In recent years, Russia’s relationship with Western countries, specifically with members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), has been on a roller-coaster ride. In 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed a New START agreement that reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads on each side by roughly 30%. But Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its ongoing support for separatist forces in eastern Ukraine has once more strained relations between Russia and Western nations.

Going forward, most NATO members are willing to provide economic aid to Ukraine and offer it NATO membership. But they generally shy away from sending arms to Kyiv or escalating economic sanctions against Moscow. And at least half in Germany, France and Italy are unwilling to use military force to defend other NATO allies against Russian aggression.

Russia, Putin in Disfavor

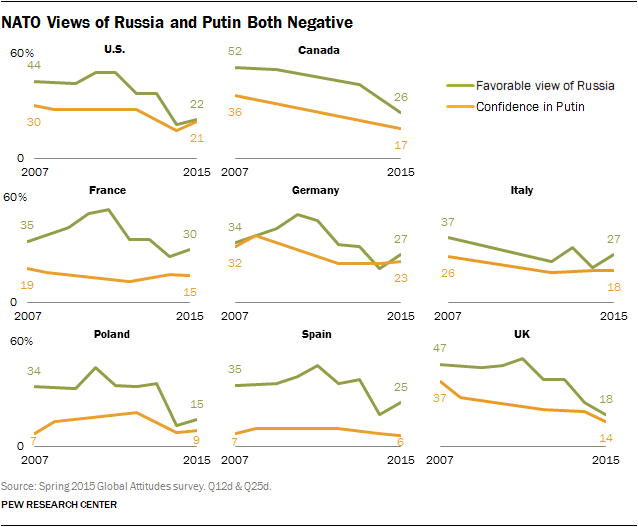

Both Russia and its current president, Vladimir Putin, are held in low regard in the eight NATO countries surveyed. Public attitudes toward both Russia and its leader have been in steady decline over the past few years, though in the past 12 months views of Russia have rebounded slightly in Germany, Italy and Spain. Nevertheless, the median favorability of Russia is down to 26% from 37% in 2013. And the median confidence in Putin to do the right thing regarding world affairs is down to 16% from 28% in 2007.

Russia’s current image problems are especially bad in Poland. Poland has had a long, painful relationship with Russia, having been invaded, dismembered and occupied by a series of Russian and Soviet regimes. Thus it is hardly surprising that just 15% of Poles have a favorable view of Russia. But the Poles have not always despaired of their ties with their neighbor. As recently as 2010, 45% of Poles had a favorable view of Russia – three times the current share. Just as striking, in 2010 only 11% had a very unfavorable opinion of Russia. Now more than three times that number, 40%, intensely dislike Russia.

The British have similarly turned against Russia. Only 18% in the United Kingdom voice a favorable view of the country. This is down from 25% of the British in 2014 and 50% in 2011. It is also notable that in 2011 only 7% of the British said they held very unfavorable views of Russia. In 2015, that proportion has quadrupled to 28%.

Only 22% of Americans express a favorable opinion of Russia. This is largely unchanged from last year, but down from 49% in both 2010 and 2011. At the same time, however, intense animosity toward Russia seems to be waning in the past year. The proportion of Americans holding very unfavorable views is down 11 percentage points, from 38% in 2014 to 27% in 2015. Still, older Americans are more than three times as likely as younger Americans (40% vs. 11%) to see Russia in a negative light.

Fewer than three-in-ten Germans (27%) hold a favorable view of Russia. This assessment has improved 8 points since last year. But it is down from a recent high of 50% in 2010. German men are twice as likely as women to have a positive opinion of Russia.

Views of Putin in NATO countries have historically been very low and have dropped even further in some countries in recent years. Putin’s peak popularity was in 2003, a heady time when 75% of Germans (rivaling the 76% of Russians with faith in Putin), 54% of Canadians, 53% of British, 48% of French, 44% of Italians and 41% of Americans had confidence in him to do the right thing regarding world affairs.

Putin has never again attained this level of trust in the West. Today, fewer than a quarter voice confidence in his leadership in any country, including just 9% in Poland and 6% in Spain. These attitudes are largely unchanged from 2014. It is older and more highly educated people in both the UK and the U.S. who are most likely to voice no confidence in Putin.

