Trade and foreign investment engender both faith and skepticism around the world, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of 44 nations.

Trade and foreign investment engender both faith and skepticism around the world, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of 44 nations.

Global publics generally agree that international commercial activity is a good thing, particularly people in developing and emerging economies.

But not everyone is convinced, especially in advanced economies. Such skepticism is particularly strong in France, Italy, Japan and the United States. Each of these nations is involved in negotiating major regional trade agreements. That undercurrent of skepticism could complicate current government efforts to further deepen and broaden global markets.

Publics across a diverse range of advanced, emerging and developing economies overwhelmingly say that international trade and global business ties are good for their country.1 A global median of 81% among the nations surveyed hold such views. People also generally voice the opinion (a median of 74%) that it is beneficial for their economy when foreign companies build new factories in their country.

But publics embrace such economic globalization with notable reservations. A median of only 31% say trade is very good for their economy. Just over half (54%) believe trade creates jobs. Only a plurality (45%) holds the view that it increases wages. And barely a quarter (26%) share the opinion that trade lowers prices, suggesting that many people do not accept one of economists’ principal arguments for why nations should trade.

Developing countries provide the strongest support across the board for foreign investment, trade and the benefits to be derived from globalization. A median of 87% of those surveyed in the developing world say trade is good for the economy, including 47% who say it is very good. Fully 85% see foreign companies building plants in their country as beneficial. In addition, 66% say growing international business ties create jobs and 57% say foreign companies buying domestic companies is good. And 55% voice the view that trade increases wages.

Developing countries provide the strongest support across the board for foreign investment, trade and the benefits to be derived from globalization. A median of 87% of those surveyed in the developing world say trade is good for the economy, including 47% who say it is very good. Fully 85% see foreign companies building plants in their country as beneficial. In addition, 66% say growing international business ties create jobs and 57% say foreign companies buying domestic companies is good. And 55% voice the view that trade increases wages.

A median of 78% in emerging markets see trade as beneficial, including 25% who say it is very good. And 52% say trade creates jobs, while a plurality believes it leads to higher wages (45%). Such emerging market sentiment may reflect the experience in China and elsewhere, where growing international business ties have been associated with more employment opportunities and higher incomes.

However, overall support for trade in emerging markets has waned slightly in recent years. Among the 13 emerging market countries surveyed in both 2010 and 2014, the median view that international trade and business ties are good has dipped from 84% four years ago to 77% today. This may, in part, be due to the fact that the annual rate of export growth by the emerging markets surveyed slowed from an average of 14% in 2010 to 3% in 2013, according to the World Bank.

While 84% in advanced economies say trade is good for their country, there is less enthusiasm. Only 44% voice the view that trade boosts employment and just 25% say it leads to higher wages. Such opinions are likely the casualty of the convergence of globalization with slow economic growth, high unemployment and stagnating incomes in these nations.

Views of the impact of trade on prices are among the most striking findings from this new survey. Most economists contend that trade lowers prices for consumers. But half of those in developing countries (a median of 50%) and a plurality (42%) in emerging markets say trade actually increases the prices of products sold. Publics in advanced economies are divided on the topic.

These are the results of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 48,643 respondents from March 17 to June 5, 2014.

The Champions of Trade

The benefits of trade are strongly appreciated in developing and emerging markets.

The benefits of trade are strongly appreciated in developing and emerging markets.

Among all countries surveyed, Tunisians (87%), Ugandans (82%) and Vietnamese (78%) are the most likely to say trade creates new employment. Just 5% of Tunisians and Vietnamese fear that trade destroys jobs.

Ugandans (79%), Bangladeshis (78%) and Lebanese (77%) have the greatest faith that trade leads to higher wages. Only 12% of Ugandans, 14% of Bangladeshis and 7% of Lebanese voice the view that growing international business ties undermine domestic incomes.

Roughly six-in-ten Chinese (61%) also see growing international business ties as a way to improve local incomes. Such sentiment may be rooted in China’s recent experience. Wages have grown by an average of more than 10% annually for more than a decade at a time when the country’s merchandise exports were rising an average of 15% per year.

