Survey Report

After more than two decades of economic turmoil and political transition in Japan, the public’s mood is showing some decided improvement. Japan now has a strongly popular political leadership, and there are indications of a growing Japanese aspiration to play a larger security role on the world stage.

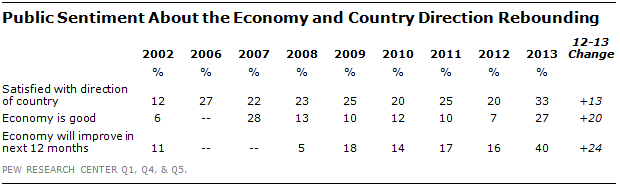

Public satisfaction with Japan’s direction is at its highest level since the Pew Research Center began regular surveys of Japan in 2002. While still sub-par, economic satisfaction in Japan has improved 20 percentage points in just the last year. And optimism about the nation’s economic trajectory over the next 12 months is second only to that found in the United States among publics in advanced economies. This may help explain why about seven-in-ten Japanese have a favorable opinion of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Looking outside of the country, Japan’s image in the region is mixed. Japan is generally seen favorably in much of Asia, but its immediate neighbors – China and South Korea – are highly skeptical of Japan. They are unfavorably disposed toward Abe. And, both the Chinese and the Koreans are critical of what they see as Japan’s failure to atone for Japanese military actions in the 1930s and 1940s.

These are some of the results from a 39-nation survey – including Japan and seven other Asia/Pacific nations – conducted by the Pew Research Center March 4 to April 6, 2013.

Economic Mood Looking Up

In absolute terms, the public mood in Japan remains mostly one of dissatisfaction. Only a third of the public is pleased with the direction of the country, barely a quarter think the economy is doing well and just four-in-ten are optimistic about the future.

But in relative terms, such sentiment has shown a dramatic improvement in just the last year. And, the Japanese are actually much more upbeat about the future than are the Europeans.

While just 33% of Japanese are content with the direction of their country, such sentiment is up 13 percentage points from 2012 and 21 points from the quite gloomy view in 2002. Moreover, Japanese satisfaction with how their nation is doing overall is better than that in South Korea, Britain or France, and comparable to that in the United States.

Only 27% of Japanese think the economy is doing well, however, hardly an endorsement of current economic conditions. But just 7% thought the economy was good in 2012 and Japanese economic sentiment has rebounded to roughly that found in 2007, before the Great Recession. Moreover, among 14 advanced economies surveyed by the Pew Research Center in 2013, in only five was the public more upbeat than the Japanese about the present economy. (For more on global economic conditions see Economies of Emerging Markets Better Rated During Difficult Times, released on May 23, 2013.)

Only 27% of Japanese think the economy is doing well, however, hardly an endorsement of current economic conditions. But just 7% thought the economy was good in 2012 and Japanese economic sentiment has rebounded to roughly that found in 2007, before the Great Recession. Moreover, among 14 advanced economies surveyed by the Pew Research Center in 2013, in only five was the public more upbeat than the Japanese about the present economy. (For more on global economic conditions see Economies of Emerging Markets Better Rated During Difficult Times, released on May 23, 2013.)

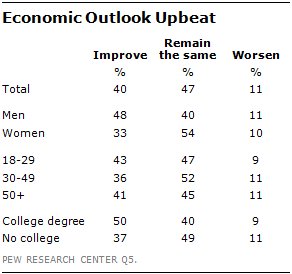

The economic optimism that the Abe government has hoped to engender through its monetary and fiscal stimulus and its promised economic reforms appears to be working. Fully 40% of Japanese think their economy will improve over the next 12 months, a measure of optimism that is up 24 points in the last year and is at its highest point in seven Pew Research Center surveys in Japan since 2002.

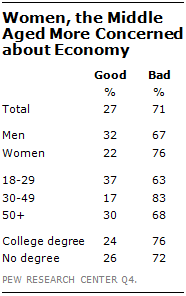

The Japanese mood about the state of the economy and its future divides along gender, age and educational lines. Men are more upbeat than women about present economic conditions and whether the economy will improve over the next 12 months. Middle-aged Japanese are particularly upset about the current state of the economy. And those with a college degree are more likely than those without a degree to think that the economy will improve.

The Japanese mood about the state of the economy and its future divides along gender, age and educational lines. Men are more upbeat than women about present economic conditions and whether the economy will improve over the next 12 months. Middle-aged Japanese are particularly upset about the current state of the economy. And those with a college degree are more likely than those without a degree to think that the economy will improve.

On a personal level Japanese are more upbeat about their own situation than they are about the national economic condition, which parallels results in other countries. Nearly four-in-ten (38%) say their personal finances are good. But just 12% envision their own economic situation improving over the next year.

However, the Japanese are deeply pessimistic about prospects for the next generation. Only 15% believe that today’s children will be better off than their parents. Among countries with advanced economies in the 2013 survey, only the French are more pessimistic than the Japanese about the future for kids.

