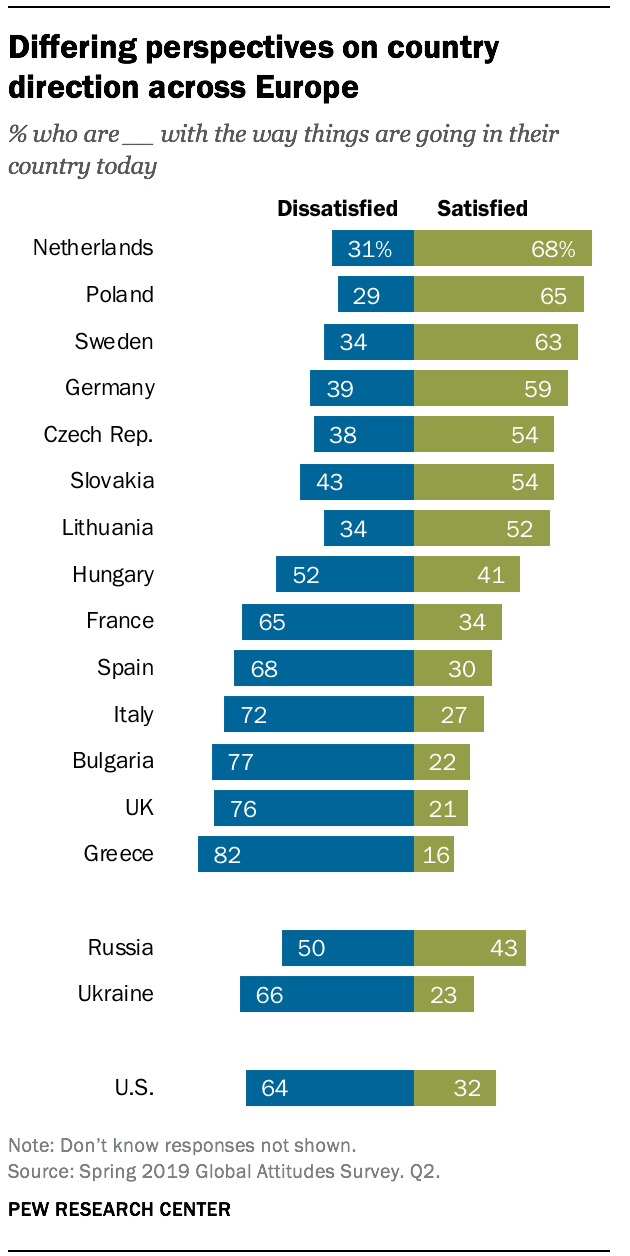

Half or more say they are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country today in nine of the countries surveyed, a pattern that is mirrored in the U.S. In Greece, Bulgaria and the UK, about three-quarters or more are dissatisfied with the direction of their country, and roughly two-thirds or more are similarly dissatisfied in Italy, Spain and France.

Half or more say they are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country today in nine of the countries surveyed, a pattern that is mirrored in the U.S. In Greece, Bulgaria and the UK, about three-quarters or more are dissatisfied with the direction of their country, and roughly two-thirds or more are similarly dissatisfied in Italy, Spain and France.

In the former Soviet republics of Russia and Ukraine, 50% and 66% are dissatisfied, respectively.

In contrast, roughly two-thirds in the Netherlands and Poland and majorities in Sweden and Germany are satisfied with the direction of the country today.

