are corrupt are much more likely to think their political systems need serious reform.

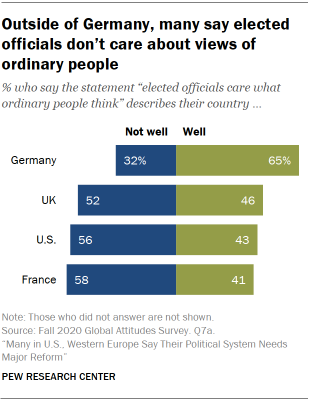

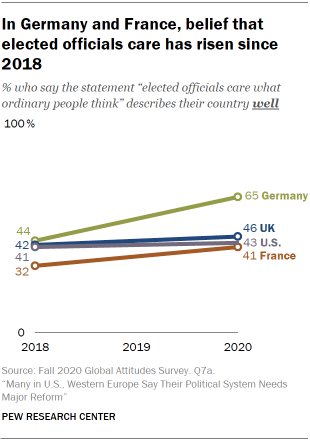

A belief that politicians are out of touch is also common. In France, the U.S. and the UK, roughly half or more say elected officials do not care what ordinary people think. Still, in both France and Germany, the share of the public who believe elected officials do care has increased since 2018.

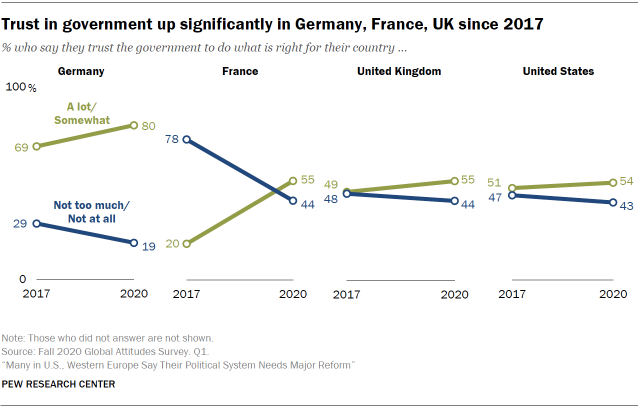

Since 2017, the French and German publics have also become more trusting of government. In France, just 20% said they trusted the government to do what is right for the country in 2017, compared with 55% in the new survey. Trust is especially high among supporters of President Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche party, but it has risen across the partisan spectrum. Similarly, trust is up among supporters of parties on the right, left and center in Germany.

Trust in government has also increased slightly in the UK, although while it has risen among supporters of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party, is has actually declined among those who identify with the opposition Labour Party.

How Pew Research Center measures public trust in government, globally and domestically

For several years, Pew Research Center has been committed to researching issues of trust, facts and democracy. And for decades, the Center has studied Americans’ attitudes about federal, state and local government in the United States.

In this survey, the Center compares the attitudes of the publics in four nations – the U.S., France, the UK and Germany – toward democracy and their countries’ political systems. The survey also includes a measure of trust in the four countries’ national governments: How much do respondents trust the government “to do what is right for their country?”

This is different from the question that has been asked for more than six decades by Pew Research Center and other survey organizations in the U.S.: “How much of the time do you think you can trust the government in Washington to do what is right?

In the United States, the measures yield very different results: Last August, just 20% of the public said they trusted the government in Washington to do what is right “always” or “most of the time.” Americans’ trust in the federal government has been mired at that low level for longer than a decade.

In the four-nation survey, which was conducted in the U.S. in November – after Joe Biden had been declared the winner of the presidential election, but when large shares of Donald Trump’s supporters expressed skepticism about the result and the voting process – 54% of Americans said they trust the government a lot or somewhat to do what is right for the country. This is little changed from 51% who said this in 2017.

The four-nation survey provides a valuable comparative examination of views of government, the political system and the state of democracy. In the coming months, the Center will update its long-standing measures of Americans’ trust in their government, as well as attitudes on the scope and size of government.

In the U.S., the overall level of trust in the government has remained largely unchanged since 2017, but who trusts the government shifted substantially. In 2017, only months after Donald Trump was elected president, Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party were more likely to trust the government than Democrats and those who lean Democratic. In the current survey, fielded in November and December 2020 – after major media outlets had called the election for now-President Joe Biden – Democrats express higher levels of trust.

In the U.S., the period when the survey was conducted – Nov. 7 to Dec. 10, 2020 – was particularly tumultuous politically. Although now-President Joe Biden was declared the winner of the election by the Associated Press and other media organizations as the survey began, and was recognized as the president-elect by key international leaders, prominent Republicans refused to acknowledge his victory. Dozens of lawsuits also attempted to challenge the results, largely on the basis of voter fraud. During this period, a separate Pew Research Center survey found that Trump and Biden voters were deeply divided over nearly all aspects of the election and voting process, including whether their own votes were counted accurately and whether they wanted the Trump campaign to continue its legal challenges of the results.

