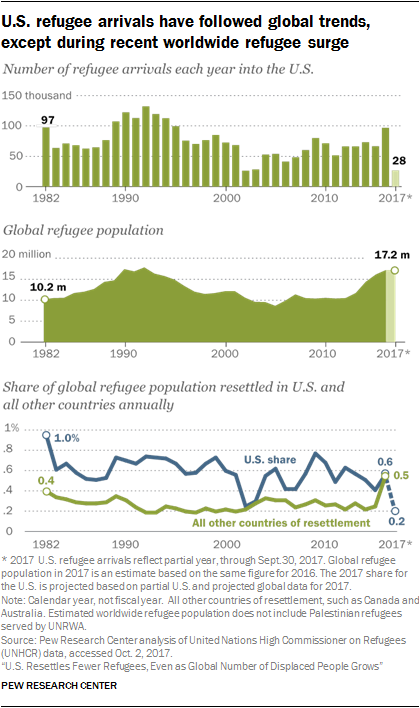

The U.S. has resettled more refugees than any other country – about 3 million since 1980. Generally, in years when more people around the globe are displaced by conflict, violence or persecution in their countries, the number of refugees resettled by the U.S. has increased. But in the last few years, the number of refugees annually resettled by the U.S. has not consistently grown in step with a worldwide refugee population that has expanded nearly 50% since 2013, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and U.S. State Department data.

Across the globe in 2016, there were about 17.2 million people displaced from their homes due to conflict or persecution across international borders, according to UNHCR.1 That is a new global high point that rivals the early 1990s, following the fall of the Berlin Wall. On average, between 1982 and 2016, the U.S. resettled about 0.6% of the globe’s total refugee population each year.

Across the globe in 2016, there were about 17.2 million people displaced from their homes due to conflict or persecution across international borders, according to UNHCR.1 That is a new global high point that rivals the early 1990s, following the fall of the Berlin Wall. On average, between 1982 and 2016, the U.S. resettled about 0.6% of the globe’s total refugee population each year.

Each year, UNHCR identifies a portion of all officially recognized refugees as candidates for resettlement in the U.S. or other countries. In recent years, about 1 million individuals per year have been identified for resettlement. Of this number, only a fraction of refugees are typically resettled. In 2016, for example, out of approximately 1 million eligible refugees identified by UNHCR, an estimated 189,000 were resettled worldwide, with more than half (51%) of these ending up in the United States. Between 1982 and 2016, the U.S. admitted more than two-thirds (69%) of the world’s resettled refugees, followed by Canada (14%) and Australia (11%).2

For several decades, the annual volume of U.S. refugee arrivals has generally waxed and waned with the world’s overall refugee population.3 For example, when the global number of refugees peaked in 1992 at 17.8 million, the number of refugees resettled by the U.S. also increased, reaching a high of about 132,000 that year.4 And in the early-to-mid 2000s, as the number of displaced people worldwide fell to less than 10 million, the number of refugees entering the U.S. also decreased, falling to an average of about 50,000 or less annually. This decline reflected a global decrease in the number of displaced people, as well as post-9/11 changes in the way the U.S. vetted asylum seekers. The U.S. administration in 2017 is again reviewing security screening procedures for all immigrant admissions, including refugees.5

After holding fairly steady between 2012 and 2015, the annual number of refugees resettled in the U.S. jumped to 97,000 in 2016, according to UNHCR data. In part, this was the Obama administration’s response to a dramatic increase in the global number of displaced people due to conflicts in Syria, Iraq and sub-Saharan Africa. Even with the 2016 increase, however, the number of refugees resettled in the U.S. during the latter years under President Barack Obama was lower than in previous times of high refugee resettlement in the U.S. and did not keep pace with the world’s refugee population. Annual admissions from 2014 onward would have had to exceed well over 100,000 refugees to emulate past American responses to refugee surges, such as in the early 1990s.

Thus far in 2017, about 28,000 refugees have been resettled in the U.S., far less than in 2016, according to U.S. State Department data. If the number of refugees worldwide remains the same as in 2016 and if few refugees enter the U.S. for the rest of 2017, the U.S. is on track to accept just 0.2% of the world’s refugee population – far less than the historic average of 0.6%, and lower even than the share admitted in 2001 and 2002, in the wake of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

Each year, the president’s administration sets the ceiling for how many refugees are resettled in the United States. In fiscal 2017, the Trump administration used an executive order to reduce the number of refugee admissions previously set by the outgoing Obama White House to be less than half the initial ceiling.6 Looking ahead to fiscal 2018, the Trump administration has proposed a refugee resettlement ceiling of 45,000 to Congress. The White House has also asked Congress for lower annual admissions of refugees as part of their immigration principles for immigration legislation.