Roughly six-in-ten Chinese (61%) also see growing international business ties as a way to improve local incomes. Such sentiment may be rooted in China’s recent experience. Wages have grown by an average of more than 10% annually for more than a decade at a time when the country’s merchandise exports were rising an average of 15% per year.

People in emerging and developing countries such as Bangladesh (69%), Tanzania (68%), the Philippines (66%) and Kenya (66%) are also the most open to foreigners buying their local companies. Roughly a third or less in those nations see such foreign investment as a bad thing.

The Trade Doubters

Some of the greatest public skepticism about trade and foreign investment is found in the United States. In 2002, 78% of Americans held the view that growing trade and business ties with other countries was a good thing. This sentiment was roughly comparable to that voiced at the time in the other 14 nations surveyed every year between 2002 and 2014.

Some of the greatest public skepticism about trade and foreign investment is found in the United States. In 2002, 78% of Americans held the view that growing trade and business ties with other countries was a good thing. This sentiment was roughly comparable to that voiced at the time in the other 14 nations surveyed every year between 2002 and 2014.

But then Americans’ mood began to change. By 2007, before the Great Recession hit, the U.S. public’s belief in the benefit of growing international business ties had fallen 19 percentage points to 59% and would tumble further to 53%, in 2008. Faith in the value of trade remained fairly steady worldwide during this time period. By 2010, global belief in the efficacy of trade was at 84%, while the U.S. number recovered to only 66%. Since then, the global median has slid to 76%, pulled down by eroding confidence in trade in some emerging markets, while views in the U.S. have remained relatively stable at 68% in 2014.

This discontinuity between American views of globalization and the sentiments of most people around the world is also evident in public perspectives on the impact of trade. In developing economies, a median of 66% say trade increases jobs and 55% say it grows wages. In emerging markets, 52% say global business ties create jobs and 45% hold the view that it improves wages. Americans, on the other hand, are among the least likely to say trade creates jobs (20%) or improves wages (17%), exhibiting notably less faith in the benefits of trade than others in advanced economies.

This discontinuity between American views of globalization and the sentiments of most people around the world is also evident in public perspectives on the impact of trade. In developing economies, a median of 66% say trade increases jobs and 55% say it grows wages. In emerging markets, 52% say global business ties create jobs and 45% hold the view that it improves wages. Americans, on the other hand, are among the least likely to say trade creates jobs (20%) or improves wages (17%), exhibiting notably less faith in the benefits of trade than others in advanced economies.

There is a similar divergence in views about different forms of foreign direct investment. Americans share the perspective of most publics around the world that greenfield investment –foreigners building plants in the respondent’s country –is a good thing. But only 28% of Americans say foreign-led mergers and acquisitions (M&A) of domestic firms are beneficial to the economy. This compares with 57% in developing markets and 44% in emerging nations.

But Americans are not alone in voicing doubts about trade and foreign investment. Publics in a number of other advanced economies – in particular France, Italy and Japan – stand out for their skepticism. These nations matter because the four account for nearly a quarter (24%) of world merchandise imports and around a fifth (21%) of world services imports. Protectionist sentiments in any of these societies, if acted upon, can reverberate around the world.

But Americans are not alone in voicing doubts about trade and foreign investment. Publics in a number of other advanced economies – in particular France, Italy and Japan – stand out for their skepticism. These nations matter because the four account for nearly a quarter (24%) of world merchandise imports and around a fifth (21%) of world services imports. Protectionist sentiments in any of these societies, if acted upon, can reverberate around the world.

A global median, excluding those four countries, of just 19% hold the view that trade destroys jobs. But 59% of Italians, 50% of Americans, 49% of French and 38% of Japanese see trade as destructive of employment. Just 21% of the global public in the survey hold the view that trade lowers wages. But 52% of Italians, 47% of the French, 45% of Americans and 37% of Japanese say trade undermines domestic incomes. And 46% of the world public voices the view that foreign companies buying domestic firms is bad for their country. Fully 76% of Japanese, 73% of Italians, 68% of French and 67% of Americans judge foreign-led M&A harshly.

