Europe is showing signs of recovering from the double-dip recession it experienced in the wake of the economic crisis in 2008. After growing by a mere 0.2% in 2013, the economy of the 28-country European Union is expected to expand by 1.6% in 2014, according to the International Monetary Fund. The smaller euro area, those 18 nations that use the single European currency, is doing less well. The economy of the euro area continued to shrink by -0.5% in 2013 and may grow by only 1.2% in 2014. And national economic prospects vary widely. The United Kingdom’s economy is expected to expand by 2.9% in 2014, France by only 1%, Spain by 0.9% and Italy by 0.6%.

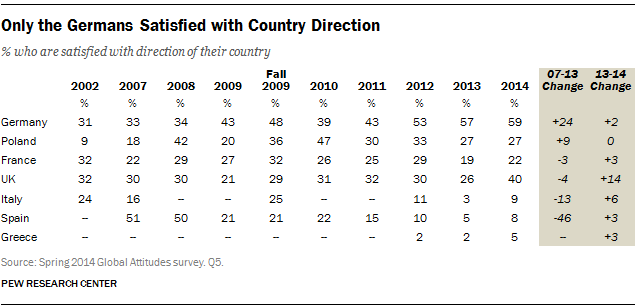

Given these economic conditions in the seventh year of the euro crisis, few Europeans are satisfied about the trajectory of their society. Just 5% of the public in Greece, 8% in Spain and 9% in Italy and only 22% in France and 27% in Poland say they are satisfied with the way things are going in their country. Such sentiment remains largely unchanged in those nations compared with 2013. And in a number of societies – France, Italy and Poland – this lack of satisfaction predates the euro crisis.

By comparison, Germans (59%) remain relatively upbeat about national conditions and are now 26 points more positive about Germany’s direction than they were in 2007.

Elsewhere, declining satisfaction seems to have halted. The greatest mood swing in Europe over the past year has occurred in the UK, where satisfaction with the nation’s direction has risen from 26% to 40%. While a majority (55%) are still dissatisfied with national conditions, negative sentiment is down 13 percentage points since 2013.

A closer look at the demography of the public’s disgruntlement reveals some notable cleavages within European society. In recent months, the news media have focused a great deal of attention on anger among those on the right of the political spectrum, especially in France and Greece. The French right (83%) is significantly more dissatisfied with the way things are going in the country than the French public on the left (70%). In Greece, it is the left (97%) that is somewhat more upset than the right (87%).

In addition, people 50 years of age and older in France (83%), Poland (76%) and the UK (60%) are much more dissatisfied than those under 30 in France (71%), Poland (65%) and the UK (37%). Similarly, those without a college degree in the UK, Poland, Germany and France are significantly more dissatisfied with the state of their nation than are people in their societies with a college degree.

Economic Sentiment Bottoms Out

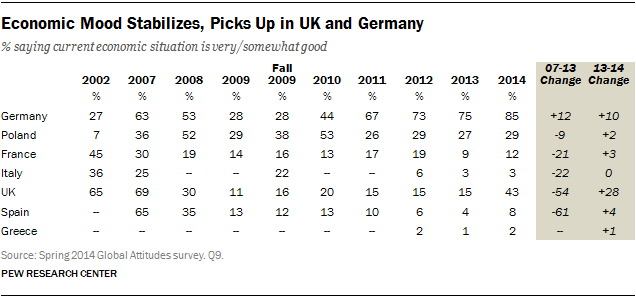

Views about national trajectory largely correspond with public sentiment about the economy. Except in Germany, European publics overwhelmingly agree that economic conditions are bad. Just 2% of Greeks, 3% of Italians, 8% of Spanish and 12% of French see their economy in a positive light. For southern Europeans, the euro crisis is clearly not over. More than nine-in-ten people in Spain, Italy and Greece have held extremely sour views about the economy for the past three years.

Nevertheless, the first signs of a turnaround in extreme displeasure with the economy may be evident in the United Kingdom and Spain. The proportion of people saying their economy is in very bad shape has shrunk by 21 percentage points in the United Kingdom (from 39% to 18%) and 16 points in Spain (from 79% to 63%).

Meanwhile, despite sluggish 0.5% growth in 2013 and modest 1.7% anticipated expansion in 2014, Germans are increasingly upbeat about their economy: 85% say economic conditions are good, up from 75% who held such views last year and just 28% who were bullish about the German economy as recently as 2009.

Again, the greatest change in economic mood is found in the United Kingdom. While 55% of the British public still say economic conditions are bad, 43% now say conditions are good, up 28 percentage points in just the past year. This change in perception was in part driven by the attitude of people 50 years of age and older. In 2013, just 11% of older British thought the economy was doing well. In 2014, 44% had a positive take on economic conditions.

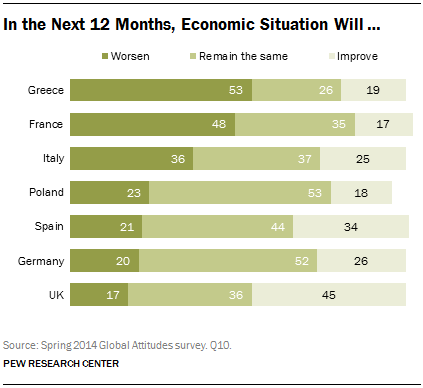

There is little optimism about the immediate future of the economy. Just 17% of the French, 18% of Poles and 19% of Greeks see things getting better in the next 12 months. Only a quarter of Germans (26%) and Italians (25%) agree.

