Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto has been praised internationally for his ambitious reforms of everything from the energy sector to education to telecommunications, but a new Pew Research Center survey in Mexico finds that domestically his positive image is faltering and a key component of his political agenda – economic reform – is decidedly unpopular.

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto has been praised internationally for his ambitious reforms of everything from the energy sector to education to telecommunications, but a new Pew Research Center survey in Mexico finds that domestically his positive image is faltering and a key component of his political agenda – economic reform – is decidedly unpopular.

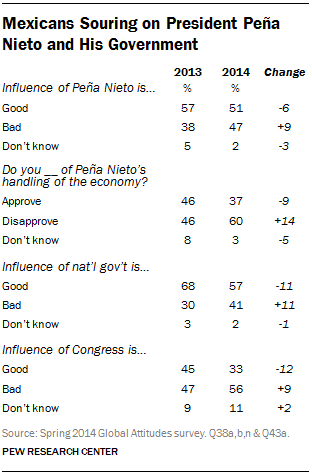

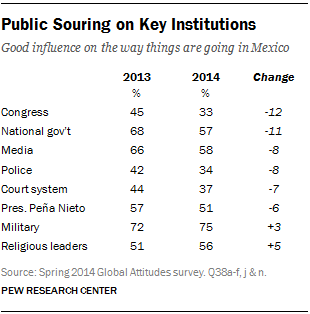

Mexicans today are evenly divided in their opinion of Peña Nieto, as negative ratings of the president’s influence have increased by nine percentage points in the past year to 47%. Similarly, negative views of the national government and Congress, both led by Peña Nieto’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), have gone up by roughly the same share over the past year, though 57% still say the national government has a positive influence.

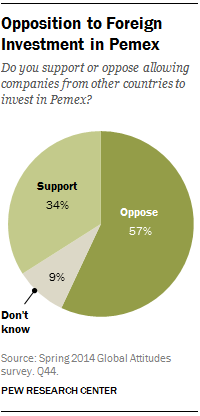

Amid Peña Nieto’s attempts at fiscal reform, the country’s economy continues its sluggish pace, with 1% GDP growth in 2013 and less than 3% growth projected for 2014. Six-in-ten Mexicans express dissatisfaction with their country’s economy and the same percentage disapprove of Peña Nieto’s performance on economic matters. A major piece of Peña Nieto’s economic platform is to allow foreign investment in the Mexican oil and gas industry, a reform that reverses the 76-year monopoly of the state-owned petroleum company, Petróleos Mexicanos, better known as Pemex. Mexican control of the country’s natural resources, which for many Mexicans is synonymous with Pemex, is a matter of national pride. The survey asked whether foreign investment in Pemex should be allowed, and a majority (57%) opposes the idea. Peña Nieto’s efforts to combat political corruption also receive poor marks – 54% disapprove of how he’s handled this issue.

Despite these negative reviews, the public still has a significantly more positive image of their president (51% favorable) than of other major political figures, a rating driven in large part by overwhelming support among PRI partisans (83% favorable). More than half of Mexicans say that Peña Nieto is doing well at dealing with the education system (55%) and fighting organized crime and drug traffickers (53%). And a plurality (45%) thinks the national government is making progress in its campaign against the drug cartels, up from 37% last year.

