Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand what Americans think about how nations around the world are responding to the coronavirus outbreak and what Americans think about international engagement. For this analysis, we surveyed 10,957 U.S. adults from April 29 to May 5, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

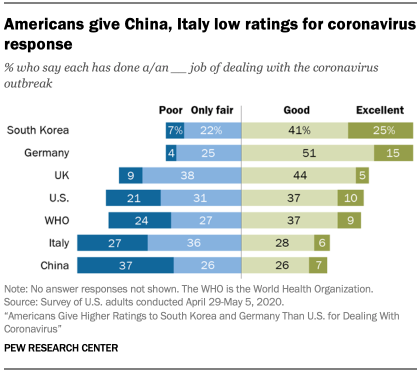

With stunning speed, the COVID-19 pandemic has swept across borders, claiming victims and shutting down economies in nations across the globe. The crisis has generated a variety of policy responses from governments, with varying degrees of success. When asked how well different countries have responded to the outbreak, Americans give high marks to South Korea and Germany. In contrast, most believe China – where the pandemic is believed to have originated – has done an only fair or poor job.

With stunning speed, the COVID-19 pandemic has swept across borders, claiming victims and shutting down economies in nations across the globe. The crisis has generated a variety of policy responses from governments, with varying degrees of success. When asked how well different countries have responded to the outbreak, Americans give high marks to South Korea and Germany. In contrast, most believe China – where the pandemic is believed to have originated – has done an only fair or poor job.

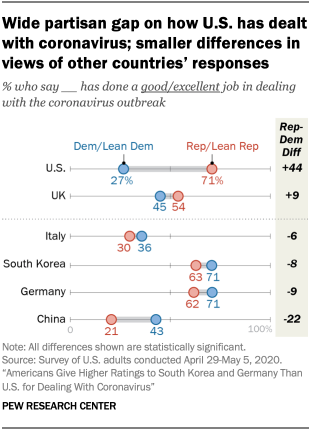

Most are also critical of Italy’s response, while the public is divided over how well the United Kingdom has dealt with COVID-19. Regarding their own country’s reaction, Americans are divided along partisan lines. Overall, 47% of adults say the United States has done a good or excellent job of handling the outbreak, but just 27% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents hold that view, compared with 71% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.

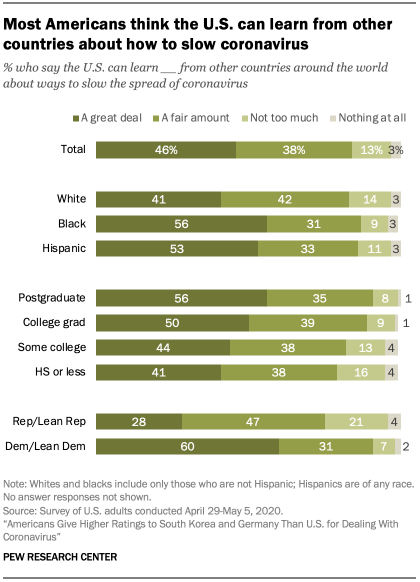

Americans largely agree the U.S. should look beyond its borders for ideas to combat the coronavirus. Nearly half (46%) say the U.S. can learn a great deal from other countries about ways to slow the spread of the virus, while another 38% say it can learn a fair amount. Few say there is not too much (13%) or nothing at all (3%) the U.S. can learn from other countries.

The leading international organization for dealing with global health issues, the World Health Organization (WHO), draws strongly partisan reactions. While 62% of Democrats believe the agency has done an excellent or good job of dealing with the pandemic, just 28% of Republicans agree. Eight-in-ten Democrats trust coronavirus information from the WHO; only 36% of Republicans do so.