As this survey concluded in early December, most lawsuits had been dismissed and electoral results had been certified in most states, leaving few legal avenues available to contest the election. However, Congress had not yet formally certified the electoral college results – a process which ultimately took place on Jan. 6, 2021, the same day violent protests by a pro-Trump mob also erupted at the U.S. Capitol.

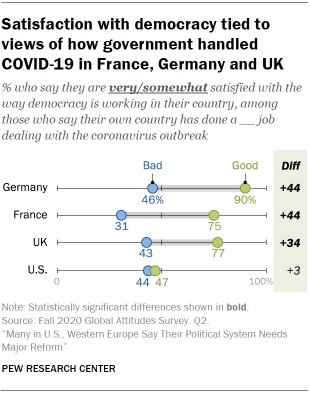

In France, Germany and the UK, trust in government tends to be higher among those who think their country has done a good job of handling the coronavirus pandemic. This is particularly true in France, where 80% of those who say the country is handling the outbreak well trust the government, compared with only 27% of those who say the country is doing a poor job.

Trust is also linked to views about the economy. People who think the national economy is currently in good shape express higher levels of trust in government, as do those who believe they have a good chance to improve their own standard of living.

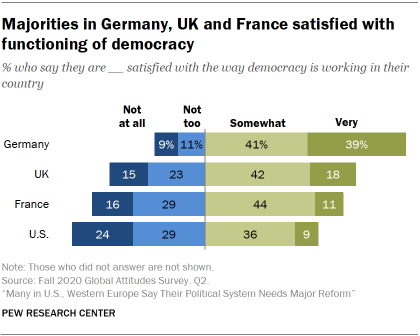

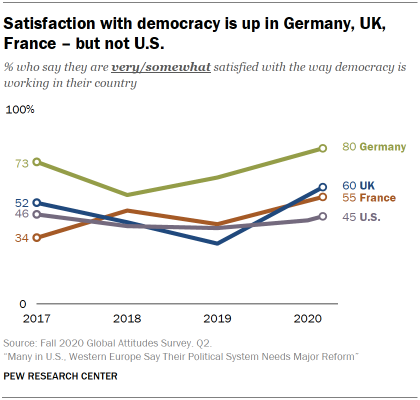

While more than half of Americans say they generally trust the government to do what is right, fewer than half (45%) are satisfied with the way democracy is working in their country. (The survey took place before the violent storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 by a mob of Trump’s supporters.) In contrast, majorities in France (55%) and the UK (60%), as well as eight-in-ten Germans, say they are satisfied with how democracy is functioning.

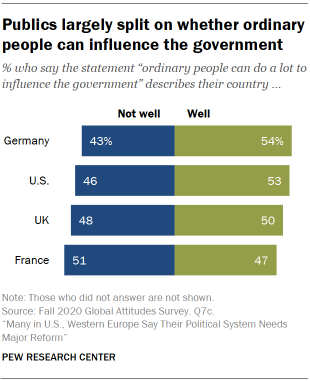

These four publics are divided over how much impact ordinary people can have on government: 54% of Germans, 53% of Americans, 50% of Britons and 47% of the French say the statement “ordinary people can do a lot to influence the government” describes their country well.

