Nearly a year of tumult and violence has drained Egyptians of their optimism and battered the images of key players in the post-Mubarak era, according to a new survey by the Pew Research Center. As a controversial presidential election approaches, 72% of Egyptians are dissatisfied with their country’s direction, and although most still want democratic rights and institutions, confidence in democracy is slipping. In a shift from previous years, Egyptians are now more likely to say that having a stable government (54%) is more important than having a democratic one (44%).

Nearly a year of tumult and violence has drained Egyptians of their optimism and battered the images of key players in the post-Mubarak era, according to a new survey by the Pew Research Center. As a controversial presidential election approaches, 72% of Egyptians are dissatisfied with their country’s direction, and although most still want democratic rights and institutions, confidence in democracy is slipping. In a shift from previous years, Egyptians are now more likely to say that having a stable government (54%) is more important than having a democratic one (44%).

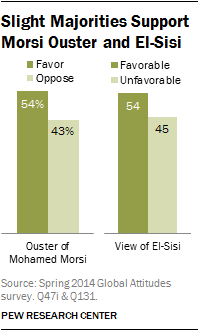

Last July’s military takeover wins support from a slender majority: 54% favor it; 43% oppose. And while the next president is almost certain to be Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, the former general who has been the most powerful figure in the country since last year’s overthrow of the government, the new poll finds that his popularity is limited. Sisi receives a favorable rating from 54% of Egyptians, while 45% view him unfavorably, a more mixed review than many media reports from Egypt over the last year might suggest.

Meanwhile, ratings have declined for former President Mohamed Morsi, the man Sisi removed from power. Currently, 42% express a favorable opinion of Morsi, down from 53% in last year’s survey, which was conducted just weeks before his ouster. However, the fact that roughly four-in-ten Egyptians still hold a positive opinion of the jailed former president may be a surprise to many, given the government’s crackdown on Morsi’s organization, the Muslim Brotherhood.

Meanwhile, ratings have declined for former President Mohamed Morsi, the man Sisi removed from power. Currently, 42% express a favorable opinion of Morsi, down from 53% in last year’s survey, which was conducted just weeks before his ouster. However, the fact that roughly four-in-ten Egyptians still hold a positive opinion of the jailed former president may be a surprise to many, given the government’s crackdown on Morsi’s organization, the Muslim Brotherhood.

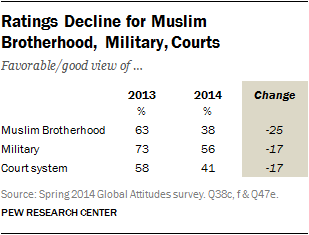

Ratings for the Brotherhood have also dropped, although again about four-in-ten Egyptians continue to have a positive view of the nearly 90-year-old group, which has been banned by the current regime and seen most of its leaders arrested.

Attitudes toward other major institutions in the country have also turned more negative over the last year. Most notably, support for the military is down. Fifty-six percent say the military is having a good impact on the country and 45% say it is having a negative influence. A year ago, 73% described the military influence as positive and 24% as negative. In a 2011 poll, conducted weeks after the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak, 88% gave the military a good rating, while only 11% assigned it a negative one.

The image of the courts, which have issued numerous controversial verdicts in the past year, has also suffered. Now, just 41% believe the court system is having a positive impact on the country; 58% say the impact is negative. Last year, opinions were the exact opposite: 58% saw the courts positively, 41% negatively.

These are among the major findings from the latest survey of Egypt by the Pew Research Center. Based on face-to-face interviews conducted between April 10 and April 29, 2014, among a representative sample of 1,000 randomly selected adults from across the country, the poll also finds that relatively secular and liberal leaders and groups receive mostly poor ratings. Hamdeen Sabahi, often described as a Nasserist or leftist politician, and the only major figure challenging Sisi in the presidential race, is seen favorably by just 35% of Egyptians, down from 48% in 2013.

Attitudes towards Mohamed ElBaradei, a former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency who supported the removal of both Mubarak in 2011 and Morsi in 2013, have soured steadily since 2011. Then, 57% had a positive opinion of ElBaradei; currently, just 27% hold this view.

Meanwhile, the April 6th Movement, a largely youth-led, relatively secular group that was active in the Tahrir Square protests that led to Mubarak’s downfall, has seen its positive rating fall to 48%, compared with 2011 when seven-in-ten Egyptians regarded the group favorably.

