In U.S. and UK, Globalization Leaves Some Feeling ‘Left Behind’ or ‘Swept Up’

Focus groups reveal the degree to which Americans and Britons see common challenges to local and national identity

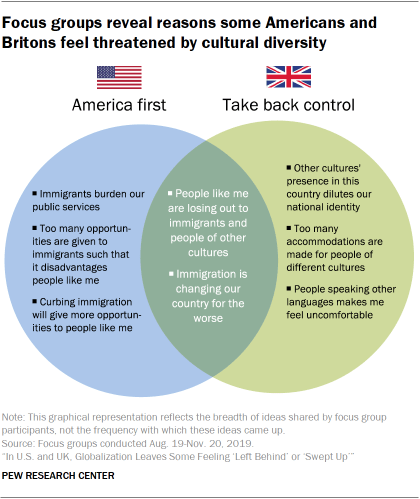

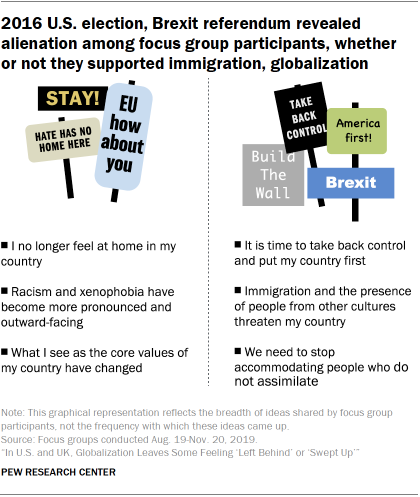

In 2016, both Americans and Britons participated in divisive votes shaped in part by questions of immigration and global engagement. In the United States, voters cast ballots in a presidential election ultimately won by Donald Trump and his “America first” vision. Across the Atlantic, “leave” voters outnumbered “remain” voters in a national referendum on continued European Union membership, framed by the slogan “Take back control.” Attempts to explain the twin poll results have focused on people who felt left behind and who voted against the seemingly inexorable tide of growing economic interdependence, cultural diversity and social connectivity that define a globalized world. But direct, systematic comparisons of the two countries have been rare.

Pew Research Center undertook focus groups in the United States and United Kingdom in 2019 – prior to the outbreak of COVID-19 – to understand better the degree to which similar narratives about globalization and its impacts are evident in each country – and whether these narratives vary by geography, political affiliation or other factors in each country.

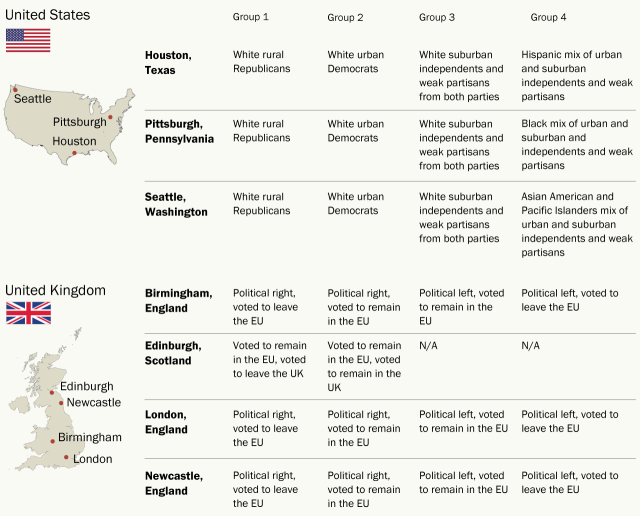

Pew Research Center has been studying issues of national identity and globalization for some time, but this project is the Center’s first foray into exploring the topic using comparative, international focus group data. We conducted 26 focus groups from Aug. 19 to Nov. 20, 2019, in cities across the U.S. and UK, grouped by political and geographic attributes as described below in the table (for more, see the methodology). All groups were asked questions about their local communities, national identities and globalization by a trained moderator. The questions were based on a discussion guide designed by Pew Research Center.

To analyze the data collected from these discussions, researchers reviewed the focus group transcripts and consolidated the sentiments into “data displays.” These displays summarized participants’ responses to the moderator’s questions and included coding schemes to highlight key themes and points of interest in the conversation, as well as the dynamics of the discussion. Researchers analyzed the coded data, focusing on how opinions varied across the groups, which served as the primary unit of analysis. Particular care was taken to ensure that the viewpoints expressed in this report accurately capture the range of opinions expressed, emphasizing not just a majority opinion, but minority and dissenting opinions as well.

The analysis presented in this report is indicative of key narratives and frames of references that influence how people perceive and understand important issues. The findings are not statistically representative and cannot be extrapolated to wider populations. Similarly, while we often refer to groups of participants as “Democratic groups” or “leavers,” these descriptors are shorthand, based on the research design or moments in the focus group conversation. Depending on the topic, a participant’s age, gender, city, employment status or other factors may have been equally relevant to their opinions and views about globalization.

