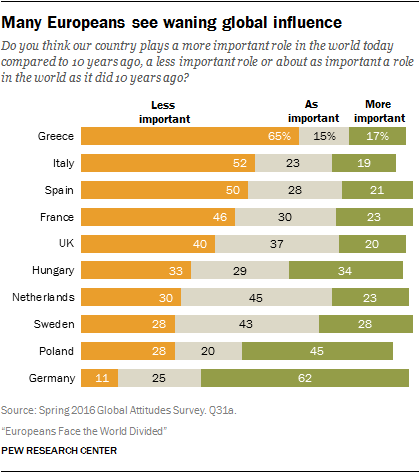

Some Europeans are experiencing a crisis of confidence about their nations’ role in the world. Among countries surveyed, only in Germany and Poland do a majority or plurality (62% and 45% respectively) believe their country plays a more important role in the world today compared with 10 years ago. About two-thirds (65%) of Greeks, roughly half of Italians (52%) and Spanish (50%), and a plurality of the French (46%) say their nations now play a less important part on the world stage. The Dutch (45%) and Swedes (43%) hold the view that their countries enjoy as important a role as they did a decade ago.

A majority of Germans of all ages express the opinion that Germany is now more powerful. In Poland, about half the young (52%) see their country as more important, but only 37% of those ages 50 and older agree. In contrast, young, middle-aged and older people in Italy, Greece and Spain all believe that their nation is less important than it was 10 years ago.

Against a backdrop of a perceived decline in global stature many Europeans are looking inward. Fully 83% of Greeks, 77% of Hungarians, 67% of Italians and 65% of Poles believe their countries should deal with their own problems and let other nations deal with their own problems as best they can. The French (60%), British (52%) and Dutch (51%) tend to agree that their nations should just deal with their own problems.

Only in Spain (55%), Germany (53%) and Sweden (51%) do half or more support their country helping other nations. Just 12% of Greeks, 18% of Hungarians, 21% of Poles and 22% of Italians express the view that they should come to the assistance of others.

Ideology divides many Europeans on this issue of global engagement. In eight of 10 EU nations surveyed people on the right of the political spectrum are more likely than those on the left to say their country should focus on domestic problems rather than help others. This is a particularly strong view held by the Greek right (88%), the Italian right (79%) and the French right (72%). At the same time, those on the left in Germany (70%), Sweden (66%) and the Netherlands (65%) especially favor helping other countries with their problems.

Older Europeans also tend to be more inward looking than younger ones. Among those who favor dealing with their own problems, there is a 17-percentage-point generation gap in the UK between those ages 50 and older, who are more inward looking, and their countrymen ages 18 to 34. A similar 16-point divide exists in Sweden and the Netherlands, a 14-point division in Italy and a 12-point generation gap in Greece.

Support for multilateralism far from universal

A commitment to multilateralism was a bitter lesson Europe learned from two world wars. It was one of the reasons European nations were founding members of both the United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. But today, public commitment to this ideal is far from robust.

A commitment to multilateralism was a bitter lesson Europe learned from two world wars. It was one of the reasons European nations were founding members of both the United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. But today, public commitment to this ideal is far from robust.

In just three of 10 EU nations does half or more of the public subscribe to the view that in foreign policy their country should take into account the interests of allies even if it means making compromises. Only Germans (67%) are strongly committed to such multilateralism. Just over half the Swedes (54%) and half the Dutch agree.

At the same time 74% of Greeks, 54% of the British, 52% of the French, 51% of Hungarians and 50% of Italians say that in foreign affairs it would best if their countries followed their own national interests, even when allies strongly disagree.

At the same time 74% of Greeks, 54% of the British, 52% of the French, 51% of Hungarians and 50% of Italians say that in foreign affairs it would best if their countries followed their own national interests, even when allies strongly disagree.

