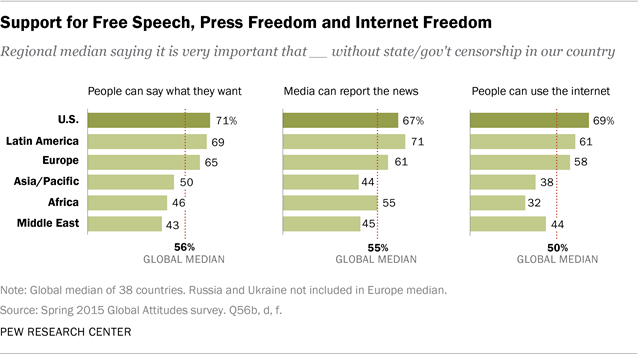

Although many observers have documented a global decline in democratic rights in recent years, people around the world nonetheless embrace fundamental democratic values, including free expression. A new Pew Research Center survey finds that majorities in nearly all 38 nations polled say it is at least somewhat important to live in a country with free speech, a free press and freedom on the internet. And across the 38 countries, global medians of 50% or more consider these freedoms very important.

Still, ideas about free expression vary widely across regions and nations. The United States stands out for its especially strong opposition to government censorship, as do countries in Latin America and Europe – particularly Argentina, Germany, Spain and Chile. Majorities in Asia, Africa and the Middle East also tend to oppose censorship, albeit with much less intensity. Indonesians, Palestinians, Burkinabe and Vietnamese are among the least likely to say free expression is very important.