Notably, the French and Americans manifest some of the only demographic differences on trade and investment-related concerns. Women more than men express the opinion that trade hurts employment in the U.S. (55% to 46%) and in France (54% to 45%). In both countries, older people, those ages 50 and above, are less enthusiastic about trade in general than younger people, those ages 18 to 29. Older people in the U.S. and France are also more likely than younger people to say trade destroys jobs. Similarly, lower income Americans and French are more fearful trade will decrease employment than are their fellow countrymen with upper incomes.

Implications for Major Trade Deals

The U.S., Japan and France are the first, third and fifth largest economies in the world. Japan and the United States are the two principal protagonists in efforts to negotiate the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) among a dozen countries from Asia, North America and South America that border on the Pacific Ocean. France and the United States are negotiating the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) along with 27 other European Union members. Governments’ objective in doing these deals is to spur economic growth and job creation and to boost incomes.

The U.S., Japan and France are the first, third and fifth largest economies in the world. Japan and the United States are the two principal protagonists in efforts to negotiate the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) among a dozen countries from Asia, North America and South America that border on the Pacific Ocean. France and the United States are negotiating the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) along with 27 other European Union members. Governments’ objective in doing these deals is to spur economic growth and job creation and to boost incomes.

American, French, Italian and Japanese views are out of step with those of their TPP and TTIP counterparts on a number of trade and investment issues. Americans and Japanese are far less likely than publics in other TPP countries (a median of 55%) to hold the view that growing international business ties will create new employment, a politically sensitive issue in each country. And French (24%), Americans (20%) and Italians (13%) are less likely than their TTIP negotiating partners (a median of 50%) to agree that trade leads to more jobs. Americans, French, Italians and Japanese are also more skeptical than others in the two sets of trade talks about the impact of trade on wages and the value of foreigners buying local companies.

1. Trade Broadly Viewed as Beneficial

There is a widely shared public consensus around the world that growing trade and business ties between one’s own country and other nations are a good thing. This view is held by men and women, by rich and poor, by young and old, by those who are well educated and by less educated people and by people across the political spectrum. A majority in each of the 44 countries surveyed — in most cases an overwhelming majority — voice the view that such globalization is good for their nation.

Among those African economies surveyed, a median of 87% say trade is good, including 47% who voice the view that it is very good for their country. The African countries most enamored of trade are Uganda (70% very good), Tanzania (54%) and Nigeria (53%).

Among those African economies surveyed, a median of 87% say trade is good, including 47% who voice the view that it is very good for their country. The African countries most enamored of trade are Uganda (70% very good), Tanzania (54%) and Nigeria (53%).

In Asia, a median of 86% express the opinion that such business ties are beneficial, including 24% who say it is very good. The Vietnamese (53% very good) are particularly taken by trade.

In Latin America, 80% see trade as a good thing. In the region, Nicaraguans (64% very good) are the most enthusiastic about the benefit of international commerce. In the Middle East, 77% view trade as good, including Tunisians (77% very good) and Lebanese (50%) who voice the strongest backing.

The weakest overall support for trade is in Turkey (57% good), but even there over half the public accepts the proposition that international commerce is good for the society. Notably, enthusiasm for trade has eroded significantly in Italy. In 2002, 80% of Italians said trade was good for the country. That backing fell to 68% in 2007 and to 59% by 2014.

2. Trade Creates Jobs

One reason global publics may believe that trade is good for their country is that, by medians of nearly three-to-one, they hold the view that trade with other nations leads to job creation in their country rather than job loss.

One reason global publics may believe that trade is good for their country is that, by medians of nearly three-to-one, they hold the view that trade with other nations leads to job creation in their country rather than job loss.