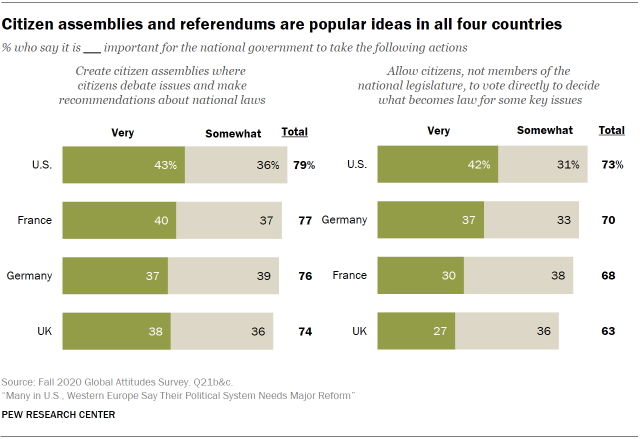

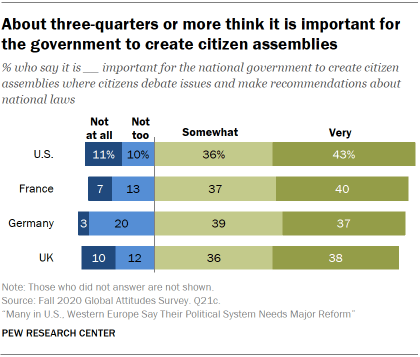

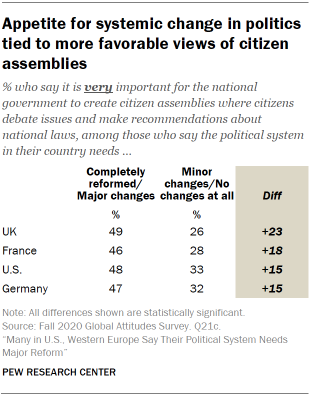

In all four countries, there is considerable interest in political reforms that would potentially allow ordinary citizens to have more power over policymaking. Citizen assemblies, or forums where citizens chosen at random debate issues of national importance and make recommendations about what should be done, are overwhelmingly popular. Around three-quarters or more in each country say it is very or somewhat important for the national government to create citizen assemblies. About four-in-ten say it’s very important. Such processes are in use nationally in France and the UK to debate climate change policy, and they have become increasingly common in nations around the world in recent years.

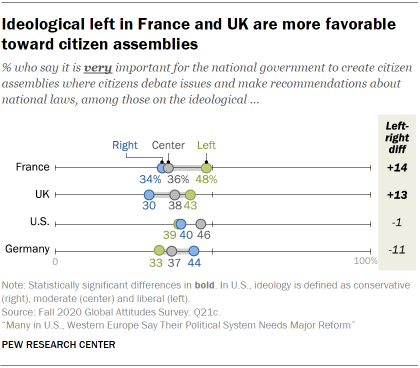

Citizen assemblies are popular across the ideological spectrum but are especially so among people who place themselves on the political left.1 Those who think their political system needs significant reform are also particularly likely to say it is important to create citizen assemblies.

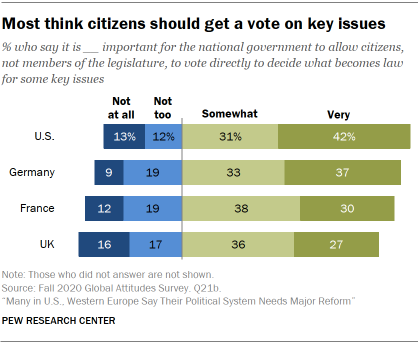

There are also high levels of support for allowing citizens to vote directly to decide what becomes law for some key issues. About seven-in-ten in the U.S., Germany and France say it is important, in line with previous findings about support for direct democracy. In the UK, where crucial issues such as Scottish independence and Brexit were decided by referendum, support is somewhat lower – 63% say it is important for the government to use referendums to decide some key issues, and just 27% rate this as very important.

These are among the findings of a new Pew Research Center survey conducted from Nov. 10 to Dec. 23, 2020, among 4,069 adults in the France, Germany, the UK and the U.S. This report also includes findings from 26 focus groups conducted in 2019 in the U.S. and UK.

Pew Research Center conducted 26 focus groups from Aug. 19 to Nov. 20, 2019, in cities across the U.S. and UK (for details on how the groups were stratified, see the methodology). All groups followed a discussion guide designed by the Center and were asked questions about their local communities, national identities and globalization by a trained moderator.

This report draws from those discussions, and we have included quotations which have been lightly edited for grammar and clarity. Quotations are chosen to provide context for the survey findings and do not necessarily represent the majority opinion in any particular group or country.

Across the four countries surveyed, more trust the government than not

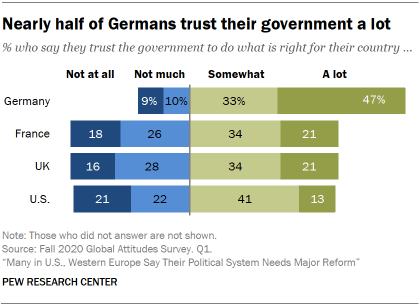

Half of adults or more trust the national government to do what is right in each of the four countries surveyed. But, whereas only a slim majority trust the government in the United States (54%), France (55%) and the United Kingdom (55%), 80% in Germany express this view. And, in Germany, 47% say they trust the national government a lot – more than twice as many as say the same in any of the other surveyed countries and more than three times as many as in the U.S., where only 13% have a lot of faith in the government.

In the U.S., trust in the government has remained largely unchanged since the question was last posed in 2017. But who trusts the government shifted notably over this period. In 2017, when Donald Trump was the newly inaugurated president, Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party were more likely to trust the government than Democrats and leaners toward that party (66% vs. 42%, respectively). In the most recent survey, fielded in November 2020 after the election was called for now President Joe Biden, Democrats trust the government at higher rates than Republicans, 59% vs. 49%.