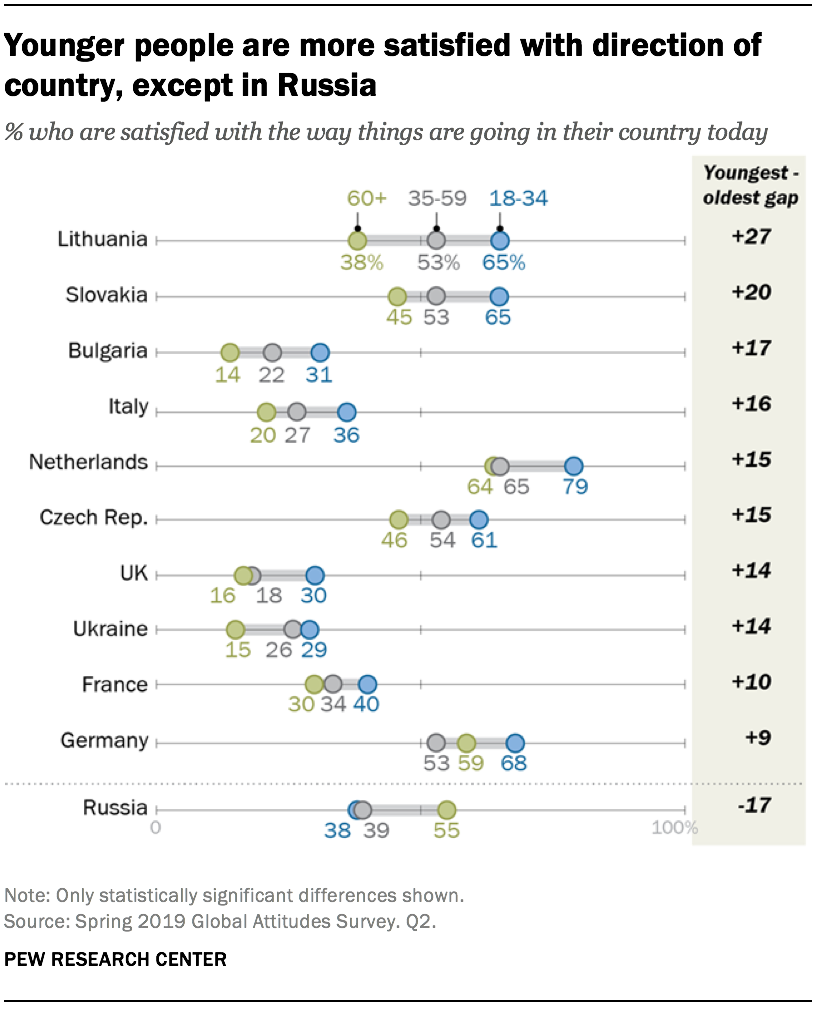

In most European countries, those ages 18 to 34 are more satisfied with the direction of their country than those 60 and older. As an example, younger Lithuanians are 27 percentage points more satisfied with the direction of their country than those over 60. In Russia, however, the pattern is reversed: Russians 60 and older are more satisfied with the way things are going in their country than their younger counterparts.

In most European countries, those ages 18 to 34 are more satisfied with the direction of their country than those 60 and older. As an example, younger Lithuanians are 27 percentage points more satisfied with the direction of their country than those over 60. In Russia, however, the pattern is reversed: Russians 60 and older are more satisfied with the way things are going in their country than their younger counterparts.

Similarly, in most countries, those with more education, people with higher incomes and supporters of their country’s governing party are more satisfied with the direction of their country.

Those living in areas corresponding to pre-1990 West Germany (61%) are more satisfied with the country’s direction than those living in former East Germany (50%).

Unlike in previous years, many Europeans say the current economic situation is good