Russia Seen as Threat to Neighbors

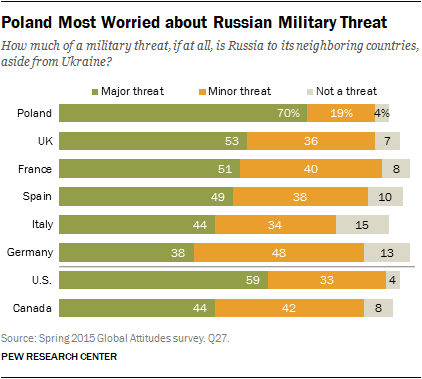

There is widespread public concern in some NATO member states that Russia poses a military threat to neighboring countries aside from Ukraine. Seven-in-ten Poles say Moscow poses a major danger, as do roughly six-in-ten Americans (59%) and about half of British (53%) and French (51%). But only 44% of Italians and 38% of Germans see Russia as a major menace. Notably, while older Americans (64%) are far more likely than younger ones (51%) to say Moscow is a military danger, it is younger French (63%) rather than their elders (47%) who are the most worried.

There is widespread public concern in some NATO member states that Russia poses a military threat to neighboring countries aside from Ukraine. Seven-in-ten Poles say Moscow poses a major danger, as do roughly six-in-ten Americans (59%) and about half of British (53%) and French (51%). But only 44% of Italians and 38% of Germans see Russia as a major menace. Notably, while older Americans (64%) are far more likely than younger ones (51%) to say Moscow is a military danger, it is younger French (63%) rather than their elders (47%) who are the most worried.

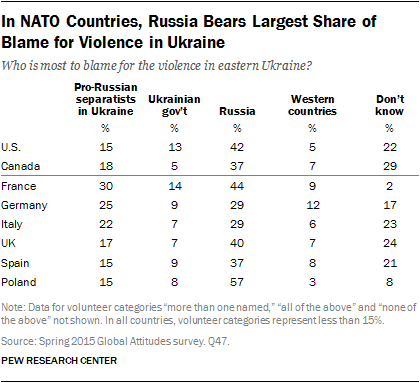

When it comes to the current conflict in eastern Ukraine, NATO members tend to see Russia as responsible for the fighting. A majority of Poles (57%) say Moscow is behind the violence in Ukraine, as do four-in-ten or more French (44%), Americans (42%) and British (40%). But only roughly three-in-ten Germans and Italians (both 29%) agree. Older Americans (50%) and Brits (45%) are more likely than their younger compatriots (33% of both Americans and British) to blame Russia. And in all but Germany, those who blame Russia for the violence in eastern Ukraine are the most likely to see Russia as a military threat.

When it comes to the current conflict in eastern Ukraine, NATO members tend to see Russia as responsible for the fighting. A majority of Poles (57%) say Moscow is behind the violence in Ukraine, as do four-in-ten or more French (44%), Americans (42%) and British (40%). But only roughly three-in-ten Germans and Italians (both 29%) agree. Older Americans (50%) and Brits (45%) are more likely than their younger compatriots (33% of both Americans and British) to blame Russia. And in all but Germany, those who blame Russia for the violence in eastern Ukraine are the most likely to see Russia as a military threat.

Other actors in the Ukraine drama are seen as less culpable for the hostilities in eastern Ukraine. Three-in-ten French, 25% of Germans and 22% of Italians say pro-Russian Ukrainian separatists are responsible for the violence there. Few say the responsibility lies with the Ukrainian government itself. And only in Germany (12%) does a double-digit minority believe that the actions of Western governments in Europe and the U.S. are accountable for the hostilities.

Views of NATO Generally Favorable

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization is the Western alliance created in 1949 to provide collective security for its members in the face of the military threat then posed by the Soviet Union. NATO now includes 28 countries from Europe and North America. The eight NATO members surveyed by Pew Research Center in 2015 account for 78% of NATO countries’ population, 88% of their gross domestic product and 94% of their defense spending.