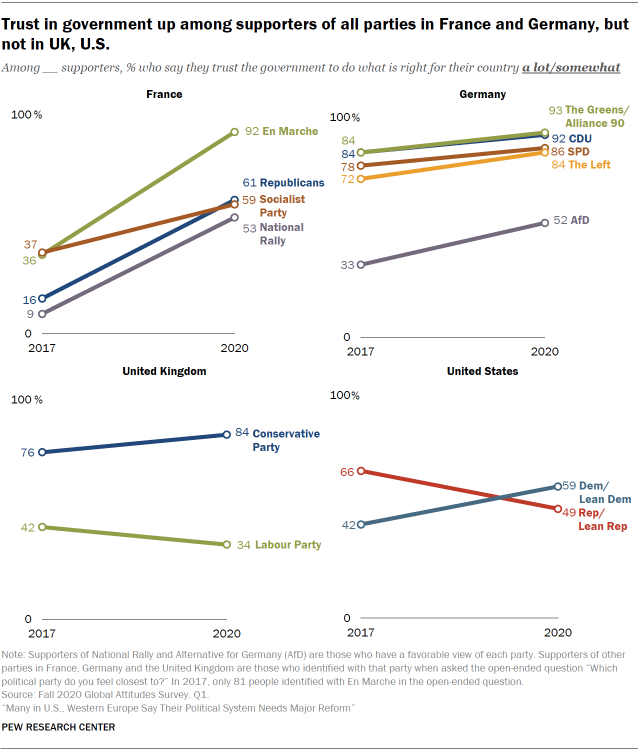

Trust in the government has increased in each of the three European countries surveyed since 2017, the largest change being in France (55% today, up from 20%). The 2017 French survey was fielded in the month prior to the first round of the national elections – a particularly contentious election in which nontraditional parties, including the now-governing En Marche, were vying for leadership.2 Trust has grown most precipitously among En Marche supporters: Today, 92% trust the government, compared with 37% who said the same before the 2017 election that brought Emmanuel Macron to power. Supporters of the Republicans (LR) and the Socialist Party (PS) – two parties that had long governed in France prior to 2017 – also have more trust in the government now. And, while only around half of those with a favorable view of the right-wing populist National Rally trust the government (53%), trust among this group has gone up 44 percentage points since 2017.

In Germany, trust in the government is up 11 percentage points since 2017, and the share who trust the government a lot has nearly doubled during this same period. But, while supporters of the ruling CDU are among the most trusting of the government (92%), trust has increased comparably since 2017 among most of the major parties. And, while those who have a favorable view of Alternative for Germany (AfD) tend to be much less trusting than those who have an unfavorable view of the party (52% vs. 85%), even this group is more trusting of the government now than in 2017, when only 33% trusted the government.3

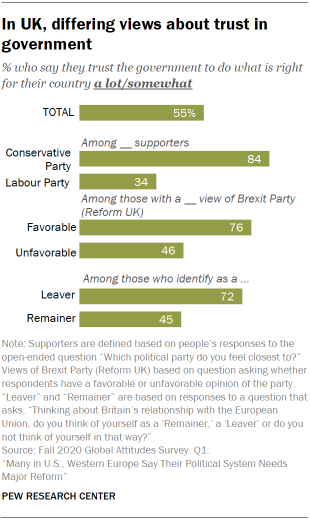

In the UK, the share who trust the government a lot has risen 7 points since 2017 (to 21%), and overall trust has increased 6 points. For supporters of the Conservative Party – which was governing in 2017 but had a change of prime minister in 2019 – trust in the government has gone up from 76% to 84%. On the other hand, Labour Party supporters are less likely to trust the government now than they were in 2017 (34%, down from 42%). Trust is significantly higher among those who identify as Leavers (72%) than those who identify as Remainers (45%), as well as among those who have a favorable view of the right-wing populist Brexit Party, now called Reform UK (76%) compared with those who have an unfavorable view of the party (46%).4

Across all four of the countries surveyed, trust in the government is higher among those who say the economy is in good shape and those who say they have adequate opportunities to improve their own standard of living. For example, in the UK, those who say their current economic situation is good are about two times as likely to say they trust the government as those who say it’s bad.

In France, Germany and the UK, those who think their country is doing well handling COVID-19 are much more likely to trust the government than those who think their country is handling the pandemic poorly. The difference is largest in France, where 80% of those who think the country is doing well handling the outbreak trust the government, compared with only 27% of those who think the country is not doing a good job.

Trust is higher among people who believe elected officials care what ordinary people think. Also, those with at least a university degree and those with higher incomes are more likely to trust the government in France and Germany, though not in the U.S. or UK.

Democratic satisfaction lower in U.S. than European countries surveyed

Satisfaction with democracy varies widely across the four countries surveyed. In the U.S., only 45% of people say they are satisfied with the way democracy is working (the survey in the U.S. took place Nov. 10 to Dec. 7, 2020, which was before the violent storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 by a mob of President Trump’s supporters). In contrast, in each of the three European countries surveyed, a majority holds this view: 55% in France, 60% in the UK and 80% in Germany. And, in Germany, around four-in-ten are very satisfied (39%). No more than one-in-five in the other three countries surveyed reach this level of satisfaction.

