In general, most publics around the world say that free speech and a free press are very important to have in their country. However, support for both is contingent on the topic of the speech. While majorities think people should be able to critique the government in public, there is less support for being able to say things that are offensive either to minorities or religious groups. And very few approve of public speech that is sexually explicit or that calls for violent protests. Widespread majorities believe the press should be able to publish information about protests in the country or economic issues that might destabilize the economy. However, with the exception of Latin American publics, relatively few support allowing the press to freely publish on sensitive issues related to national security.

Broad Support for Speech Criticizing the Government, but Not Much Else

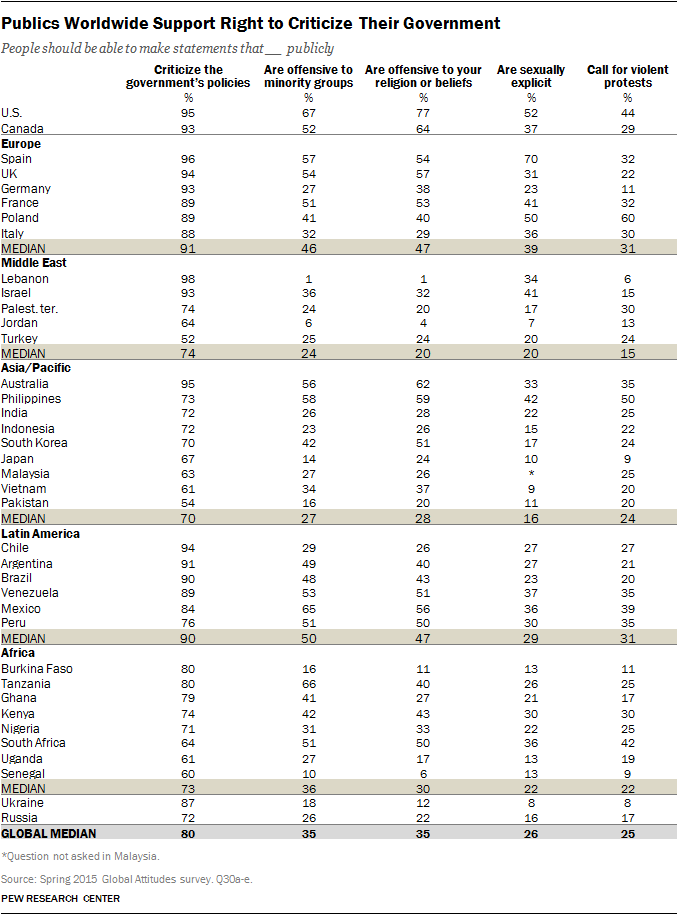

Large majorities across the globe say people should be able to criticize their government’s policies publicly without interference from the state. Opinion on this issue is especially uniform in the U.S., Canada and Europe, where roughly nine-in-ten or more in each country surveyed say people should have this right.

Publics in Latin America are also particularly supportive of being able to criticize the government, with more than eight-in-ten in most countries taking this position. Peruvians stand out as less likely to approve of this type of speech, though roughly three-quarters (76%) still say people should be able to speak out against the state.

Ukrainians also broadly think people should be able to criticize government policies in public (87%), while Russians are somewhat less likely to say the same (72%).

Other publics around the world are less supportive of publicly criticizing the government, though majorities still approve of this type of speech in many countries. Six-in-ten or more in all eight sub-Saharan African countries surveyed say people should be able to denounce government policies in public. Eight-in-ten take this position in Burkina Faso and Tanzania, with Ghana close behind at 79%. Ugandans (61%) and Senegalese (60%) are less supportive.

A median of 74% across the five Middle Eastern countries surveyed say people should be able to complain publicly about the government. This region, however, is particularly divided on the issue. More than nine-in-ten in Lebanon and Israel support criticizing the state in public. Nearly three-quarters in the Palestinian territories say the same (74%). Jordanians (64%) and Turks (52%), meanwhile, are less likely to approve. Roughly a quarter or more in Turkey (39%) and Jordan (26%) say the government should be able to prevent people from being critical of the state.

Overall, a median of 70% in the Asia-Pacific region say people should be able to denounce the government publicly. Australians stand out for being particularly supportive (95%), while Pakistanis express the lowest level of approval of this type of speech (54%).

When it comes to other topics, publics around the world are more divided. Americans (67%) and Canadians (52%) express some of the highest support for being able to say things in public that are offensive to minorities, as do those in a few countries in Latin America and Europe. At least half in the Philippines, Australia, Tanzania and South Africa also say people should be able to say these types of things publicly. In most of the other countries surveyed, however, majorities say the government should be able to prevent speech that is offensive to minority groups.

A similar pattern emerges on the issue of religion. Roughly six-in-ten or more in the U.S. (77%), Canada (64%), Australia (62%), and the Philippines (59%) support allowing speech that is offensive to their own religious beliefs. Europeans and Latin Americans are divided, while most people in the Middle East, Africa and other Asian nations support the government restricting this type of speech.