Overall, NATO members have a favorable view of their 66-year-old alliance. A median of 62% expresses a positive perception of the organization. But this generally upbeat attitude masks national differences that highlight current tensions and possible future difficulties for the coalition. It also does not capture differences within countries. For example, people who place themselves on the right of the ideological spectrum are more supportive than those on the left in Spain, France and Germany. But only in Spain do more than half of people on the left have an unfavorable attitude toward NATO. In the U.S., a majority of Democrats (56%) voice a favorable opinion of the organization, but only about four-in-ten Republicans (43%) share that view.

Overall, NATO members have a favorable view of their 66-year-old alliance. A median of 62% expresses a positive perception of the organization. But this generally upbeat attitude masks national differences that highlight current tensions and possible future difficulties for the coalition. It also does not capture differences within countries. For example, people who place themselves on the right of the ideological spectrum are more supportive than those on the left in Spain, France and Germany. But only in Spain do more than half of people on the left have an unfavorable attitude toward NATO. In the U.S., a majority of Democrats (56%) voice a favorable opinion of the organization, but only about four-in-ten Republicans (43%) share that view.

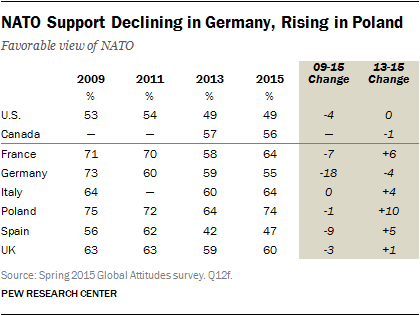

Given their contentious history with Russia and their proximity to the fighting in Ukraine, it is not surprising that 74% of Poles hold a favorable opinion of NATO and the security reassurance membership in it provides. Polish support for the alliance is up 10 percentage points from 2013. Six-in-ten or more French (64%), Italians (64%) and British (60%) also hold a favorable view of NATO. However, roughly a third of the French (34%) and about a quarter of Italians (26%) express an unfavorable attitude toward NATO.

The greatest change in support for NATO has been in Germany, where favorability of the alliance has fallen 18 points since 2009, from 73% to 55%. Germans living in the east are divided – 46% see it positively, 43% negatively.

The American public’s attitude toward NATO belies the U.S. role in the organization. U.S. defense expenditures account for 73 percent of the defense spending of the alliance as a whole. And this is among the highest proportion of total alliance security spending since the early 1950s. But only 49% of Americans express a favorable opinion of the security organization. This is unchanged from 2013 but down from 54% in 2010 and 2011. Meanwhile, the proportion of Americans who say they have an unfavorable view of NATO has grown from 21% in 2010 to 31% in 2015.

What to Do about Ukraine

In response to the situation involving Russia and Ukraine, publics in NATO member countries were given options as to what, if anything, they wanted to do about it. The survey suggests they support economic aid for beleaguered Ukraine, but comparatively few favor doing much else.

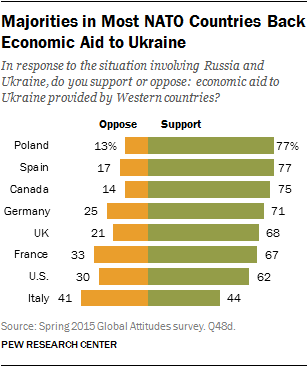

The greatest support for helping Ukraine is for the most passive option: economic aid. A median of 70% backs providing the government in Kyiv with financial assistance in response to the situation involving Russia. The strongest proponents of such aid are Poles (77%), Spanish (77%), Canadians (75%) and Germans (71%). The most reluctant to provide financial assistance are the Italians, with 44% favoring it and 41% in opposition. It is older Spanish (81%) and Americans (68%) who back aid more than their younger compatriots (66% of Spanish and 53% of Americans). People on the left are more supportive than those on the right in France, Italy and the UK.

The greatest support for helping Ukraine is for the most passive option: economic aid. A median of 70% backs providing the government in Kyiv with financial assistance in response to the situation involving Russia. The strongest proponents of such aid are Poles (77%), Spanish (77%), Canadians (75%) and Germans (71%). The most reluctant to provide financial assistance are the Italians, with 44% favoring it and 41% in opposition. It is older Spanish (81%) and Americans (68%) who back aid more than their younger compatriots (66% of Spanish and 53% of Americans). People on the left are more supportive than those on the right in France, Italy and the UK.