Across all three European countries surveyed, satisfaction with democracy has increased substantially: up 14 points in France, 15 points in Germany and 29 points in the UK between 2019 and 2020. In contrast, in the U.S., the percentage of people who say they are satisfied with democracy has remained relatively consistent in recent years.

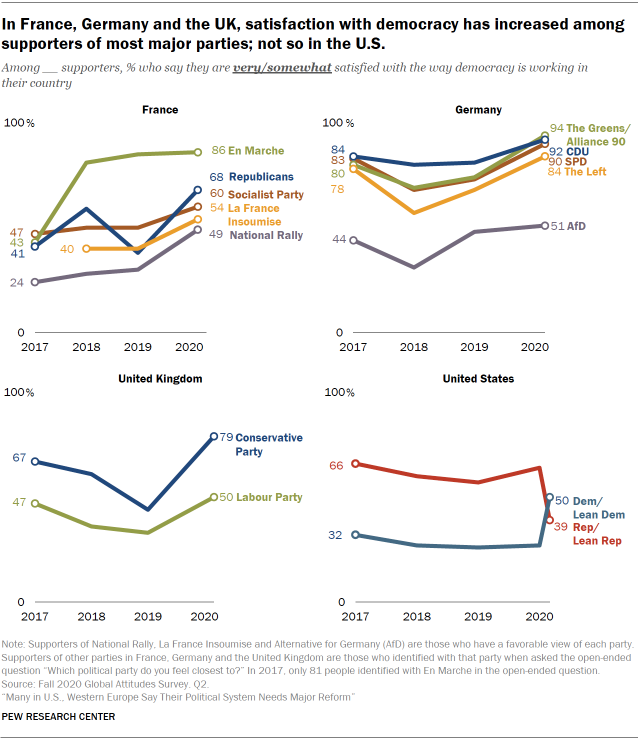

But, in the U.S., who is satisfied has changed substantially over the past year. Between 2017 and 2019, Republicans were more than twice as satisfied with democracy as were Democrats. In 2019, for example, 57% of Republicans and 26% of Democrats said they were satisfied. But, in 2020, after Biden’s election, this relationship inverted, and today, 50% of Democrats are satisfied with democracy while only 39% of Republicans say the same.

In each of the European countries surveyed, supporters of the party or parties that are currently in government tend to be among the most satisfied with democracy. While En Marche supporters are the most approving of the way democracy is working in France, their opinions have shifted little since a 2018 survey, which was the first Pew Research Center poll in France following their party’s electoral victory. Rather, much of the 14-point increase in democratic satisfaction between 2019 and 2020 in France has come from supporters of other parties. For example, 60% of the supporters of the Socialist Party now report satisfaction with democracy, up from 50% in 2019. The growth among Republicans is even larger, going from 40% in 2019 to 68% in 2020. Satisfaction is even up among those who hold favorable views of the right-wing populist party National Rally (49% in 2020, up from 30% in 2019) and the left-leaning populist party La France Insoumise (54% in 2020, up from 40% in 2019).

The increase in democratic satisfaction is evident among supporters of most large German political parties in the country. For example, supporters of SPD (up 17 points), the Greens/Alliance 90 (16 points) and CDU (11 points) as well as those with a favorable view of Die Linke (16 points) all are more satisfied with democracy now than in 2019. But those with a favorable view of the right-wing AfD have not changed over the past year and continue to have relatively low democratic satisfaction (51%).

In the UK, supporters of the Conservative Party (79%) are more satisfied with democracy than Labour Party (50%) supporters. But this comes as partisans in both camps are more satisfied than they were in 2019, with increases of 35 and 17 points, respectively. Those who identify as Leavers and Remainers are equally satisfied with how democracy is working in their country.

Leavers and Remainers both saw Brexit as a failure of democracy in focus groups

Focus groups conducted in August 2019 in the UK were dominated by discussions of Brexit. At the time, around three years had passed since voters had approved a referendum to leave the European Union. Boris Johnson had just taken over as prime minster from Theresa May, and invocation of Article 50 – the start of formal withdrawal – had been delayed until at least October, meaning the UK was still in the EU and still consumed by debates about Brexit. Both Leavers and Remainers saw the aftermath of the referendum as a gross failure of democracy. Although Brexit was not an explicit topic for guiding focus group discussion, it came up in several groups as something that made people feel ashamed to be British.

For Leavers, complaints centered around frustrations that, despite their vote to leave, the country had made no forward progress on the issue, thus “highlight[ing] clearly how little our opinion matters.” Leavers bemoaned calls for a second referendum that were percolating at the time, arguing that overturning the will of the people, which they thought had been fully expressed in the 2016 vote, would be a miscarriage of democracy.