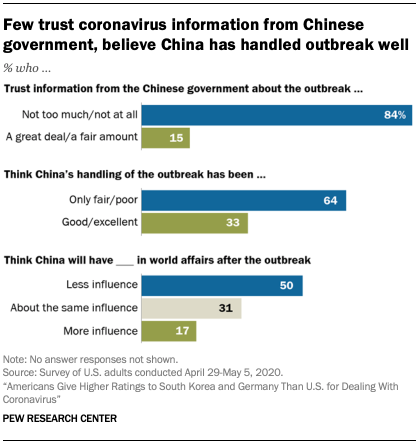

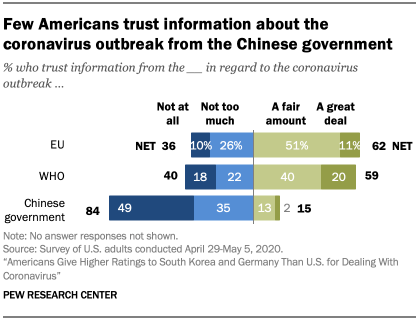

There’s more agreement, however, when it comes to information from the Chinese government: 84% of Americans say they place not too much or no trust in information from Beijing regarding the coronavirus outbreak.

There’s more agreement, however, when it comes to information from the Chinese government: 84% of Americans say they place not too much or no trust in information from Beijing regarding the coronavirus outbreak.

Many also believe the current crisis will have a long-term impact on China’s global stature: 50% say China will have less influence in world affairs after the pandemic. As a March Pew Research Center survey found, overall negative attitudes toward China have been on the rise – 66% of Americans expressed an unfavorable opinion of China, the most negative rating for the country since the Center began asking the question in 2005.

While unfavorable views of China have increased among both Democrats and Republicans over the past two years, there are nonetheless significant partisan differences in attitudes toward China, with Republicans expressing significantly more negative attitudes.

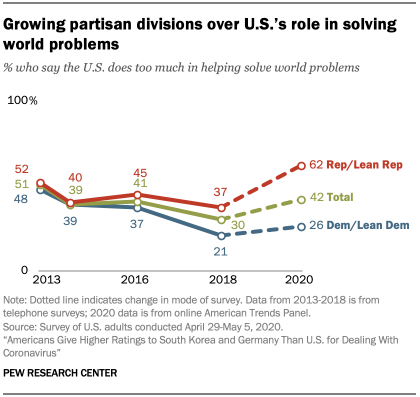

The new national survey by Pew Research Center, conducted April 29 to May 5, 2020, among 10,957 U.S. adults using the Center’s American Trends Panel, also highlights growing partisan divisions on broad questions about America’s role on the world stage.

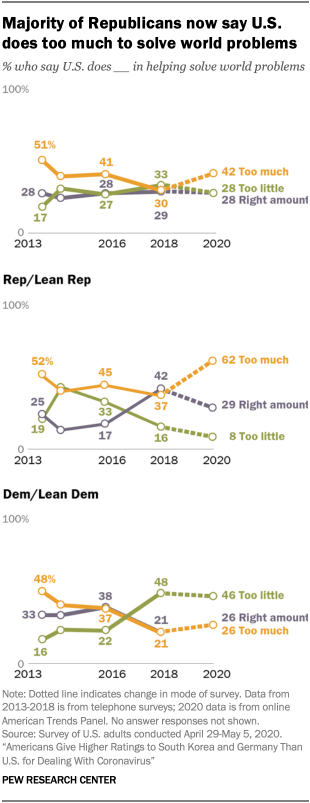

About six-in-ten Republicans (62%) now think the U.S. does too much in helping address global challenges, while just 26% of Democrats share this view. In Pew Research Center telephone surveys dating back to 2013, the partisan gap in these views was far more modest.

About six-in-ten Republicans (62%) now think the U.S. does too much in helping address global challenges, while just 26% of Democrats share this view. In Pew Research Center telephone surveys dating back to 2013, the partisan gap in these views was far more modest.

