By Bruce Stokes, Director of Global Economic Attitudes, Pew Research Center

Submitted as evidence to the Foreign Affairs Select Committee of the British House of Commons on December 17, 2013.

Overview

The “special relationship” between the United Kingdom and the United States, a concept first voiced by Winston Churchill in 1946, has always had more salience in Whitehall and Foggy Bottom than it has in the minds of the American public.

Americans have a long history of ambivalence about their role in the world. And the new “America’s Place in the World” public opinion survey by the Pew Research Center describes a United States that is neither isolationist nor protectionist, but that is increasingly inward looking on security and foreign policy issues, while more and more outward looking on economic matters.

On discreet foreign policy issues of topical bilateral concern, there is often general agreement on broad issues between the British and American publics and disagreement on specifics.

U.S. Attitudes

Growing numbers of Americans believe that U.S. global power and prestige are in decline. And support for U.S. global engagement, already near a historic low, has declined further. The public thinks that the nation does too much to solve world problems, and increasing percentages want the U.S. to “mind its own business internationally” and pay more attention to problems here at home.

Yet this reticence is not an across-the-board isolationism. Most notably, even as doubts grow about the United States’ geopolitical role, most say the benefits from U.S. participation in the global economy outweigh the risks. And support for closer trade and business ties with other nations stands at its highest point in more than a decade.

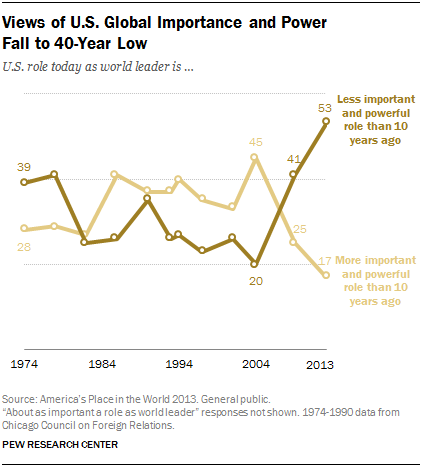

In the last year, views of U.S. global importance and power have plummeted. For the first time in surveys dating back nearly four decades, a majority (53%) says the United States plays a less important and powerful role as a world leader than it did a decade ago. The share saying the U.S. is less powerful has increased 12 points since 2009 and has more than doubled – from just 20% – since 2004. An even larger majority says the U.S. is losing respect internationally. Fully 70% say the United States is less valued than in the past, which nearly matches the level reached late in the second term of former President George W. Bush (71% in May 2008). Early last year, fewer Americans (56%) thought that the U.S. had become less respected globally.

In the last year, views of U.S. global importance and power have plummeted. For the first time in surveys dating back nearly four decades, a majority (53%) says the United States plays a less important and powerful role as a world leader than it did a decade ago. The share saying the U.S. is less powerful has increased 12 points since 2009 and has more than doubled – from just 20% – since 2004. An even larger majority says the U.S. is losing respect internationally. Fully 70% say the United States is less valued than in the past, which nearly matches the level reached late in the second term of former President George W. Bush (71% in May 2008). Early last year, fewer Americans (56%) thought that the U.S. had become less respected globally.

Moreover, foreign policy, once a relative strength for President Obama, has now become a target of substantial criticism. By a 56% to 34% margin more disapprove than approve of his handling of foreign policy. The public also disapproves, by wide margins, of his conduct in dealing with Syria, Iran, China and Afghanistan. Only on terrorism, do more approve than disapprove of Obama’s job performance (by 51% to 44%).

The public’s skepticism about U.S. international engagement has increased. Currently, 52% say the United States “should mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own.” Just 38% disagree with that statement. This is the most lopsided balance in favor of the U.S. “minding its own business” in the nearly 50-year history of asking the American public’s view on this issue.

The public’s skepticism about U.S. international engagement has increased. Currently, 52% say the United States “should mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own.” Just 38% disagree with that statement. This is the most lopsided balance in favor of the U.S. “minding its own business” in the nearly 50-year history of asking the American public’s view on this issue.

After the recent near-miss with U.S. military action against Syria, the NATO mission in Libya and lengthy wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, about half of Americans (51%) say the United States does too much in helping solve world problems, while just 17% say it does too little and 28% think it does the right amount. When those who say the U.S. does “too much” internationally are asked to describe in their own words why they feel this way, nearly half (47%) say problems at home, including the economy, should get more attention.