For Remainers, frustrations often hinged on the process. People felt that misinformation was rampant in advance of the 2016 vote, and many who voted to leave may not have done so had they understood the implications of their vote. Others highlighted how it would have made more sense to negotiate a deal and put that to the people in a referendum, rather than voting first on whether to leave when there was no clear plan on how to execute it. Remainers also noted that Brexit has “diverted all other issues,” “distracting” the government away from “running the country,” which one participant even blamed for an increase in crime.

Despite wanting wildly different outcomes with regard to Brexit, what united Leavers and Remainers were a few core complaints and their general dissatisfaction with their politicians and the political process. Both Leavers and Remainers lamented how much time Brexit was taking and suggested just “getting on with it.” People highlighted how it was difficult to plan for the future with such a major decision in limbo. Some emphasized how the whole thing made Britain look weak, the politicians seem ineffective, and the country was becoming a global “laughing stock.”

There are few age or gender differences across these countries when it comes to satisfaction with democracy. But those who have completed at least a university degree tend to be more satisfied with democracy than those who have completed only some university schooling or less.

Across all four countries surveyed, people who think the economy is in good shape are significantly more content with the functioning of their political system than those who think the economy is in poor shape. In France, for example, those who think the economy is in good shape are more than twice as likely to be satisfied with democracy (70% vs. 33%). Similarly, those who think they have opportunities to improve their own standard of living are also more satisfied with democracy.

Those who think elected officials care what ordinary people think are also more likely to be satisfied with democracy.

In France, Germany and the UK, people who think their country has done well handling COVID-19 are also around twice as likely to be satisfied with democracy as those who think their country has handled the pandemic poorly. But, in the U.S., those who think the country has done well and those who think it has done poorly when dealing with the global health crisis are equally satisfied with democracy.

Outside of Germany, many see need for major changes to their political systems

Across the four countries surveyed, few say they live in a political system that does not need to be changed at all: 6% in France, 7% in the U.S., 11% in Germany and 12% in the UK. But what degree of change they seek – minor, major or complete reformation – varies.

In both France and the U.S., a majority say dramatic change is needed, with a plurality in each country saying the system requires major changes (47% in each country). In the UK, fewer seek substantial changes (14% complete reform, 33% major changes), and the largest share of people report the system needs minor changes (38%). Only in Germany do substantially fewer than half seek serious changes.

In the U.S., Democrats and independents who lean toward the party tend to be slightly more supportive of major systemic overhaul than Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party – 70% vs. 58%, respectively. This is consistent with results of other recent surveys showing that Democrats are more supportive of reforms like moving away from the electoral college or doing everything possible to make it easier for every citizen to vote. Democrats are also less likely than Republicans to describe America as a country where people are free to peacefully protest or where the rights and freedoms of all people are respected.

Supporters of the party currently in power in France – En Marche – are slightly less likely to support major systemic overhauls (51%) than are supporters of the two major traditional political parties: the Republicans (59%) and the Socialist Party (70%). But those with favorable views of the populist right-wing National Rally and left-wing La France Insoumise are no more likely to call for major changes or complete reform to the French political system than are those with unfavorable views of those parties.

In the UK, support for at least major changes is higher among Labour Party supporters (57%) than among Conservative Party supporters (29%). Those who identify as Remainers are also more supportive of significant changes to the political system than those who identify as Leavers. Similarly, those who have an unfavorable view of the right-wing Brexit Party (Reform UK) tend to be more likely to want systemic reforms than those who have a favorable view of the party (56% vs. 30%, respectively).

In Germany, where the overall desire for change is relatively low, there are few differences along partisan lines.

Across all four countries surveyed, those who think most politicians in their country are corrupt are more likely to favor systemic reforms. For example, in the UK, 60% of those who say “most politicians are corrupt” describes their country well think the system needs significant changes, compared with 39% who say it does not describe the country well. Those who are less satisfied with the way democracy is working and less trusting of the government are more likely to call for significant changes. On the other hand, those who think elected officials care what ordinary people think are less likely to think large-scale reforms are required.

Views of how well COVID-19 has been handled also play a role: People who think their government has done a poor job dealing with the pandemic are also more likely to call for major reforms. In Germany, for example, 70% of those who think the government has done a poor job think the system needs complete or major reforms, compared with just 29% of those who think the government has dealt with the pandemic well.

Those who believe their country is doing poorly economically are also more likely to call for substantial reforms to the political system. The same is true of those who say they lack opportunities to improve their standard of living. But opinions don’t differ across age groups in any of these countries, with younger and older people equally likely to support calls for reform.

