Americans divided on trade

Since at least 2002, more than half of Americans have embraced the idea that growing trade and business ties between the United States and other nations is a good thing. Today, more than seven-in-ten Americans (74%) hold this view, up from 68% in 2014.

Since at least 2002, more than half of Americans have embraced the idea that growing trade and business ties between the United States and other nations is a good thing. Today, more than seven-in-ten Americans (74%) hold this view, up from 68% in 2014.

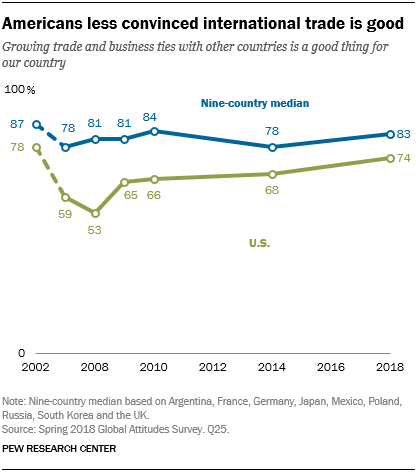

Even though most Americans are open to trade as a matter of principle, their enthusiasm has long trailed that in some other countries. Trends in the U.S. and nine other countries surveyed regularly since 2002 reveal a consistent gap between American and international levels of support for trade. Notably, U.S. support for increased trade declined substantially in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, then rebounded sharply in 2009 and has improved since then.

Since at least 2002, more than half of Americans have embraced the idea that growing trade and business ties between the United States and other nations is a good thing. Today, more than seven-in-ten Americans (74%) hold this view, up from 68% in 2014.

Asked specifically about granting access to the U.S. market through negotiated trade deals, Americans support such action less than they do trade in general. In 2018, 56% of Americans say free trade agreements between the U.S. and other countries have generally been a good thing for the nation, 18 percentage points lower than support for growing trade and business ties. This has been a consistent pattern since this question was first asked in 2009.

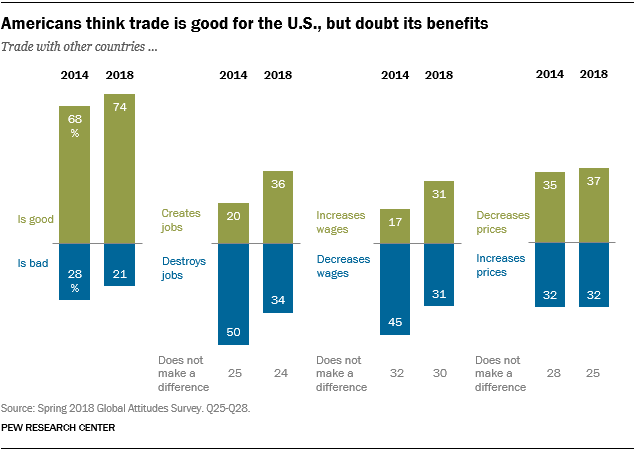

Americans also do not believe in many of the purported benefits of trade. Only 36% of Americans think trade creates jobs, 9 points lower than the view in other advanced economies and 20 points less than the median in emerging markets. And 31% of Americans expect trade to raise wages, comparable to the view in other advanced economies but less than the 48% in emerging markets who see trade boosting wages. Americans are more likely than others to believe that trade lowers prices, although just 37% in the U.S. voice that view.

The American public’s views on trade may be evolving, although not at a uniform pace. Since 2014, belief that trade creates jobs has risen (up 16 points), as has the share who say trade increases wages (up 14 points). Yet, over the same period, the view that trade decreases prices has remained essentially the same.

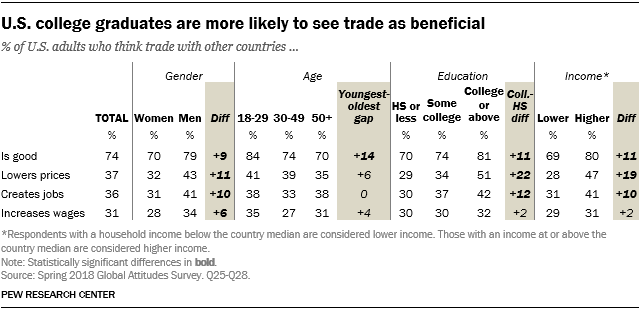

American adults differ in their views of trade by gender, age, education level and income. Men are more likely than women to believe that trade is good and that it creates jobs, boosts wages and lowers prices. Americans ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those ages 50 and older to see trade as good. Those with a college education or more are significantly more likely than those with a high school education or less to believe that trade lowers prices and creates jobs.