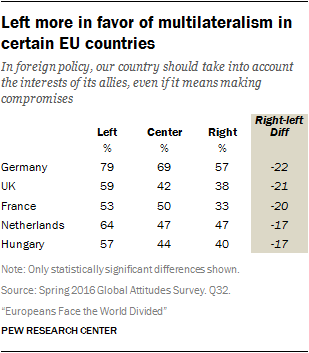

Again this is an ideologically divisive issue in a number of European societies. In Germany 79% of people on the left think Berlin should compromise with its allies, compared with 57% of Germans on the right. There is a similar left-right split of 21 points in the UK (59% to 38%) and 20 points in France (53% to 33%).

Despite criticism, aspirations for an influential EU

Europeans are dissatisfied with the European Union, which has responsibility for Europe’s trade relations with the rest of the world and a growing role in European foreign policy. Yet a plurality of Germans, Hungarians, Italians, Dutch, Poles, Swedes and British believe that the EU plays a more important role in the world today than it did a decade ago. And by huge margins, in all the EU member states surveyed publics want the EU to play a more active role in world affairs than it does today.

A median of just 51% hold a favorable view of the Brussels-based institution. The most unhappy are the Greeks (27%), French (38%), British (44%) and Spanish (47%). And favorable opinion of the EU is down in five of the six nations surveyed in both 2015 and 2016.

Europeans are quite critical of the EU’s current handling of the refugee situation, relations with Russia and European economic problems.

Overwhelming majorities disapprove of the EU’s management of the refugee crisis. Fully 94% of Greeks, 88% of Swedes, 77% of Italians, and 75% of Spanish disapprove of the EU’s efforts. Roughly seven-in ten Hungarians, Poles, British and French take the same position.

Overwhelming majorities disapprove of the EU’s management of the refugee crisis. Fully 94% of Greeks, 88% of Swedes, 77% of Italians, and 75% of Spanish disapprove of the EU’s efforts. Roughly seven-in ten Hungarians, Poles, British and French take the same position.

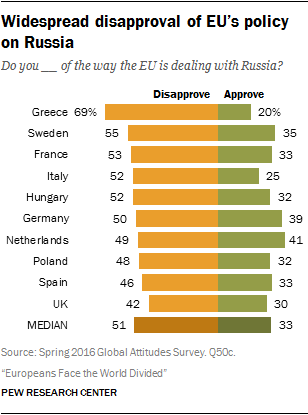

Majorities or pluralities in all the EU member states surveyed disapprove of the job being done by the institution in dealing with Russia. The strongest criticism comes from Greece (69%), Sweden (55%), France (53%), Italy and Hungary (both 52%).

Europeans are divided about how to treat Russia going forward. About nine-in-ten Greeks believe it is more important to have a strong economic relationship with Russia than to be tough with Moscow on foreign policy disputes. Smaller majorities of Hungarians (67%), Germans (58%) and Italians (54%) agree. Swedes (71%) say being tough is more important, while other European countries are split.

Europeans are divided about how to treat Russia going forward. About nine-in-ten Greeks believe it is more important to have a strong economic relationship with Russia than to be tough with Moscow on foreign policy disputes. Smaller majorities of Hungarians (67%), Germans (58%) and Italians (54%) agree. Swedes (71%) say being tough is more important, while other European countries are split.

Europeans are also unhappy with the EU’s handling of economic problems. About nine-in-ten Greeks (92%) disapprove of how the EU has dealt with the issue. Roughly two-thirds of Italians (68%), French (66%) and Spanish (65%) similarly disapprove. (France and Spain are the two nations where the favorability of the EU has recently experienced the largest decline.) Majorities in Sweden (59%) and the UK (55%) – the latter includes 84% of UKIP supporters – also disapprove of the EU’s job in dealing with economic challenges. The strongest approval of Brussels’ economic efforts is in Poland and Germany (both 47%).

At a time when Europeans are generally downbeat about the EU’s recent international record, many see the EU playing a larger role in the world. Roughly half the Dutch (51%) and the Swedes (49%) say the EU is more important today than it was a decade ago. And a plurality of Germans (46%), Hungarians (43%), Poles (42%), Italians (41%) and British (39%) agree.