Outside of Germany, there are no significant differences across income groups on this question (in Germany, the less affluent are more likely to support changes). In Germany, the U.S. and France, those with secondary degrees or less schooling are also more likely to call for major political system reform than those with more education.

Elected officials seen as out of touch in U.S., France and UK

Nearly two-thirds of Germans (65%) say the statement “elected officials care what ordinary people think” describes their country well. However, fewer than half of those surveyed in France, the U.S. and the UK express this opinion.

The share of Germans who say elected officials care what ordinary people think has risen precipitously since 2018, when only 44% held this view. In France, too, the share saying elected officials care has risen 9 points (from 32% to 41%). Indeed, all partisan groups in France studied registered an increase in the percentage who say this.

In the UK and U.S., however, the share who say elected officials care about ordinary people has remained largely unchanged since 2018, although it has risen in the UK among those who identify with Conservative Party and decreased among those who identify with the Labour Party. Today, Conservatives are more likely (61%) to say elected officials care than are Labour Party (41%) supporters. Those who have a favorable view of the Brexit Party (Reform UK) are also more likely than those who have an unfavorable view of the party to say elected officials care what ordinary people think (56% vs. 43%, respectively).

Partisan identity colors opinion about whether elected officials are seen as caring in each of the countries surveyed except for Germany. For example, in France, about two-thirds (67%) of those who identify with President Emmanuel Macron’s party En Marche say elected officials care, compared with fewer than half of supporters of the Socialist Party (43%) and the Republicans (39%).

In the U.S., Democrats are more likely than their Republican counterparts to describe elected officials as caring. Only one-third of Republicans say elected officials care what ordinary people think, compared with about half (52%) of Democrats. This difference in opinion between partisans has flipped since 2018, when Donald Trump was president. At that time, 50% of Republicans said elected officials care, compared with only 36% of Democrats.

There are few differences on this question by age, gender, income or education. However, French men (46%) are 10 percentage points more likely than women (36%) to say that elected officials care what ordinary people think. In Germany, those in the highest income group are more likely than those in the lowest income group to say elected officials care. While in the U.S., those with more education are more likely to agree that elected officials care than those with less education.

Americans largely describe politicians as corrupt, fewer Europeans agree

Two-thirds of Americans say the statement “most politicians are corrupt” describes their country well. However, in France and the UK, publics are more split on the matter, with slightly fewer than half saying most politicians are corrupt. Germans are much less likely to express this opinion.

And in the U.S., while large majorities in both parties believe most politicians are corrupt, Republicans are more likely (78%) to say this than are Democrats (60%).

Partisan differences are relatively muted in the UK, Germany and France, although French supporters of the Republicans (49%) are more likely than En Marche supporters (32%) to describe politicians as corrupt.

In focus groups, Americans and Britons both gave examples of politicians being corrupt

In focus groups conducted in both the U.S. and UK in the fall of 2019, when participants were asked about things that made them embarrassed to be American or British, national politicians often came up.

This was especially true in the UK, as it came up in discussions with groups comprised of both Conservative and Labour supporters as well as those who had voted “leave” or “remain” in the EU referendum. Some Britons cited “expenses scandals” among members of Parliament (MPs) as reasons for why they were embarrassed about politicians. One 33-year-old woman in Edinburgh said that “all MPs are pocketing everyone else’s money.”

In the U.S., discussion of corruption among politicians was related to the notion that politicians can be “bought” by corporations through the lobbying process. In Seattle, participants discussed how they were ashamed of corruption in America, with one participant saying that “it seems like politics are being bought and sold” due to “lobbyists and the special interest groups and all that kind of thing.”

Attitudes about politicians being corrupt or not have not changed significantly in any of the four countries surveyed since the question was last asked in 2018.

Younger people in the UK, France and U.S. are more likely to say most politicians are corrupt. The difference is largest in the UK, where 61% of people ages 18 to 29 say that politicians are corrupt, compared with only one-third of people 65 and older, a 28 percentage point difference.

Respondents in the lowest income group in Germany, the UK and France are more likely to say politicians are corrupt than those in the highest income group in these countries. However, about two-thirds of Americans of all income groups express this view.

Publics largely split on whether ordinary people can do a lot to influence the government

When asked about how much impact ordinary citizens can have on politics, these four publics are somewhat divided. Germans and Americans lean slightly toward the view that “ordinary people can do a lot to influence the government,” while the British and French publics are more closely divided. In France, about one-quarter (24%) say that the statement describes their country “not well at all,” while one-in-five say the same in the U.S. and UK.

In each country surveyed, those who say that they personally have a good chance to improve their standard of living are more likely to say that ordinary people can influence the government.

Only in the U.S. does partisanship play a role in shaping this belief: 58% of Democrats think that ordinary citizens can influence the government, compared with 46% of Republicans.