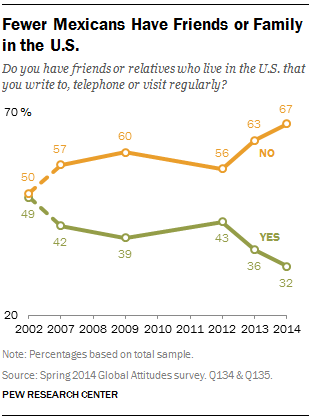

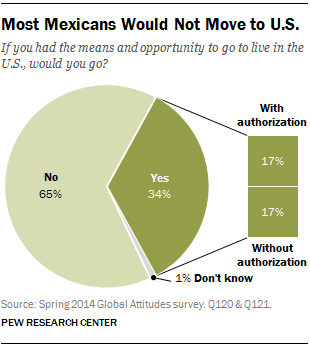

These are among the key findings from the latest survey in Mexico by the Pew Research Center, which is based on face-to-face interviews conducted among a representative sample of 1,000 randomly selected adults from across the country between April 21 and May 2, 2014. The poll also finds that as the immigration debate rages on in the U.S., a plurality of Mexicans (44%) believe life is better north of the border for those who migrated from Mexico. And roughly a third (34%) still say they would move to the U.S. if they had the opportunity, including 17% of Mexicans who would do so without authorization. Nonetheless, the declining net rate of migration from Mexico to the U.S. is reflected in the percentage of Mexicans who report having a friend or family member living in the U.S. – 32% today, down from 42% in 2007.

These are among the key findings from the latest survey in Mexico by the Pew Research Center, which is based on face-to-face interviews conducted among a representative sample of 1,000 randomly selected adults from across the country between April 21 and May 2, 2014. The poll also finds that as the immigration debate rages on in the U.S., a plurality of Mexicans (44%) believe life is better north of the border for those who migrated from Mexico. And roughly a third (34%) still say they would move to the U.S. if they had the opportunity, including 17% of Mexicans who would do so without authorization. Nonetheless, the declining net rate of migration from Mexico to the U.S. is reflected in the percentage of Mexicans who report having a friend or family member living in the U.S. – 32% today, down from 42% in 2007.

Mexicans Displeased with National Conditions

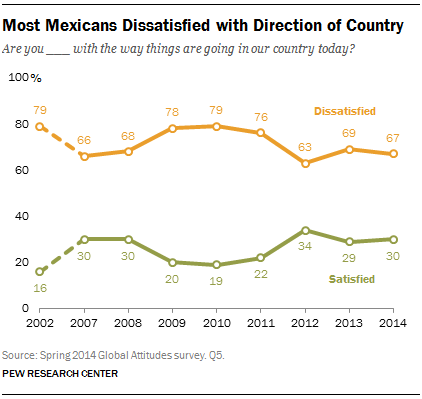

A majority of Mexicans remain unhappy with conditions in their country. Fully two-thirds are dissatisfied with the way things are going in Mexico today. Only 30% are satisfied with the country’s direction. This is largely unchanged from last year (29% satisfied, 69% dissatisfied) and continues a trend of general malaise going back to when the question was first asked in 2002.

A majority of Mexicans remain unhappy with conditions in their country. Fully two-thirds are dissatisfied with the way things are going in Mexico today. Only 30% are satisfied with the country’s direction. This is largely unchanged from last year (29% satisfied, 69% dissatisfied) and continues a trend of general malaise going back to when the question was first asked in 2002.

Majorities in all regions of Mexico convey displeasure, though those in the South (73% dissatisfied) and the Greater Mexico City area (78%) are especially disgruntled.1 Residents of urban areas (71%) are also particularly frustrated. People who identify with the PRI (45% satisfied) are happier than other partisans, though 52% of PRI supporters still express dissatisfaction with Mexico’s current course.

Mexicans are similarly disappointed about the state of the economy. Six-in-ten think the current economic situation in their country is bad, including roughly a quarter (27%) who say it is very bad. Just four-in-ten give the economy a positive rating. Yet Mexicans remain optimistic about the future – half believe the economy will improve over the next 12 months. A quarter think the economy will remain the same as it is now, with a similar number (24%) saying it will worsen over the next year.

Most Still Worried about Crime

Crime continues to be the biggest concern of the Mexican public.. An overwhelming 79% say crime is a very big problem in their country, roughly the same as last year (81%). About seven-in-ten Mexicans also worry about corrupt political leaders (72%), drug cartel-related violence (72%), water pollution (70%) and air pollution (69%). Just over six-in-ten say corrupt police officers (63%) are a top problem.

