caption id="attachment_44106" align="alignnone" width="1024"] A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from

Freedom House to the

Economist Intelligence Unit to

V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center

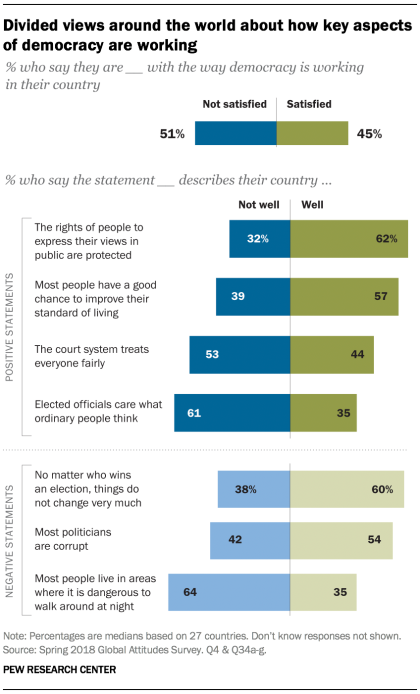

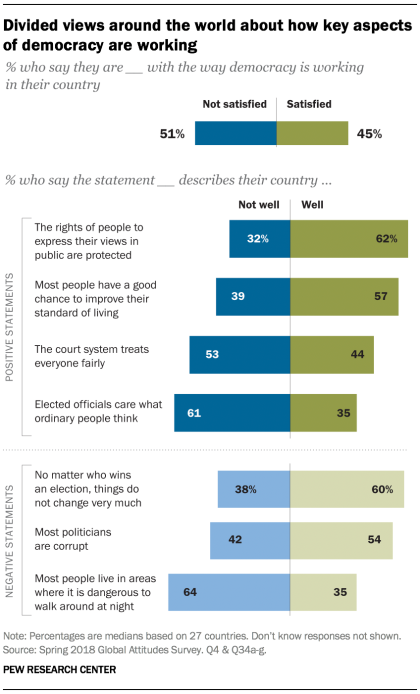

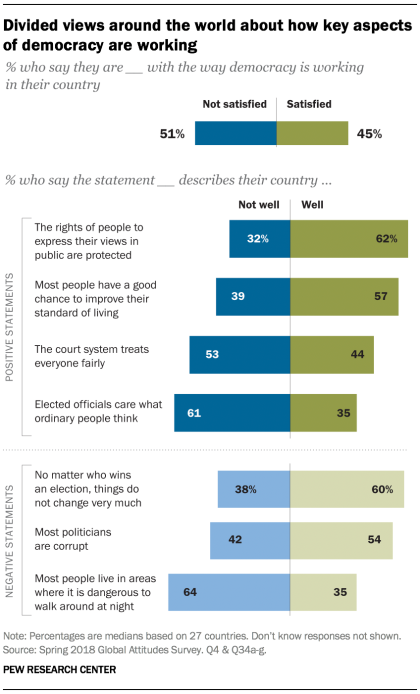

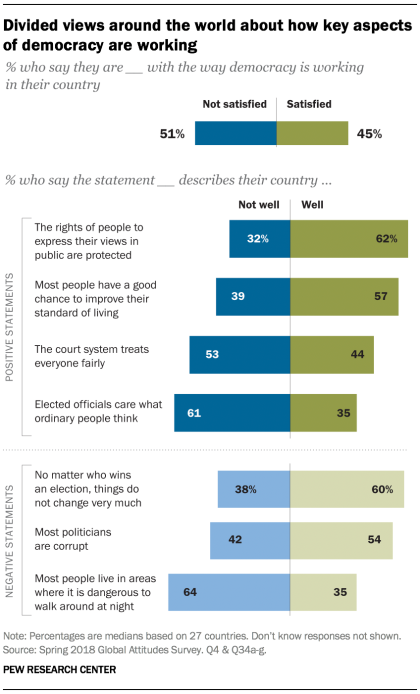

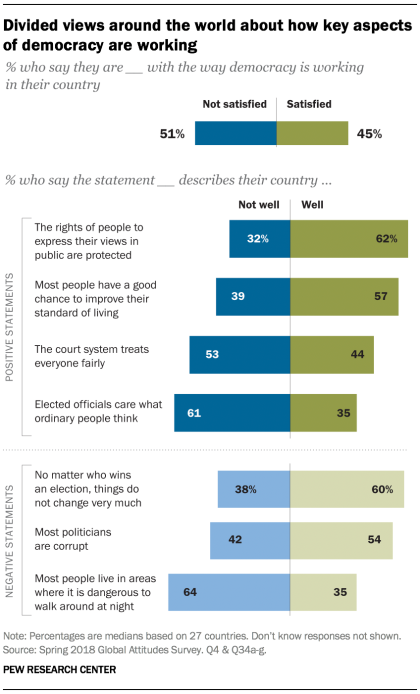

surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see

Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Measuring satisfaction, dissatisfaction with how democracy is working

We measured satisfaction with the

performance of democracy in each country using the following question: How satisfied are you with the way democracy is working in our country – very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not too satisfied, or not at all satisfied? This question is commonly used by academics and on international surveys, including the

Global Barometer Surveys.

Satisfaction with democracy can be thought of as one measure of popular contentment – with the current regime in power or the direction of the nation.

1 For example,

results of this survey and work by other researchers show that people who support the party or coalition in power (the “winners”) tend to be more satisfied than others.

2

The question does not take into account institutional or other features that are sometimes used to characterize a democracy’s health. For example,

our findings do not necessarily mirror ratings found in the

Democracy Index, developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit, or Freedom House’s

Freedom Ratings.

The satisfaction question also does not measure attitudes toward democratic values or belief in the principles of liberal democracy. That said, scholars have explored the link between views of how democracy is working and commitment to democratic principles. For example, one group of researchers found that across 54 countries, satisfaction with democracy was one of the key factors affecting people’s normative commitment to democracy.