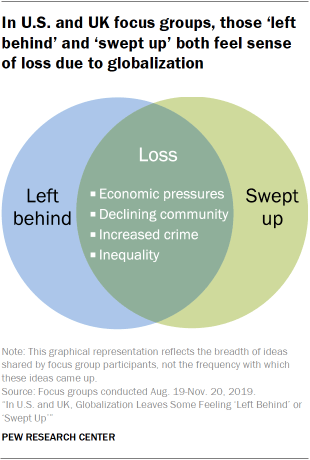

The focus groups confirm that the story of being “left behind” remains common in both the U.S. and UK. Participants highlighted the ways in which the forces of globalization left them rudderless, closing industries, leading people to abandon their homes and harming them economically. But the group conversations also reveal a narrative of being “swept up” by globalization. Those who are swept up experience dislocation because of too much attention from global forces – investment and new job creation supplant traditional work, inflate real estate prices and displace some people from their homes and communities. Stories of being left behind and swept up both lead to feelings of alienation and loss.

Attitudes toward globalization shaped less by local change, more by national context

Click for more information

In academia, this is referred to as a “sociotropic” attitude. Academics have found similar relationships when examining trade attitudes or attitudes toward immigration. For example, when it comes to trade, scholars argue that people’s attitudes toward international trade are based less on their material self-interest than on perceptions of how the U.S. economy as a whole is affected by trade. Similarly, when it comes to immigration, research suggests people’s opinions are shaped by their concerns about the national cultural impacts of immigration more than their personal economic experiences.

Given that people can feel dislocated whether they are left behind or swept up, what separates those who see globalization negatively from those who see it positively is how they perceive changes to their country, rather than their neighborhood. Those who are more locally or nationally rooted tend to see globalization breaking down the national community and changing what it means to be part of the nation-state in ways they find disaffecting. In contrast, those who embrace globalization tend to focus on the ways in which globalization itself can create community – fostering new connections by breaking down boundaries between people to foster international cooperation and understanding.

In the following section, we describe how focus group participants defined and described globalization. Then, we look at how globalization impacted participants’ local communities and created a sense of loss, both for those who were left behind and those who are swept up by globalization. We then look at how people see globalization changing what it means to be British or American and how both those who are more globally oriented and those who are more nationally rooted express feelings of alienation in their country. Finally, we look at participants’ attitudes toward globalization at the international level, concluding that some view global interconnectivity as an opportunity for cooperation while others see it as a battleground for competition. Throughout the essay are quotations representing a range of views from participants, some of which have been edited for grammar, spelling and clarity.

Key findings and road map to the essay

The term “globalization” was difficult for participants to define, but it was not difficult to describe.

Whether groups felt their communities were globalization “winners” who experienced job creation in their city or “losers” who felt the decline of industry, people focused on the changing character of their communities, the increased transience and the declining opportunities. Those “left behind” by globalization and those “swept up” often experienced similar feelings of loss and assigned blame to multinational corporations.

People in the UK and U.S. felt that what it means to be British or American, respectively, is changing. Participants who are more inwardly oriented focused on how multiculturalism was “diluting” the dominant national character. People who were more globally oriented focused on how Brexit and the 2016 election have left them feeling like their country is no longer the multicultural, accepting place they had prized it to be. For separate reasons, participants highlighted their alienation and confusion about what it means to be part of their nations today.

Participants who are less open to globalization tend to view the international sphere through the lens of the nation-state and as competition, expressing a need to stand alone apart from the interference of international bodies.

Participants who are in favor of globalization see the ways in which community can exist internationally, separate and apart from national boundaries.

Regardless of their comfort with globalization, participants highlighted its inevitability.

Globalization: You know it when you see it

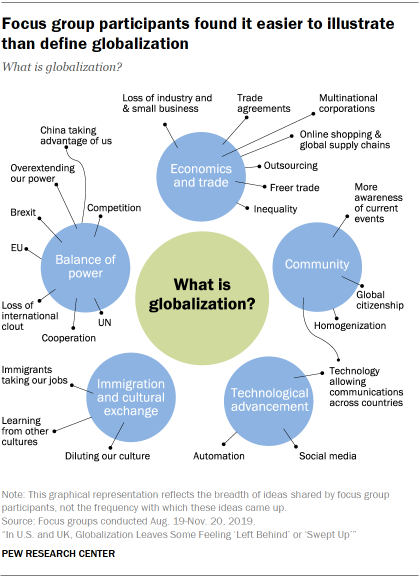

The question “What is globalization?” was not easy for focus group participants to answer. Definitions were wide-ranging, touching on economic changes such as the rising influence of multinational corporations and the role of international trade; international organizations like the United Nations; immigration and the movement of people; and amorphous concepts like the exchange of ideas and cultures. As a further indication of how challenged participants were by the task of defining globalization, some offered a response, only to hurriedly seek confirmation from the moderator that their answer was “correct.”

Though participants were often unsure of how to define globalization, key themes did emerge. These centered on economics and trade, the global balance of power, immigration and cultural exchange, technological advancement, and community.

And unlike technical definitions, participants found it relatively easy to share illustrations of globalization. They brought up the impacts of globalization on their daily lives, like the experiences of calling customer service and reaching a call center in another country. People touted the ability to order goods from the other side of the world on Amazon and have them delivered the next day. Others brought up how immigration has shifted the fabric of their country for better or worse, or how openness to foreign ideas and customs was changing their country’s culture – again, for both better and worse.