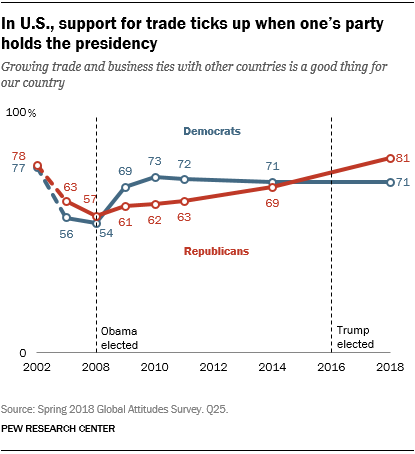

Even though they generally see trade in a positive light, Americans also view trade through an increasingly partisan lens. In 2002, Republicans and Democrats agreed overwhelmingly that trade was good for the U.S. By 2009, a larger share of Democrats than Republicans viewed trade positively. And by 2018 the partisan gap had flip-flopped, with Republicans more affirmative about trade. It is noteworthy that Democrats became more positive when Democrat Barack Obama became president and Republicans became more upbeat when their party’s candidate, Donald Trump, was elected.

Even though they generally see trade in a positive light, Americans also view trade through an increasingly partisan lens. In 2002, Republicans and Democrats agreed overwhelmingly that trade was good for the U.S. By 2009, a larger share of Democrats than Republicans viewed trade positively. And by 2018 the partisan gap had flip-flopped, with Republicans more affirmative about trade. It is noteworthy that Democrats became more positive when Democrat Barack Obama became president and Republicans became more upbeat when their party’s candidate, Donald Trump, was elected.

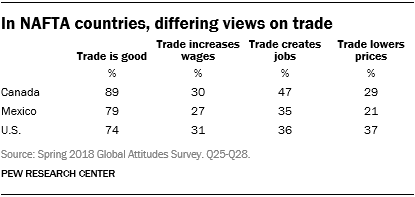

Against this backdrop, the United States, Canada and Mexico are engaged in a renegotiation of their North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Their publics overwhelmingly think trade is good for their countries, in principle. But, in practice, in no NAFTA nation do a majority of adults believe that trade creates jobs, raises wages or lowers prices. Canadians are more likely than Americans and Mexicans to say that trade generates jobs. And Canadians and Mexicans are less likely than Americans to hold the view that trade lowers prices.

Against this backdrop, the United States, Canada and Mexico are engaged in a renegotiation of their North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Their publics overwhelmingly think trade is good for their countries, in principle. But, in practice, in no NAFTA nation do a majority of adults believe that trade creates jobs, raises wages or lowers prices. Canadians are more likely than Americans and Mexicans to say that trade generates jobs. And Canadians and Mexicans are less likely than Americans to hold the view that trade lowers prices.

Europeans divided on the benefits of trade

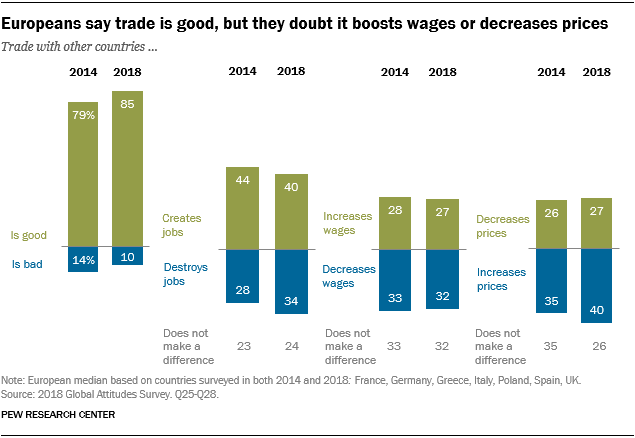

More than eight-in-ten Europeans say trade is good for their country. Such sentiment is up slightly from 2014. Four-in-ten Europeans say international commerce creates jobs, while about a third believe trade leads to job losses. Roughly a third also hold the view that trade undermines wages, more than the share who think it leads to wage increases. And, notably, nearly four-in-ten think trade leads to price increases, significantly more than the portion of Europeans who hold that it contributes to price decreases.