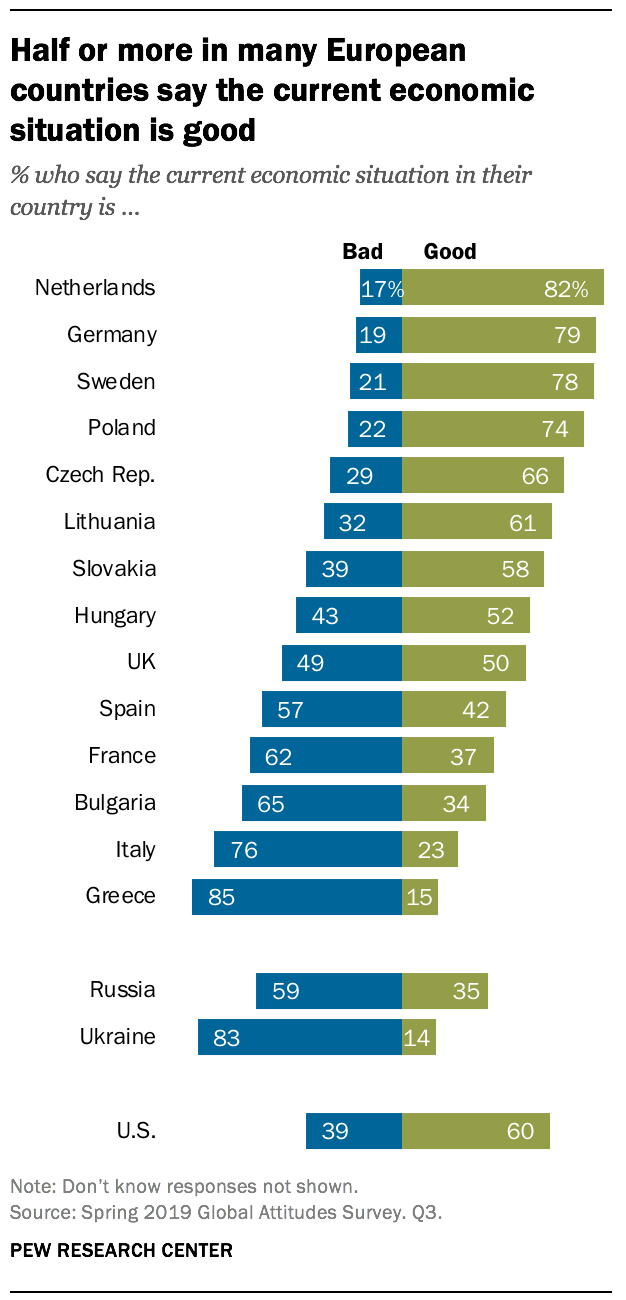

Around half or more say the current economic situation is good in nine of the 16 European countries surveyed. Roughly three-quarters or more describe the current economic situation as good in the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and Poland. U.S. views of the economic situation are also positive.

Around half or more say the current economic situation is good in nine of the 16 European countries surveyed. Roughly three-quarters or more describe the current economic situation as good in the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and Poland. U.S. views of the economic situation are also positive.

However, around three-quarters or more in Greece and Italy describe the current economic situation as bad. Publics in Russia and Ukraine agree with this sentiment. Roughly four-in-ten Ukrainians (39%) even describe the current economic situation as very bad.