Trade’s impact on jobs has long been one of the most controversial issues surrounding globalization. But such concern is largely limited to publics in advanced economies. In developing economies, by a median of 66% to 17%, publics hold the view that trade with other countries increases employment instead of destroying jobs. Publics in emerging markets, by a median of 52% to 19%, agree. In advanced economies, however, there is less belief that trade leads to more employment — 44% say it does, while 33% hold the view that it results in job losses. In the U.S., Americans who say joblessness is a very big problem are the most likely to voice the opinion that trade will lead to job losses.

Education plays a role in such views. In 17 nations better educated people are significantly more likely than less educated ones to think trade creates employment opportunities. This is particularly the case in Peru, the UK, Mexico, Pakistan and Spain. But in only five societies – including France, Spain and the UK – are less educated people more likely to say trade destroys jobs.2

3. Trade Raises Wages

By roughly two-to-one, global publics also say trade increases wages rather than lowers them.

By roughly two-to-one, global publics also say trade increases wages rather than lowers them.

Publics in developing countries are most likely to voice this view. A median of more than half (55%) say such commerce raises incomes, while just 20% hold that it decreases wages. Emerging market opinion is similar: 45% say trade boosts take home pay, 20% contend that it undermines wages.

Those surveyed in advanced economies see things quite differently. A median of just a quarter expresses the view that trade increases wages, while about a third (35%) says it lowers income. More people in advanced economy publics (33%) voice the opinion that trade makes no difference to wages than in emerging (24%) and developing countries (14%).

Ugandans (79%), Bangladeshis (78%), Lebanese (77%), Tunisians (73%) and Vietnamese (72%) are the most likely to associate trade with rising wages.

Those who are most likely to hold the view that trade hurts wages are Italians (52%), Greeks (49%), French (47%), Americans (45%) and Colombians (43%).

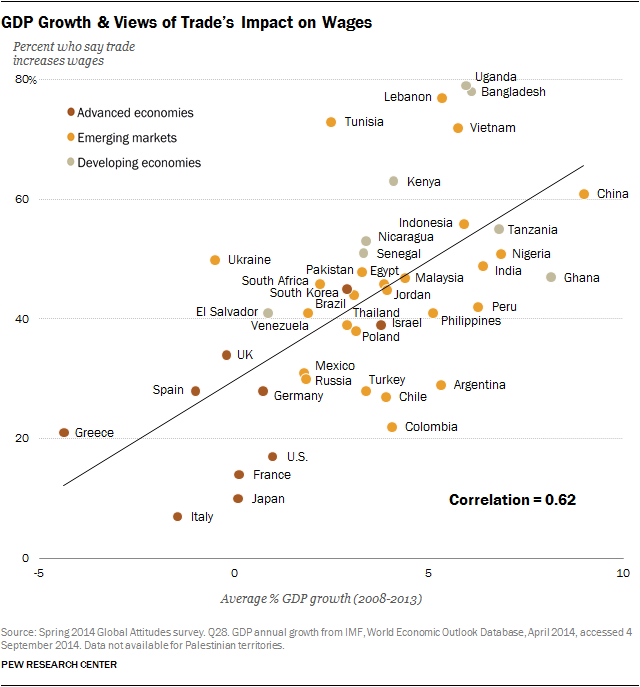

There is a strong relationship between the recent performance of the economy and views on the impact of trade on wages. The faster an economy grew on average between 2008 and 2013, the greater likelihood that the public holds the view that trade boosts wages.

4. Trade and Prices

It is a fundamental principle of modern free market economics that trade enhances competition and thus enables consumers to enjoy lower prices than they would otherwise have to pay if they depended solely on domestic production of the goods and services that they consume.

It is a fundamental principle of modern free market economics that trade enhances competition and thus enables consumers to enjoy lower prices than they would otherwise have to pay if they depended solely on domestic production of the goods and services that they consume.

Among the publics surveyed, only about one-in-four – a global median of just 26% – believes that economic theory. A median of 42% says trade actually increases prices. And 20% say it makes no difference to price levels.