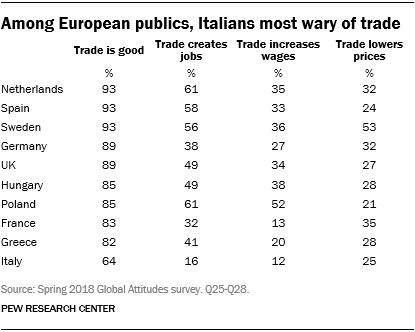

There is little difference among Europeans, with the exception of Italians, about the value of growing trade and business ties between countries. There are more significant differences between countries of the European Union on the impact of trade.

While 61% of Dutch and Poles say trade creates jobs, just 32% of French and 17% of Italians agree. Such sentiment is largely unchanged in most European nations since 2014, although belief that trade creates jobs is up in Poland by 10 points. The share of Poles saying trade raises wages is also up 14 points, while it has remained steady elsewhere. And while roughly half of Swedes think trade lowers prices, a quarter or fewer of Italians, Spanish and Poles agree.

While 61% of Dutch and Poles say trade creates jobs, just 32% of French and 17% of Italians agree. Such sentiment is largely unchanged in most European nations since 2014, although belief that trade creates jobs is up in Poland by 10 points. The share of Poles saying trade raises wages is also up 14 points, while it has remained steady elsewhere. And while roughly half of Swedes think trade lowers prices, a quarter or fewer of Italians, Spanish and Poles agree.

Notably, trade skepticism is not a defining sentiment among supporters of populist parties in most European nations, with some exceptions. Supporters of the Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands are less likely than others to believe that trade creates jobs or raises wages. And in France, those who back National Rally (formerly known as the National Front) are more likely to voice the view that trade destroys jobs and increases prices than are others.

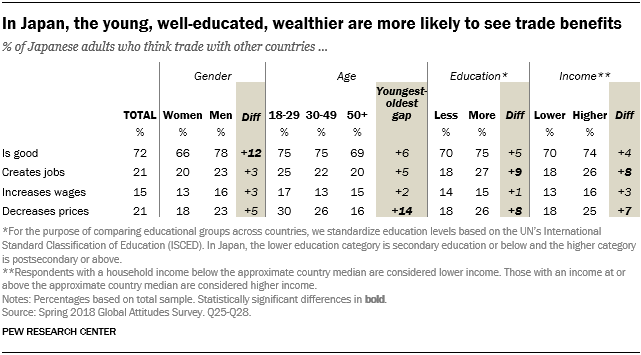

Japanese support trade, but are wary of its impact on prices

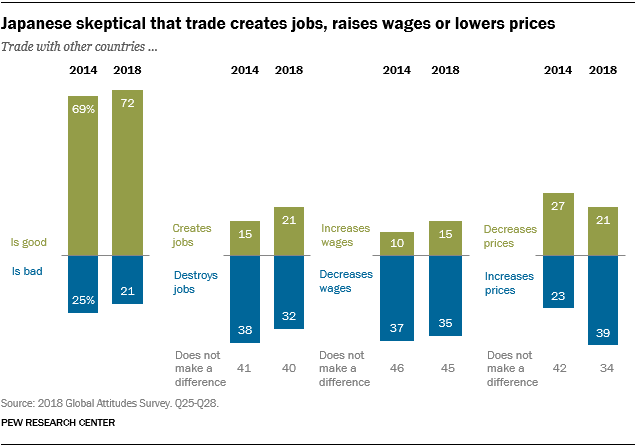

Like most Americans and Europeans, seven-in-ten Japanese adults believe that growing trade and business ties between Japan and other countries is a good thing. Such views have not changed much in the past four years. About a third of Japanese are of the opinion that trade kills jobs, while fewer say it creates jobs. But the share of Japanese blaming trade for job losses has declined since 2014. And by more than two-to-one, Japanese assert that trade leads to wage decreases rather than wage increases.

The most significant change in Japanese public opinion regarding trade has to do with its impact on prices. Roughly four-in-ten Japanese adults think trade leads to price increases, nearly double the share who says it lowers prices. And that portion has grown by 16 percentage points since 2014, despite the fact that Japan’s inflation rate has hovered below 1% for years.

Japanese men are more likely than women to believe that trade is good for Japan. Three-in-ten Japanese ages 18 to 29 say trade lowers prices, around twice the share of their elders, those ages 50 and older, who credit trade with restraining inflation. Japanese with a postsecondary education or more and an income above the national median are more likely than others to say trade lowers prices and creates jobs.