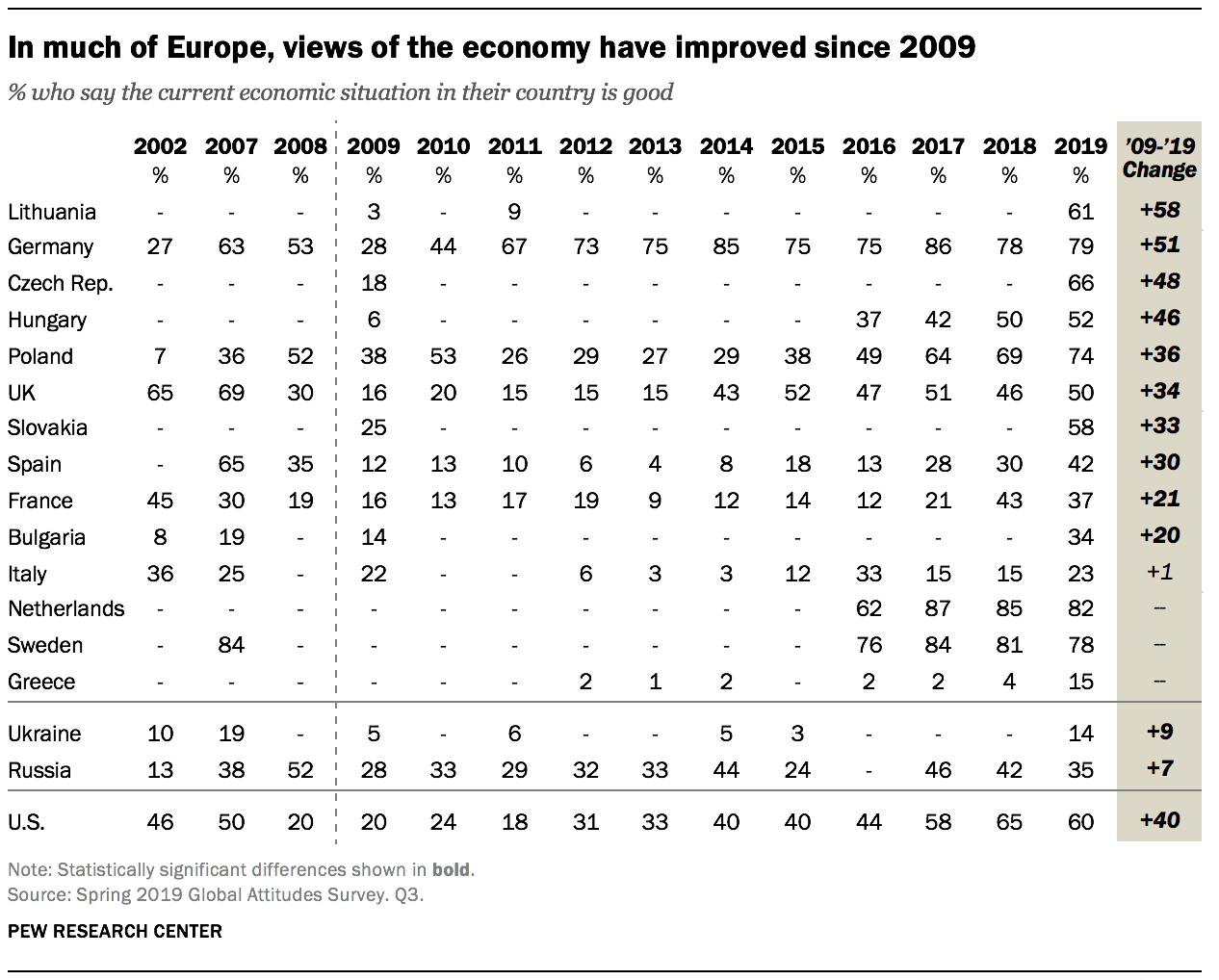

Since the global economic crisis of 2009, evaluations of the economic situation have grown rosier in most countries. Larger shares describe the economic situation as good today than in 2009 in 13 of 14 countries polled in both years. This includes a 58 percentage point increase in Lithuania and a 51-point jump in Germany. In Italy, there has been no significant change.

Those with more education are more likely to describe the current economic situation as good in most countries. For instance, in France, 50% of people with a postsecondary education or more say the economic situation is good, compared with only 32% among those with less education. In Russia, however, those with less education are more likely to describe the economic situation as good.

