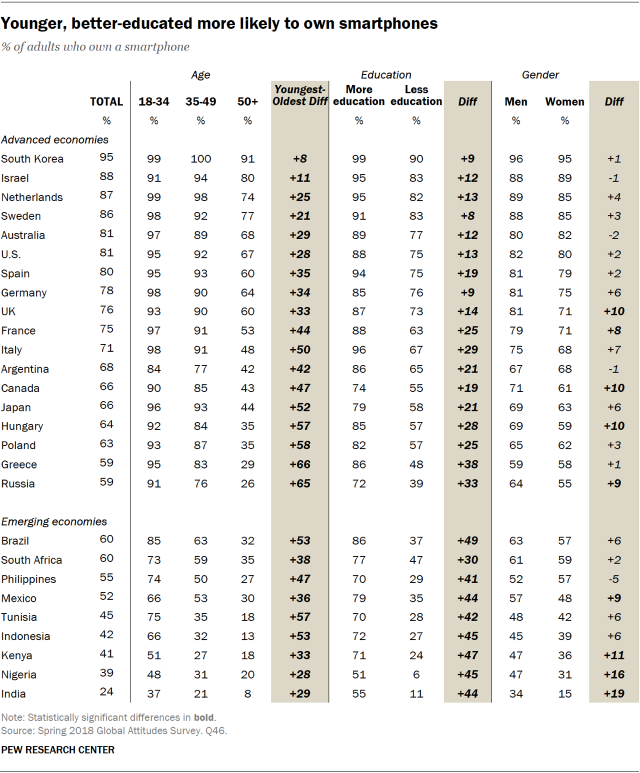

As smartphone ownership has increased in both advanced and emerging economies, the growth has often been uneven. Age, gender, education levels and income all contribute to who owns a smartphone – though, often, age is the key factor associated with ownership.

In advanced and emerging economies alike, younger people are much more digitally connected than older generations. In every country surveyed, those under 35 are more likely to own smartphones, to use the internet and to use social media than those ages 50 and older. For example, nearly all Japanese under 35 own a smartphone (96%), while fewer than half of those over 50 do (44%), a gap of 52 percentage points. The gap is 53 points in Brazil, where 85% of those ages 18 to 34 own a smartphone compared with just 32% of those 50 and older. Even in countries like Germany and Australia, where smartphone ownership rates far outpace those in Brazil, younger adults are far more likely to own smartphones than older age groups.

Younger age groups are also much more likely to use social media sites like Facebook than older ones. In Argentina, nine-in-ten adults under 35 use social media, compared with roughly four-in-ten of those ages 50 and older (38%). And in every emerging economy surveyed but India, more than half of those ages 18 to 34 use social media, while no more than about a third of those 50 and older do in all emerging economies. In South Africa for example, 70% of 18- to 34-year-olds use social media, compared with just 19% of those 50 and older.

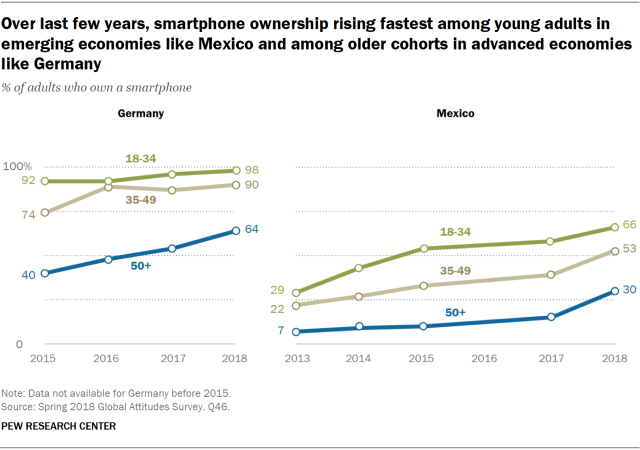

But even as these age gaps in smartphone ownership, internet use and social media use persist in most countries, they appear to be closing somewhat in advanced economies. Take smartphone ownership as an example. In advanced economies including the UK, U.S. and France, smartphone ownership has been widespread among the younger age group for some time. But the age gap in smartphone ownership has been closing in recent years as smartphone adoption among the older group has grown. (See Appendix E for detailed tables).

The opposite pattern is visible in emerging economies: In many of these countries, the age gap in ownership is growing. Over the past five years, smartphone adoption has soared among young adults in emerging economies. Across nine emerging economies surveyed in 2013, around one-in-four adults ages 18 to 34 owned smartphones. By 2018, that share had grown to at least around two-thirds in most countries. Those ages 50 and older, however, have been much slower to become smartphone owners. Generally, fewer than one-in-ten owned smartphones in 2013, and while that share has grown substantially in all countries, it stands at around one-in-five today.

The opposite pattern is visible in emerging economies: In many of these countries, the age gap in ownership is growing. Over the past five years, smartphone adoption has soared among young adults in emerging economies. Across nine emerging economies surveyed in 2013, around one-in-four adults ages 18 to 34 owned smartphones. By 2018, that share had grown to at least around two-thirds in most countries. Those ages 50 and older, however, have been much slower to become smartphone owners. Generally, fewer than one-in-ten owned smartphones in 2013, and while that share has grown substantially in all countries, it stands at around one-in-five today.

Germany and Mexico are examples of these divergent patterns. In 2015, 92% of Germans under 35 owned a smartphone, compared with just 40% of those ages 50 and above. Three years later, smartphone ownership had ticked up to 98% among younger Germans and grown to nearly two-thirds (64%) of the 50-plus population. Data on smartphone ownership in Mexico stretches back to 2013, when 29% of 18- to 34-year-olds owned smartphones compared with just 7% of Mexicans ages 50 and older. By 2018, smartphone ownership jumped to roughly two-thirds of young Mexicans but remains at just three-in-ten among those ages 50 and above.