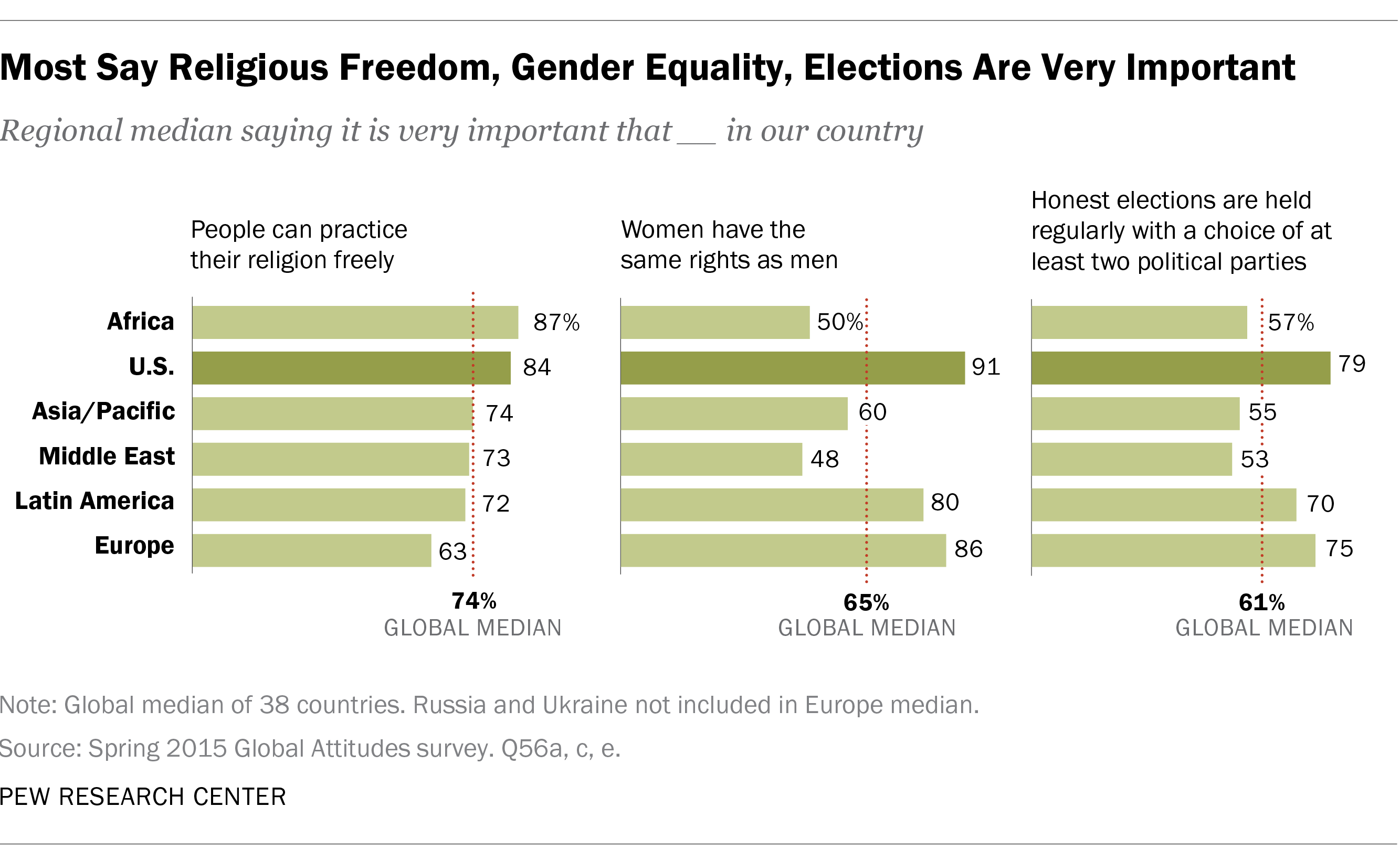

While free expression is popular around the globe, other democratic rights are even more widely embraced. In Western and non-Western nations, throughout the global North and South, majorities want freedom of religion, gender equality, and honest, competitive elections. Yet the strength of commitment to individual liberties also varies. Americans are among the strongest supporters of these freedoms. Meanwhile, Europeans are especially likely to want gender equality and competitive elections, but somewhat less likely than others to prioritize religious freedom. The right to worship freely is most popular in sub-Saharan Africa. Across all regions, people who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely to value religious freedom.

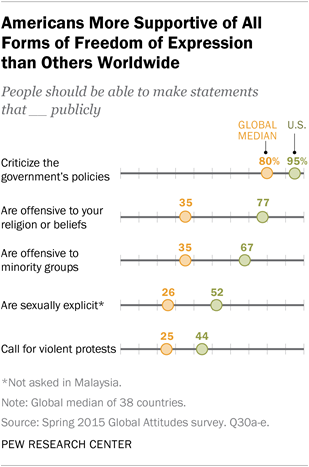

Even though broad democratic values are popular, people in different parts of the world have different ways of conceptualizing individual rights and the parameters of free expression. Publics tend to support free speech in principle, but they also want limitations on certain types of speech. While a global median of 80% believe people should be allowed to freely criticize government policies, only 35% think they should be allowed to make public statements that are offensive to minority groups, or that are religiously offensive. Even fewer support allowing sexually explicit statements or calls for violent protests.

Even though broad democratic values are popular, people in different parts of the world have different ways of conceptualizing individual rights and the parameters of free expression. Publics tend to support free speech in principle, but they also want limitations on certain types of speech. While a global median of 80% believe people should be allowed to freely criticize government policies, only 35% think they should be allowed to make public statements that are offensive to minority groups, or that are religiously offensive. Even fewer support allowing sexually explicit statements or calls for violent protests.

Americans, however, are more willing than the rest of the world to tolerate these forms of speech. Large majorities in the U.S. think people should be able to say things that are offensive to minority groups or their religious beliefs. About half (52%) say this about sexually explicit statements, and more than four-in-ten (44%) think calls for violent protests should be allowed.

These are among the main findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted in 38 nations among 40,786 respondents from April 5 to May 21, 2015.

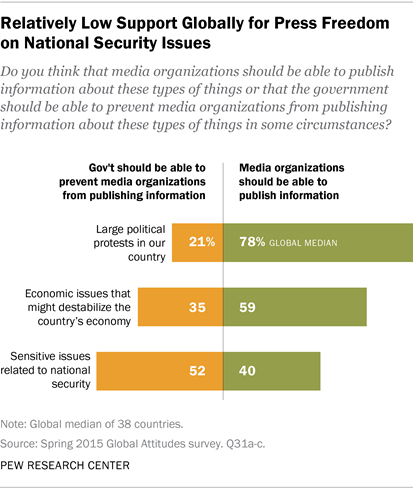

When Can Government Stop the Media from Publishing?

Overall, global publics oppose government censorship of the media, except in cases of national security. There is widespread agreement that media organizations should be able to publish information about large political protests in the country – across the nations polled, a median of 78% say this. Vietnam is the only country where fewer than half (42%) hold this view.

Overall, global publics oppose government censorship of the media, except in cases of national security. There is widespread agreement that media organizations should be able to publish information about large political protests in the country – across the nations polled, a median of 78% say this. Vietnam is the only country where fewer than half (42%) hold this view.

Most (a global median of 59%) also think media groups should be able to publish information that might destabilize the national economy. The Middle East is the regional outlier on this question – a median of just 44% in the region say the press should be allowed to publish economically destabilizing information, while 51% believe the government should be able to block these types of stories in some circumstances.