Globalization and change at the local level: Whether left behind or swept up, feelings of loss pervade

When describing key changes in their local communities, participants did not always invoke “globalization.” Yet their stories often linked to broader illustrations of what constitutes globalization. This was particularly true when participants spoke about changes due to industrial shifts, automation and the growing influence of multinational corporations. All three were consistently described as negatively impacting local communities – in contrast to growing cultural diversity or improved communication technology, which were sometimes viewed favorably.

Who is left behind?

Who is swept up?

Click for more information

Though academics and journalists have widely used the term “left behind,” participants infrequently used it themselves. Here, we use the term “left behind” to discuss people who experienced losses like the closure of factories, institutions and local shops or the loss of jobs and opportunities.

We also use the term “swept up” to discuss people who experienced losses associated with growth, like mounting costs of living and increasingly crowded cities.

Some participants described elements of both phenomena. For example, in London, where participants complained of increasingly expensive housing and constant development, participants also lamented the loss of local pubs and decline of high streets.

Industrial change, automation and the influence of multinationals were prime catalysts in stories of being left behind by globalization. Being left behind was often equated with job loss and shuttered businesses. Depending on the locale, participants described either industry-specific or general job losses. Focus group participants in Pittsburgh and Newcastle were particularly animated by stories of being left behind, describing how they or people they knew had lost jobs at coal mines, steel mills and other industrial facilities.

In these cities and elsewhere, participants pointed to the carry-over effects of job loss – from local stores being unable to remain profitable to neighborhoods becoming less prosperous and more dangerous, exacerbated by the onset of crime and drug use that accompanied peoples’ material decline. People who felt left behind also noted the impact of economic decline on local social ties. Participants linked falling rates of homeownership with growing numbers of “transient” renters and less meaningful relationships with neighbors.

What is a high street?

Click for more information

In the UK, a “high street” is defined by the Office of National Statistics as “a cluster of 15 or more retail addresses within 150 meters.” But focus group participants used the term colloquially in much the way Americans would describe a “main street” in a town. The term evoked the center of commercial life and activity.

Job loss was sometimes described as almost a trap. Participants in Newcastle highlighted how their area simply receives less in terms of job training, education and employment opportunities now than they used to, making recovery from job loss more difficult to bear. The same was true in Pittsburgh, where one woman noted that “the market is now changing [and] the people that are already here … are no longer benefiting from it.” Another man commented about how Pittsburgh used to be a blue-collar town but it doesn’t ring true anymore.

For some, these perceived changes and the loss of jobs or opportunities in their town were met with great sadness, while others responded with a more matter-of-fact attitude and seemed to accept these changes as an inevitable fact of life. For example, one man in Newcastle framed the loss of these jobs simply as a result of changes in the labor market, saying, “The job trends are changing – heavy industry’s no longer up here, and we’re getting more offices. … People are coming in from different parts of the country, different parts of the area.”

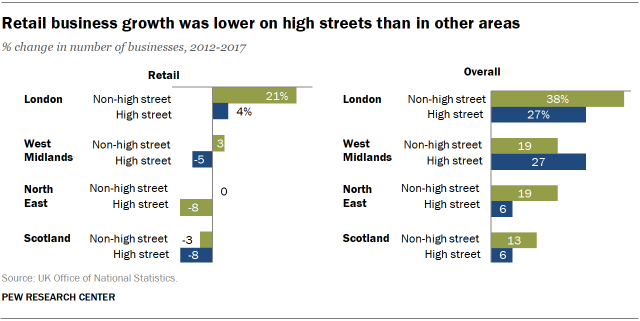

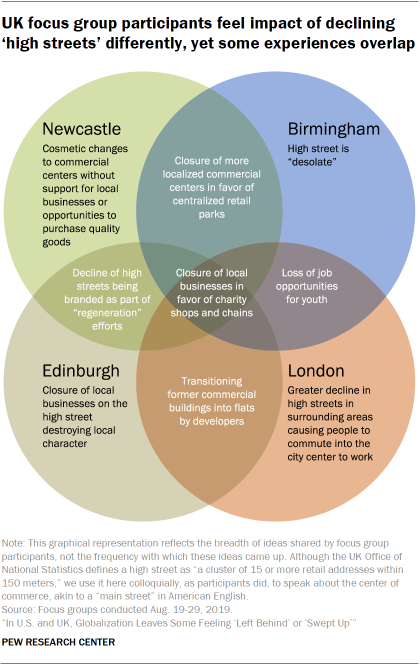

Across the UK, participants lamented the decline of high streets – used colloquially in much the way Americans describe a “main street” but formally defined by the UK Office of National Statistics as “a cluster of 15 or more retail addresses within 150 meters.” They described the closures of independent businesses in their area and the increased presence of charity shops, or thrift stores, and chains.

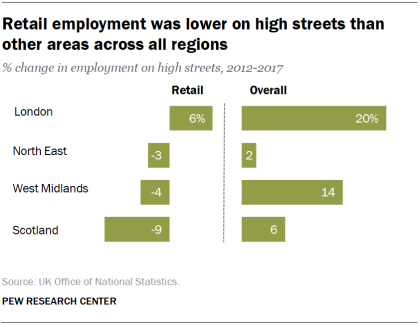

Data from the UK Office of National Statistics indicates that between 2012 and 2017, the regions in which the focus groups took place all experienced either negative or stagnant growth in high street retail.1 But, when accounting for food service, accommodations and other sectors beyond retail, all four regions experienced growth during that period, both on high street and elsewhere, suggesting that perceptions of decline may be heavily colored by retail, in particular.