3 Our data, too, indicates that the more dissatisfied people are with democracy, the less likely they are to say representative democracy, rather than alternative models like technocracy, a strong leader model, or military rule, is a good way to govern their country (for more on this,

see Chapter 1).

Some scholars also use the question about democracy’s performance to identify “dissatisfied democrats” – those committed to democratic institutions but dissatisfied with the current state of democracy in their country – a group some argue is important for preventing democracies from “back-sliding” into authoritarian regimes.

4

1 Linde, Jonas, and Joakim Ekman. 2003. “

Satisfaction with democracy: A note on a frequently used indicator in comparative politics.” European Journal of Political Research.

2 Wells, Jason M., and Jonathan Krieckhaus. 2006. “

Does National Context Influence Democratic Satisfaction? A Multi-level Analysis.” Political Research Quarterly.

3 Chu, Yu-ham, Michael Bratton, Marta Lagos, Sandeep Shastri and Mark Tessler. 2008. “

Public Opinion and Democratic Legitimacy.” Journal of Democracy.

4 Norris, Pippa. Ed. 1999. “Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government.”

[/collapsible]

caption id="attachment_44106" align="alignnone" width="1024"] A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

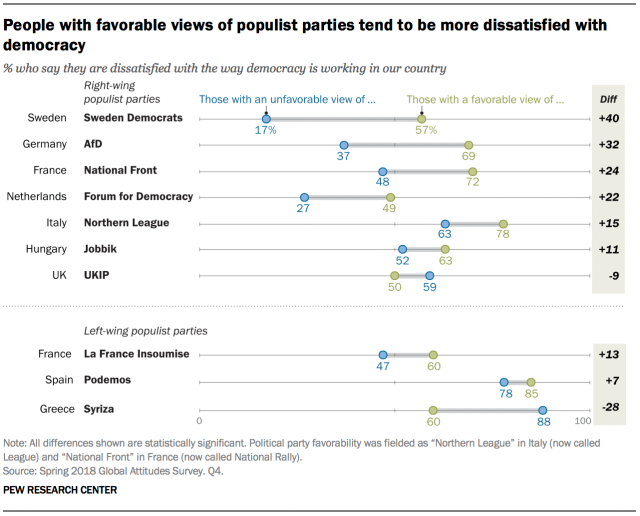

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Measuring satisfaction, dissatisfaction with how democracy is working

We measured satisfaction with the performance of democracy in each country using the following question: How satisfied are you with the way democracy is working in our country – very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not too satisfied, or not at all satisfied? This question is commonly used by academics and on international surveys, including the Global Barometer Surveys.