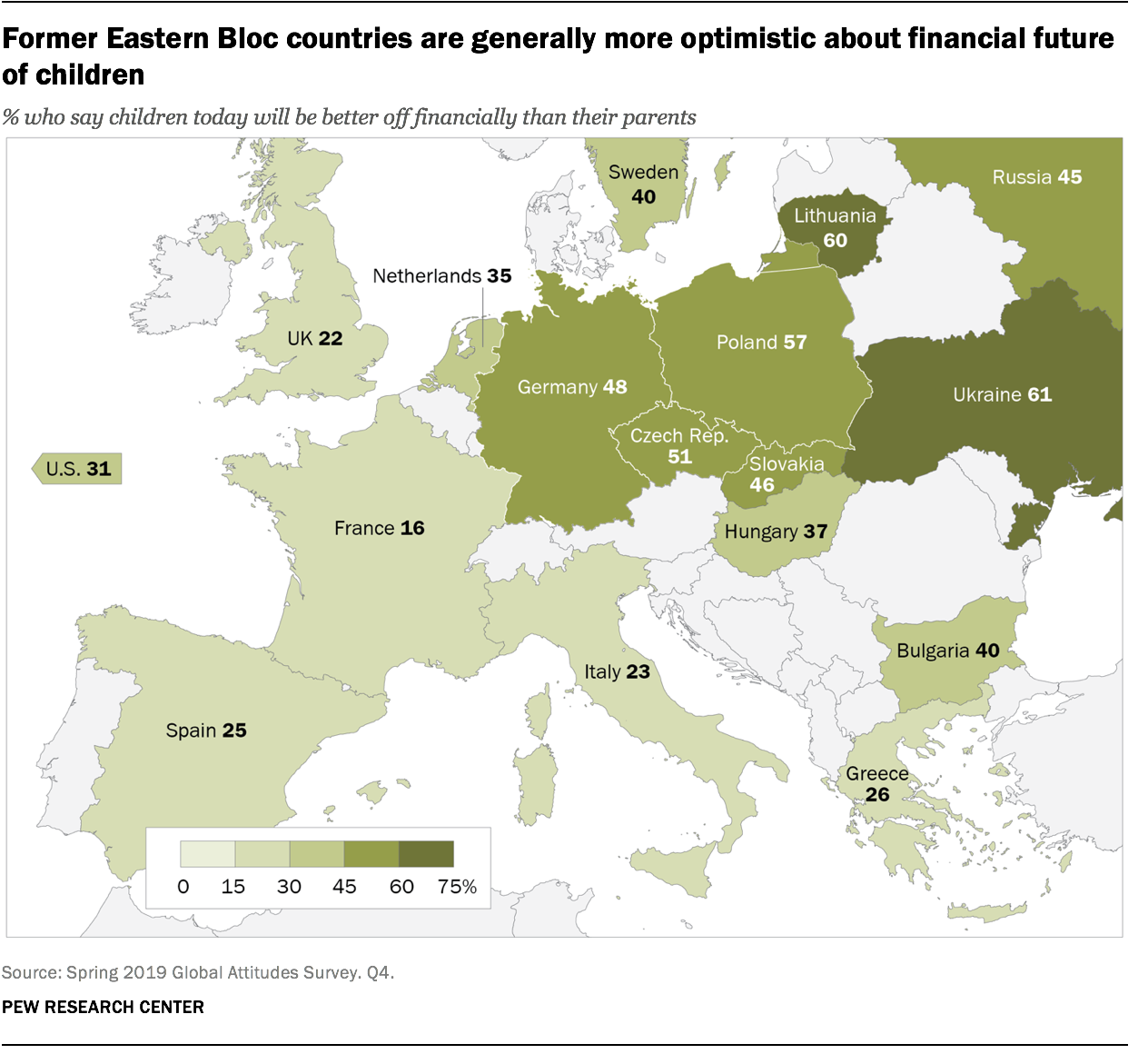

Regional differences about whether children will be better off financially than their parents

By and large, publics in Central and Eastern Europe as well as in former Soviet republics are more optimistic about the financial future of children today than Western Europeans and Americans. Roughly six-in-ten Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Poles say children today will be better off financially than their parents. On the other end of the spectrum, about one-quarter of Greeks, Spaniards, Italians and Britons, along with 16% of the French, share this optimism.

Of the countries surveyed in both 2013 and 2019, shares who say children today will be better off financially than their parents have greatly increased in Poland (+31 percentage points) and Germany (+20 points), while Italy (+9) and France (+7) have seen modest upticks. Ukrainians, who were first asked this question in 2014, have also seen a 10-point increase in those saying children will be better off. Opinion has not significantly changed in the other countries.

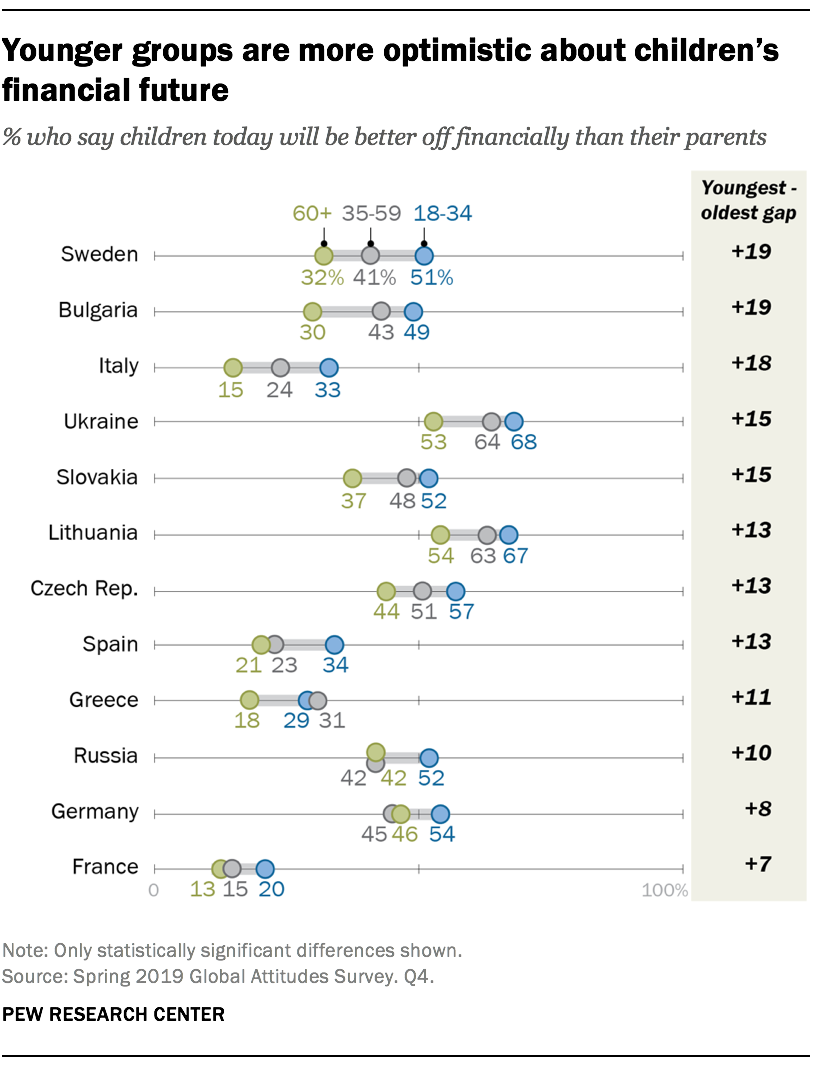

In a majority of countries, those ages 18 to 34 are more positive about the financial future of children than those ages 60 and older. In Sweden and Bulgaria, this gap is 19 percentage points.