Crime continues to be the biggest concern of the Mexican public.. An overwhelming 79% say crime is a very big problem in their country, roughly the same as last year (81%). About seven-in-ten Mexicans also worry about corrupt political leaders (72%), drug cartel-related violence (72%), water pollution (70%) and air pollution (69%). Just over six-in-ten say corrupt police officers (63%) are a top problem.

About six-in-ten (58%) say food safety is a very big problem, and 54% say the same about health care. Roughly four-in-ten or fewer are troubled by people leaving for jobs in other countries (38%), traffic (33%) and electricity shortages (31%).

Concern about poor quality schools is widespread in Mexico (52%), but anxiety over the school system has dropped 11 percentage points in the last 12 months (from 63% in 2013). These fears seem to have peaked with the arrest of Elba Esther Gordillo, the influential head of the Mexican teachers’ union (SNTE) in February 2013, just months before Peña Nieto signed sweeping education reforms into law in September.

Concern has also ebbed about people leaving for jobs in other countries. In 2013, more than half (53%) believed this was a very big problem; in 2014 just 38% say the same.

Growing Discontent with Government

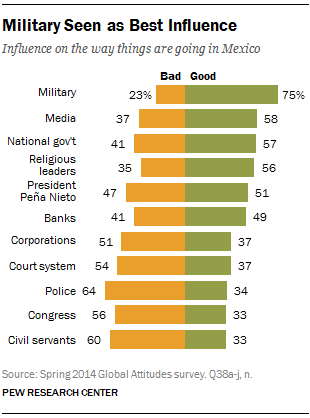

The military continues to receive high marks from the Mexican public. Three-quarters say the military has a good influence on the way things are going in the country; only 23% disagree. This opinion remains virtually unchanged from last year, when 72% praised the military’s influence.

The military continues to receive high marks from the Mexican public. Three-quarters say the military has a good influence on the way things are going in the country; only 23% disagree. This opinion remains virtually unchanged from last year, when 72% praised the military’s influence.

Half or more also believe the media, national government, religious leaders and President Peña Nieto have a positive impact on the nation.

Meanwhile, fewer than four-in-ten give positive assessments of some other key groups within the country. Institutions and groups receiving the least amount of praise include corporations, the court system, the police, Congress and civil servants. Half or more say each of these has a bad influence on the way things are going in Mexico.

Residents of Mexico’s urban areas are especially displeased, expressing more negative views than rural inhabitants when it comes to the national government, media, religious leaders, corporations and the Congress.

Residents of Mexico’s urban areas are especially displeased, expressing more negative views than rural inhabitants when it comes to the national government, media, religious leaders, corporations and the Congress.

Since last year, positive views of various groups have declined significantly. Congress saw a 12 percentage point decrease in ratings, from 45% saying it had a good influence on the country in 2013 to 33% in 2014. The national government, while still viewed in a positive light, experienced a drop of 11 points in 12 months. Mexicans also give less favorable reviews to the media (-8 percentage points), police (-8), court system (-7) and President Peña Nieto (-6) than they did in 2013.

None of the three main political parties in Mexico receive overwhelming public support. The centrist PRI, which is currently in power and ruled for 70 years prior to 2000, fares the best, with 47% expressing a favorable opinion and an equal number holding an unfavorable one (47%). Those in urban areas (51%) have a more negative opinion of the PRI than their rural counterparts (34%). A majority of the Mexican public (63%) gives negative marks to the National Action Party (PAN), the conservative opposition party.2 Only 30% view this party favorably. The left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) fares even worse, with just a quarter giving a positive assessment of the group while 66% rate them negatively, including 41% who have a very unfavorable opinion.