Satisfaction with democracy can be thought of as one measure of popular contentment – with the current regime in power or the direction of the nation.1 For example, results of this survey and work by other researchers show that people who support the party or coalition in power (the “winners”) tend to be more satisfied than others.2

The question does not take into account institutional or other features that are sometimes used to characterize a democracy’s health. For example, our findings do not necessarily mirror ratings found in the Democracy Index, developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit, or Freedom House’s Freedom Ratings.

The satisfaction question also does not measure attitudes toward democratic values or belief in the principles of liberal democracy. That said, scholars have explored the link between views of how democracy is working and commitment to democratic principles. For example, one group of researchers found that across 54 countries, satisfaction with democracy was one of the key factors affecting people’s normative commitment to democracy.3 Our data, too, indicates that the more dissatisfied people are with democracy, the less likely they are to say representative democracy, rather than alternative models like technocracy, a strong leader model, or military rule, is a good way to govern their country (for more on this, see Chapter 1).

Some scholars also use the question about democracy’s performance to identify “dissatisfied democrats” – those committed to democratic institutions but dissatisfied with the current state of democracy in their country – a group some argue is important for preventing democracies from “back-sliding” into authoritarian regimes.4

1 Linde, Jonas, and Joakim Ekman. 2003. “

Satisfaction with democracy: A note on a frequently used indicator in comparative politics.” European Journal of Political Research.

2 Wells, Jason M., and Jonathan Krieckhaus. 2006. “

Does National Context Influence Democratic Satisfaction? A Multi-level Analysis.” Political Research Quarterly.

3 Chu, Yu-ham, Michael Bratton, Marta Lagos, Sandeep Shastri and Mark Tessler. 2008. “

Public Opinion and Democratic Legitimacy.” Journal of Democracy.

4 Norris, Pippa. Ed. 1999. “Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government.”

[/collapsible]

Economic discontent and democratic dissatisfactioncaption id="attachment_44106" align="alignnone" width="1024"] A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Measuring satisfaction, dissatisfaction with how democracy is working

We measured satisfaction with the performance of democracy in each country using the following question: How satisfied are you with the way democracy is working in our country – very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not too satisfied, or not at all satisfied? This question is commonly used by academics and on international surveys, including the Global Barometer Surveys.

Satisfaction with democracy can be thought of as one measure of popular contentment – with the current regime in power or the direction of the nation.1 For example, results of this survey and work by other researchers show that people who support the party or coalition in power (the “winners”) tend to be more satisfied than others.2

The question does not take into account institutional or other features that are sometimes used to characterize a democracy’s health. For example, our findings do not necessarily mirror ratings found in the Democracy Index, developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit, or Freedom House’s Freedom Ratings.

The satisfaction question also does not measure attitudes toward democratic values or belief in the principles of liberal democracy. That said, scholars have explored the link between views of how democracy is working and commitment to democratic principles. For example, one group of researchers found that across 54 countries, satisfaction with democracy was one of the key factors affecting people’s normative commitment to democracy.3 Our data, too, indicates that the more dissatisfied people are with democracy, the less likely they are to say representative democracy, rather than alternative models like technocracy, a strong leader model, or military rule, is a good way to govern their country (for more on this, see Chapter 1).

Some scholars also use the question about democracy’s performance to identify “dissatisfied democrats” – those committed to democratic institutions but dissatisfied with the current state of democracy in their country – a group some argue is important for preventing democracies from “back-sliding” into authoritarian regimes.4

1 Linde, Jonas, and Joakim Ekman. 2003. “

Satisfaction with democracy: A note on a frequently used indicator in comparative politics.” European Journal of Political Research.