In only one country, Israel (58%), does a majority accept economists’ proposition that trade leads to price cuts. In 13 nations – including major economies such as China (58%), Indonesia (58%) and Brazil (55%) – at least half the public voices the view that trade contributes to price rises.

Publics in Africa (median of 50%) and Asia (48%) are the most likely to say trade raises price levels. Europeans (35%), people in the Middle East (33%) and Americans (32%) are among the least likely to blame trade.

It would appear that economic literacy has little to do with public views on the relationship between trade and prices, at least to the extent that an understanding of economic theory is related to educational attainment. In just 10 nations do better educated people buy the argument that trade lowers prices. Notably, in a number of emerging and developing countries – Pakistan, Peru, the Palestinian territories, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, El Salvador, Malaysia and Mexico – it is better educated people who are of the opinion that trade leads to higher prices.

5. Build Here, Don’t Buy Here

Foreign investment has long been considered by many economists to be more important economically than trade. Foreign direct investment, either through the construction of new plants or through the acquisition of existing companies (as opposed to the purchase of stocks and bonds abroad), is fairly long lasting, while trade volumes can change from year to year. Much trade is between divisions of the same company, so foreign investment often drives international trade as firms exchange components and services between their affiliates. And foreign investment leads to the broad dissemination of technologies and production practices, benefiting the recipients of such investment in intangible ways.

Foreign investment has long been considered by many economists to be more important economically than trade. Foreign direct investment, either through the construction of new plants or through the acquisition of existing companies (as opposed to the purchase of stocks and bonds abroad), is fairly long lasting, while trade volumes can change from year to year. Much trade is between divisions of the same company, so foreign investment often drives international trade as firms exchange components and services between their affiliates. And foreign investment leads to the broad dissemination of technologies and production practices, benefiting the recipients of such investment in intangible ways.

Publics are of two minds about foreign direct investment. A global median of 74% approve of foreign firms building new factories in their country, sometimes referred to as greenfield investments, because these can mean new jobs and greater economic activity. But they are divided (45% good, 47% bad) about foreign companies buying local enterprises, which can mean new management, a new business culture and possible company consolidation with attendant job losses.

The differences in preferences are quite striking. A median of more than eight-in-ten in developing economies (85%) see greenfield investment as positive, but only 57% give a thumbs up to foreign-led mergers and acquisitions (M&A), a 28 percentage point difference.

Among developing nations, African countries are the most supportive of foreigners investing in their economies. Overwhelming majorities in all five African developing economies say foreign greenfield investment is good. And roughly half or more hold the view that foreign acquisitions of domestic firms is beneficial. Among these African publics, Kenyans (66% foreign M&A is good, 88% foreign greenfield is good) and Tanzanians (68%, 84%) are particularly supportive of both types of foreign capital inflows.

In emerging markets, a median of 70% backs foreigners building new plants in their country, but just 44% say foreigners buying local firms is a good thing, a 26 point difference. The emerging market BRICS economies –Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa– are generally supportive of foreign investment with two exceptions: only 38% of Russians and 39% of Chinese say foreign acquisitions are good for their country. Notably, Indians back both forms of foreign investment (68% greenfield, 56% foreign M&A), despite the fact that their government has long limited foreign investors’ access to the Indian economy.

In emerging markets, a median of 70% backs foreigners building new plants in their country, but just 44% say foreigners buying local firms is a good thing, a 26 point difference. The emerging market BRICS economies –Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa– are generally supportive of foreign investment with two exceptions: only 38% of Russians and 39% of Chinese say foreign acquisitions are good for their country. Notably, Indians back both forms of foreign investment (68% greenfield, 56% foreign M&A), despite the fact that their government has long limited foreign investors’ access to the Indian economy.

In advanced economies, nearly three-quarters (74%) support greenfield foreign investment, but only about a third (31%) say foreign M&A is good for their country, a 43 point spread in public opinion. The Germans and Japanese are among the most opposed to foreigners investing in their countries despite the fact that Germany and Japan are two of the largest suppliers of outward investment flows. Overwhelming majorities of Germans (79%) and Japanese (76%) say foreign takeovers of national companies are bad for the local economy. And roughly a third of the publics in those countries are also opposed to greenfield foreign investment (Germany 33% and Japan 34%).