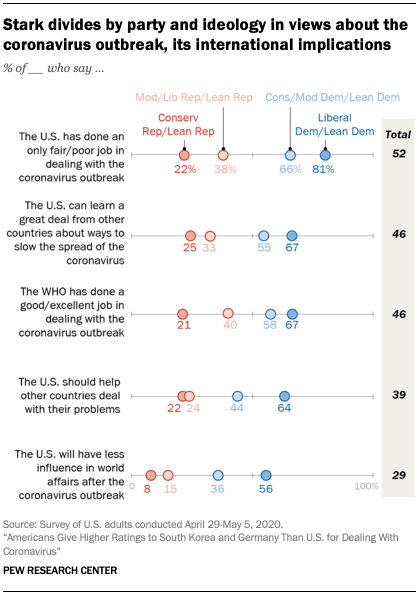

A related question about America’s role in international affairs also shows strong differences along both partisan and ideological lines. Six-in-ten Americans say the U.S. should focus on its own problems and let other countries deal with their problems as best they can; only 39% think the U.S. should help other countries deal with their problems. However, fully 64% of liberal Democrats believe the U.S. should help other countries. This is significantly higher than the 44% registered among moderate and conservative Democrats, and nearly triple the shares of moderate and liberal Republicans and conservative Republicans who hold this view.

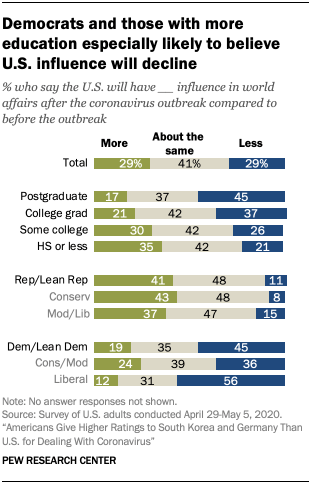

There are sharp partisan and ideological differences on other questions about foreign policy and international affairs included in the survey. While 81% of liberal Democrats think the U.S. has done an only fair or poor job of dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, just 22% of conservative Republicans say the same. Liberal Democrats stand apart for their bleak assessment of how the pandemic will affect America’s standing on the global stage: 56% believe the U.S. will have less influence in world affairs, 20 percentage points higher than the share of moderate and conservative Democrats who say this (just 15% of moderate and liberal Republicans and 8% of conservative Republicans say the U.S. will have less influence).

There are sharp partisan and ideological differences on other questions about foreign policy and international affairs included in the survey. While 81% of liberal Democrats think the U.S. has done an only fair or poor job of dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, just 22% of conservative Republicans say the same. Liberal Democrats stand apart for their bleak assessment of how the pandemic will affect America’s standing on the global stage: 56% believe the U.S. will have less influence in world affairs, 20 percentage points higher than the share of moderate and conservative Democrats who say this (just 15% of moderate and liberal Republicans and 8% of conservative Republicans say the U.S. will have less influence).

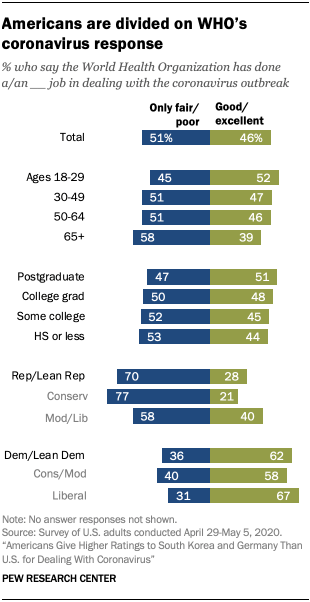

Meanwhile, conservative Republicans stand out for their especially negative evaluations of the WHO: Only 21% believe the Geneva-based organization has done an excellent or good job of dealing with the COVID-19 crisis, compared with 40% of moderate and liberal Republicans. Solid majorities of liberal Democrats (67%) and moderate and conservative Democrats (58%) give the WHO positive reviews.

Even though the belief that the U.S. can learn at least a fair amount from the rest of the world is widely shared across the political spectrum, those on the left are much more likely to think the country can learn a great deal from other nations: 67% of liberal Democrats hold this view, compared with only 25% of conservative Republicans.

