As the pace and magnitude of cyberattacks have increased around the world, a new survey shows that people in multiple countries think it is likely that government data, public infrastructure and elections will be targeted by future hacks. Opinion is mixed, however, on whether their nations are prepared for such events.

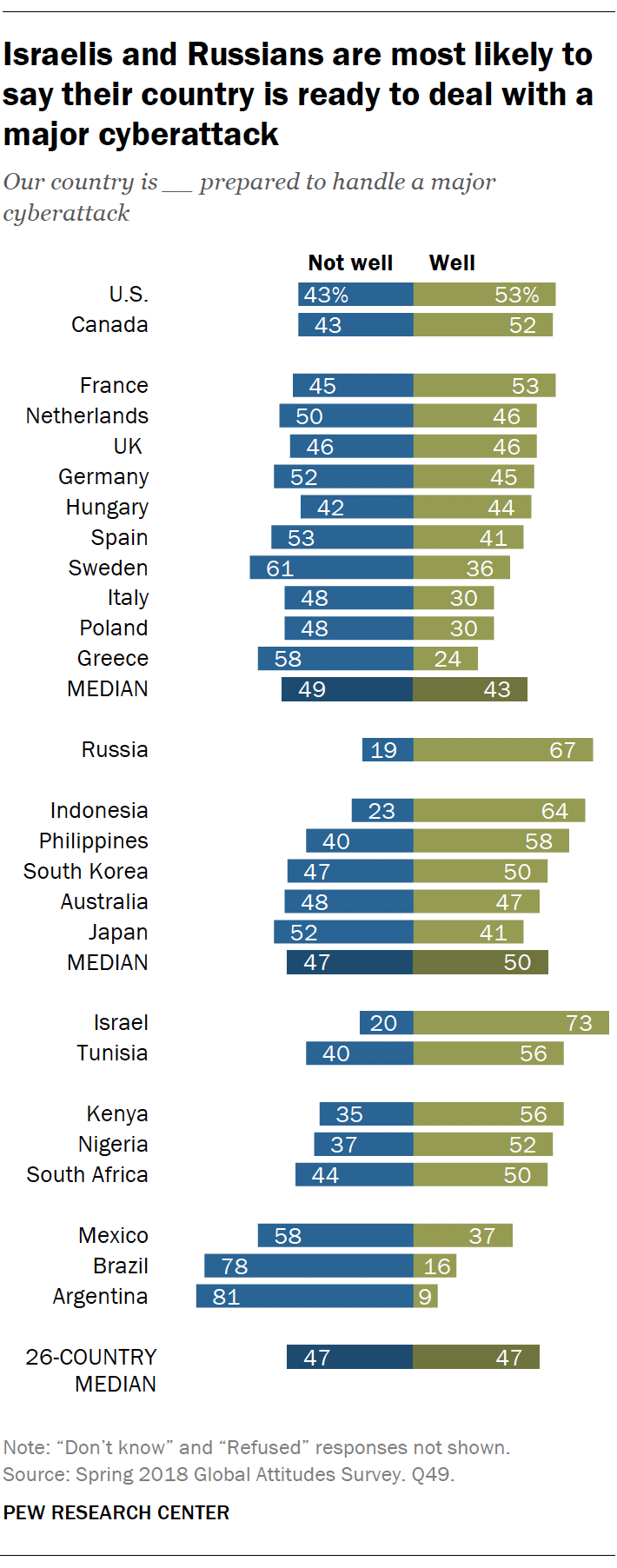

Across the 26 countries surveyed by Pew Research Center, nearly half (47%) say their country is well prepared to handle a major cyberattack, but an equal share disagrees. Attitudes vary widely by country. Two-thirds or more in Israel (73%) and Russia (67%), for example, say their nations are ready for a major cyber incident, while fewer than one-in-five Brazilians (16%) and Argentines (9%) say the same. In the United States, just over half of Americans (53%) think their country is prepared to handle a major cyberattack.

But half or more in some of the world’s largest economies, including Germany and Japan, think they are not ready for cyberattacks.