Ukraine’s relationship with NATO has long been the topic of contentious debate, both within the country and among the members of the Western security pact. Since the end of the Cold War, governments in Kyiv have wavered between a desire to eventually join the alliance and a desire to remain nonaligned.

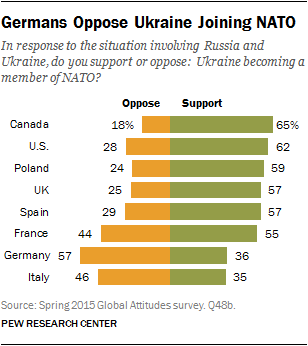

A median of 57% of the NATO publics surveyed support offering Ukraine NATO membership in response to the situation involving Russia. About two-thirds of Canadians (65%) favor that option, as do roughly six-in-ten Americans (62%) and Poles (59%). Germans (36%) and Italians (35%) are the least supportive of Ukraine’s membership in NATO. In fact, a majority of Germans (57%) and a plurality of Italians (46%) oppose offering Kyiv this option.

A median of 57% of the NATO publics surveyed support offering Ukraine NATO membership in response to the situation involving Russia. About two-thirds of Canadians (65%) favor that option, as do roughly six-in-ten Americans (62%) and Poles (59%). Germans (36%) and Italians (35%) are the least supportive of Ukraine’s membership in NATO. In fact, a majority of Germans (57%) and a plurality of Italians (46%) oppose offering Kyiv this option.

NATO membership for Ukraine is backed more by older (66%) than younger Americans (55%). Conversely, younger Germans (51%), French and Poles (both 64%) favor it more than their elders (32% of Germans, 52% of French and 54% of Poles).

Notably, despite recent developments, support for Ukrainian membership in NATO is relatively unchanged in a number of alliance countries – France, Germany, Italy, Poland – compared with attitudes expressed in 2009, when Pew Research Center asked publics a standalone question: if they favored Ukraine joining NATO in the next decade. Among the nations surveyed, support for Ukrainian membership in the defense alliance has increased by double digits in the U.S., the UK and Spain.

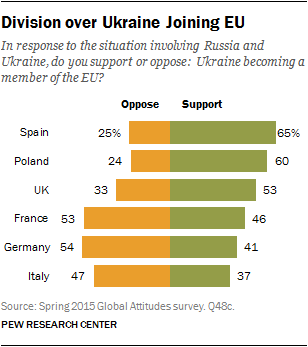

The prospect of Ukraine one day joining the European Union (EU) is at the heart of much recent Ukraine-Russia tension and helped spark the Euromaidan demonstrations in Ukraine that eventually led to the ouster of Viktor Yanukovych and his government in February 2014. The six EU member nations surveyed are divided over offering Ukraine membership in the EU in response to the situation involving Russia and Ukraine. The strongest support comes from the Spanish (65%) and Poles (60%). Italians (37%) are the least willing to offer Ukraine a spot at the EU table. And more than half of Germans (54%) and French (53%) are openly opposed to membership. Notably, a majority of older Germans (57%) are against Ukraine joining the EU, compared with 42% of younger Germans. People on the left are more supportive of EU membership for Ukraine than people on the right in Italy, the UK, France and Spain.

The prospect of Ukraine one day joining the European Union (EU) is at the heart of much recent Ukraine-Russia tension and helped spark the Euromaidan demonstrations in Ukraine that eventually led to the ouster of Viktor Yanukovych and his government in February 2014. The six EU member nations surveyed are divided over offering Ukraine membership in the EU in response to the situation involving Russia and Ukraine. The strongest support comes from the Spanish (65%) and Poles (60%). Italians (37%) are the least willing to offer Ukraine a spot at the EU table. And more than half of Germans (54%) and French (53%) are openly opposed to membership. Notably, a majority of older Germans (57%) are against Ukraine joining the EU, compared with 42% of younger Germans. People on the left are more supportive of EU membership for Ukraine than people on the right in Italy, the UK, France and Spain.