Looking at employment, a similar trend emerges. In many of the cities where groups were conducted, participants expressed concerns that the declining high streets meant limited employment opportunities. Yet, in the regions where the groups took place, employment on high streets actually grew when accounting for sectors beyond retail, even while employment on high streets in retail fell in all regions but London. And while London did see growth in retail employment on high streets, it was roughly even with the city’s population growth, which also stood at 6% between 2012 and 2017.

The closures and changes people described extended from the workplace to the “high street” in the UK, and the tone was often one of profound loss. In all four cities in the UK where focus groups were conducted, people noted the closure of independent businesses on the high streets, highlighting how these shifts left them feeling like the previous epicenter of their community was no longer the bustling center of commerce.

Often, the blame was laid at the feet of globalization. For example, one woman in Newcastle highlighted how globalization means “smaller businesses … go out of business because [of] competition from … worldwide companies.” Participants also highlighted how these changes negatively impact young people’s job prospects, because with the closure of shops, there are fewer employment opportunities.

There was also a sense that the decline of these high streets was impacting individuals’ daily lives and routines, with one woman in Newcastle saying that in the good old days you could get everything you needed on the main road, but now “it’s degenerating, it’s a s—hole.” Participants described how the commercial decline was uneven, noting strip malls and retail parks getting huge amounts of investment as mom and pop shops on the high streets were left to die out.

“Opportunities [are] about careers, and you look at the average high street now and how that’s changed in 20 years … this is a completely different world for people to get jobs.”

MAN, 38, BIRMINGHAM

The demise of high streets also extended to concerns about the erosion of each city’s local character and charm. In the UK, particularly among Leavers, homogenization was a focus, with participants defining globalization as the “breakdown of individuality” and “everywhere being the same.” Once again, the blame for this perceived homogenization was placed on multinational corporations. One man from London pithily described it as “Starbucks [and] McDonald’s [causing] every high street [to] look the same.”

In addition to the decline of high streets, participants in the UK lamented the closure of local pubs and youth clubs. These places were viewed as key community-building institutions, and their loss was seen as a death knell of social cohesion in their area, ushered in by changing business and industry. Groups described local pubs as gathering spaces for members of the community to build relationships and get to know each other, discussing how their closure meant people did not bond anymore. Youth clubs were also seen as pillars of communities, and groups suggested that their demise has pushed young people onto the streets to cause mischief and engage in criminal activity.

“They’re putting loads of money into [the retail park] but [on] the high street, everything’s closing down …”

“That’s right, yes, unless it’s a charity shop [thrift store] or a coffee shop …”

“Or a Gregg’s [a major UK bakery chain].”

Exchange among woman, 32; man, 52; and man, 34, all of Birmingham

In the U.S., similar tropes emerged. People focused on how there were limited employment opportunities, unfair competition between small businesses and chain retail stores, and large companies threatening the character of their neighborhood. But in the U.S., these complaints focused less on specific commercial districts – like a main street – and extended to the community more broadly.

While the general theme of decline was common across the two countries, an alternate narrative of being swept up by global currents of change also emerged. This sense was palpable across several focus groups in Seattle. All groups there agreed that local investments by multinational corporations like Amazon, Microsoft, Boeing and Starbucks had led to a major influx of people and money, which had put upward pressure on the cost of living in the city.

Seattle focus groups composed of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and of White Democrats shared stories about gentrified neighborhoods, highlighting how housing had become less affordable and how the city’s growth had eroded its culture and character. Groups composed of White Democrats and White independents focused on increased homelessness due to the rising cost of housing. In groups made up of White independents and Republicans, people highlighted how the city’s growth has overwhelmed public services and how local governments have not dealt appropriately with the influx of people and money into the city.

Across the Atlantic, the narrative of being swept up by globalization was most evident among focus groups in London. Participants noted how the city’s position as an international hub, or “magnet,” affects daily life for Londoners. Examples of negative impacts included increases in traffic, crime and housing costs, plus constant construction. Some mentioned that, paradoxically, all of this growth actually meant fewer employment and housing opportunities for local residents. One woman, for instance, faulted “overseas investors” looking to profit off of the city’s housing shortage with the construction of luxury flats that sit vacant when the city was in need of affordable housing.

Although they experienced globalization differently, groups who felt swept up pointed to some of the same outcomes as those left behind, such as the rising cost of housing, declining home ownership and the disintegration of social ties and community. Similar stories also surfaced with respect to increases in local homelessness, drug abuse and crime.

Both those swept up and those left behind saw others benefiting from the very forces of globalization they found so disruptive and disorienting. When probed to say more about who or what has benefited from globalization, American participants regularly suggested that it was “the wealthy,” “the 1%” or “powerful people.” Similarly, participants in the UK described beneficiaries as “white-collar,” including business owners, heads of corporations and generally those in positions of power.

The perception of globalization creating “winners” and “losers” was based on local stories. In Seattle, Houston and London, local residents who worked in sectors such as technology and health care were seen as more capable of earning good wages and keeping up with the rising cost of living. By contrast, people in other sectors were described as bringing home meager wages and struggling to achieve financial stability.