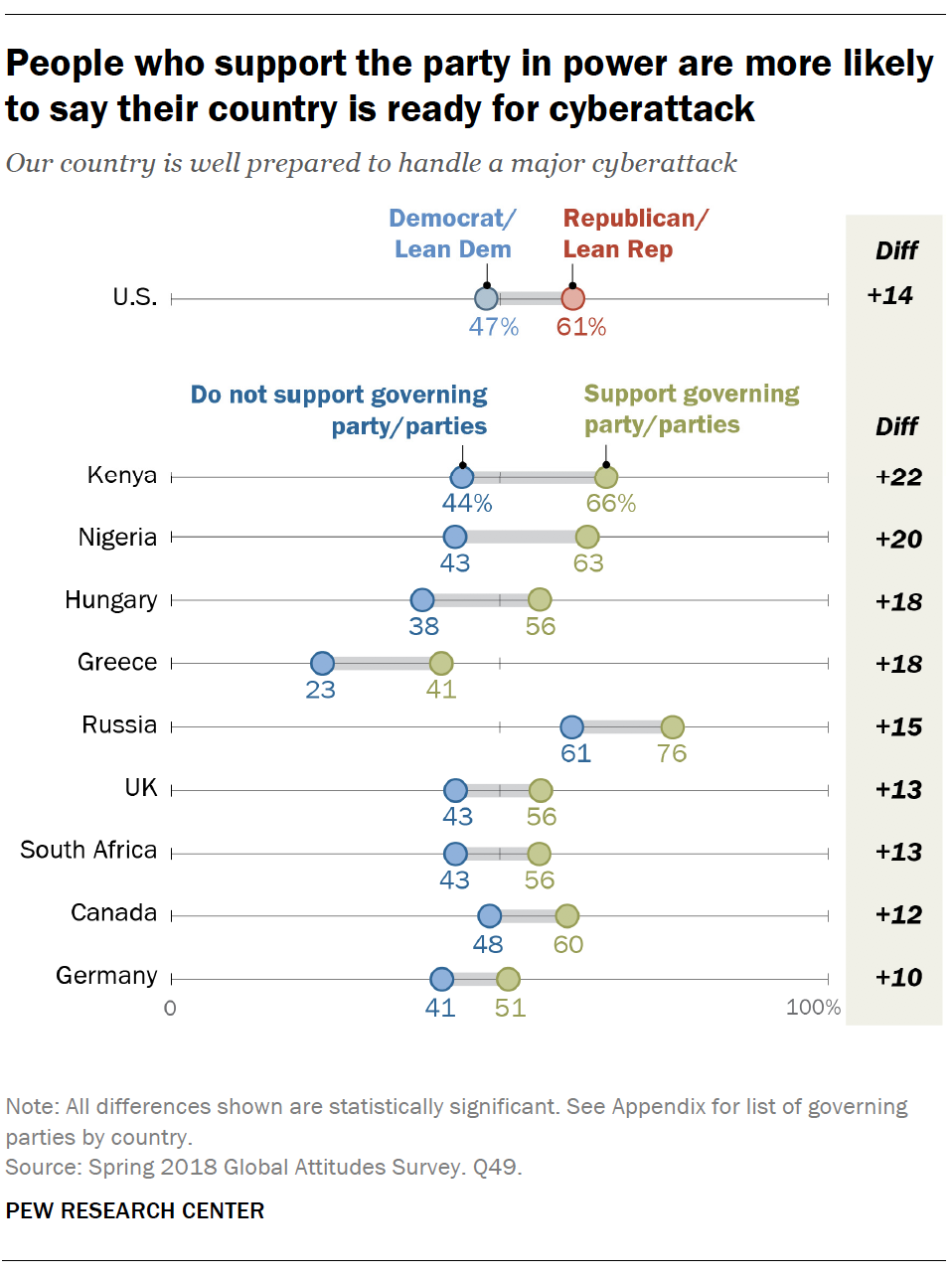

In many cases, views about a country’s preparedness are shaped in part by partisanship and attitudes toward the party in power. People who support the governing party are often more likely to think their nation can handle a large cyber hack. In the U.S., Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are far more likely (61%) than Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (47%) to say the country is prepared for an attack on computer systems.