In addition to partisanship, education is an important dividing line on many of the issues examined in the survey. People with higher levels of education are more likely to believe the U.S. should help other countries deal with their problems and to think the U.S. can learn from other countries about effective ways to combat coronavirus. Those with more education are also more likely to trust information from the WHO and the European Union, and to believe the U.S. will emerge from the crisis with less influence in global affairs.

How much can the U.S. learn from other countries about COVID-19?

As nations around the world grapple with how to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, most Americans think the U.S. can learn from other countries about how to limit the spread of the coronavirus.

More than eight-in-ten Americans say the U.S. can learn either a great deal or a fair amount from other countries about ways to slow the spread of the coronavirus. By comparison, fewer than two-in-ten say the U.S. can learn not too much or nothing at all from other countries.

More than eight-in-ten Americans say the U.S. can learn either a great deal or a fair amount from other countries about ways to slow the spread of the coronavirus. By comparison, fewer than two-in-ten say the U.S. can learn not too much or nothing at all from other countries.

However, there are significant partisan differences over how much the U.S. can learn from the international response. While 60% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say the U.S. can learn a great deal, just 28% of Republicans and Republican leaners share that view.

There also are differences in views on this question by race and ethnicity, as well as by level of educational attainment. Black and Hispanic people are more likely than white people to say the U.S. can learn a great deal from other nations about ways to slow the spread of the coronavirus. And the belief that the U.S. can learn from other countries about COVID-19 is more widespread among Americans with higher levels of education than among those with lower education levels.

Views on U.S. global engagement

In the current survey, conducted online among members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel, 42% of Americans say the U.S. does too much to help solve world problems, compared with smaller shares who say it does too little (28%) or the right amount (28%).

In the current survey, conducted online among members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel, 42% of Americans say the U.S. does too much to help solve world problems, compared with smaller shares who say it does too little (28%) or the right amount (28%).

In a telephone survey conducted in May 2018, the public was roughly split in their views: 30% said the U.S. did too much, 33% said it did too little and 29% said it did about the right amount. (Note: The current survey is comparable to past telephone surveys, though asking questions online can elicit somewhat different response patterns, including lower shares expressing no response on web surveys.)

A majority of Republicans (62%) now think the U.S. does too much to help solve world problems, compared with just 8% who say it does too little and 29% who say it does the right amount. On the other hand, a plurality of Democrats (48%) say the U.S. does too little to help solve world problems, while 26% each say it does the right amount or too much.

In telephone surveys in previous years, the partisan divide in these views was far less pronounced than it is today.

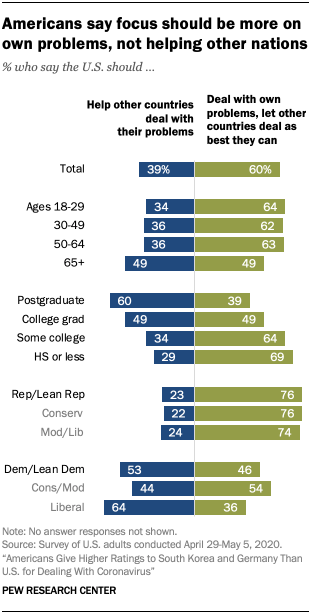

On a related measure about America’s role in the world, 60% say the U.S. should deal with its own problems and let other countries deal with their own problems as best they can. A smaller share (39%) says the U.S. should help other countries deal with their problems. Overall views are similar to those measured in a telephone survey in October 2016.

On a related measure about America’s role in the world, 60% say the U.S. should deal with its own problems and let other countries deal with their own problems as best they can. A smaller share (39%) says the U.S. should help other countries deal with their problems. Overall views are similar to those measured in a telephone survey in October 2016.

About three-quarters of Republicans want the U.S. to deal with its own problems and let other countries manage as best they can. Among Republicans, similar shares of conservatives and those who identify as more moderate or liberal take this view.

By contrast, more than half of Democrats say the U.S. should help other countries deal with their problems; 46% say the U.S. should deal with its own problems and not help with the problems of other countries. There is a divide in views among Democrats by ideology: 64% of liberal Democrats say the U.S. should help other countries deal with their problems, compared with 44% of conservative and moderate Democrats.