2 Wells, Jason M., and Jonathan Krieckhaus. 2006. “

Does National Context Influence Democratic Satisfaction? A Multi-level Analysis.” Political Research Quarterly.

3 Chu, Yu-ham, Michael Bratton, Marta Lagos, Sandeep Shastri and Mark Tessler. 2008. “

Public Opinion and Democratic Legitimacy.” Journal of Democracy.

4 Norris, Pippa. Ed. 1999. “Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government.”

[/collapsible]

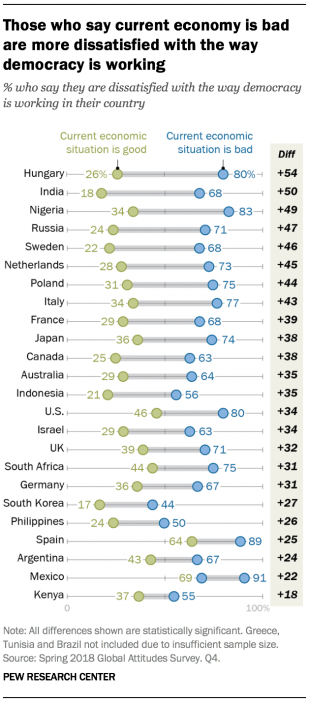

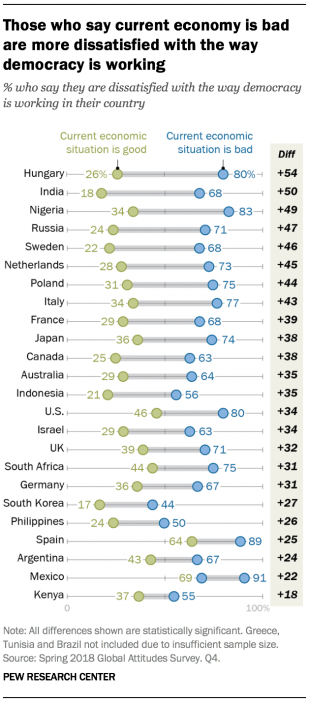

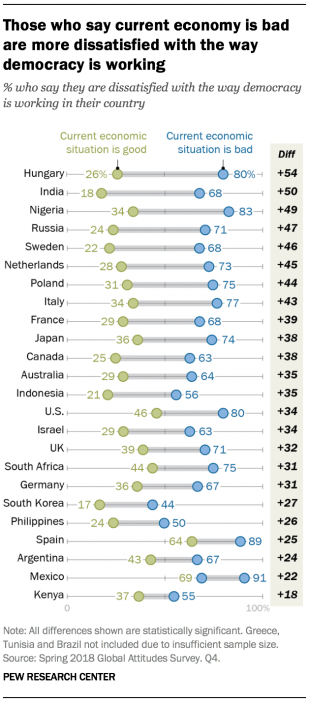

Economic discontent and democratic dissatisfaction

The link between views of the economy and assessments of democratic performance is strong. In 24 of 27 countries surveyed, people who say the national economy is in bad shape are more likely than those who say it is in good shape to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is working. In the other three countries surveyed, so few people say the economy is good that this relationship cannot be analyzed.

For example, eight-in-ten Hungarians who say the national economic situation is poor are also dissatisfied with the performance of the country’s democracy, compared with just 26% of those who believe the economic situation is good.

Views about economic opportunity also play a role. In 26 of 27 nations, those who believe their country is one in which most people cannot improve their standard of living are more likely to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is working.

However, personal income is not a major factor. And multilevel regression analysis suggests that, in general, demographic variables including gender, age and education are not strongly related to democratic dissatisfaction.

Individual rights and democratic performancecaption id="attachment_44106" align="alignnone" width="1024"] A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Measuring satisfaction, dissatisfaction with how democracy is working

We measured satisfaction with the performance of democracy in each country using the following question: How satisfied are you with the way democracy is working in our country – very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not too satisfied, or not at all satisfied? This question is commonly used by academics and on international surveys, including the Global Barometer Surveys.