In many cases, views about a country’s preparedness are shaped in part by partisanship and attitudes toward the party in power. People who support the governing party are often more likely to think their nation can handle a large cyber hack. In the U.S., Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are far more likely (61%) than Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (47%) to say the country is prepared for an attack on computer systems.

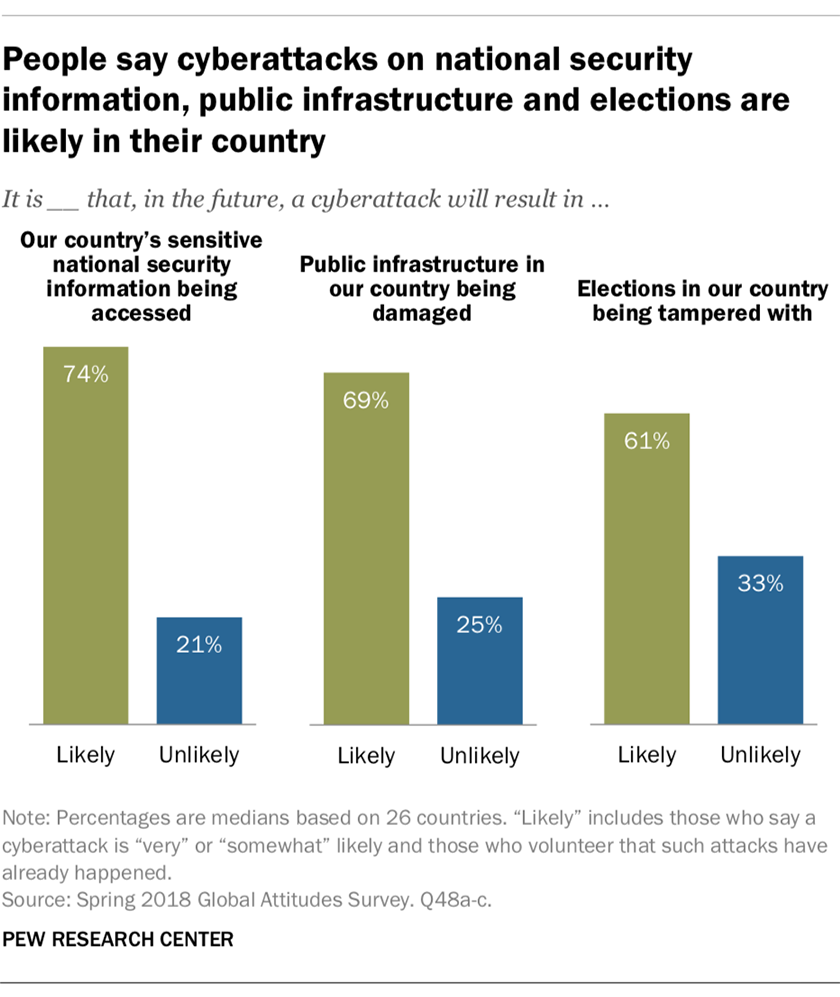

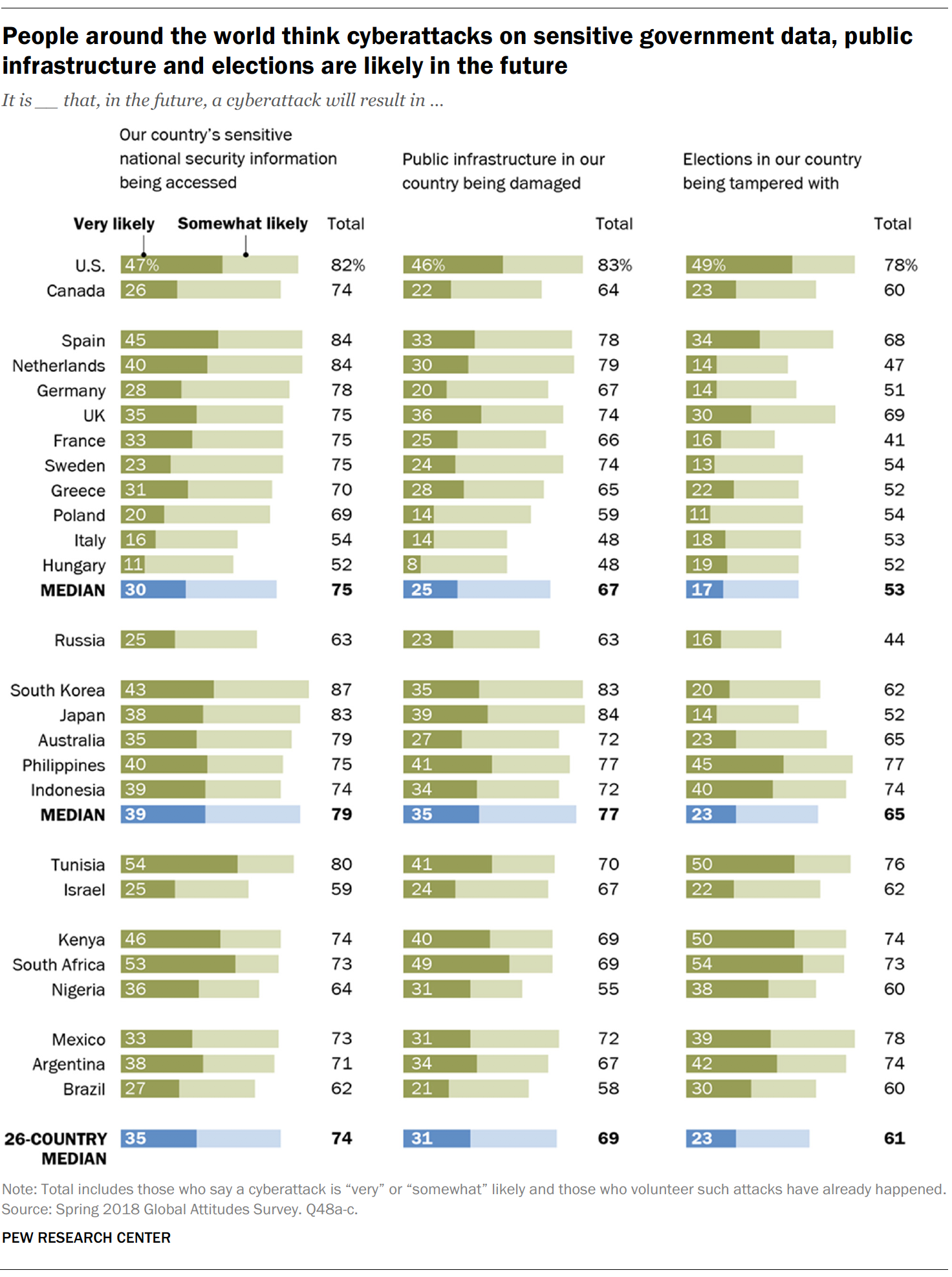

When it comes to the likelihood of cyberattacks, most say that an attack where sensitive national security information will be accessed is either very or somewhat likely (or volunteer that this has already happened). A median of 74% across the 26 countries hold this view.

While relative fears about the likelihood of attacks on public infrastructure and election tampering are less widespread than concerns about national security data being breached, a median of 69% and 61%, respectively, say these are likely to happen. Worries about infrastructure attacks are more prevalent among older respondents in a handful of nations, such as in Sweden, Canada and Germany. Meanwhile, relatively few Russians say election tampering is likely to happen to their nation (44%).

Of the 26 publics surveyed, Americans are among the most likely to say cyberattacks will happen. Roughly eight-in-ten or more in the U.S. say public infrastructure will be damaged (83%), national security information will be accessed (82%), or elections will be tampered with (78%) via cyberattack. Democrats in the U.S. are much more convinced of likely election tampering (87%) than are Republicans (66%), and older Americans are more worried about infrastructure damage.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey in 26 countries among 27,612 respondents from May 14 to Aug. 12, 2018.