Those with higher levels of education are more supportive of helping other nations deal with their problems. Six-in-ten postgraduates say the U.S. should help other countries deal with their problems. College graduates are evenly split on this question, while clear majorities of those with some college experience and those with no more than a high school diploma say the U.S. should deal with its own problems.

Americans divided along party lines over how well the U.S. has done dealing with the outbreak

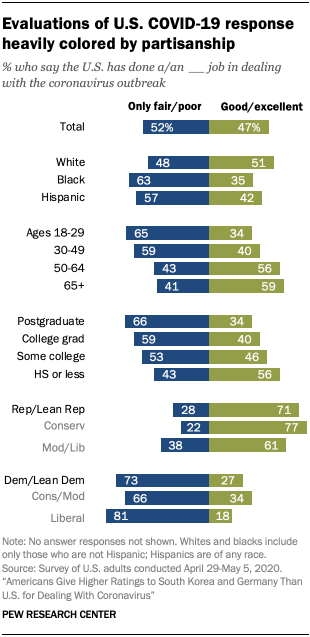

By a slim margin, more Americans say the U.S. has done only a fair or a poor job (52%) in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak than say it has done an excellent or good job (47%).

By a slim margin, more Americans say the U.S. has done only a fair or a poor job (52%) in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak than say it has done an excellent or good job (47%).

Younger adults are considerably more likely to say the U.S. has handled the outbreak poorly than older ones. Around two-thirds of those under 30 (65%) say the U.S. has done a poor job, compared with 59% of those ages 30 to 49 and only around four-in-ten of those 50 and older.

More educated Americans are also more critical of how the U.S. has dealt with the disease. Around two-thirds of those with a postgraduate degree say the U.S. has done a poor job, as do around six-in-ten college graduates. In comparison, about four-in-ten of those with a high school degree or less (43%) say the same.

Black (63%) and Hispanic (57%) Americans also rate the U.S. response more negatively than white, non-Hispanic Americans (48%).

But opinions of how well the U.S. is doing in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak are most divided along party lines. Whereas around three-quarters of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are critical of the U.S.’s response (73%), similar shares of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents praise the country’s handling of the outbreak (71%). Evaluations divide further along ideological lines, with liberal Democrats holding more negative views of the U.S.’s performance than moderate or conservative Democrats (81% vs. 66%, respectively) and conservative Republicans praising the country’s response more than moderate or liberal Republicans (77% vs. 61%).

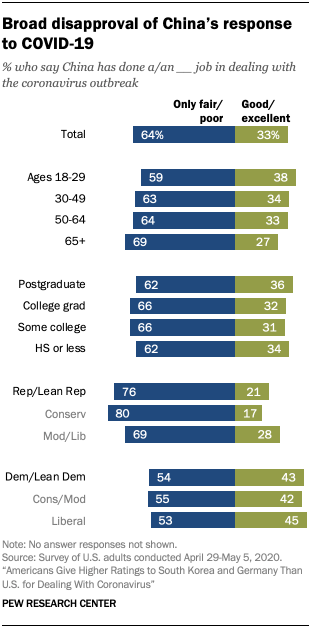

Majority of Americans are critical of China’s handling of the virus

Nearly two-thirds of Americans say China has not done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, including 37% who say the country has done a poor job.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans say China has not done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, including 37% who say the country has done a poor job.

Around six-in-ten or more in every age group are critical of China’s performance. But older Americans – who tend to have less favorable attitudes toward China – give it the lowest marks; 69% of those ages 65 and older say the country has done a fair or poor job, compared with 59% of those under 30.

Education plays little role in how people feel about China’s handling of the virus. Rather, majorities of people in all educational groups say China has not handled the pandemic well.

There are significant partisan differences on this question. While half or more of people on both sides of the aisle say China has not done a good job dealing with the outbreak, Republicans are much more likely to hold this view than Democrats. Conservative Republicans are particularly likely to say China has not handled the crisis well: Eight-in-ten hold this view.