Peña Nieto Gets Mixed Reviews

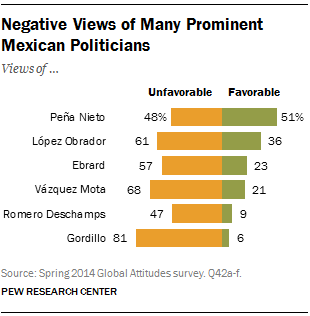

Mexicans are divided over President Enrique Peña Nieto, with 51% expressing a favorable opinion and 48% viewing him unfavorably, including 30% who give a very unfavorable assessment. Since 2012, negative attitudes toward the president have increased 10 percentage points. Mexicans age 50 and older, those who live in rural areas, and residents of Mexico’s Central region have a more positive impression of the president.

Mexicans are divided over President Enrique Peña Nieto, with 51% expressing a favorable opinion and 48% viewing him unfavorably, including 30% who give a very unfavorable assessment. Since 2012, negative attitudes toward the president have increased 10 percentage points. Mexicans age 50 and older, those who live in rural areas, and residents of Mexico’s Central region have a more positive impression of the president.

Peña Nieto receives the highest rating among the leaders asked about on the survey. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the PRD’s candidate during the 2012 presidential elections who recently broke away to found his own party, the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), garners positive ratings from just 36% of the public. About six-in-ten (61%) view him negatively, relatively unchanged from 2012.

Marcelo Ebrard, who served as mayor of Mexico City for six years, also remains unpopular. Only 23% express favorable views of this PRD-aligned politician, while 57% give him a negative rating.

Roughly two-in-ten (19%) offer no opinion. Positive ratings of Ebrard have diminished since 2011 when 35% had a favorable view.

The PAN’s first female candidate for president, Josefina Vázquez Mota, is disliked by 68% of the Mexican public. Only about two-in-ten rate this former education minister favorably, a decline of 15 percentage points since 2012, when she ran for president.

Carlos Romero Deschamps receives negative marks from 47% of Mexicans, though 44% express no opinion. A union executive associated with Pemex-gate, a corruption scandal involving the state-owned oil monopoly Pemex, he picks up only a 9% favorability rating.

The former leader of the Mexican teachers’ union (SNTE), Elba Esther Gordillo, is the least popular figure included in the survey. Roughly eight-in-ten (81%) voice displeasure with Gordillo, who was arrested last year for allegedly embezzling over $150 million from her union. Fully 69% of Mexicans have a very unfavorable view of her.

Negative Ratings on Economy

President Peña Nieto faces mixed reviews on his domestic policy agenda. Peña Nieto has set out to implement substantial economic reforms. Yet, the president’s toughest marks come on his management of the economy, where only 37% think he has done a good job. Fully 60% disapprove, 14 percentage points higher than last year. This could reflect the slow economic activity of 2014 thus far, which caused the Mexican Central Bank to revise down its growth forecast earlier this year.

President Peña Nieto faces mixed reviews on his domestic policy agenda. Peña Nieto has set out to implement substantial economic reforms. Yet, the president’s toughest marks come on his management of the economy, where only 37% think he has done a good job. Fully 60% disapprove, 14 percentage points higher than last year. This could reflect the slow economic activity of 2014 thus far, which caused the Mexican Central Bank to revise down its growth forecast earlier this year.

As part of his economic agenda, Peña Nieto proposed allowing private international investment in the oil and gas industry for the first time in over 75 years, legislation that was recently finalized by the Mexican Congress. Under the new laws, private companies will be able to conduct oil exploration in Mexico, including through partnerships with Pemex, the state-owned petroleum company. The survey asked whether respondents support or oppose allowing companies from other countries to invest in Pemex. A majority of Mexicans (57%) oppose opening up Pemex to foreign businesses. Only about a third (34%) approve. Even PRI supporters are divided (44% support vs. 46% oppose).