Globally, publics are split on whether their country is prepared for a major cyberattack

Several of the nations surveyed have been victims of notable cyberattacks against their public infrastructure or government agencies in recent years. Overall, publics are split on whether their country is prepared for such attacks: A median of 47% say it is, while the same proportion says it is not.

Several of the nations surveyed have been victims of notable cyberattacks against their public infrastructure or government agencies in recent years. Overall, publics are split on whether their country is prepared for such attacks: A median of 47% say it is, while the same proportion says it is not.

In the U.S., which has been the victim of over 100 major cyber incidents since 2006, more say the country is prepared than unprepared for a major cyberattack (53% vs. 43%).

Europeans, on balance, are more pessimistic than optimistic about whether their countries can deal with a large-scale cyber hack. France is the only country in the region where more than half say it is well-prepared to deal with a cyber incident.

Public doubts about the ability to fend off a major cyber hack are especially widespread in some Latin American countries. Roughly eight-in-ten in both Argentina and Brazil say their countries are not prepared, including 49% of Argentines and 42% of Brazilians who describe their countries as not prepared at all.

Not all publics feel ill-prepared for an attack. Two-thirds of Russians and 64% of Indonesians believe their country is ready to address a significant attack. Israelis are even more optimistic: Almost three-quarters agree that their nation is prepared for a major cyberattack. Meanwhile, in three sub-Saharan African nations surveyed, half or more say they are well prepared for such attacks.

In some Asian-Pacific nations surveyed, there are doubts about the ability to protect against cyberstrikes. Roughly half in Japan (52%), Australia (48%) and South Korea (47%) say their country is not well prepared to handle a major cyberattack.

In 10 of the nations surveyed, perceptions of readiness are higher among supporters of the party or parties in power. In the U.S., for example, 61% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents believe the U.S. is well-prepared to deal with a major cyber incident. Fewer than half of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (47%) agree.

In 10 of the nations surveyed, perceptions of readiness are higher among supporters of the party or parties in power. In the U.S., for example, 61% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents believe the U.S. is well-prepared to deal with a major cyber incident. Fewer than half of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (47%) agree.

Roughly three-quarters of Russians who support President Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party are optimistic that their country could handle an attack, compared with 61% among those who do not support the party. A similar pattern is found in a diverse set of countries across Africa and Europe, as well as in Canada.

National security breaches seen as most likely form of cyberattack, but worries about infrastructure damage and election tampering abound

There is general agreement across the 26 countries surveyed that all three forms of cyberattacks asked about – national security information being accessed, public infrastructure being damaged, and elections being tampered with – are likely scenarios.

Concerns about sensitive government information being hacked are especially widespread. Half or more in each country surveyed say a cyberattack that accesses confidential government data is likely to occur. This includes eight-in-ten or more in South Korea, Spain, the Netherlands, Japan, the U.S. and Tunisia. Almost half of Americans (47%) say the accessing of sensitive national security data is very likely to happen or has already occurred.

Across the 10 European countries polled, a median of three-quarters say national security hacking is likely, although concern is less acute in Italy (54%) and Hungary (52%). Meanwhile, nearly eight-in-ten across five Asian-Pacific nations surveyed say national security data being accessed by hackers is likely.

Worries about damage to public infrastructure are not as common as worries about vulnerabilities in national security data, but roughly half or more in every country surveyed believe it is likely. Concern is highest in Japan (84%), the U.S. and South Korea (83% each). But two-thirds across Europe and majorities in the Middle Eastern, sub-Saharan African and Latin American countries surveyed also deem infrastructure attacks likely.

Election tampering is seen as likely by a median of 61% across the 26 countries surveyed. Nearly eight-in-ten Americans as well as Mexicans (78% each) say that elections are likely to be tampered with. Roughly three-quarters in the Philippines, Tunisia, Kenya, Argentina, Indonesia and South Africa share this view. The French, Russians and Dutch are the least concerned about election tampering: Fewer than half in each country say cyberattacks against elections are likely.