Partisanship and international orientation are factors in how Americans think other countries have handled the outbreak

Whereas evaluations of both the United States’ and China’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak are quite partisan, this is less the case when it comes to the other four countries asked about in the survey. Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say Italy, South Korea and Germany have handled the outbreak well. But, in each of these instances, the difference is less than 10 percentage points. In the case of the UK, 54% of Republicans say the country has done an excellent or good job, compared with 45% of Democrats.

Whereas evaluations of both the United States’ and China’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak are quite partisan, this is less the case when it comes to the other four countries asked about in the survey. Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say Italy, South Korea and Germany have handled the outbreak well. But, in each of these instances, the difference is less than 10 percentage points. In the case of the UK, 54% of Republicans say the country has done an excellent or good job, compared with 45% of Democrats.

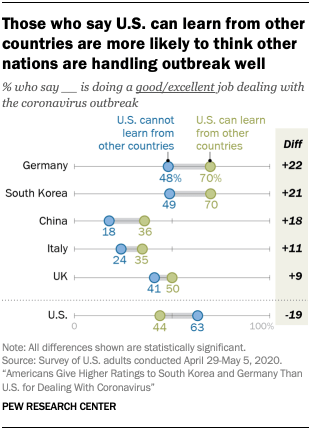

Americans who believe the U.S. can learn a great deal or a fair amount from other countries about ways to slow the spread of coronavirus are especially likely to say other countries are handling the outbreak well. The differences are most pronounced when it comes to Germany and South Korea. For example, 70% of those who say the U.S. can learn from other countries say Germany is handling the coronavirus outbreak well, compared with 48% of those who think that the U.S. can learn little or nothing from other countries.

Republicans who believe the U.S. can learn from other nations are more likely than other Republicans to say other countries are dealing with the pandemic effectively. And the same pattern is found among Democrats.

Republicans who believe the U.S. can learn from other nations are more likely than other Republicans to say other countries are dealing with the pandemic effectively. And the same pattern is found among Democrats.

When it comes to assessments of how well the U.S. is dealing with the outbreak, those who think the U.S. can learn from foreign countries tend to evaluate its current handling of the pandemic less positively. Fewer than half (44%) of those who think the U.S. can glean information from abroad say the country is doing an excellent or good job handling the outbreak, compared with 63% of those who say the U.S. can’t learn much from overseas.

Partisans divided in their assessments of the WHO

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been a key player in addressing the global spread of the coronavirus, which the organization characterized as a pandemic in early March. But the organization has been heavily criticized by President Donald Trump in recent weeks. In mid-April, he halted U.S. funding of the organization – a move sharply criticized by top Democrats.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been a key player in addressing the global spread of the coronavirus, which the organization characterized as a pandemic in early March. But the organization has been heavily criticized by President Donald Trump in recent weeks. In mid-April, he halted U.S. funding of the organization – a move sharply criticized by top Democrats.

Americans’ views of how well the WHO has dealt with the coronavirus outbreak also fall along partisan lines. Whereas 62% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say the organization has done at least a good job in handling the global pandemic, only 28% of Republicans and GOP leaners say the same. Conservative Republicans are less likely to applaud the organization’s handling of the virus than moderate or liberal Republicans.

Americans with a postgraduate education are somewhat more likely than those with less education to applaud the international organization’s handling of the outbreak, though the differences are muted. Younger Americans also approve of the WHO’s performance more than older Americans: 52% of adults under age 30 say it has done excellent or good job, compared with just 39% of those 65 and older.

Information about coronavirus from EU, WHO generally viewed as trustworthy, but most do not trust information from Chinese government

As Americans receive information about the coronavirus outbreak from various international sources, majorities say they trust data from the European Union and WHO, but most are wary of information coming from the Chinese government. Only 15% of U.S. adults say they trust information from Beijing at least a fair amount.