Few people around the world believe that people should be able to say things that are sexually explicit, such as sexually graphic jokes, in public. Majorities in most countries think the government should be able to restrict this type of speech. The few countries where at least half support being able to say these things in public are Spain (70%), the U.S. (52%) and Poland (50%).

Broad majorities in nearly every country surveyed also think the government should be able to prevent people from calling for violent protests in public. Opposition to this type of speech is particularly widespread in Lebanon (94%), Senegal (89%) and Germany (88%). Filipinos, South Africans and Americans are somewhat more divided, while only in Poland does a majority (60%) say this type of speech should be allowed in public.

Free Press Supported except on Matters of National Security

Free Press Supported except on Matters of National Security

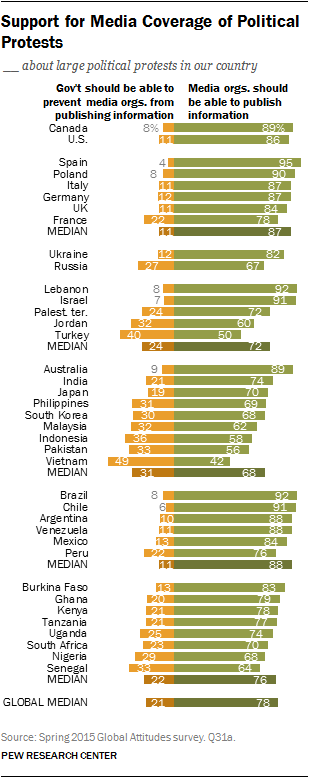

At least three-quarters in each country surveyed in Europe and Latin America, as well as in the U.S. and Canada, say the media should be able to publish information about protests in the country without government interference. Similarly, 82% in Ukraine support this type of free press. Two-thirds in Russia agree.

There is also widespread support in Africa for the media publishing information about protests. More than six-in-ten in each country surveyed approve of this type of free press, including more than three-quarters in Burkina Faso (83%), Ghana (79%), Kenya (78%) and Tanzania (77%).

Opinion on this aspect of a free press is more divided in the Middle East and Asia-Pacific regions. Overall, a median of 72% in the Middle Eastern countries surveyed say the press should be able to publish information about protests in the country. Lebanese (92%) and Israelis (91%) are particularly supportive, but Turks are more divided (50% say press should be able to publish, 40% say government should restrict).

In the Asia-Pacific region, Australians (89%) express the highest level of support for the press publishing information about protests, while much smaller majorities in Indonesia (58%) and Pakistan (56%) agree. The Vietnamese are divided on the issue (42% press publish, 49% government restrict).

In the Asia-Pacific region, Australians (89%) express the highest level of support for the press publishing information about protests, while much smaller majorities in Indonesia (58%) and Pakistan (56%) agree. The Vietnamese are divided on the issue (42% press publish, 49% government restrict).

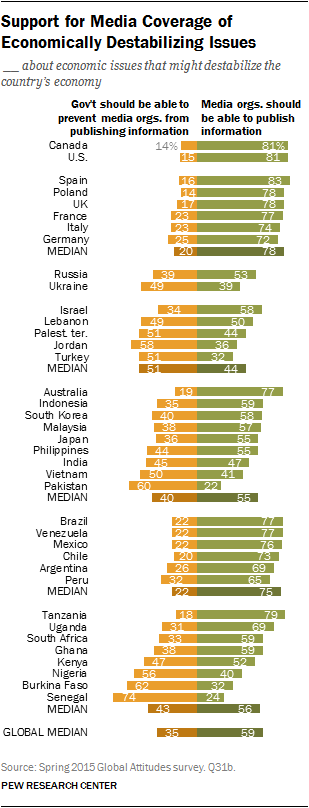

When it comes to reporting on economic issues that might destabilize the country’s economy, support for a free press continues to be highest in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Latin America.

Support is lower in Africa and in the Asia-Pacific region. While majorities in many of the countries say the press should be able to publish information that might harm the economy, significant percentages also believe that the government should be able to restrict this type of press. This includes half or more in Senegal, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Pakistan and Vietnam.

In the Middle East, Israel is the only country where a majority of the public says the press should be able to report on economic issues that might be destabilizing. In the other four countries surveyed, roughly half or more say the government should be able to regulate this type of reporting, including nearly six-in-ten in Jordan (58%).

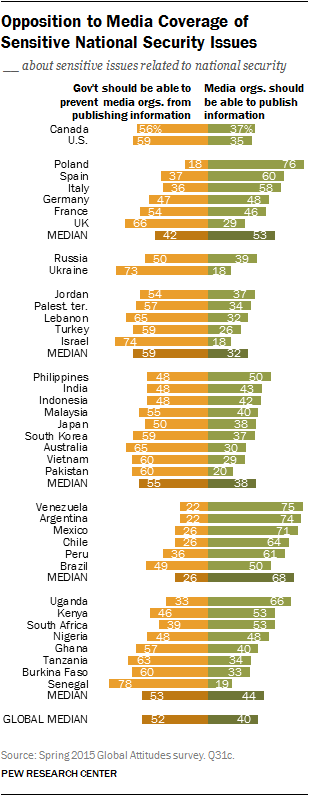

Roughly half or more in 27 of the 38 countries surveyed say the government should be able to prevent the media from publishing information about sensitive issues related to national security. This includes majorities in many of the publics that expressed widespread support for free speech and a free press on other topics, such as the UK (66% say government should be able to restrict), the U.S. (59%), Canada (56%) and France (54%).