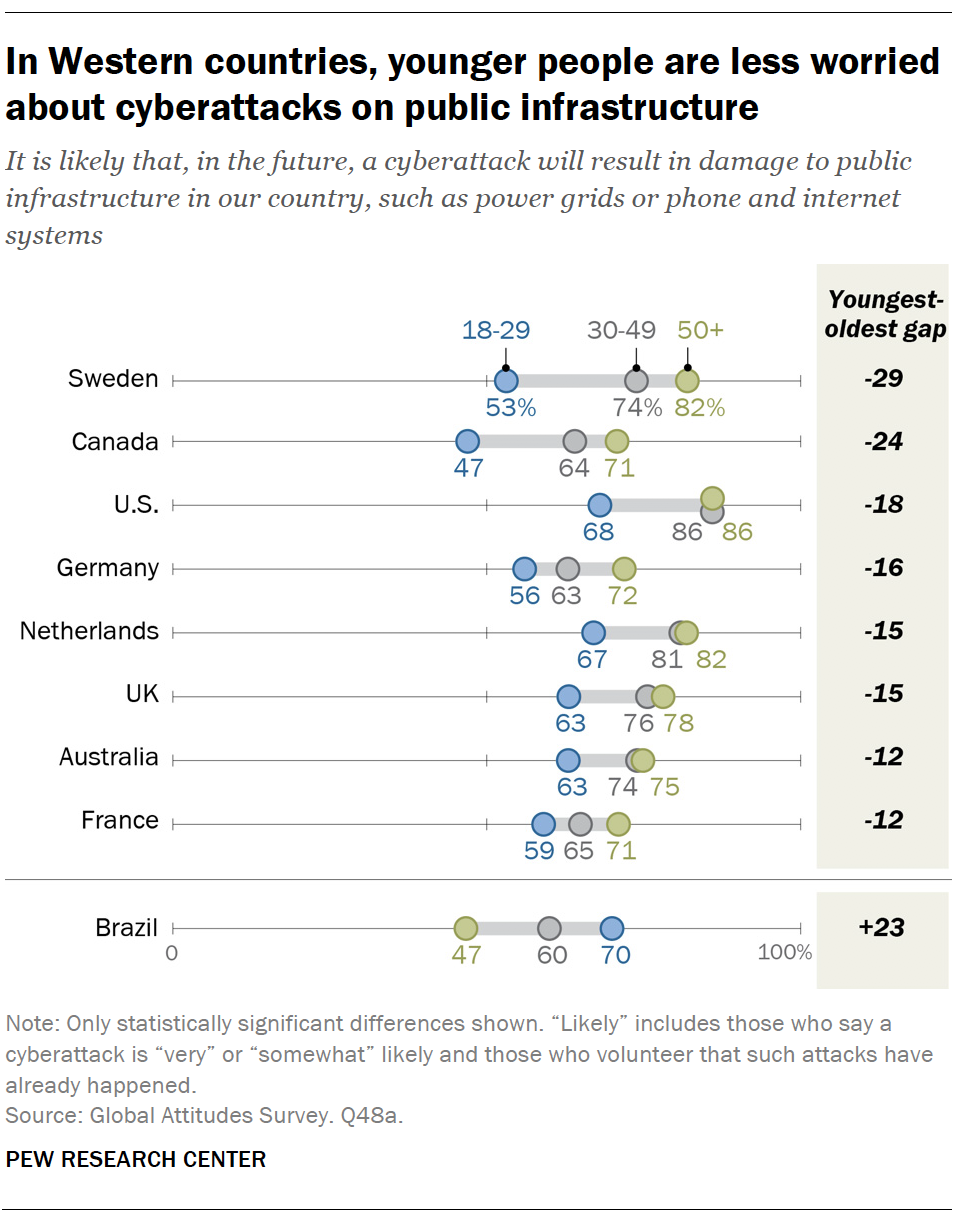

In many Western countries, younger people are less concerned than those 50 and older about potential attacks on public infrastructure, such as power grids and internet systems. This difference is largest in Sweden, where only 53% of those ages 18 to 29 think an attack on infrastructure is likely, compared with 82% of Swedes ages 50 and up. Large double-digit gaps also occur in Canada, the U.S., Australia and most of the Western European countries polled.