How it works: The U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program

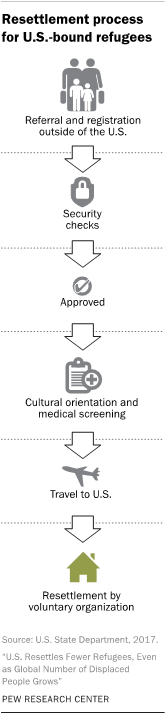

All refugees are processed and approved outside of the United States. Refugee applicants are referred to U.S. officials by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), U.S. embassies and nongovernmental organizations. Applications are screened by the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and other federal agencies for any security concerns.

All refugees are processed and approved outside of the United States. Refugee applicants are referred to U.S. officials by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), U.S. embassies and nongovernmental organizations. Applications are screened by the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and other federal agencies for any security concerns.

Many refugees are not processed in their countries of citizenship. They are often waiting for resettlement in a nearby country where they have taken temporary refuge, sometimes for several years. While awaiting resettlement, refugees undergo health screenings and cultural orientations before entering the U.S. It is a process that can take between 18 and 24 months to complete. (For a more detailed explanation of the application and approval process, visit the U.S. State Department’s website.)

The International Organization for Migration and U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement work with U.S. based voluntary agencies like the International Rescue Committee or Church World Service to resettle refugees within the U.S. These voluntary agencies have offices across the nation, dispersing refugees across many states. Once resettled, local nonprofits, such as ethnic associations and church-based groups, help refugees learn English and acquire job skills. After several months, financial assistance from federal agencies stops and refugees are expected to become financially self-sufficient. In a short period of time, most refugee households have employed members. U.S. refugees are granted permanent residency within a year of arrival and can apply for U.S. citizenship five years later.

Worldwide, the U.S. has formally resettled more refugees than any other country, according to UNHCR. Refugee arrivals do not include asylum seekers already living in the U.S. or those appearing at the U.S. border claiming asylum, such as the thousands of unaccompanied minors from Central America who have entered the U.S. in recent years. Compared with those seeking refuge on Europe’s shores, the U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program is a different pathway for those fleeing conflict. For example, the more than 1.3 million refugees entering Europe in 2015 were asylum seekers, not resettled refugees. They sought refuge in Europe on their own after arriving in Europe and were not formally resettled by European countries. They will wait for decisions on their asylum applications while living in Europe.

Profile of U.S. refugee arrivals: Changes and trends

Note: Data analyses from this point forward in the report are for fiscal years (Oct. 1 to Sept. 30)

Nationality of U.S. refugees: Middle East and Africa are on the rise

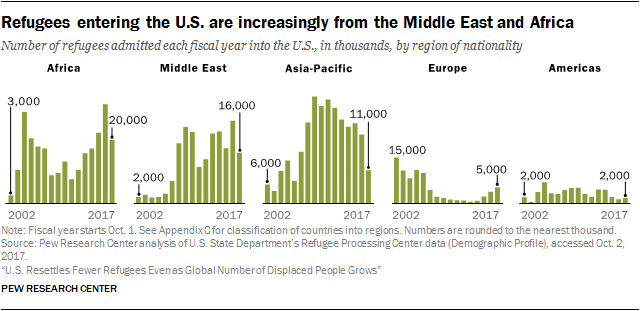

The nationalities of refugees resettled in the U.S. have changed over the past decade and a half, with an increasing number from Middle Eastern and African countries. In fiscal 2002 – the earliest year for which we have detailed data on U.S. refugee arrivals – 17% of refugees entering the U.S. (nearly 5,000) were from Middle Eastern and African countries. By fiscal 2017, that share had grown to more than two- thirds (68%, or slightly more than 36,000) of U.S. refugee arrivals, reflecting a similar rise of the number of refugees from these parts of the world in the global refugee population.

By contrast, Europe used to be the primary region of nationality for resettled refugees during the early 2000s. In fiscal 2002, for example, more than half (54% or nearly 15,000) of refugees admitted into the U.S. were citizens of European countries. That share, however, dropped to 9% of refugee arrivals, or about 5,000 refugees, in fiscal 2017.