Both those who felt swept up and those left behind agreed that the wealthy were largely immune from the effects of globalization. In London, one 26-year-old Conservative “leave” voter noted that the wealthy “don’t necessarily feel the impact of that population boom” in his city because they do not have to go to overcrowded schools and generally do not rely on the public services like social housing, health care, and other public provisions that have been overburdened in the UK.

Whether feeling swept away or left behind, focus group participants in both the U.S. and UK punctuated their stories about local change with a profound sense of loss – loss of financial security, loss of employment opportunities, loss of social solidarity. And while participants may not have often used the precise term “globalization,” they nevertheless laid the blame for their losses at the feet of global actors, especially multinational corporations.

Between tolerance and tradition:

Globalization, culture change and national identity

Unlike the consistent picture of globalization’s negative impact on local communities, focus group participants in the U.S. and UK differed on whether globalization was a boon or bane for their respective countries. Yet even those who, as a matter of principle, welcomed immigration and cultural diversity ultimately admitted to feeling out of place in their own country. But in their case it tended to be related to concerns about the forces they perceived as “anti-global” in their country – people who insisted on protectionist or exclusionary agendas under the banners “America first” and “Take back control.” Ironically, both positive and negative narratives of globalization’s national-level impact left participants feeling alienated and adrift.

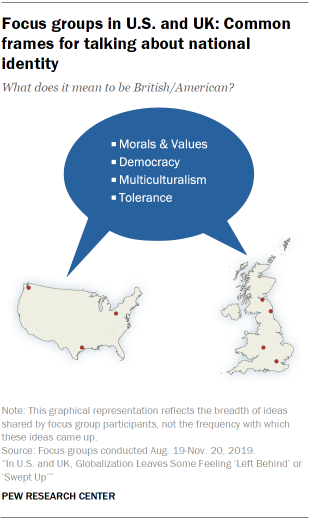

Participants see and feel globalization changing what it means to be British or American because of the flow of people, cultures and ideas. Regardless of political orientation, most focus groups began their discussion of what it means to be British or American by emphasizing multiculturalism and tolerance. They also overwhelmingly highlighted the benefits of globalization in terms of the diversity of options available in their country: available goods, cuisines, cultural offerings and the like. Even one man who voted “leave” and highlighted his general disapproval of immigration noted that he “likes [his] curries,” referencing the abundant Indian and Pakistani food offerings in his community.

“You can eat pho … for breakfast. You can have some pupusas later on. You can have some tacos later on. You can have barbecue. You could have crayfish. … The music … you get to experience different cultures … I mean, you can’t beat that.”

MAN, 21, HOUSTON

But, particularly for those in groups composed of “leave” voters and Republicans, the limits of this comfort with globalization and multiculturalism came when there was a corresponding sense that these cultures were changing British or American culture, or immigrants and foreigners were benefiting at the expense of locals. In the UK, one older woman from Birmingham summed up the sense that the national culture is changing, declaring, “[Our] Britishness is being diluted because of all the other cultures coming in here. … If there was a fair ratio of people that the country could cope with and it wasn’t draining all of our resources, then it’s fine. … I think it’s nice to experience other cultures and share … but now it’s like that blend has taken away the Britishness.”

Those who were less comfortable with immigration tended to couch their discomfort in discussions of differing “values” or parenting strategies. For example, people highlighted wanting to be around people who pay their fair share and are morally upstanding, qualities they often attributed to themselves while contrasting themselves with people from other cultures.

One woman in Birmingham shared that she thought Pakistani people were too different from other Britons because they “eat with their hands” and suggested that immigrants don’t believe in British values so they should “go back home.” In some “leave”-voting groups in the UK, when prompted, participants explicitly said they wanted to live in predominantly White, British areas, claiming that people from other cultures could not meet their standards for morality and that people naturally preferred segregated neighborhoods.

People also highlighted the way immigration could be alienating, changing how it felt to be “British” in public. For example, one older White “leave”-voting woman in London said she finds it “awful” to get onto the tube and hear people speaking myriad languages, describing it as a “very hostile environment” for her. In Birmingham, another “leave”-voting woman told an extended story about her experience giving birth in a hospital and having no midwives who spoke English, which made her feel like a minority and caused her to feel unsafe and un-cared for.

“We can trade between countries; the shop down the street from me is mostly Polish but also sells things from Spain and Cyprus, and sometimes it’s nice to go in there and buy food from another country that you wouldn’t necessarily get elsewhere.”

Woman, 32, Birmingham

Ideologically right-leaning groups especially stressed that traditional culture – which some equated with Christianity – was relegated to second-class status in the country. People highlighted perceived double standards, such as schools accommodating other religions – teaching about Diwali or banning sausage rolls – but forcing the annual winter holiday celebrations to be just that, and not Christmas parties.

In the workplace context, one older man in Birmingham suggested he would have difficulty getting time off to go to a christening but that there are prayer rooms for Muslims to take regular breaks. Other cultural practices such as flying the St. George’s Cross to express English identity were seen as impossible for fear of offending others, or worse, for fear of being labeled a racist by others in the community.