In many Western countries, younger people are less concerned than those 50 and older about potential attacks on public infrastructure, such as power grids and internet systems. This difference is largest in Sweden, where only 53% of those ages 18 to 29 think an attack on infrastructure is likely, compared with 82% of Swedes ages 50 and up. Large double-digit gaps also occur in Canada, the U.S., Australia and most of the Western European countries polled.

The pattern on this question is reversed in Brazil, where younger people are more worried than those 50 and older about cyberattacks against public infrastructure.

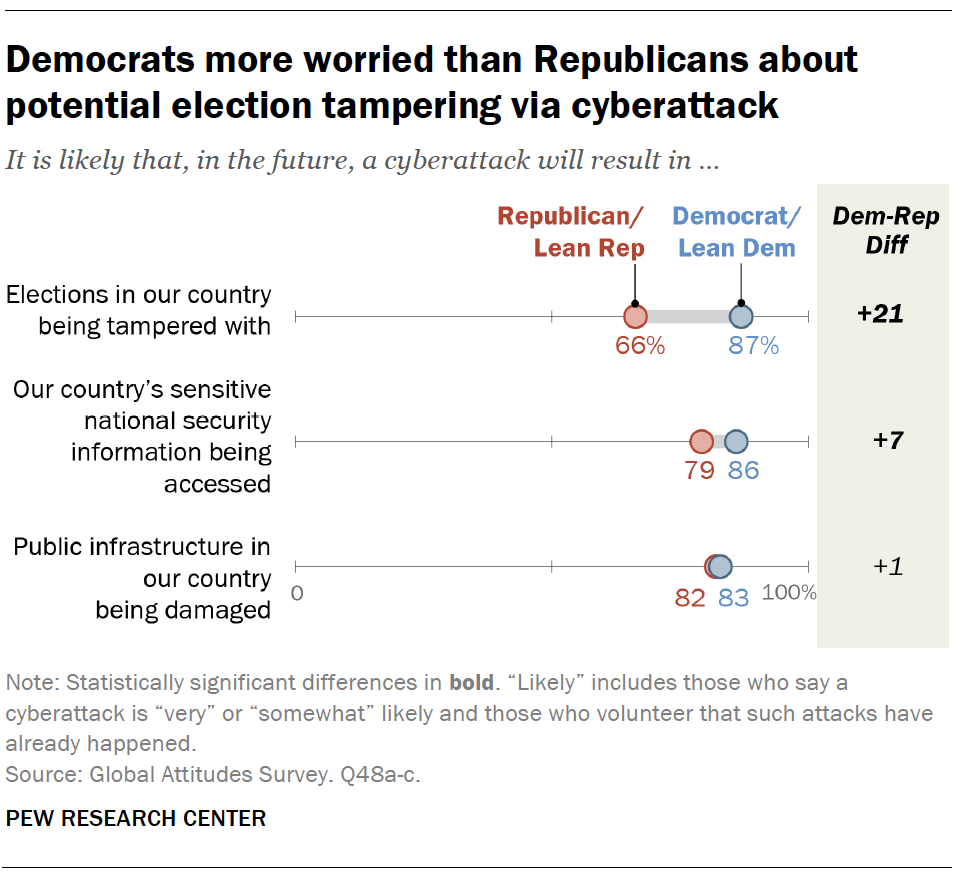

In the U.S., there is a noticeable partisan gap on the likelihood of an election cyberattack. Nearly nine-in-ten Democrats (87%) say it is likely, compared with 66% of Republicans. Democrats are also slightly more likely to worry about hackers obtaining sensitive national security information. But there is no significant difference in views of the likelihood of attacks on public infrastructure.

In the U.S., there is a noticeable partisan gap on the likelihood of an election cyberattack. Nearly nine-in-ten Democrats (87%) say it is likely, compared with 66% of Republicans. Democrats are also slightly more likely to worry about hackers obtaining sensitive national security information. But there is no significant difference in views of the likelihood of attacks on public infrastructure.