Starting in fiscal 2006, refugees from the Asia-Pacific region also saw their numbers and share increase for several years. Between 2008 and 2012, for example, more than four-in-ten refugees entering the U.S. each year were from Asian countries, with most from Burma (Myanmar) and Bhutan, countries the U.S. prioritized for several years in its refugee resettlement policies. Refugees from these two countries continue to enter the U.S., but in the past couple of years they have done so in lower numbers.

Starting in fiscal 2006, refugees from the Asia-Pacific region also saw their numbers and share increase for several years. Between 2008 and 2012, for example, more than four-in-ten refugees entering the U.S. each year were from Asian countries, with most from Burma (Myanmar) and Bhutan, countries the U.S. prioritized for several years in its refugee resettlement policies. Refugees from these two countries continue to enter the U.S., but in the past couple of years they have done so in lower numbers.

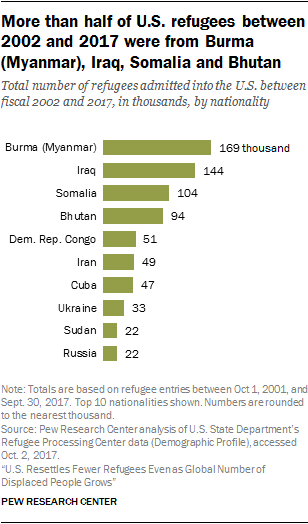

Between fiscal 2002 and 2017, 55% of refugees entering the U.S. came from Burma (Myanmar), Iraq, Somalia or Bhutan.7 More than 169,000 refugees since fiscal 2002 have come to the U.S. from Burma (Myanmar) – more than any other country. Some 144,000 have come from Iraq, while nearly 104,000 have been Somalis. Almost 94,000 Bhutanese refugees have entered the U.S. since 2002.

Although more than 21,000 Syrian refugees have entered the U.S. since 2002, they do not appear in the top 10 nationalities of U.S. refugees. Most did not enter the U.S. until fiscal 2016 and 2017.

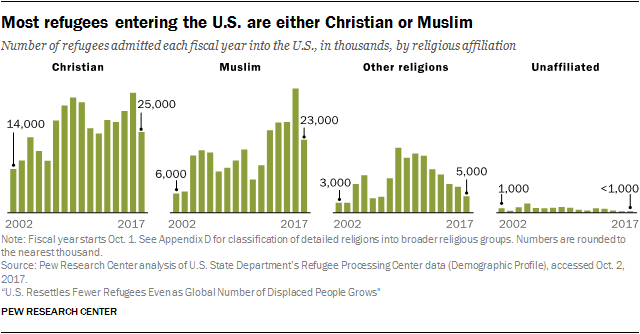

Religious affiliation of U.S. refugees: Growing number of Muslims

As nationalities of refugees have changed, so too have religious affiliations. Between fiscal 2011 and 2016, a rising number of refugees have been Muslim, reflecting the increasing number of refugees from Muslim-majority countries admitted to the United States. In 2016, a record number of Muslim refugees were admitted to the U.S.

At the same time, Christians continue to make up a large share of the refugees admitted to the United States. In fiscal 2017, for example, a plurality of refugee arrivals were Christian (47%), with Muslims (43%) representing the second largest religious group.

In recent years, the share of refugees entering the U.S. who are affiliated with religions other than Christianity and Islam has declined. But from 2009 to 2012, between about a quarter and a third of refugees entering each year were adherents of other religions, including several thousand Hindus (mostly from Bhutan) and Buddhists (mostly from Burma and Bhutan).

Refugees with no religious affiliation were 5% of all refugees admitted to the U.S. in fiscal 2002. Since then, the share of refugees with no religious affiliation has decreased, amounting to less than 1% of refugees entering the U.S. during fiscal 2017.

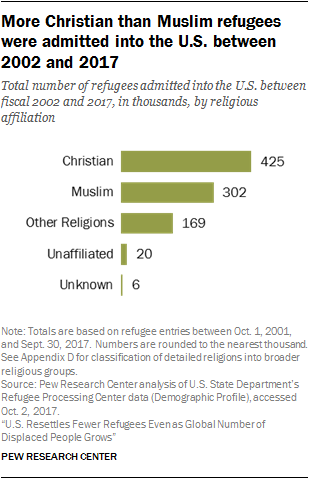

Even with the recent rise in the number of Muslim refugees, far more Christian than Muslim refugees have been admitted into the U.S. since fiscal 2002. Nearly 425,000 Christian refugees entered the U.S. over that period, accounting for 46% of all refugee arrivals. At the same time, about a third (33%) of all refugees admitted to the U.S. between 2002 and 2017, or slightly more than 302,000, were Muslim.