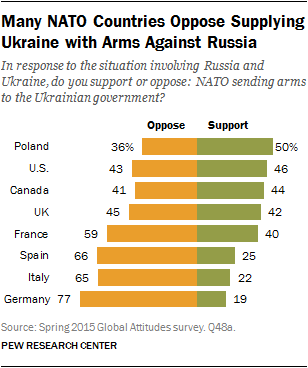

There is relatively little support among NATO members for sending arms to the Ukrainian government. A median of only 41% back such action. Despite Poles’ general antipathy toward Russia, their concern about the military threat posed by Russia and their blaming Moscow for the current violence in Ukraine, only half (50%) want NATO to give arms to Kyiv. Americans are divided on the issue: 46% support sending weaponry, 43% oppose it. A majority of older Americans (56%) favor arming the Ukrainians, while more than half of younger Americans (54%) oppose it. And majorities in four of the eight nations are against helping arm the Ukrainians. The strongest opposition is in Germany (77%), Spain (66%) and Italy (65%).

There is relatively little support among NATO members for sending arms to the Ukrainian government. A median of only 41% back such action. Despite Poles’ general antipathy toward Russia, their concern about the military threat posed by Russia and their blaming Moscow for the current violence in Ukraine, only half (50%) want NATO to give arms to Kyiv. Americans are divided on the issue: 46% support sending weaponry, 43% oppose it. A majority of older Americans (56%) favor arming the Ukrainians, while more than half of younger Americans (54%) oppose it. And majorities in four of the eight nations are against helping arm the Ukrainians. The strongest opposition is in Germany (77%), Spain (66%) and Italy (65%).

In a related question concerning the situation involving Russia and Ukraine, Americans, Canadians and publics in the six EU member states in the survey were asked if they thought that the economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the EU and the U.S. should be increased, decreased or kept about the same as they are now. Outside of Poland, there is little appetite for escalating financial penalties. About half of Poles (49%) back ratcheting up economic sanctions. Roughly three-in-ten Italians (30%), Canadians (28%) and Americans (28%) agree. But only about a quarter of the French (25%) and the Spanish (24%) go along. Only one-in-five Germans want more economic pressure applied to Moscow. There is also relatively little interest in decreasing sanctions, except in Germany (29%). Most publics – including 53% of both Americans and British – want to keep the penalties about where they are now.

Mixed Views on Coming to the Aid of NATO Allies

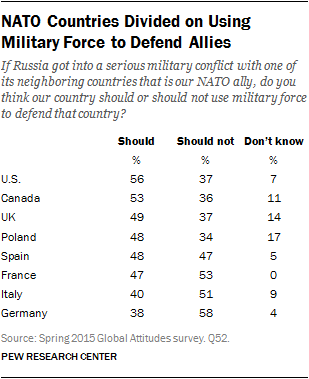

In Article 5 of the 1949 North Atlantic Treaty that created NATO, member states “agree that an armed attack against one or more of them … shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that [they] will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by … such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force.” This commitment to collective self-defense has been the backbone of NATO since its founding, a tripwire to deter Soviet aggression throughout the Cold War. But in the face of Russian activities in Ukraine, not all NATO-member publics are willing to live up to their Article 5 obligation.

Roughly half or fewer in six of the eight countries surveyed say their country should use military force if Russia attacks a neighboring country that is a NATO ally. And at least half in three of the eight NATO countries say that their government should not use military force in such circumstances. The strongest opposition to responding with armed force is in Germany (58%), followed by France (53%) and Italy (51%). Germans (65%) and French (59%) ages 50 and older are more opposed to the use of military force against Russia than are their younger counterparts ages 18 to 29 (Germans 50%, French 48%). German, British and Spanish women are particularly against a military response.

Roughly half or fewer in six of the eight countries surveyed say their country should use military force if Russia attacks a neighboring country that is a NATO ally. And at least half in three of the eight NATO countries say that their government should not use military force in such circumstances. The strongest opposition to responding with armed force is in Germany (58%), followed by France (53%) and Italy (51%). Germans (65%) and French (59%) ages 50 and older are more opposed to the use of military force against Russia than are their younger counterparts ages 18 to 29 (Germans 50%, French 48%). German, British and Spanish women are particularly against a military response.