In a majority of countries, those ages 18 to 34 are more positive about the financial future of children than those ages 60 and older. In Sweden and Bulgaria, this gap is 19 percentage points.

Those who support the governing party are more optimistic about the financial status of children than those who do not support the governing party.

In most countries, those with lower incomes are more likely to say that when children today grow up, they will be worse off financially than their parents.

Life satisfaction has improved for Europeans

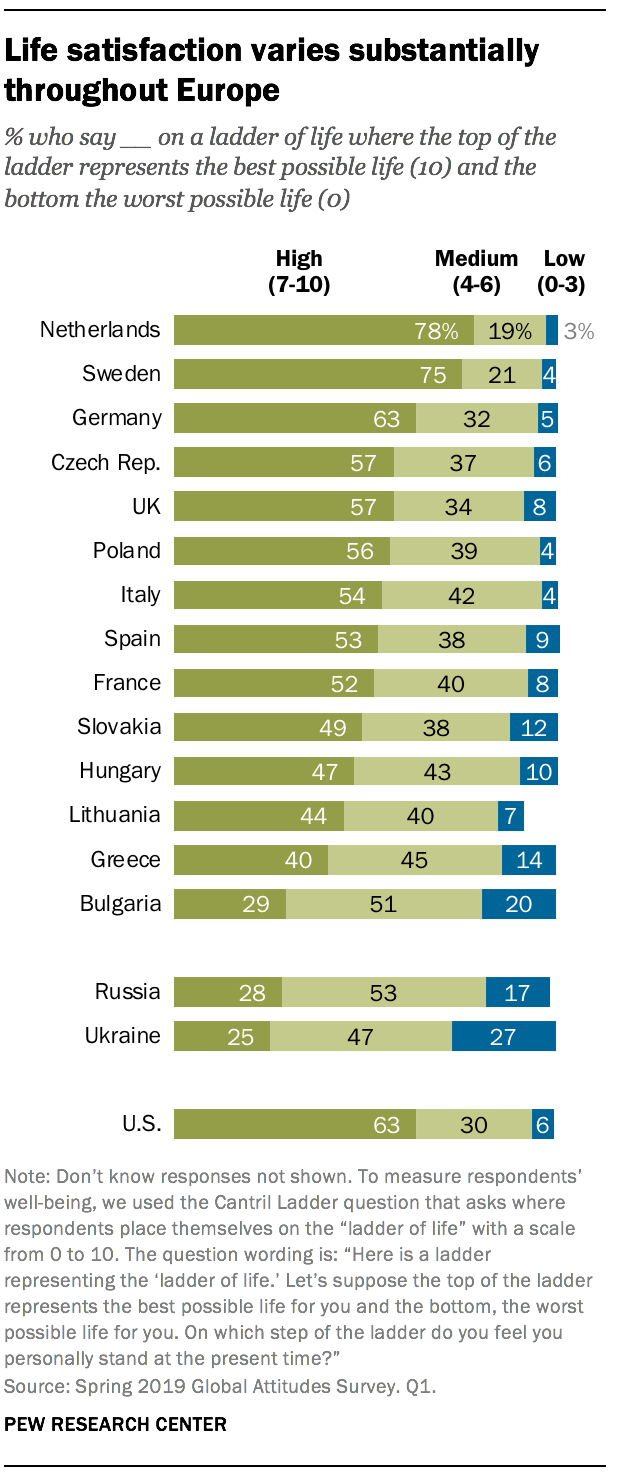

Most Europeans are relatively satisfied with their lives. More than half in nine of the 16 countries surveyed place themselves as a 7, 8, 9 or 10 on a ladder of life, where the top of the ladder represents the best possible life. Three-quarters or more place themselves on the top rungs of the ladder in the Netherlands and Sweden, while only one-quarter say the same in Ukraine.

Most Europeans are relatively satisfied with their lives. More than half in nine of the 16 countries surveyed place themselves as a 7, 8, 9 or 10 on a ladder of life, where the top of the ladder represents the best possible life. Three-quarters or more place themselves on the top rungs of the ladder in the Netherlands and Sweden, while only one-quarter say the same in Ukraine.