Even with the recent rise in the number of Muslim refugees, far more Christian than Muslim refugees have been admitted into the U.S. since fiscal 2002. Nearly 425,000 Christian refugees entered the U.S. over that period, accounting for 46% of all refugee arrivals. At the same time, about a third (33%) of all refugees admitted to the U.S. between 2002 and 2017, or slightly more than 302,000, were Muslim.

Some 169,000 refugees belonging to other religions entered the U.S. during the same time period, with about 55,000 claiming Hindu religious identity (mostly from Bhutan) and about 50,000 additional refugees claiming Buddhist religious identity (mostly from Burma and Bhutan).

More than 20,000 refugees with no religious affiliation have entered the U.S. between fiscal 2002 and 2017, mostly from Cuba and Vietnam.

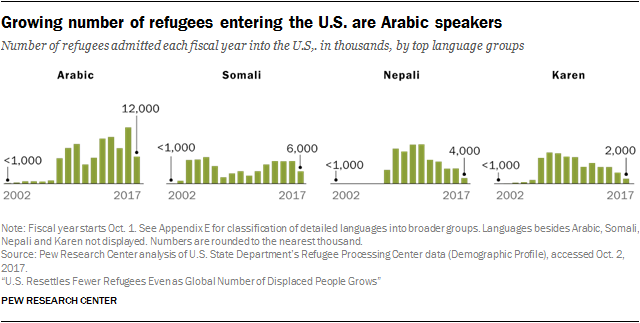

Language of U.S. refugees: Arabic is now the most spoken language among newly admitted refugees

With the rise of U.S. refugee arrivals from Middle Eastern and African countries, Arabic has become the most spoken language of incoming refugees. In fiscal 2017, nearly a quarter of refugees entering the U.S. (23%, or more than 12,000 people) spoke Arabic; most of them came from Syria and Iraq.

As the number of Arabic-speaking refugee arrivals has grown in recent years, no other single language has accounted for as high a number of total refugee admissions into the U.S. since 2002.

In all, more than 143,000 refugees entering the U.S. between 2002 and 2017 spoke Arabic.

The rise of Arabic as a leading language of U.S. refugees was preceded by high shares of refugees speaking Somali. In 2004 through 2006, Somali was the leading language of refugees entering the U.S. Overall, between 2002 and 2017, more than 95,000 Somali-speaking refugees entered the U.S.

In 2007, Karen, a language spoken by most refugees from Burma (Myanmar), was the top language of refugees. In total, more than 73,000 refugees entered the U.S. between 2002 and 2017 speaking various Karen dialects.

In fiscal 2011 and 2012, the top language became Nepali, the majority language of refugees from Bhutan. In all, more than 94,000 Nepali-speaking refugees entered the U.S. between 2002 and 2017.

Demographics of U.S. refugees: Plurality have been children and adolescents, more have been male than female

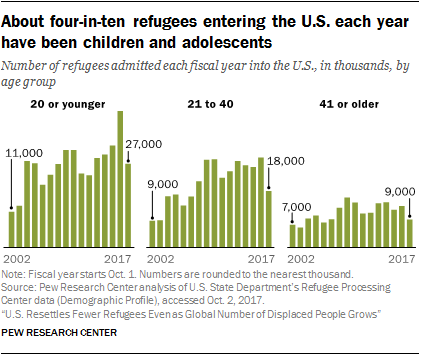

For most years between 2002 and 2017, the annual share of refugees entering the U.S. ages 20 or younger was between about 40% and 50% of all refugees. Given this age profile, local schools can play a significant role in how younger refugees learn English and acclimate to U.S. society.

Roughly a third of refugees entering the U.S. annually between 2002 and 2017 were younger adults, ages 21 through 40. About another 20% of admitted refugees each year were 41 years or older.

Data on the age composition of the global refugee population is incomplete, but estimates suggest that the majority of refugees worldwide are children and adolescents below the age of 18. Consequently, a high share of children and adolescent refugees entering the U.S. each year is consistent with the makeup of refugees worldwide.