There is little optimism about the immediate future of the economy. Just 17% of the French, 18% of Poles and 19% of Greeks see things getting better in the next 12 months. Only a quarter of Germans (26%) and Italians (25%) agree.

Yet some in Spain and the UK voice the belief that their long national economic nightmare may be coming to an end. Fully 45% of the public in the UK and 34% in Spain expect economic conditions to improve over the next year. Such optimism is up 23 points from 2013 in Britain and 11 points in Spain. Again, it is older British (50%) who are more upbeat than those ages 18 to 29 (36%).

Future Looks Less Grim

In another potentially positive sign, in a number of countries the proportion of the public that expects their economy to worsen has sharply declined.

In 2013, 61% of the French expected their economy to slow further. In 2014, only 48% are bearish. Similarly, in Greece pessimism about the future of the economy has fallen from 64% to 53%.

For many Europeans, however, expectations are that the coming year will be much like the previous one. About half of those surveyed in Poland (53%) and Germany (52%), and 44% in Spain, say economic conditions are likely to remain the same.

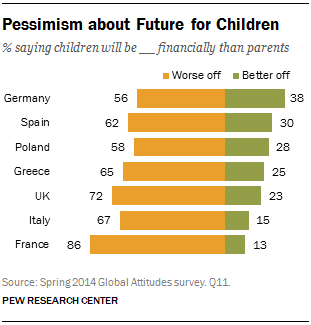

Looking ahead, many Europeans are deeply pessimistic about prospects for the next generation. More than eight-in-ten French (86%), seven-in-ten British (72%) and roughly two-thirds of Italians (67%) and Greeks (65%) say that they expect that when today’s children grow up they will be worse off financially than their parents. In most nations, such pessimism remains unchanged from 2013, suggesting that the recent uptick in economic performance has not substantially altered Europeans’ glum views about the long-term future.

Looking ahead, many Europeans are deeply pessimistic about prospects for the next generation. More than eight-in-ten French (86%), seven-in-ten British (72%) and roughly two-thirds of Italians (67%) and Greeks (65%) say that they expect that when today’s children grow up they will be worse off financially than their parents. In most nations, such pessimism remains unchanged from 2013, suggesting that the recent uptick in economic performance has not substantially altered Europeans’ glum views about the long-term future.

What limited optimism there is about the future is largely the preserve of young people and then only in a few societies. People ages 18 to 29 in Spain (42%) and the UK (40%) are more likely than older Spanish (23%) and British (19%) to say that today’s children will be better off.

One reason for Europeans’ ongoing sense of economic foreboding is their persistent concern about a number of nagging economic problems. The public remains intensely worried about joblessness, public debt, inflation and inequality. But, in line with the ever-so-slight moderation in economic gloom in some nations, the intensity of public concern about these challenges seems to be ebbing.

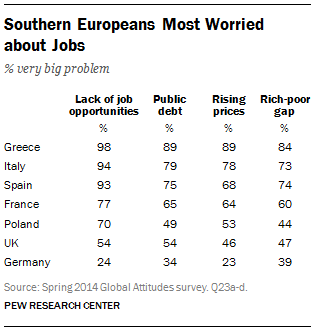

With February 2014 unemployment in the euro area at 10.6%, including 27.5% in Greece (in December 2013) and 25.6% in Spain, according to Eurostat, the lack of job opportunities remains a major public worry. More than nine-in-ten Greeks (98%), Italians (94%) and Spanish (93%) see it as a very big problem, as do more than seven-in-ten French (77%), nearly as many Poles (70%) and half of the British (54%). Only Germans (24%) lack intense concern about unemployment.

Annual EU inflation was a mere 0.6% in March 2014, down from 1.9% a year earlier, according to Eurostat. Thus, it is little wonder that intense concern – the median of those who say rising prices are a very big problem – is down four percentage points from 2013. In particular, inflation worry has dropped thirteen points in Poland, eight points in Germany, four points in France and six points in Italy.

Public debt in EU countries remains high: equal to 171.8% of GDP in Greece, 132.9% in Italy and 93.4% in Spain, according to Eurostat. And about nine-in-ten Greeks (89%), roughly eight-in-ten Italians (79%) and more than seven-in-ten Spanish (75%) are very worried. Notably, however, despite rising debt levels in a number of countries, concern has plateaued.

Public debt in EU countries remains high: equal to 171.8% of GDP in Greece, 132.9% in Italy and 93.4% in Spain, according to Eurostat. And about nine-in-ten Greeks (89%), roughly eight-in-ten Italians (79%) and more than seven-in-ten Spanish (75%) are very worried. Notably, however, despite rising debt levels in a number of countries, concern has plateaued.

Finally, there is continuing concern about the gap between the rich and the poor. A median of 60% hold the view that inequality is a very big problem. But the intensity of such concern has ebbed, down 12 points in Germany and 10 points in Poland.

Given Germans’ exuberance about the current state of their economy, it is not surprising that Germans are notably less worried than any of the other Europeans surveyed about the whole gamut of current economic problems. Contrary to the narrative propounded by many German officials – that their people have been permanently scarred by the hyperinflation of the 1920s, thus ruling out any support by Berlin for an easier monetary policy by the European Central Bank – just 23% of Germans say rising prices are a very big problem. Far more (39%) are worried about the gap between the rich and the poor.