As has been found in previous Pew Research Center analyses, life satisfaction continues to be strongly related with economic factors. For example, the Netherlands has the highest per capita income of the European countries surveyed, and 78% of the Dutch say their life is a 7 or higher on a 0-10 scale. On the other end of the spectrum, Ukrainians have the lowest national income per capita and the lowest share who rate their quality of life highly.

Life satisfaction is also strongly associated with positive views about the nation’s economic situation.

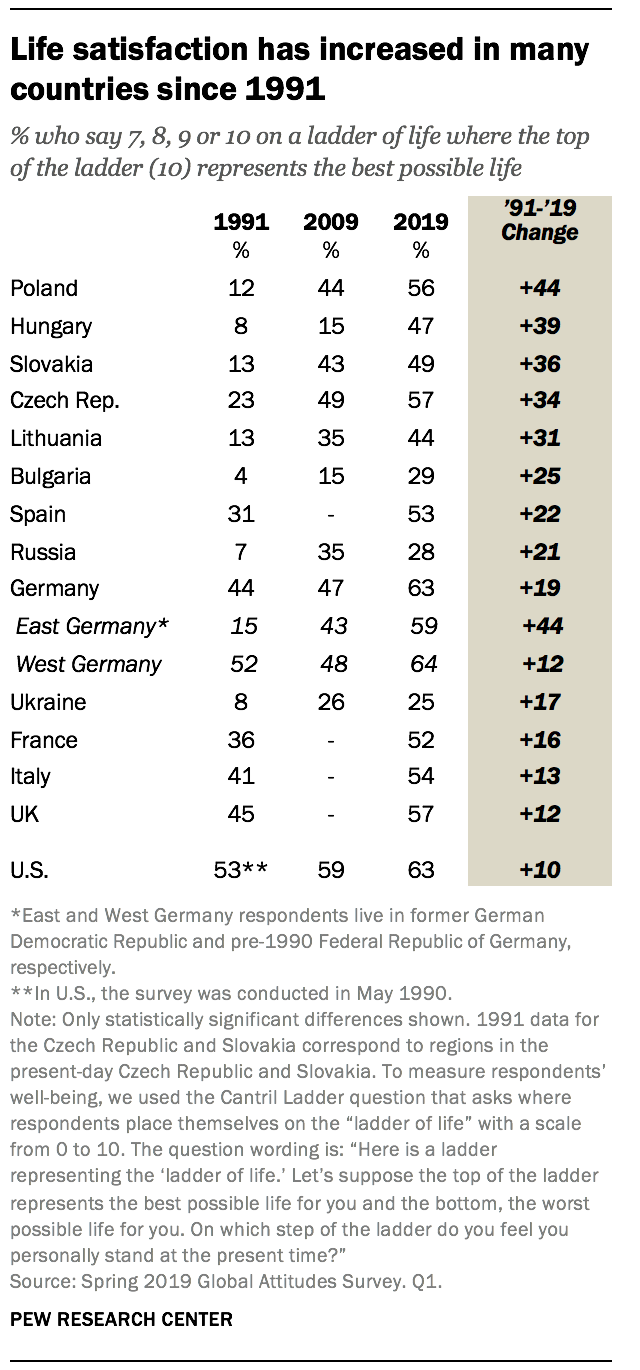

In all countries originally surveyed in 1991, life satisfaction has improved, sometimes dramatically. The largest changes have occurred in Central and Eastern European countries such as Poland, where the percentage of people placing themselves as a 7 or higher on the ladder of life has increased by 44 percentage points since 1991. Whereas only 12% of Poles rated themselves highly nearly 30 years ago, now 56% do so.

In all countries originally surveyed in 1991, life satisfaction has improved, sometimes dramatically. The largest changes have occurred in Central and Eastern European countries such as Poland, where the percentage of people placing themselves as a 7 or higher on the ladder of life has increased by 44 percentage points since 1991. Whereas only 12% of Poles rated themselves highly nearly 30 years ago, now 56% do so.

Those who live in former East Germany have also experienced a considerable increase in life satisfaction. In 1991, only 15% of East Germans rated their life highly; today around six-in-ten say their life is a 7 or higher on the ladder of life. West Germans – those in pre-1990 Federal Republic of Germany – have also seen an increase in the share who rate their life highly (+12 percentage points).

In the three former Soviet republics surveyed, life satisfaction has improved, but fewer than half place themselves high on the ladder of life. Russians are 21 percentage points more likely to rate themselves highly in 2019 than in 1991. Despite this improvement, though, only around one-quarter of Russians say they are a 7 or higher on the ladder today. Russians were the only group to see a significant decline in life satisfaction from 2009 to 2019: More Russians placed themselves highly on the ladder of life in 2009 than in 2019 (35% vs. 28%).