Citizen assemblies popular, especially among those who want major change to the political system

In all four countries, there is considerable support for the creation of citizen assemblies where citizens debate issues and make recommendations about national laws. Citizen assemblies have become increasingly common in nations around the world in recent years and have been used, for example, in Ireland to decide such contentious issues as abortion and gay marriage.

Citizen assemblies have already been used nationally in France and the UK to debate environmental policy. The French Citizens’ Assembly on Climate, initially convened in October 2019 in response to the Yellow Vest Movement, concluded last year with the release of 149 proposals, though many remain to be implemented.

The country with the largest share of respondents who say such reforms are very or somewhat important is the United States, though about three-quarters or more in each country say it is important to create citizen assemblies. A plurality of Americans say it is very important for the national government to create citizen assemblies; only 21% say it is not too or not at all important.

There are significant ideological differences on the question of how important it is to create citizen assemblies. In France and the UK, those on the ideological left are significantly more likely than those on the right to say creating citizen assemblies is very important.

Respondents who say their country’s political system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed are also warmer toward citizen assemblies than those who say it only needs minor changes or no changes at all. For example, 46% of French respondents who say France needs systemic political change say it is very important for the government to create citizen assemblies, while about three-in-ten who say the political system needs minor changes or no changes say creating citizen assemblies is very important.

In the UK, where citizen assemblies have been used to debate Scottish independence, Brexit and climate change policy, there are significant political differences on this question. For instance, 83% of Labour supporters think it is very or somewhat important for the government to create citizen assemblies, while 66% of Conservative supporters say the same. Those who identify as Remainers are also more likely than those who identify as Leavers to support citizen assemblies.

Majorities say it’s important for voters to decide key issues

In each of the four countries surveyed, majorities believe it is very or somewhat important for the national government to allow citizens to vote directly to decide what becomes law for some key issues rather than letting members of the legislature decide.

A plurality (42%) of Americans say it is very important to decide some key issues by referendum. Views on this question are linked to perceptions of political corruption: 45% of Americans who think most government officials are corrupt say it is very important for the national government to allow citizens to vote directly on key issues, compared with 35% of those who think the phrase “most government officials are corrupt” does not describe the country well. There are similar divides in Germany and the UK.

While the ghosts of referendums past may influence British opinions on this question today, there are no significant differences between those in the UK who identify as Remainers and those who identify as Leavers. However, there are differences based on age. Nearly four-in-ten Britons ages 18 to 29 – some of whom were too young to vote in the Scottish independence and Brexit referendums – hold the view that it is very important for the national government to allow citizens to vote directly to decide what becomes law. This is a higher share than among those ages 30 to 49 (23%), 50 to 64 (27%) or 65 and older (24%).

In the U.S. and Germany, those with less education are especially likely to think it is very important for the national government to decide key issues by referendum. About one-quarter of Germans (24%) with a university education or higher hold that opinion, compared with 43% of those with a secondary education or less. A similar pattern appears in the U.S., with a 14 percentage point gap between those with a secondary education or less (48%) and those with a university degree or higher (34%).

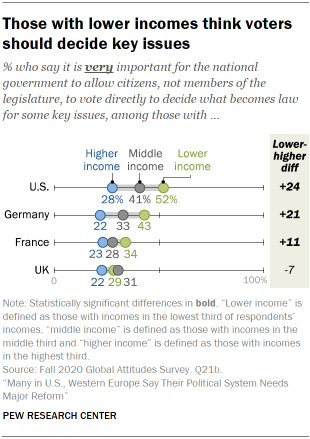

Those with lower incomes are also significantly more likely than those with higher incomes to say it is very important to have referendums. In the U.S., this income gap is 24 points, with about half of lower-income Americans and about three-in-ten higher-income Americans holding that view. There are also significant income gaps of 21 points and 11 points in Germany and France, respectively.

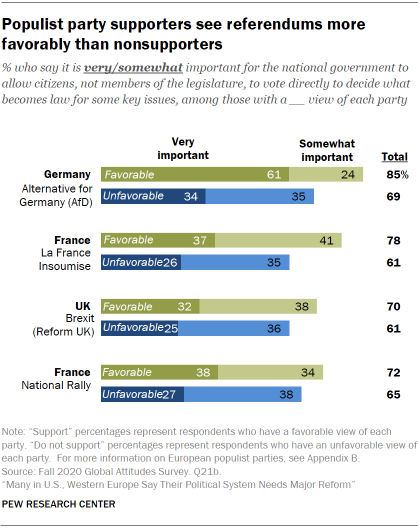

In the three European countries, larger shares of those with favorable views of populist parties think it is very or somewhat important for their government to allow citizens to decide what becomes law for some key issues. This pattern transcends ideology, with more favorable views toward referendums among supporters of the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Brexit Party (Reform UK) and the left-wing La France Insoumise.