In the U.S., too, participants highlighted the times at which accommodations for immigrants or perceived foreigners limited options for people seen as deserving natives. For example, in Houston, participants in the Republican group balked at the number of jobs in their area requiring bilingual applicants, saying that it gives an unfair leg up to Hispanic job seekers. Some felt this was part of a broader trend of disadvantaging White Americans and highlighted the ways in which restricting immigration could lead to more resources for “locals.” A man in Seattle exemplified this sentiment, saying, “Immigrants have more rights than we do” and get more benefits. He added that he “resents [his] tax dollars paying for someone who’s not feeding into the tax system, whether they are Americans or illegal.” In other instances, immigrants, by their mere presence, were as seen as devaluing homes since, according to one woman in Pittsburgh, they have “eight households [living] in one house.”

“I think the British list that I thought of was … loose national project of making a multicultural, prosperous, liberal, strong nation, which punches way above its weight on the international scene … but it’s looking kind of shaky now, a bit wonky, because we don’t know who we are any more. I don’t, I’ve never felt less British. I’ve always had a strong British identity. … And [now] all I want to do is run, I want to get out of here. I don’t want to be part of this. It looks shambolic.”

Man, 53, London

This sense that what it means to be American or British is changing today – and the corresponding alienation and loss – was not felt only by focus group participants who opposed global interconnectivity and multiculturalism. For those who were supportive of their nation-state’s integration into the global community, the Brexit vote in the UK and the 2016 presidential election in the U.S. presented similar feelings of loss and alienation in society, as well as a changing sense of what it means to be British or American today. While both elections were not solely focused on these themes, both events focused, at least in part, on inherently international questions: how to control immigration, how to secure borders, how to participate in international organizations, and whether to pursue “America first” policies or to “take back control” from the EU.

Whereas some focus group participants may have felt alienated because of a perceived sense that immigration is changing their culture, on the flip side, those who want their country to be part of the EU or to remain involved in the international community and welcome immigrants feel disaffected because of how those events have changed the way they view their nation-state and their place in it.

In the UK, for example, the Brexit referendum was regularly touted as a profoundly alienating moment, exposing people to a side of Britain they hadn’t seen before and highlighting the political divisions in the country. For people in “remain”-voting focus groups especially, it signaled to them that they are a minority in their country – in terms of their beliefs for some, and in terms of their ethnic identity for others.

Participants spoke more openly upon recognizing they shared points of view

Click for more information

This feeling created an interesting dynamic in some focus groups, as participants did not know how the groups were selected. Respondents often skirted around sensitive political or cultural issues, speaking in vague terms or euphemisms, until conversation had advanced to a point where they felt confident that many or most of the people in the room with them shared their viewpoints. In some instances, as this would happen, the moderator would even confirm for people that they were in a room of like-minded individuals on a particular issue (most regularly that they were Brexit “leave” voters). At that point, the tone of conversation would palpably shift and people would appear more relaxed when discussing sensitive topics.

As one man in Birmingham said, recalling the day after the referendum, “It was quite surreal … this doesn’t represent me … [Britain] doesn’t feel like home anymore.” One Black woman of African descent in Birmingham told a story about going to vote with her husband in the Brexit referendum in 2016, saying, “I think it’s the first time in a long time when I could feel the blatant racism in the room. We walked into the school where we were voting and everybody turned around to look at us.” Another “remain” voter of Bangladeshi descent in Newcastle said she had felt at home until Brexit, but she has now lost friends because Brexit “[brought] out the inner racist. … Personally, I feel my life’s completely changed since Brexit.” On the other hand, those who voted “leave” shared stories of being vilified by remainers as xenophobes or racists.

“I used to think that we really believed what Emma Lazarus wrote in her poem, that’s on the base of the Statue of Liberty. And now it’s, ‘Give me your tired, your poor, as long as they’re White, Northern European.’”

Woman, 70, Houston

In the U.S., too, especially in focus groups composed of Democrats, people highlighted that the 2016 election had shaken their belief in the core values of the country. As one man in Houston said, “I feel like we were more welcoming of immigrants … now it seems like there are people that don’t want certain immigrants … Brown [immigrants]. It’s always been like … ‘Come here, this is the American Dream’ … I feel like that’s really being squashed.” Some explicitly faulted President Trump for the change, saying he has inflamed things, “egging on” racism. A young Hispanic woman in Houston noted, “Once upon a time, there were people who were racist, but they kind of kept it behind closed doors. … But now it’s way up in the forefront … you see people just spewing hate at innocent folks because they heard someone speaking a different language in Taco Bell.”

The sense of not feeling at home in one’s country was also expressed by those who voted “leave” in the UK and for Donald Trump in the U.S. Leavers and Republicans alike discussed how the “out of control” levels of immigration and the accommodations immigrants receive may have created a deep sense of alienation in their own country and a corresponding sense that, if they share this opinion with others with different viewpoints, they will be castigated. For some, this has translated into lost friends or personal animosity, with people on both the political left and right offering examples of losing friends – or being unfriended on social media – because of different views over political candidates.

“I’m fair skinned and my brothers are darker skinned … being out in public, people give them the once over … it’s disheartening for me … we didn’t have that problem a few years ago out in public. [Also,] at dinner with some acquaintances … they started talking crap about Latinos. I [said,] ‘You know, as a Mexican … I disagree with you,’ and he goes, ‘Oh, but you’re one of the good ones, so I wasn’t talking about you.’ – I feel like that statement wouldn’t have been made five years ago.”