Younger populations, those ages 18 to 34, rate themselves higher on life satisfaction than older populations, those ages 60 and older, in 13 of the 16 European countries surveyed. Those with more education and higher incomes are also more likely to say that their quality of life is a 7 or higher in all countries.

Europeans generally agree success in life is determined by forces outside their control

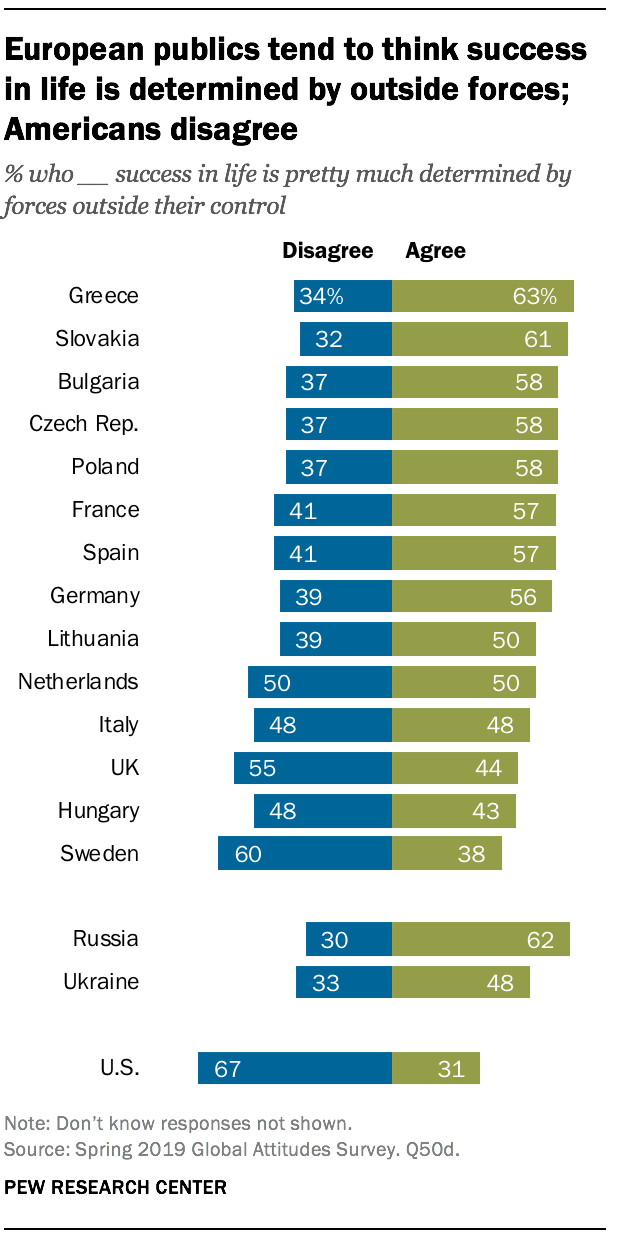

When it comes to whether success in life is determined by forces outside their control, publics across Europe are largely in agreement. Around half or more agree success in life is determined by outside forces in most of the countries surveyed. The UK and Sweden are the exceptions, with majorities disagreeing that success is determined by forces outside their control. These publics are like that of the U.S., where two-thirds disagree with the statement.

When it comes to whether success in life is determined by forces outside their control, publics across Europe are largely in agreement. Around half or more agree success in life is determined by outside forces in most of the countries surveyed. The UK and Sweden are the exceptions, with majorities disagreeing that success is determined by forces outside their control. These publics are like that of the U.S., where two-thirds disagree with the statement.

While one-quarter or more in Spain and Russia completely agree success is determined by outside forces, around three-in-ten in the U.S. and Sweden completely disagree.

In most countries surveyed, more disagree that success in life is determined by forces beyond their control today than was the case in 1991.

In most countries surveyed, more disagree that success in life is determined by forces beyond their control today than was the case in 1991.

For example, people in Bulgaria and Hungary increasingly disagree that success in life is pretty much determined by forces outside their control (+22 and +21 percentage points, respectively, since 1991). Lithuanians are 19 points more likely to disagree that success in life is determined by outside forces in 2019 than in 1991, whereas Ukrainians have seen an 8-point change over time.

Those with higher levels of education are more likely to disagree that success in life is determined by forces beyond their control in most countries.