In most countries, men and women are equally likely to own smartphones

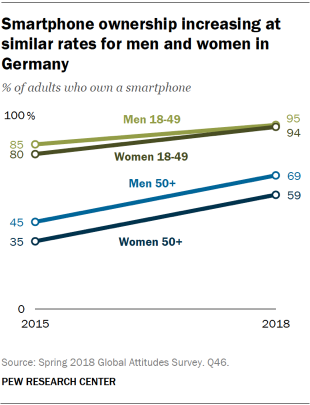

Whereas age is one of the key factors associated with smartphone ownership, internet use and social media use across all the countries surveyed, there are fewer differences when it comes to men and women and their technology adoption. In 18 of the 27 countries, for example, men and women are about equally likely to own smartphones. And the nine countries where men are more likely to own smartphones than women – Canada, France, Hungary, the UK, Russia, India, Kenya, Nigeria and Mexico – do not fit a single pattern in terms of economic development. Moreover, in most of these countries, the gap in ownership is relatively small.

In most countries, too, there are relatively minimal gender gaps in social media use. In some advanced economies, like the U.S., Spain and Australia, women are more likely than men to use social media sites like Facebook, while in other advanced economies, such as Japan and France, men are slightly more likely to use these sites. Only in Kenya, Nigeria and India – three countries where smartphone ownership also differs substantially by gender – are there relatively large gender differences in social media use. In these three countries, women are less likely than men to use social media sites. While about half of Kenyan men use social media, for example, only a third of women do. (See Appendix E for detailed tables).

Not only are gender gaps in smartphone ownership, internet use and social media use relatively small in most countries studied, but smartphone ownership has increased by similar degrees for both men and women. For example, in Indonesia today, 45% of men own a smartphone, compared with 39% of women. This gap of 6 percentage points is nearly identical to the 4-point gap seen in 2013, when 13% of men and 9% of women owned smartphones. Similarly, in Australia, nearly identical percentages of men and women own smartphones today (80% and 82%, respectively) – and this has been the case since the question was first asked in 2015, when 78% of men and 77% of women reported owning smartphones.

In most countries, differences between men and women in the same age range tend to be smaller than differences between age groups of the same gender. Younger people – whether men or women – tend to be much more likely to own smartphones than their elders. Once again, Germany provides a relatively clear example of the broader pattern: German men and women under 50 were similarly likely to own smartphones in 2015, and today they own smartphones at virtually equal rates (95% and 94%, respectively). And, while German men ages 50 and older are about as likely to own smartphones as German women ages 50 and older (69% vs. 59%), this gap is smaller than the gap between younger and older Germans.

Both age and gender are important factors in smartphone ownership in India. Specifically, Indian men ages 18 to 49 are more likely than people of any other group to own a smartphone, and they have become smartphone owners at a faster rate as well. Five years ago, one-in-five Indian men in this age group owned a smartphone, and today, 42% do – an increase of 22 percentage points. More Indian women ages 18 to 49 have become smartphone owners as well, but they are just 12 points more likely to own smartphones today than they were in 2013. And Indian women ages 50 and older have made no gains in smartphone ownership over past five years: About one-in-twenty owned a smartphone at each point in time.

Both age and gender are important factors in smartphone ownership in India. Specifically, Indian men ages 18 to 49 are more likely than people of any other group to own a smartphone, and they have become smartphone owners at a faster rate as well. Five years ago, one-in-five Indian men in this age group owned a smartphone, and today, 42% do – an increase of 22 percentage points. More Indian women ages 18 to 49 have become smartphone owners as well, but they are just 12 points more likely to own smartphones today than they were in 2013. And Indian women ages 50 and older have made no gains in smartphone ownership over past five years: About one-in-twenty owned a smartphone at each point in time.

More educated, higher-income people are more likely to be digitally connected

Income and education are related to smartphone ownership, internet use and social media use (see Appendix E for detailed tables). In every country surveyed, for example, better-educated and higher-income people are more likely to go online than those with less education or lower incomes.

Income and education are related to smartphone ownership, internet use and social media use (see Appendix E for detailed tables). In every country surveyed, for example, better-educated and higher-income people are more likely to go online than those with less education or lower incomes.

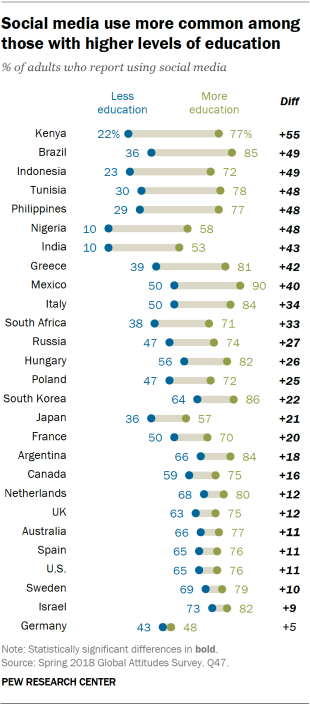

When it comes to social media use, the education gaps in emerging economies are wide. Indonesia illustrates the general pattern. There, nearly three-in-four adults (72%) with a secondary education or more report using social media sites like Facebook compared with about a quarter of adults with lower levels of education (23%), a gap of 49 percentage points.

In advanced economies too, people with higher levels of education are more likely to use social media than those with lower levels of education. In these countries, generally around three-quarters of those with higher levels of education use social media, while fewer than two-thirds of those with lower levels of education do. In the UK, for instance, 75% of those with more than a secondary education use social media, compared with 63% of those with a secondary education or less.

Income gaps in social media use tend to be somewhat narrower than education gaps, but in nearly every country surveyed, people with higher incomes are more likely to use social media than people with lower incomes.