Woman, 19, Houston

In both the UK and the U.S., participants also explained how they felt polarization has deepened in their country. One American noted that it’s currently “traumatic” to be American, saying, “I used to have an identity of what American meant and it’s devaluing.” Another described America as “tribal,” saying “There’s no compromise, no common sense. No listening to other people. Political tribes.”

“It’s on the verge of civil war. Not a racial civil war. It’s a political civil war.”

Man, 51, Pittsburgh

While the changes participants saw in their countries and the perceived catalysts of those changes varied, nearly all participants said these shifts were causing them to feel disconnected from their national identity. For some, globalization in the form of immigration and multiculturalism had wrought too much change, to the point that they felt they could no longer recognize their country. They noted that they couldn’t feel a connection with others under the mantle of being “British” or “American” because the culture had been eroded too much and that some people grouped under that label felt too different from them.

“We’ve lost our identity as a people. We’re fighting each other. Us and them. A house divided … on socioeconomic [status], race, gender, just pick something [and we’re divided].”

Man, 58, Houston

For others, pivotal events marking a political shift away from the globalized world and toward a “country-first” national character alienated them from how they used to conceptualize and understand their countries. For these people, community and national identity meant welcoming people from elsewhere and blending cultures, foods and ideas.

Despite fundamental differences in how they characterize their countries, both groups of people were reticent to label themselves as “cosmopolitan.” Even those who supported the principles of a globally oriented world tended to describe “cosmopolitans” as elitists who were “out of touch” or were wealthy jet-setters, evoking images of a “Sex and the City” lifestyle. And even while globally oriented and nationally rooted people both were disillusioned with what it meant to be British or American today – albeit for different reasons – there was a discomfort with identifying as a “citizen of the world” or, as Theresa May evoked, a “citizen of nowhere.”

Sovereignty, competition and community in a globalized world

As described above, disruptions linked to globalization have engendered profound feelings of loss and alienation at both a local and national level. In response, some focus group participants expressed support for “taking back control” – the slogan of the Brexit campaign – or putting “America first,” the oft-repeated slogan of the 2016 Trump campaign. For these participants, the international sphere is perceived as a space of competition, with a focus on the nation-state. In contrast, focus group members who expressed feeling alienated less by globalization, and more by nationalist rhetoric and policies, tended to highlight opportunities to create a sense of community at the international level. Those with the latter mindset emphasized the importance of cross-border interactions between people, cultures and countries and the ways nation-states can cooperate rather than compete.

In the course of the focus group discussions, participants observed that globalization extends beyond economic issues, such as trade, multinational corporations and open markets, to questions of governance, sovereignty and the connectivity made possible by new communication technology. Core to the discussion of globalization’s political implications was the role and influence of multinational or multilateral organizations such as the UN, the World Bank and – in the case of the UK – the EU. Particularly for participants who were less comfortable with globalization, these organizations were framed in terms of implications for the nation-state.

“[America] should stop being so dependent on [competitor countries] and should be more stern with them. But climate change and terrorism are global issues, and it takes a village to solve them. [The U.S. should] keep its friends close and its enemies closer.”

Woman, 52, Seattle

In groups composed of Republicans and Conservatives in the U.S. and UK respectively, participants evoked the notion of sovereignty and their country’s right to self-determine if, how and with whom to interact on the world stage. Some in the U.S. claimed that organizations like the UN and the G7 were avenues for “global government” or other countries to assert power over the country and “try to tell everybody what to do.” Respondents in Republican groups stressed power discrepancies – highlighting the ways in which America has been taken advantage of by countries like China. For global skeptics in the U.S. focus groups, a recurrent theme was American leadership and preservation of the country’s self-interest, even in the context of multilateral cooperation. As one Seattle woman said, “America should be the leader” and “set an example.”

In the UK, history of empire colored views of nation’s place in the world

Click for more information

In the UK, the issue of history and empire was front and center in these discussions. Those who were least comfortable with globalization tended to harken back to the British Empire and to glorify the role of the nation-state historically. In contrast, those who tended to be more accepting of globalization were more likely to suggest that reconceptualizing history – and the UK’s role internationally – was merited. For example, these participants noted that the UK needed to think of itself less as a powerful, historic maritime power and more as part of a global community. As one Scottish participant noted, “We think we are more important in the world than what we probably actually are. We are a tiny island. We seem to be told that we are this global superpower all the time, but actually our power is getting less and less, and I think people need to be aware of it and start being a bit more realistic about what’s going to happen in the future.”

A different story emerged among “remain” groups in the UK. Here, participants observed that their country’s current standing in the G7 and other organizations owed to a history of international influence that had placed the UK high up in the “global pecking order.” The idea of competition among nation-states was pervasive, with participants using sporting analogies to describe how the UK today could “punch above its weight” on the world stage or be “one of the big players” globally.

In both countries, participants discussed competition between nation-states in terms of economic, as well as political influence. Global trade was often framed as a zero-sum game. Trade was about one’s own country benefiting at the expense of other states. One man in Pittsburgh commented that the U.S. risked becoming “poor” if it disengaged from global trade and could no longer “manipulate other countries to get their resources.”

“I used to work for a company [that bought rubber] manufactured locally. And then it worked out it was a pence cheaper to get [the rubber] in China, so it all went out to China … the knock-on effect of one of those plants shutting down and the guys that supply their raw materials and everything.”