American sentiment toward foreign investment is mixed: 75% say foreign investment in new plants in the United States is a good thing for the U.S. economy, but just 28% believe that foreign acquisition of firms in the U.S. is beneficial.

6. Implications for TPP and TTIP

Major trading nations are currently involved in negotiating two mega-regional trade agreements: The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

TPP involves the United States, Japan and ten other nations on both sides of the Pacific Ocean, which account for nearly two-fifths of world GDP and one-third of world trade.

TPP involves the United States, Japan and ten other nations on both sides of the Pacific Ocean, which account for nearly two-fifths of world GDP and one-third of world trade.

TTIP involves the United States and the 28 nations of the European Union. Together they account for about half of the global economy and nearly a third of world trade flows.

The 2014 Pew Research survey polled seven of the 12 TPP participants. In each of these nations, robust majorities say trade is good for their countries. Public backing for foreign companies building factories in their nations is nearly as strong. But there is far less faith in other purported benefits of trade. A median of just 52% say trade generates new jobs and only 50% support foreign-led mergers and acquisitions of domestic firms. Just 27% accept economists’ argument that trade lowers prices. And a median of only 31% say international commerce leads to increased wages.

The Vietnamese are the most enthusiastic backers of both trade and investment among the TPP nations surveyed, followed by Malaysians.

Notably, some of the weakest support for both trade and foreign investment, and some of the greatest skepticism about its impact, exists in Japan and the United States, the two pivotal TPP nations that together account for the lion’s share of both the economic activity and trade between the dozen countries involved. Just 10% of Japanese and 17% of Americans say trade increases wages. Only 15% of Japanese and 20% of Americans say it grows jobs. And just 17% of Japanese and 28% of Americans favor foreign acquisition of domestic firms. In each of these cases, Japanese and American support is the lowest among the TPP nations surveyed.

The survey also polled eight countries negotiating the TTIP. As with the TPP nations, overwhelming majorities in both Europe and the U.S. hold the view that trade is good for their economy. But, just as with TPP, there is far less faith in the purported benefits of trade. A median of 44% in the TTIP countries surveyed say international commerce creates jobs. A median of only 26% hold the view that it lowers prices. And a median of just 25% believe it increases wages.

The “I” in TTIP stands for investment. The U.S. and Europe are each other’s primary source and destination for foreign direct investment. And boosting that trans-Atlantic investment further is one of the main objectives of the negotiation. Publics on both sides of the Atlantic are of two minds about such a goal, however. A median of 75% say foreign investment is a good thing if it leads to construction of new plants in their country. But just 32% voice the view that foreigners buying companies in their country is good.

Among the TTIP countries, the Italians are the most wary of the benefits of both international commerce and foreign investment. Only 13% say trade creates jobs, just 7% see it increasing wages and 23% voice the view that foreign firms buying Italian companies is a good thing.

Among the TTIP countries, the Italians are the most wary of the benefits of both international commerce and foreign investment. Only 13% say trade creates jobs, just 7% see it increasing wages and 23% voice the view that foreign firms buying Italian companies is a good thing.

Notably, 79% of Germans say foreign-led M&A is bad for the country and 33% even view foreigners building plants in Germany in a negative light. Such opposition to foreign investment is the highest among the TTIP countries surveyed.

Such doubts about the specific benefits of trade and foreign investment do not, necessarily, translate into public opposition to TPP and TTIP. An April 2014 Pew Research survey found that 75% of Germans said increasing trade with the United States would be a good thing and 72% of Americans believed that growing commerce with the European Union would be good. Over half of Germans (55%) and Americans (53%) thought TTIP would be good for their country. With regard to TPP, 74% of Americans said boosting trade with Japan, the principal other economy in the TPP negotiation, would be beneficial. And 55% of Americans favored TPP.