A Dismal Public Mood

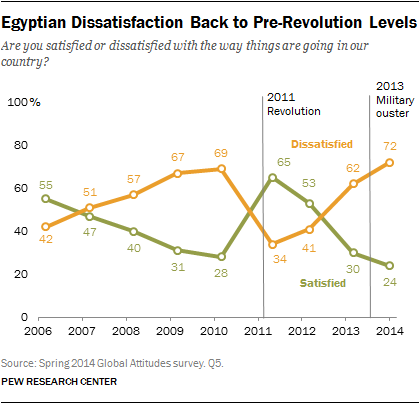

By a 3-to-1 margin, Egyptians are more dissatisfied (72%) than satisfied (24%) with their country’s direction. Dissatisfaction is up significantly from last year’s already high 62%, and in fact, is roughly the same today as it was before the revolution that removed Mubarak from office.

By a 3-to-1 margin, Egyptians are more dissatisfied (72%) than satisfied (24%) with their country’s direction. Dissatisfaction is up significantly from last year’s already high 62%, and in fact, is roughly the same today as it was before the revolution that removed Mubarak from office.

In addition to declining trust in leaders and institutions, Egyptians continue to have deep concerns about their economy. Only 21% say the economy is in good shape, essentially unchanged from last year. And the public is almost evenly divided between those who think the economy will improve over the next 12 months (31%), those who believe it will worsen (35%), and those who expect it to stay about the same (31%).

More generally, the public’s sense of optimism about the future has waned since the 2011 revolution. At that time, 57% were optimistic about the future of the country and just 16% were pessimistic. Today, there are almost equal numbers of optimists (39%) and pessimists (34%), while 22% volunteer that they are neither.

Most Still Want Democracy, but Enthusiasm Is Waning

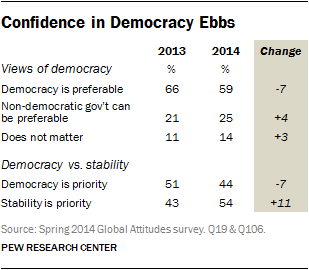

As they have in the past, most Egyptians continue to embrace the concept of democracy. Roughly six-in-ten (59%) say it is the best form of government, although this is down from 66% last year and 71% in 2011. And most still say it’s important to live in a country with basic democratic rights and institutions, but within the past year support has declined for some key pillars of democracy, such as free speech, freedom of the press, and honest, competitive elections.

And when asked which is more important, having a democratic government, even if there is a risk of instability, or having a stable government, even if there is a risk it will not be fully democratic, a narrow majority (54%) chooses stability. Forty-four percent take the other view, saying the priority should be democracy. In contrast, last year 51% prioritized democracy, while just 43% said a stable government is more important.

And when asked which is more important, having a democratic government, even if there is a risk of instability, or having a stable government, even if there is a risk it will not be fully democratic, a narrow majority (54%) chooses stability. Forty-four percent take the other view, saying the priority should be democracy. In contrast, last year 51% prioritized democracy, while just 43% said a stable government is more important.

In another notable shift this year, the Egyptian government receives poor marks for its record on protecting the freedoms of the Egyptian people.  Sixty-three percent say the government does not respect personal liberties, up from 44% in 2013.

Sixty-three percent say the government does not respect personal liberties, up from 44% in 2013.

A Sharp Division

Unsurprisingly, the ouster of Mohamed Morsi last July has emerged as a sharp dividing line in Egyptian politics.

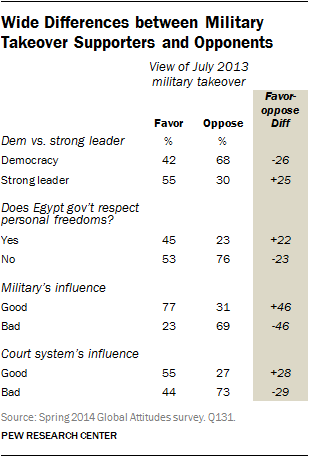

On issue after issue, there are large differences between those who favor and those who oppose Morsi’s removal from power. For instance, those who oppose the removal are more likely than its supporters to favor democracy over a strong leader. Meanwhile, people who back the ouster are more likely to say the government respects personal liberty and to give the military and the courts positive ratings.