Globally, a median of just 40% think media organizations should be able to publish information about sensitive issues related to national security, while 52% believe it is acceptable for the government to suppress such information. But opinions vary widely across countries and regions. Latin Americans and Europeans tend to think the press should be allowed to publish sensitive national security information, while Middle Easterners, Asians and Africans mostly oppose this idea. On this issue, most Americans support government limitations on press freedom – 59% say the government should be allowed to stop this type of publication.

Ranking Countries on Support for Free Expression

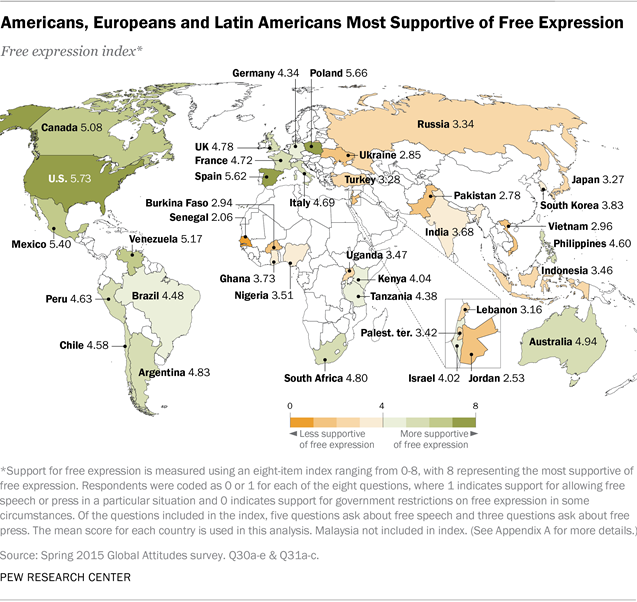

To further explore how countries compare on views about free expression, we constructed an index based on respondents’ answers to five questions about allowing specific types of speech, as well as three questions about whether the media should be allowed to publish certain types of information (see Appendix A for more details on the index).

Analyzing the data in this way reveals that Americans are the most supportive of free speech and a free press. Several European and Latin American nations also emerge as relatively strong supporters, as do Canada, Australia and South Africa. Meanwhile, Senegal, Jordan, Pakistan, Ukraine, Burkina Faso and Vietnam are at the bottom of the index, indicating relatively low levels of support for free expression.

Prioritizing Internet Freedom

In many nations the internet has created an important new public space where debates about political and social issues thrive. Even though internet freedom ranks last among the six broad democratic rights included on the survey, majorities in 32 of 38 countries nonetheless say it is important to live in a country where people can use the internet without government censorship. Across the 38 nations, a median of 50% believe it is very important to live in a country with an uncensored internet.

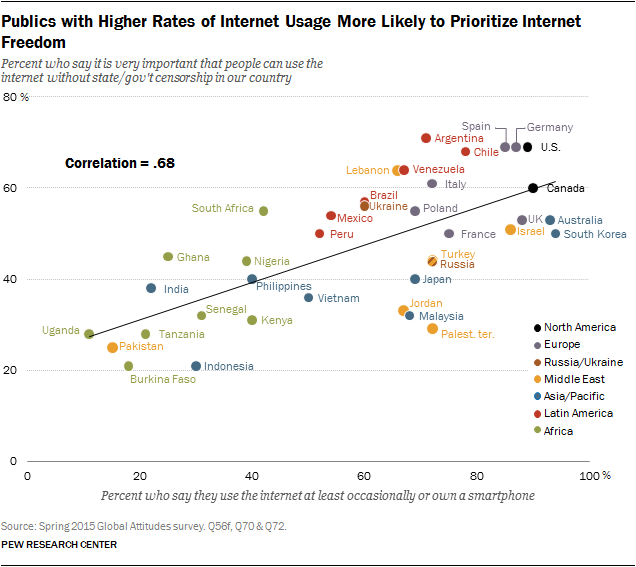

Intense support for internet freedom is highest in Argentina, the U.S., Germany and Spain – roughly seven-in-ten in these four nations consider it very important. It is lowest in Burkina Faso and Indonesia (21% very important in both countries).

Internet freedom tends to be especially important to younger people, as well as to those who say they use the internet at least occasionally or own a smartphone. There is a strong correlation between the percentage of people in a country who use the internet and the percentage who say a free internet is very important, suggesting that as access to the Web continues to spread around the globe in the coming years, the desire for freedom in cyberspace may grow as well.