Another key component of Peña Nieto’s platform has been an attempt to increase government transparency and address political corruption by reforming the Federal Institute for Access to Public Information and Data Protection (IFAI) – an agency that is responsible for resolving disputes over requests for public information. Only about four-in-ten (42%) think the president is doing a good job battling corruption, compared with 54% who dislike his handling of the situation. This is a six percentage point increase in disapproval since last year on an issue that 72% of Mexicans consider a very big problem.

But not all of Peña Nieto’s policies are disliked by the public. A majority (55%) approves of the president’s approach to education, which includes establishing new standards for hiring teachers and taking power away from the influential SNTE teachers’ union. However, a sizable 41% still .

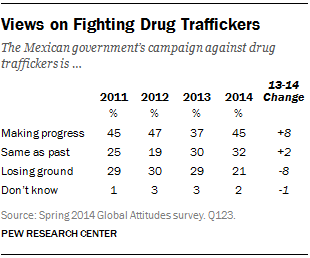

More than half (53%) applaud Peña Nieto’s performance in the fight against organized crime and drug traffickers. (The survey was conducted two months after the arrest in February 2014 of notorious drug kingpin Joaquín Guzmán Loera, known as El Chapo.) And the Mexican public is optimistic about the government’s overall gains in its campaign to fight drug traffickers, with a 45%-plurality saying the Peña Nieto administration has made progress. This represents an eight point increase since last year, though the 2014 level of confidence is comparable to pre-2013 findings. Only about two-in-ten (21%) believe the government is losing ground in this battle, significantly less than in previous years. And 32% say things are the same as they have been in the past. As has been the case in prior surveys, a broad majority of Mexicans (88%) support using the Mexican army to fight drug traffickers.

More than half (53%) applaud Peña Nieto’s performance in the fight against organized crime and drug traffickers. (The survey was conducted two months after the arrest in February 2014 of notorious drug kingpin Joaquín Guzmán Loera, known as El Chapo.) And the Mexican public is optimistic about the government’s overall gains in its campaign to fight drug traffickers, with a 45%-plurality saying the Peña Nieto administration has made progress. This represents an eight point increase since last year, though the 2014 level of confidence is comparable to pre-2013 findings. Only about two-in-ten (21%) believe the government is losing ground in this battle, significantly less than in previous years. And 32% say things are the same as they have been in the past. As has been the case in prior surveys, a broad majority of Mexicans (88%) support using the Mexican army to fight drug traffickers.

Fewer Mexicans Have Friends or Family in the U.S.

Net migration from Mexico to the U.S. – including unauthorized migration – fell sharply between 2005 and 2010.3 This decline is reflected in the percentage of Mexicans who report knowing someone in the U.S. Today, 32% of Mexicans say they have friends or relatives they regularly communicate with or visit in the U.S., a 10 percentage point decline since 2007.

The number of Mexicans who think a better life awaits those who move to the U.S. has also decreased since 2007 (51% in 2007 vs. 44% in 2014), though this is still the plurality view. About a third (32%) now think life is neither better nor worse north of the border, and only 18% believe life is worse. Roughly half of young people age 18-29 are more likely to see the U.S. as a land of opportunity (51% better life), compared with only 40% of Mexicans age 50 or older.

Still, the percentage of Mexicans who are inclined to move to the U.S. remains steady at roughly a third (34%). People who want to migrate north are split between those who would move without authorization (17%) and those who would move only with legal authority (17%). Nearly two-thirds of Mexicans (65%) say they would not go live in the U.S., even if they had the means and ability to do so. Men (38% would move) and young people age 18-29 (51%) are particularly likely to say they would go to the U.S. if they could.

Still, the percentage of Mexicans who are inclined to move to the U.S. remains steady at roughly a third (34%). People who want to migrate north are split between those who would move without authorization (17%) and those who would move only with legal authority (17%). Nearly two-thirds of Mexicans (65%) say they would not go live in the U.S., even if they had the means and ability to do so. Men (38% would move) and young people age 18-29 (51%) are particularly likely to say they would go to the U.S. if they could.