Man, 48, Newcastle

Especially in the American focus groups, there was a heavy emphasis on outsourcing, with people mentioning changes such as less desirable jobs moving abroad and the growth of overseas call centers. Participants fixated on how the U.S. was “losing” this zero-sum game to countries like China or India – countries that “won” by virtue of manipulating currency or flouting environmental regulations. This idea also materialized in discussions about trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (which has since been replaced by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement).

“If you tell a company in America, ‘Hey, you can move your manufacturing wherever, and we won’t charge you for it’ … well of course they’re going to do it. Because in other countries, they can manufacture whatever, and then they can just dump their waste into the river because they don’t have the environmental controls that we have.”

Man, 53, Pittsburgh

But not everyone saw the international arena as one of nation-states in competition. Participants also talked about the possibility – and importance – of countries “working together to solve problems that the entire world faces.” In focus groups on both sides of the Atlantic, people emphasized that their country was often ill-equipped to independently tackle large-scale issues like climate change or terrorism. Others discussed how solving complex issues was not possible for one country to do on its own without drawing on the resources and expertise of other countries. Even skeptics of globalization acknowledged that cooperation, at least to some extent, was necessary to solve complex issues.

“We need to be educating and sharing. … Certain countries have gotten better expertise and that kind of thing in certain fields, and they can share knowledge.”

Man, 46, Birmingham

In some cases, international cooperation was described as a responsibility. For example, one Labour-supporting “remain” woman in Birmingham noted that “every person is responsible for climate change,” regardless of where they live. The same was also true when it came to issues like public health (though these focus groups took place before the global outbreak of COVID-19).

“We can’t solve [international problems] on our own, anyway.”

Man, 68, SEATTLE

Participants who saw globalization as an opportunity, as opposed to a threat, also talked about personal forms of international community made possible by advances in communication technology. For some, this was portrayed as an alternative to feelings of local or national solidarity weakened by global forces. The speed and pervasiveness of social networks was described as enabling communication “instantly across the world” and creating the possibility of a “worldwide community” that can provide “support when something happens all over the world.”

“[Globalization] could only be a good thing … sharing knowledge instead of, like, ‘This is our information, and this is their information.’”

Woman, 47, Pittsburgh

Others spoke about even more personal forms of international community, such as a man in Seattle who shared that, thanks to online connections, he had found a small but global group of people who had gone through the same jaw surgery that he had. Another man in Houston shared how, as a hiring manager, he couldn’t find qualified Americans to fill certain roles, so he has had to reach out to people overseas. For participants like these, technology and other products of globalization were viewed as a means to forge connections or bonds with people beyond their local and national communities.

Participants also stressed the ways in which people and ideas could flow, creating webs of interconnectivity and interaction that weren’t bounded by national borders. They pointed to the role of technology in education as providing “long-distance learning for the world.” One woman in Houston noted, “It’s no longer about one nation, it’s the entire … everything impacts everything else,” while another Houston woman stressed that globalization involves “recognizing that we are all passengers on spaceship earth … [and] share a common interest.” Core to this discussion was the sense that globalization involved the evolution of an “open marketplace for the world,” with “flattening borders” that reduced countries to mere “passport designations” or destinations for Amazon deliveries.

“I think because of the internet, we have to start looking at ourselves as part of the planet earth, not Americans, not Italians, not Mexicans, whatever it is, we’re coming to the place where we’re going to have to be earthlings.”

Woman, 72, Seattle

While these focus groups were diverse and stretched across the U.S. and UK, their participants largely viewed globalization through one of two lenses: fostering an arena of international rivalry and competition, or creating the possibility of new cross-border communities. Among the former group, increased international connections have meant greater insecurity and threats to their country’s ability to maintain power and influence. For the latter group, globalization has come with perceived opportunities, and even obligations, to connect with others, find common cause and tackle global problems.

Disruptive … but inevitable?

Across the focus groups, participants in the U.S. and UK consistently agreed on one thing: Their communities, their countries and their worlds are changing. While the term “globalization” did not always roll off their tongues, participants concurred that the catalyst for change was an increasingly interconnected world in which multinational corporations, foreign trade and multilateral organizations had become important factors shaping local and national identities.

Whether people described being swept up by influxes of money and people, or left behind as jobs and investment moved elsewhere, the experience of globalization was often described in terms of “loss” and no longer feeling at home in one’s community or country. In some instances, these feelings led participants to sympathize with nationalist appeals to “take back control” or put “America first.” Others were less invested in defending local and national identities; they saw opportunity in the form of new social ties beyond their immediate locales and new international forms of solidarity, abetted by travel, digital connectivity and a sense of shared priorities across national borders.

Above all, the general sense among focus group participants is that no matter one’s politics, location, career or position in life, globalization is here to stay. Participants generally agreed that change at the local and national levels will continue, driven by increased international connectivity. Industries will continue to shift, societies will continue to wrestle with issues of multiculturalism, and technology will continue to alter the pace and pattern of cross-border ties and identity.

Methodological note

This cross-national, comparative qualitative research project was designed to explore more fully how local context and national identity shape opinions about globalization. Analysis is based on the 26 focus groups we conducted across the U.S. and UK in the fall of 2019 and more information about the groups and analysis can be found here and here.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. This report is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of a number of individuals and experts at Pew Research Center.