In several societies it is young people (those ages 18 to 34) more than older people (those 50 and older) who see Brussels playing a larger international role today. Such a generational gap exists in Germany, Poland, Sweden, and the UK.

And a median of 74% of Europeans want the EU to take a more active international stance in the years ahead. Only in the UK (33%) and the Netherlands (31%) is there a sizable minority that favors the EU playing a less active role in the future.

Such public sentiments illustrate a contrast between a fairly negative assessment of the EU’s handling of key problems and public hopes for the EU’s future role in the world. This may in part be explained by people’s idealism about the EU’s potential. A 2014 Pew Research Center survey found that strong majorities in six EU nations believed the EU promotes peace.

Europeans are quite supportive of the United Nations. A median of 66% hold a favorable view of the New York-based international institution. This includes roughly eight-in-ten Swedes (82%), seven-in-ten Dutch (72%) and about two-thirds of the British (68%) and Germans (65%). Notably, just 41% of Greeks are positively disposed toward the UN, the lowest rating in Europe.

But the generally pro-UN sentiment is slipping in a number of EU nations. The recent high point in favorable rating for the UN was in 2011 in France, Spain and the UK. Since then support is down in all these countries.

Views of the UN do not neatly track with ideological orientation. People on the left in Germany are more likely than those on the right to hold a positive view of the UN. In France, Greece and Spain those on the right are more favorably disposed toward the organization.

There is also widespread European support for NATO, the post-World War II security alliance. A median of 59% say they have a favorable opinion of the multilateral institution (nine of the 10 European nations in the survey are members, Sweden is not). The strongest support is in the Netherlands (71%) and Poland (70%).

There is also widespread European support for NATO, the post-World War II security alliance. A median of 59% say they have a favorable opinion of the multilateral institution (nine of the 10 European nations in the survey are members, Sweden is not). The strongest support is in the Netherlands (71%) and Poland (70%).

The lowest rating for the military partnership is in Greece (25%). There has been a drop-off in French backing, from 64% in 2015 to 49% in 2016, although this may be attributable to a rise in the number of people who express no opinion.

The Swedes have long debated joining NATO, and 58% have a favorable view of the organization. But the Swedish public is split on membership: 45% say they back the country becoming a NATO member, while 44% oppose such a move.

In most European countries surveyed there is not an overwhelming ideological difference of opinion regarding NATO. However the left-right splits are quite large in Sweden (72% favorable on the right, 35% on the left) and Spain (56% positive on the right, 27% on the left).

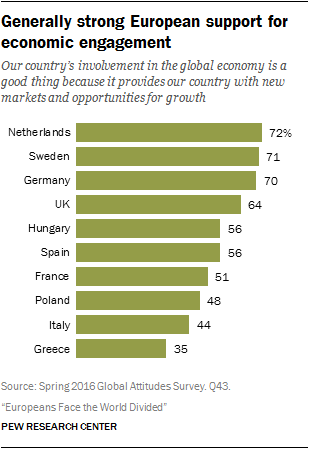

European economies are deeply dependent on international commerce, and most Europeans have supported international trade in recent years. Roughly half or more of those in eight of the 10 EU nations surveyed believe their involvement in the global economy is a good thing because it provides their country with new markets and opportunities for growth. The Dutch (72%), Swedes (71%) and Germans (70%) are the strongest supporters of such engagement. By contrast, less than half of Italians (44%) and only about a third of Greeks (35%) are positive about their countries’ role in the world economy.

European economies are deeply dependent on international commerce, and most Europeans have supported international trade in recent years. Roughly half or more of those in eight of the 10 EU nations surveyed believe their involvement in the global economy is a good thing because it provides their country with new markets and opportunities for growth. The Dutch (72%), Swedes (71%) and Germans (70%) are the strongest supporters of such engagement. By contrast, less than half of Italians (44%) and only about a third of Greeks (35%) are positive about their countries’ role in the world economy.

Those with a better education are significantly more likely than the less-educated to think involvement in the global economy is a good thing in six of the EU countries surveyed. And the differences in opinion can be quite high: 28 points in the Netherlands, 20 points in Spain and 17 points in France.