Satisfaction with democracy can be thought of as one measure of popular contentment – with the current regime in power or the direction of the nation.1 For example, results of this survey and work by other researchers show that people who support the party or coalition in power (the “winners”) tend to be more satisfied than others.2

The question does not take into account institutional or other features that are sometimes used to characterize a democracy’s health. For example, our findings do not necessarily mirror ratings found in the Democracy Index, developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit, or Freedom House’s Freedom Ratings.

The satisfaction question also does not measure attitudes toward democratic values or belief in the principles of liberal democracy. That said, scholars have explored the link between views of how democracy is working and commitment to democratic principles. For example, one group of researchers found that across 54 countries, satisfaction with democracy was one of the key factors affecting people’s normative commitment to democracy.3 Our data, too, indicates that the more dissatisfied people are with democracy, the less likely they are to say representative democracy, rather than alternative models like technocracy, a strong leader model, or military rule, is a good way to govern their country (for more on this, see Chapter 1).

Some scholars also use the question about democracy’s performance to identify “dissatisfied democrats” – those committed to democratic institutions but dissatisfied with the current state of democracy in their country – a group some argue is important for preventing democracies from “back-sliding” into authoritarian regimes.4

1 Linde, Jonas, and Joakim Ekman. 2003. “

Satisfaction with democracy: A note on a frequently used indicator in comparative politics.” European Journal of Political Research.

2 Wells, Jason M., and Jonathan Krieckhaus. 2006. “

Does National Context Influence Democratic Satisfaction? A Multi-level Analysis.” Political Research Quarterly.

3 Chu, Yu-ham, Michael Bratton, Marta Lagos, Sandeep Shastri and Mark Tessler. 2008. “

Public Opinion and Democratic Legitimacy.” Journal of Democracy.

4 Norris, Pippa. Ed. 1999. “Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government.”

[/collapsible]

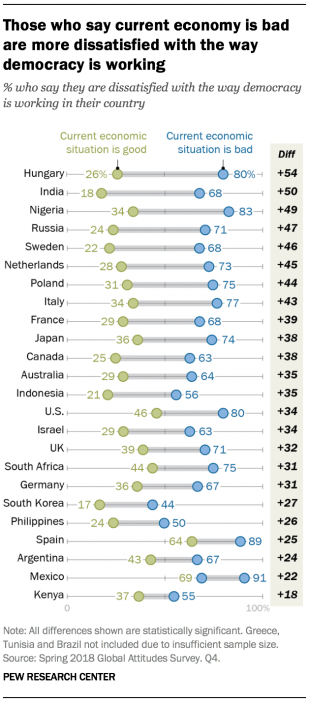

Economic discontent and democratic dissatisfaction

The link between views of the economy and assessments of democratic performance is strong. In 24 of 27 countries surveyed, people who say the national economy is in bad shape are more likely than those who say it is in good shape to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is working. In the other three countries surveyed, so few people say the economy is good that this relationship cannot be analyzed.

For example, eight-in-ten Hungarians who say the national economic situation is poor are also dissatisfied with the performance of the country’s democracy, compared with just 26% of those who believe the economic situation is good.

Views about economic opportunity also play a role. In 26 of 27 nations, those who believe their country is one in which most people cannot improve their standard of living are more likely to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is working.

However, personal income is not a major factor. And multilevel regression analysis suggests that, in general, demographic variables including gender, age and education are not strongly related to democratic dissatisfaction.