As Americans receive information about the coronavirus outbreak from various international sources, majorities say they trust data from the European Union and WHO, but most are wary of information coming from the Chinese government. Only 15% of U.S. adults say they trust information from Beijing at least a fair amount.

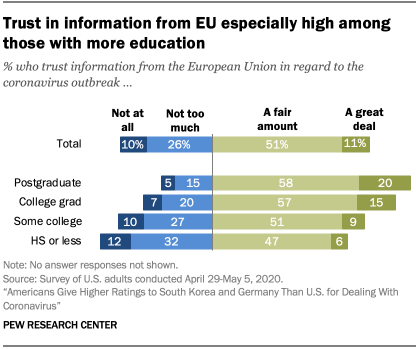

Trust in information from the EU and WHO, while relatively high overall, is even stronger among people with a college degree or higher. About three-quarters of Americans with a postgraduate degree (78%) or college degree (72%) say they can believe information coming from the EU about the coronavirus outbreak.

Trust in information from the EU and WHO, while relatively high overall, is even stronger among people with a college degree or higher. About three-quarters of Americans with a postgraduate degree (78%) or college degree (72%) say they can believe information coming from the EU about the coronavirus outbreak.

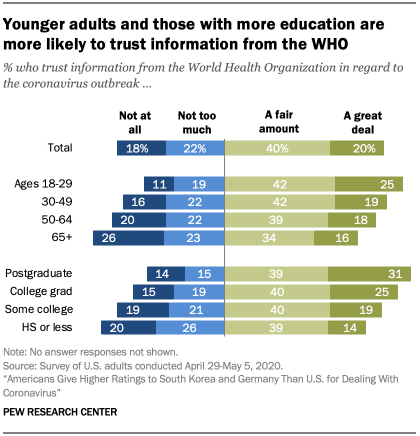

Similarly, 70% of people with a postgraduate degree trust information from the WHO at least a fair amount, including roughly one-third who say they trust the WHO a great deal when it comes to information about the coronavirus. About half of people with a high school degree say they trust information from this source.

Younger adults are also more likely to view information from the WHO as trustworthy; 68% of Americans ages 18 to 29 say they can trust information from the WHO at least a fair amount. Only about half of adults ages 65 and older (51%) share this view.

Younger adults are also more likely to view information from the WHO as trustworthy; 68% of Americans ages 18 to 29 say they can trust information from the WHO at least a fair amount. Only about half of adults ages 65 and older (51%) share this view.

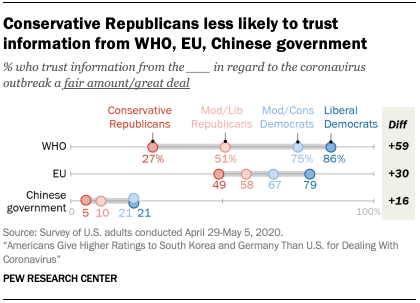

Differences by education and age, however, are relatively small compared with the substantial partisan division in these views. Conservative Republicans are much less likely than liberal Democrats to trust information coming from each international source.

This partisan divide is especially pronounced on views about the WHO; 86% of liberal Democrats say they trust information from the WHO at least a fair amount, compared with 27% of conservative Republicans. Similar, though somewhat smaller, divisions also exist in trust in information from the EU and the Chinese government.

This partisan divide is especially pronounced on views about the WHO; 86% of liberal Democrats say they trust information from the WHO at least a fair amount, compared with 27% of conservative Republicans. Similar, though somewhat smaller, divisions also exist in trust in information from the EU and the Chinese government.

How will the pandemic affect the international standing of the U.S., China and the EU?

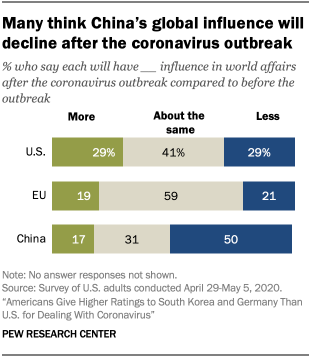

While half of Americans believe China will emerge from the current crisis with less influence in world affairs, far fewer say this about the U.S. or the European Union.