More than half of Americans (56%) and Canadians (53%) are willing to respond to Russian military aggression against a fellow NATO country. A plurality of the British (49%) and Poles (48%) would also live up to their Article 5 commitment. And the Spanish are divided on the issue: 48% support it, 47% oppose.

While some in NATO are reluctant to help aid others attacked by Russia, a median of 68% of the NATO member countries surveyed believe that the U.S. would use military force to defend an ally. The Canadians (72%), Spanish (70%), Germans (68%) and Italians (68%) are the most confident that the U.S. would send military aid. In many countries, young Europeans express the strongest faith in the U.S. to help defend allied countries. The Poles, citizens of the most front-line nation in the survey, have their doubts: 49% think Washington would fulfill its Article 5 obligation, 31% don’t think it would and 20% aren’t sure.

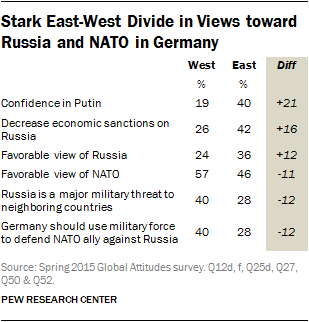

Germany: Old Divisions over Russia and NATO Remain

There is also internal German disagreement on what to do about Ukraine and Russia. German reunification has not closed the east-west divide in that country, a division that has its origins in the Cold War.

There is also internal German disagreement on what to do about Ukraine and Russia. German reunification has not closed the east-west divide in that country, a division that has its origins in the Cold War.

Overall, Germans see neither Russia nor Putin in a positive light. But eastern Germans (40%) are twice as likely as western Germans (19%) to have confidence in Putin. And more than a third of those in the east (36%) have a favorable opinion of Russia compared with just 24% of western Germans. Easterners (28%) are also less likely than westerners (40%) to believe that Russia poses a military threat to its neighbors. And they are more likely to want to ease economic sanctions on Russia.

Conversely, people living in western Germany (57%) are more supportive of NATO than are those in the east (46%). And they are more likely than their eastern compatriots to support the use of military force to defend other NATO allies.

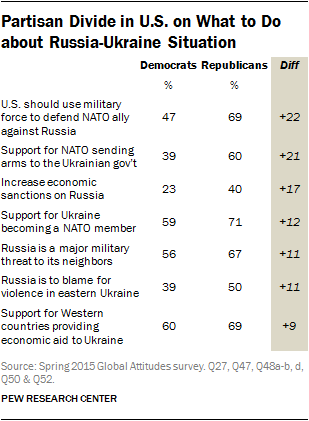

Major Partisan Split in the U.S.

Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. are strongly divided on the situation in Ukraine and what to do about it. Members of both parties see Russia as a major military threat to neighboring countries, but to a different degree. Two-thirds of the GOP sees Russia in that light, but only 56% of Democrats share their fear. And while half of Republicans say Russia is to blame for the violence in eastern Ukraine, just 39% of Democrats agree.

There is a similar partisan divide over what to do about the situation in Ukraine. The smallest division is over economic aid to Kyiv: 69% of Republicans back such assistance, as do 60% of Democrats. But while 60% of Republicans would send arms to the Ukrainians, only 39% of Democrats agree.

There is a similar partisan divide over what to do about the situation in Ukraine. The smallest division is over economic aid to Kyiv: 69% of Republicans back such assistance, as do 60% of Democrats. But while 60% of Republicans would send arms to the Ukrainians, only 39% of Democrats agree.

With regard to U.S. and EU economic sanctions on Russia, substantial percentages of both parties favor keeping them about the same (44% of GOP and 54% of Democrats). However, 40% of Republicans would increase those sanctions, but only 23% of Democrats approve of such action.

Members of both parties support NATO membership for Ukraine. Such support is greater among the GOP (71%) than among Democrats (59%). Moreover, there is a partisan difference about U.S. obligations to come to the military assistance of other NATO members. Nearly seven-in-ten Republicans (69%) say that Washington should come to the aid of its allies in the event of Russian aggression. But only 47% of Democrats back that long-standing U.S. treaty obligation, while 48% oppose it.