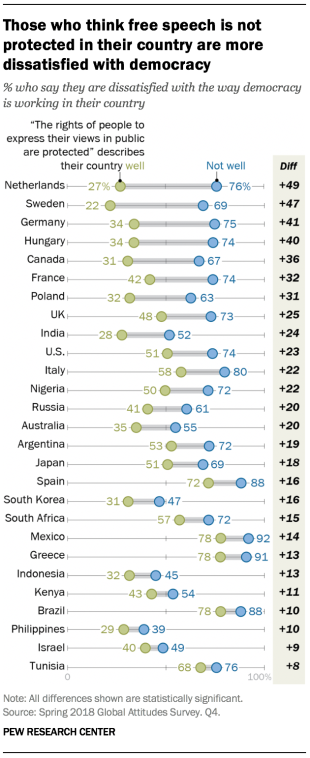

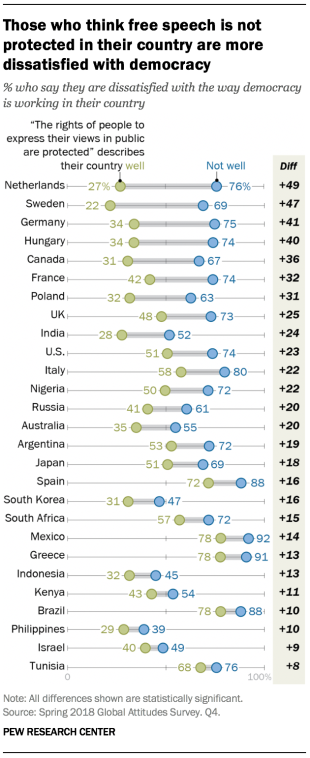

Individual rights and democratic performance

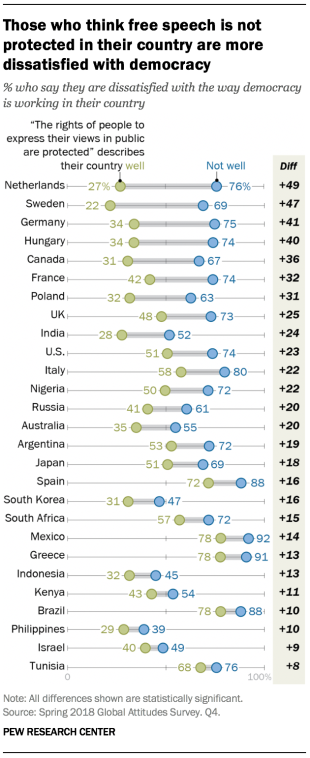

While views about economic conditions have a strong relationship with assessments of democratic performance, non-economic factors also play an important role. Opinions about how well democracy is working in a country are related to whether people believe their most fundamental rights are being respected.

In every nation studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is more common among people who say the statement “the rights of people to express their views in public are protected” does

not describe their country well. This pattern is especially apparent in Europe, where in nations such as the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany and Hungary those who believe free expression is not protected are significantly more likely to be unhappy with the state of democracy.

Discontent with the functioning of democracy is also linked to views about how people are treated within a country’s justice system. In 24 nations, dissatisfaction is particularly common among those who think the statement “the court system treats everyone fairly” does not describe their country well. Again, the pattern is especially intense in Europe. For example, among Hungarians who offer a negative assessment of the country’s courts, 68% are dissatisfied with the way democracy is working, while dissatisfaction is just 32% among those who believe the courts treat everyone fairly.

Frustration with politicians breeds dissatisfaction with democracycaption id="attachment_44106" align="alignnone" width="1024"]

Frustration with politicians breeds dissatisfaction with democracycaption id="attachment_44106" align="alignnone" width="1024"] A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

A woman shows her inked finger after voting in a village near Srinagar, India. (Saqib Majeed/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)[/caption]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union.

Bivariate and multilevel regression analyses (see Appendix A for methodological details) show that, among the factors studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is related to economic frustration, the status of individual rights, as well as perceptions that political elites are corrupt and do not care about average citizens. Additionally, in Europe the results suggest that dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is tied to views about the EU, opinions about whether immigrants are adopting national customs and attitudes toward populist parties.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 30,133 people in 27 countries from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

[collapsible]

Measuring satisfaction, dissatisfaction with how democracy is working

We measured satisfaction with the performance of democracy in each country using the following question: How satisfied are you with the way democracy is working in our country – very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not too satisfied, or not at all satisfied? This question is commonly used by academics and on international surveys, including the Global Barometer Surveys.