However, the American public expresses no reluctance about U.S. involvement in the global economy. Fully 77% say that growing trade and business ties between the United States and other countries are either very good or somewhat good for the U.S. Just 18% have a negative view. Support for increased trade and business connections has increased 24 points since 2008, during the economic recession.

By more than two-to-one, Americans see more benefits than risks from greater involvement in the global economy. About two-thirds (66%) say greater involvement in the global economy is a good thing because it opens up new markets and opportunities for growth.  Just 25% say that it is bad for the country because it exposes the U.S. to risk and uncertainty. Large majorities across education and income categories – as well as most Republicans, Democrats and independents – have positive views of increased U.S. involvement in world commerce.

Just 25% say that it is bad for the country because it exposes the U.S. to risk and uncertainty. Large majorities across education and income categories – as well as most Republicans, Democrats and independents – have positive views of increased U.S. involvement in world commerce.

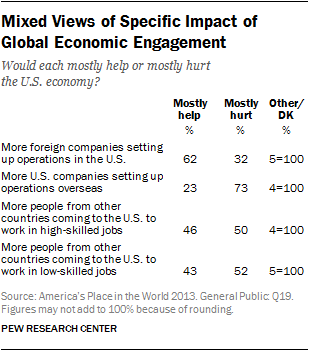

Attitudes toward foreign investment are divided, however. A majority (62%) says that more foreign companies setting up operations in the United States would mostly help the economy. But 73% think that the economy would be hurt if more U.S. companies move their operations abroad.

Demographic and Partisan U.S. Divides

The demographic and political diversity of the United States is evident in the new survey’s findings. Whites (58%) are more likely than non-whites (42%) to say America plays a less important role in the world today. And Republicans (74%) and Tea Party leaning Republicans and Independents (86%) are more likely than Democrats (33%) to see America in decline on the world stage.

There are not great demographic or partisan differences in American attitudes toward the United States minding its own business internationally. It is notable, however, that those with only a high school education or less (63%) are much more likely to hold such views that an American with a college degree or more (35%).

Similarly, there are no significant demographic or partisan differences on America’s growing business and economic ties abroad. Americans overwhelmingly see them as good for the country. It is notable, however, that contrary to the widespread perception that America Republicans are more open to foreign trade and investment than American Democrats, 83% of Democrats think global commercial ties are good for the U.S. compared with 74% of Republicans.

UK and U.S. Attitudes on Foreign Policy Topics

On a number of discreet foreign policy issues, the “special relationship” does not look that unified, at least from the public’s point of view.

On the topic “du jour” Iran, both the British (89%) and Americans (93%) oppose Tehran acquiring nuclear weapons, according to a spring 2013 Pew Research Center survey. But among those who hold such views, 64% of Americans are willing to take military action to prevent Iran have nuclear armaments, but only 48% of the British agree.

On the topic “du jour” Iran, both the British (89%) and Americans (93%) oppose Tehran acquiring nuclear weapons, according to a spring 2013 Pew Research Center survey. But among those who hold such views, 64% of Americans are willing to take military action to prevent Iran have nuclear armaments, but only 48% of the British agree.

On another Middle Eastern flash point, both Americans and British say that a way can be found for Israel and an independent Palestinian state to coexist peacefully with each other. But 53% of Americans sympathize more with Israel than with the Palestinians in their ongoing dispute, while only 19% of the British sympathize with Israel and 42% say they take neither side or have no opinion.

The British and Americans are also both generally supportive of the U.S.-led efforts to fight terrorism. In 2012 57% of the British backed such activities, as did 76% of Americans. But they disagree on one key facet of that war on terrorism: drone strikes. While 61% of Americans approve of such targeting of extremists in countries such as Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia, only 39% of the British agree.

On China, the elephant in the room in most foreign policy debates, both the British and the American publics reject the idea that China is an enemy. But about half (52%) of the Americans have an unfavorable opinion of China compared with nearly a third (31%) of the British who hold such negative views. More than half the British (53%) also say China is the world’s leading economic power. And 55% say China will eventually replace the U.S. as the world’s leading superpower. Just 36% of Americans agree. Moreover, 44% of Americans see China’s power and influence as a major threat to the United States. But only 29% of the British are so worried.

Conclusion

So the “special relationship” is not that special when it comes to public opinion. The British and American publics do broadly agree on many international issues. But they differ on the details involving fundamental foreign policy challenges.