Data on the age composition of the global refugee population is incomplete, but estimates suggest that the majority of refugees worldwide are children and adolescents below the age of 18. Consequently, a high share of children and adolescent refugees entering the U.S. each year is consistent with the makeup of refugees worldwide.

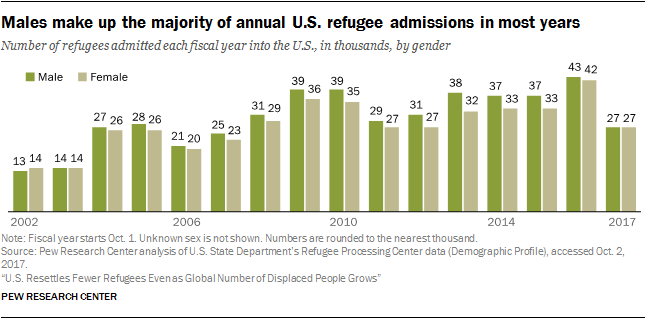

Between 2003 and 2016, men have made up more than half of refugees entering the U.S. each year, with the male share peaking at 54% in 2013.8 Refugees worldwide also lean more male than female. By fiscal 2017, however, men and women made up nearly equal shares of refugees entering the United States.

Destinations of U.S. refugees: A handful of states accept most refugees

With refugee resettlement organizations scattered throughout the country, U.S. refugees have been resettled in almost every state. Even so, just a handful of states have accepted the majority of U.S. refugees.

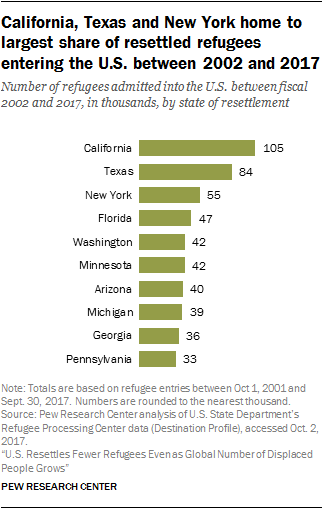

The three most populated U.S. states – California, Texas and New York – have taken in more than a quarter (27%) of refugees entering the U.S. since 2002. Other top states for total refugee resettlement between fiscal 2002 and 2017 include Florida (more than 47,000), Washington (nearly 42,000) and Minnesota (more than 41,000). In all, more than half (57%) of refugees entering the U.S. since 2002 have settled in the top 10 states for refugee resettlement.

The three most populated U.S. states – California, Texas and New York – have taken in more than a quarter (27%) of refugees entering the U.S. since 2002. Other top states for total refugee resettlement between fiscal 2002 and 2017 include Florida (more than 47,000), Washington (nearly 42,000) and Minnesota (more than 41,000). In all, more than half (57%) of refugees entering the U.S. since 2002 have settled in the top 10 states for refugee resettlement.

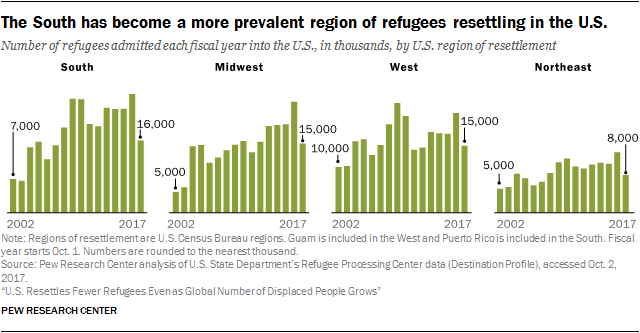

Regionally, more than a quarter of refugees entering the U.S. between fiscal 2002 and 2017 were resettled in each of the following regions: Southern states (including top states Texas and Florida), Western states (including top states California and Washington), and Midwestern states (including top states Minnesota and Michigan). The remainder of refugees (16%) entering the U.S. between 2002 and 2017 were resettled in Northeastern states (including top states New York and Pennsylvania).9

Southern states have seen the most notable increase in the annual share of resettled refugees in the United States.10 About 15 years ago, about a quarter of all refugees were resettled in Southern states each year. But the share grew to become 32% of all resettled refugees in fiscal 2015 and 29% in fiscal 2017.

Where have refugees settled in the U.S.?

Where have refugees settled in the U.S.?