Satisfaction with democracy can be thought of as one measure of popular contentment – with the current regime in power or the direction of the nation.1 For example, results of this survey and work by other researchers show that people who support the party or coalition in power (the “winners”) tend to be more satisfied than others.2

The question does not take into account institutional or other features that are sometimes used to characterize a democracy’s health. For example, our findings do not necessarily mirror ratings found in the Democracy Index, developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit, or Freedom House’s Freedom Ratings.

The satisfaction question also does not measure attitudes toward democratic values or belief in the principles of liberal democracy. That said, scholars have explored the link between views of how democracy is working and commitment to democratic principles. For example, one group of researchers found that across 54 countries, satisfaction with democracy was one of the key factors affecting people’s normative commitment to democracy.3 Our data, too, indicates that the more dissatisfied people are with democracy, the less likely they are to say representative democracy, rather than alternative models like technocracy, a strong leader model, or military rule, is a good way to govern their country (for more on this, see Chapter 1).

Some scholars also use the question about democracy’s performance to identify “dissatisfied democrats” – those committed to democratic institutions but dissatisfied with the current state of democracy in their country – a group some argue is important for preventing democracies from “back-sliding” into authoritarian regimes.4

1 Linde, Jonas, and Joakim Ekman. 2003. “

Satisfaction with democracy: A note on a frequently used indicator in comparative politics.” European Journal of Political Research.

2 Wells, Jason M., and Jonathan Krieckhaus. 2006. “

Does National Context Influence Democratic Satisfaction? A Multi-level Analysis.” Political Research Quarterly.

3 Chu, Yu-ham, Michael Bratton, Marta Lagos, Sandeep Shastri and Mark Tessler. 2008. “

Public Opinion and Democratic Legitimacy.” Journal of Democracy.

4 Norris, Pippa. Ed. 1999. “Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government.”

[/collapsible]

Economic discontent and democratic dissatisfaction

The link between views of the economy and assessments of democratic performance is strong. In 24 of 27 countries surveyed, people who say the national economy is in bad shape are more likely than those who say it is in good shape to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is working. In the other three countries surveyed, so few people say the economy is good that this relationship cannot be analyzed.

For example, eight-in-ten Hungarians who say the national economic situation is poor are also dissatisfied with the performance of the country’s democracy, compared with just 26% of those who believe the economic situation is good.

Views about economic opportunity also play a role. In 26 of 27 nations, those who believe their country is one in which most people cannot improve their standard of living are more likely to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is working.

However, personal income is not a major factor. And multilevel regression analysis suggests that, in general, demographic variables including gender, age and education are not strongly related to democratic dissatisfaction.

Individual rights and democratic performance

While views about economic conditions have a strong relationship with assessments of democratic performance, non-economic factors also play an important role. Opinions about how well democracy is working in a country are related to whether people believe their most fundamental rights are being respected.

In every nation studied, dissatisfaction with democracy is more common among people who say the statement “the rights of people to express their views in public are protected” does

not describe their country well. This pattern is especially apparent in Europe, where in nations such as the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany and Hungary those who believe free expression is not protected are significantly more likely to be unhappy with the state of democracy.

Discontent with the functioning of democracy is also linked to views about how people are treated within a country’s justice system. In 24 nations, dissatisfaction is particularly common among those who think the statement “the court system treats everyone fairly” does not describe their country well. Again, the pattern is especially intense in Europe. For example, among Hungarians who offer a negative assessment of the country’s courts, 68% are dissatisfied with the way democracy is working, while dissatisfaction is just 32% among those who believe the courts treat everyone fairly.

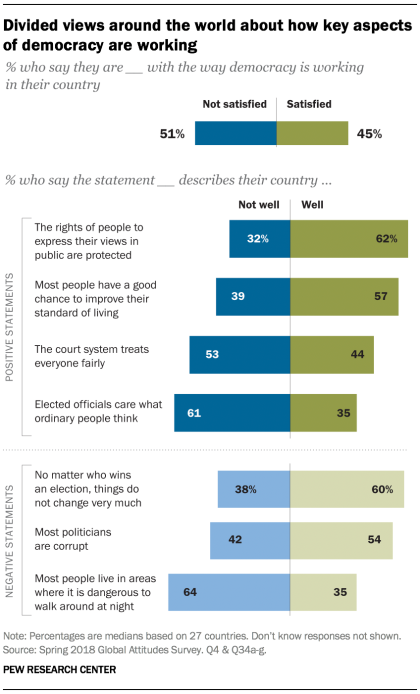

Frustration with politicians breeds dissatisfaction with democracy

Frustration with politicians breeds dissatisfaction with democracy

In addition to views about political rights, attitudes toward politicians also influence the degree to which people are satisfied or dissatisfied with the performance of their country’s democracy. For instance, dissatisfaction is pervasive among people who see politicians as uncaring and out of touch.

