Organizations that track gender equality across a variety of outcomes related to health, economics, politics and education – such as the United Nations Development Program and the World Economic Forum – find widespread inequality. For example, women account for less than half of the labor force globally, and few nations have ever had a female leader.

Organizations that track gender equality across a variety of outcomes related to health, economics, politics and education – such as the United Nations Development Program and the World Economic Forum – find widespread inequality. For example, women account for less than half of the labor force globally, and few nations have ever had a female leader.

In their most recent Global Gender Gap report, the World Economic Forum projects that it will take more than a century to close the current gender gap in the countries it covers. Yet, overall trends show increasing gender equality in many countries.

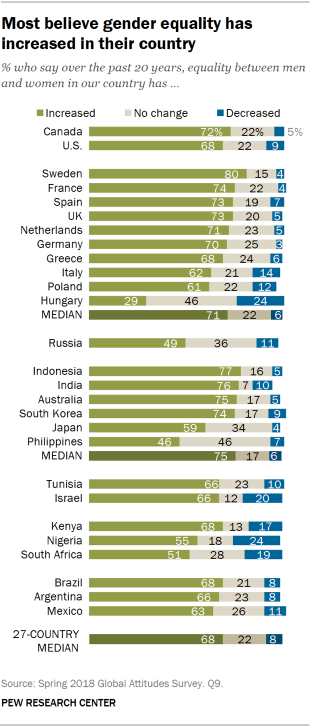

People around the world seem cognizant of these changes in their own country. Majorities in 23 of the 27 countries surveyed believe that equality between men and women in their country has increased in the past two decades.

The countries with the highest and lowest shares saying gender equality has increased can both be found in Europe. In Sweden – one of the most egalitarian countries in Europe, according to the European Institute for Gender Equality – 80% say equality has increased in the past two decades. Hungarians, however, have seen much less positive change in their country, which is one of the European Union’s least egalitarian nations, according to the same source. Fewer than a third of Hungarians (29%) believe gender equality has increased in their society.

Many in the Asia-Pacific region view their countries as becoming more egalitarian, including roughly three-quarters of Indonesians (77%), Indians (76%), Australians (75%) and South Koreans (74%). A majority of Japanese also hold this view, though 34% say there has been no change in the past two decades. Filipinos are divided, however. Fewer than half (46%) believe men and women have become more equal in their country, while the same share believes there has been no change.

In some countries, perceptions of gender equality vary by gender. In many of the countries surveyed, men are more likely than women to say that their countries have become more egalitarian. Women, on the other hand, are more likely to say there has been no change in most of these countries.

Widespread positive attitudes toward increasing gender equality

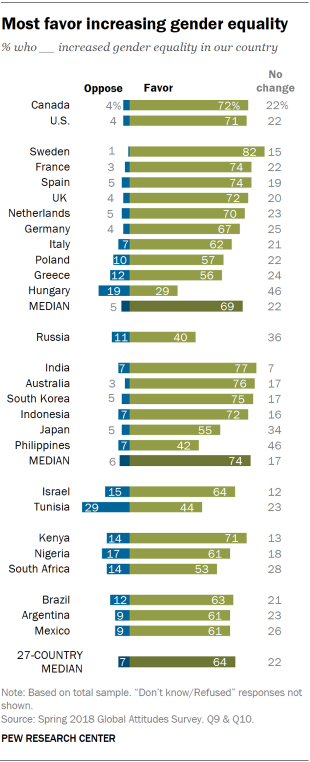

Many are in favor of the move toward greater gender equality that publics believe is happening in their countries. Respondents were classified as favoring increasing equality if they either believed gender equality was increasing and viewed this as a good thing for the country, or felt gender equality was decreasing and saw this as bad.

Many are in favor of the move toward greater gender equality that publics believe is happening in their countries. Respondents were classified as favoring increasing equality if they either believed gender equality was increasing and viewed this as a good thing for the country, or felt gender equality was decreasing and saw this as bad.

Again, Sweden and Hungary stand out among the nations surveyed. A large majority of Swedes (82%) favor increasing gender equality in their country. By comparison, only 29% of Hungarians agree. This share is relatively low in part because of the large number of Hungarians who say there has been no change in their country (46%), which does not allow us to categorize their view of changing gender equality. Yet, almost two-in-ten oppose increasing gender equality in their society, one of the highest shares among the countries surveyed.

Tunisians are the most likely among those surveyed to oppose growing gender equality in their country. Just under a third either say increasing gender equality is a bad thing or that decreasing gender equality is a good thing.

Tunisians are the most likely among those surveyed to oppose growing gender equality in their country. Just under a third either say increasing gender equality is a bad thing or that decreasing gender equality is a good thing.

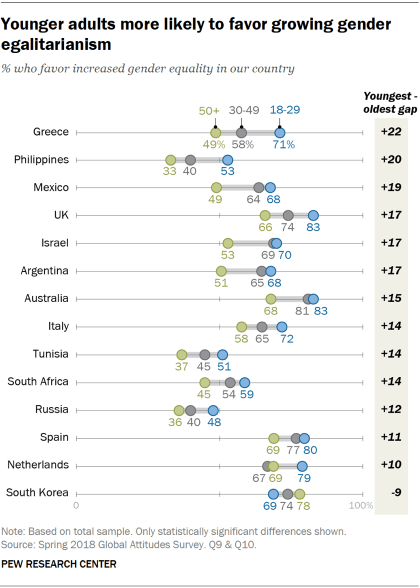

In about half of the countries surveyed, younger adults are more likely to favor increasing gender equality than adults ages 50 and older.

In Greece, 71% of people ages 18 to 29 approve of greater equality in their society, compared with 49% of people 50 and older. A similarly large age difference is found in the Philippines, where 53% of young adults but only 33% of older adults favor more equality between men and women.

In South Korea, this pattern is reversed; older adults are more likely than younger adults to approve of increased equality.

Attitudes toward increasing gender parity also differ by educational attainment. In 21 countries, people with more education are more likely than those with less education to favor growing equality.

Attitudes toward increasing gender parity also differ by educational attainment. In 21 countries, people with more education are more likely than those with less education to favor growing equality.

This difference is especially pronounced in Argentina and Mexico. For example, 81% of Argentines with a postsecondary education favor greater gender equality, compared with 58% of Argentines with a secondary education or below.

Differences by education can also be found in the U.S., Canada, and all European countries surveyed.

There are few ideological differences in support for greater gender equality, but in Sweden and France – two countries with strong support overall – some partisan differences emerge. People who hold a favorable view of France’s National Rally are less likely to favor increasing gender parity (64%) than those with an unfavorable view of the party (76%). Similarly, people with a favorable opinion of the far-right Sweden Democrats (76%) are less likely than people with an unfavorable opinion (85%) to approve of gender equality, though support is generally high among both groups.