Roughly half or more in 27 of the 38 countries surveyed say the government should be able to prevent the media from publishing information about sensitive issues related to national security. This includes majorities in many of the publics that expressed widespread support for free speech and a free press on other topics, such as the UK (66% say government should be able to restrict), the U.S. (59%), Canada (56%) and France (54%).

Latin American countries, on the other hand, continue to support this type of free press. At least six-in-ten in Venezuela, Argentina, Mexico, Chile and Peru say the media should be able to publish on sensitive national security issues. The few other countries where clear majorities agree are Poland (76%), Uganda (66%), Spain (60%) and Italy (58%).

Divides over Free Speech and Free Press

In general, people who say it is very important to have free speech and a free press in their country are also more supportive than others of allowing speech across various controversial topics. For example, in the U.S., 60% of those who prioritize free speech think that right should extend to people’s freedom to say sexually explicit things in public. Among those for whom free speech is less of a priority, just 31% agree. Similarly, in Italy, 66% of people who say a free press is very important believe that the media should be able to publish sensitive issues related to national security. By comparison, 45% of Italians who do not prioritize a free press as intensely say the same.

In general, people who say it is very important to have free speech and a free press in their country are also more supportive than others of allowing speech across various controversial topics. For example, in the U.S., 60% of those who prioritize free speech think that right should extend to people’s freedom to say sexually explicit things in public. Among those for whom free speech is less of a priority, just 31% agree. Similarly, in Italy, 66% of people who say a free press is very important believe that the media should be able to publish sensitive issues related to national security. By comparison, 45% of Italians who do not prioritize a free press as intensely say the same.

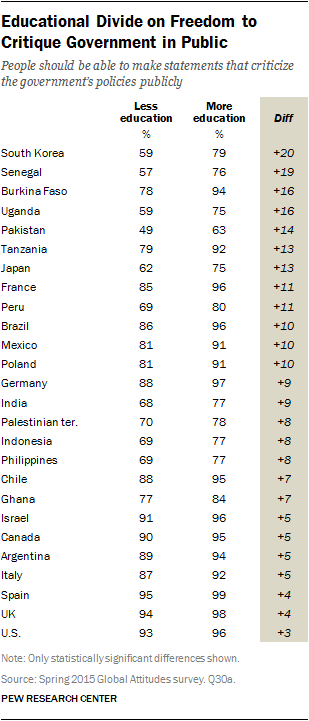

There are also some notable demographic differences on these issues. In many countries, people with a higher level of education are more likely than those with less education to support being able to criticize government policies in public. A similar educational divide is found over allowing the media to cover large political protests in the country.

People who are religiously devout are less supportive of being able to say things that are offensive to religious groups or that are sexually explicit, especially in Europe, the U.S. and Canada. For example, 46% of Americans who pray daily think people should be able to make statements in public that are sexually explicit, while 58% of Americans who pray less often say the same. In France, 43% of people who say religion is very important in their lives believe people should be able to say things that are offensive to religious groups in public. A majority (55%) of those for whom religion is less important agree.

People who are religiously devout are less supportive of being able to say things that are offensive to religious groups or that are sexually explicit, especially in Europe, the U.S. and Canada. For example, 46% of Americans who pray daily think people should be able to make statements in public that are sexually explicit, while 58% of Americans who pray less often say the same. In France, 43% of people who say religion is very important in their lives believe people should be able to say things that are offensive to religious groups in public. A majority (55%) of those for whom religion is less important agree.

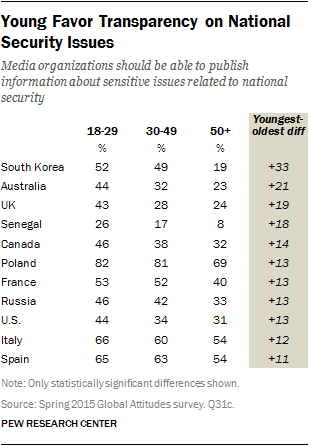

In 16 of the 38 countries surveyed, people ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those ages 50 and older to say that people should be able to make sexually explicit statements in public. And young people in Europe, Canada, the U.S., Australia, South Korea, Russia and Senegal are more supportive than their elders of the press being able to publish sensitive information about national security issues.

Finally, there is evidence that in some countries people who are part of a minority group are less supportive of being able to say things that are offensive to minority groups in general. For example, in the U.S., non-whites (57%), including Hispanics, are much less likely to agree that people should be able to say these types of statements in public than are whites (72%). Similarly, Arabs in Israel (15%) are less supportive of this form of speech than Jews (39%).