In 26 nations, unhappiness with the current functioning of democracy is more common among those who believe the statement “elected officials care what ordinary people think” does not describe their country well.

Many also say the politicians in their country are corrupt, and those who hold this view are consistently more dissatisfied with how their democracy is functioning.

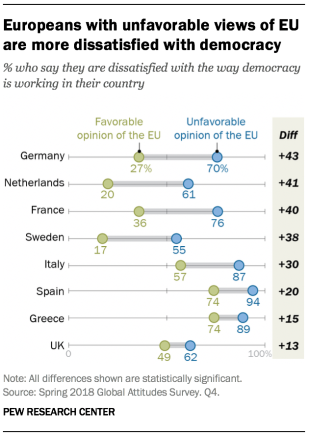

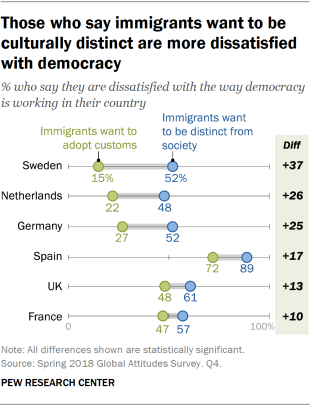

Concerns about immigrants, dislike of EU and favorable opinion of populist parties are tied to dissatisfaction in Europe

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy.

Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Dem have documented global declines in the health of democracy. The link between views of the economy and assessments of democratic performance is strong. In 24 of 27 countries surveyed, people who say the national economy is in bad shape are more likely than those who say it is in good shape to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is working. In the other three countries surveyed, so few people say the economy is good that this relationship cannot be analyzed.

The link between views of the economy and assessments of democratic performance is strong. In 24 of 27 countries surveyed, people who say the national economy is in bad shape are more likely than those who say it is in good shape to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is working. In the other three countries surveyed, so few people say the economy is good that this relationship cannot be analyzed. While views about economic conditions have a strong relationship with assessments of democratic performance, non-economic factors also play an important role. Opinions about how well democracy is working in a country are related to whether people believe their most fundamental rights are being respected.

While views about economic conditions have a strong relationship with assessments of democratic performance, non-economic factors also play an important role. Opinions about how well democracy is working in a country are related to whether people believe their most fundamental rights are being respected. Frustration with politicians breeds dissatisfaction with democracy

Frustration with politicians breeds dissatisfaction with democracy The study highlights additional factors related to democratic dissatisfaction in Europe, including attitudes toward the EU. As a recent Pew Research Center report highlighted, Europeans still tend to associate the EU with noble aspirations, such as peace, prosperity and democracy. At the same time, they also say the Brussels-based institution is inefficient, intrusive and out of touch with ordinary citizens.

The study highlights additional factors related to democratic dissatisfaction in Europe, including attitudes toward the EU. As a recent Pew Research Center report highlighted, Europeans still tend to associate the EU with noble aspirations, such as peace, prosperity and democracy. At the same time, they also say the Brussels-based institution is inefficient, intrusive and out of touch with ordinary citizens. Immigration has been a particularly contentious issue in Europe since 2015, when refugees from the Middle East and elsewhere entered Europe in record numbers. Across the region, concerns about how immigrants fit into society are linked to democratic dissatisfaction.

Immigration has been a particularly contentious issue in Europe since 2015, when refugees from the Middle East and elsewhere entered Europe in record numbers. Across the region, concerns about how immigrants fit into society are linked to democratic dissatisfaction.