While half of Americans believe China will emerge from the current crisis with less influence in world affairs, far fewer say this about the U.S. or the European Union.

The American public is largely split on how they think U.S. influence will be affected by the pandemic. Roughly three-in-ten believe the U.S.’s international clout will be bolstered after the outbreak, while the same share thinks it will be weakened. About four-in-ten see the U.S. coming out of the outbreak with the same influence as before.

Clear partisan gaps emerge on this question. Republicans are about twice as likely as Democrats to believe the U.S.’s international influence will be strengthened as a result of the crisis. On the other hand, Democrats are about four times more likely than Republicans to expect American influence to weaken after the outbreak. There is also internal division among Democrats on this question, with liberal party supporters 20 percentage points more likely than conservatives and moderates within the party to foresee the decline of U.S. international influence.

Clear partisan gaps emerge on this question. Republicans are about twice as likely as Democrats to believe the U.S.’s international influence will be strengthened as a result of the crisis. On the other hand, Democrats are about four times more likely than Republicans to expect American influence to weaken after the outbreak. There is also internal division among Democrats on this question, with liberal party supporters 20 percentage points more likely than conservatives and moderates within the party to foresee the decline of U.S. international influence.

Education is also tied to views about how the pandemic will shape America’s role in international affairs. In general, Americans who have completed higher levels of education are more likely to think the country’s global influence will recede. For example, 45% of those with postgraduate degrees think the U.S.’s global position will decline after the pandemic, compared with just 21% of those with a high school diploma or less.

Education is also tied to views about how the pandemic will shape America’s role in international affairs. In general, Americans who have completed higher levels of education are more likely to think the country’s global influence will recede. For example, 45% of those with postgraduate degrees think the U.S.’s global position will decline after the pandemic, compared with just 21% of those with a high school diploma or less.

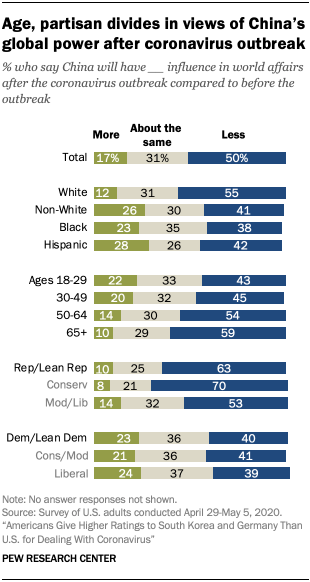

When asked about China’s influence on the world stage, half of Americans believe it will decline after the coronavirus outbreak. Nearly one-in-five think Chinese influence will grow, and about a third think its global standing will be about the same.

There is a large partisan divide on this question: Roughly six-in-ten Republicans believe China’s international clout will diminish as a result of the coronavirus outbreak, while just 40% of Democrats say the same. Age divides emerge on this question as well. American adults ages 65 and older are 16 percentage points more likely than those under 30 to say China will have less global influence after the crisis.

These partisan and age divides are similar to other attitudes about China. Older Americans and Republicans are also especially likely to say they have a negative opinion of China.

These partisan and age divides are similar to other attitudes about China. Older Americans and Republicans are also especially likely to say they have a negative opinion of China.

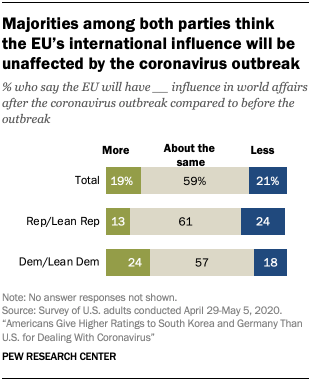

On views of the future international role of the European Union, a sizable majority of Americans believe the EU’s global standing will be unaffected by the crisis, while about a fifth believe it will increase or decrease, respectively.

There is a partisan divide on this question as well, with Republicans less likely than Democrats to think the EU will have more influence.