The Japanese public, much like those in many other nations, is worried about particular economic conditions. Roughly six-in-ten think public debt (60%) and the lack of employment opportunities (58%) are very big national problems. When asked what their top priority is for action by the Abe government, 52% say create more jobs.

Prime Minister Abe Strongly Popular

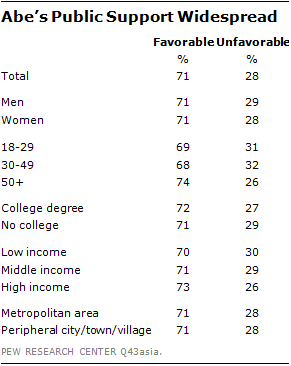

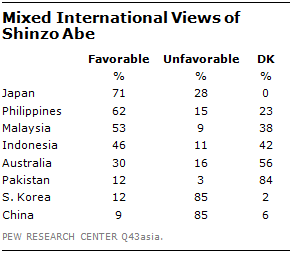

Prime Minister Abe is seen favorably by 71% of the Japanese public, with no evident gender gap, generation gap, class difference or rural-urban split in his support. This positive public assessment of the Japanese leader is widely shared among both men and women, people with a college degree and those without a degree and low, middle and high income individuals. Notably, Abe, whose Liberal Democratic Party’s original political base was overwhelmingly in rural areas, now does equally well in metropolitan areas and in peripheral cities, towns and villages of Japan.

Prime Minister Abe is seen favorably by 71% of the Japanese public, with no evident gender gap, generation gap, class difference or rural-urban split in his support. This positive public assessment of the Japanese leader is widely shared among both men and women, people with a college degree and those without a degree and low, middle and high income individuals. Notably, Abe, whose Liberal Democratic Party’s original political base was overwhelmingly in rural areas, now does equally well in metropolitan areas and in peripheral cities, towns and villages of Japan.

Increasing Support for Constitutional Change

As public sentiment about the economy changes, Japanese attitudes about the country’s strategic role in the world are evolving. For some time, there has been a robust public debate within Japan about whether Tokyo needs a military capacity and a willingness to engage in security operations commensurate with the country’s stature as the world’s third largest economy. But such ambitions have long been constrained by Japan’s post-World War II constitution.

As public sentiment about the economy changes, Japanese attitudes about the country’s strategic role in the world are evolving. For some time, there has been a robust public debate within Japan about whether Tokyo needs a military capacity and a willingness to engage in security operations commensurate with the country’s stature as the world’s third largest economy. But such ambitions have long been constrained by Japan’s post-World War II constitution.

Article 9 of the current Japanese constitution states that Japan renounces war as a means of resolving international disputes and will not maintain land, sea or air forces.

Notwithstanding such strictures, Japan does have a large Self-Defense Force. And, in recent years, these forces have been deployed internationally to provide humanitarian assistance and in peacekeeping operations sanctioned by the United Nations.

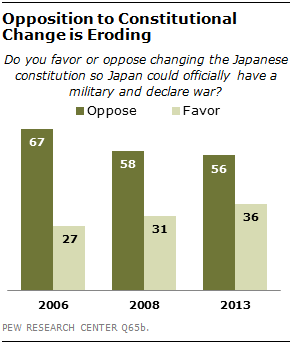

A majority of Japanese (56%) oppose changing their constitution so that Japan could officially have a military and declare war. But that opposition has declined by 11 percentage points since 2006, when 67% were against constitutional revision. Men (45%) are much more willing to support constitutional revision than are women (28%).

Asia/Pacific Views of Japan

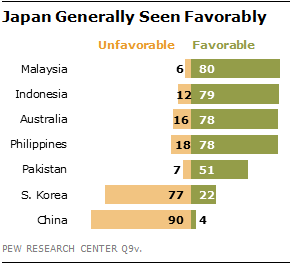

Perceptions of Japan in the Asia/Pacific region are mixed. About half or more of the publics in five of seven Asia/Pacific nations surveyed have a favorable view of Japan, most strongly so. Eight-in-ten Malaysians and nearly as many Indonesians (79%), Australians (78%) and Filipinos (78%) see Japan in a positive light.

Perceptions of Japan in the Asia/Pacific region are mixed. About half or more of the publics in five of seven Asia/Pacific nations surveyed have a favorable view of Japan, most strongly so. Eight-in-ten Malaysians and nearly as many Indonesians (79%), Australians (78%) and Filipinos (78%) see Japan in a positive light.

However, anti-Japan sentiment is quite strong in China, where 90% of the public has an unfavorable opinion of Japan, and in South Korea (77% unfavorable).

Moreover, sentiment about Japan has worsened over time in both countries. Favorability of Japan is down 25 percentage points in South Korea since 2008 and it has fallen 17 points in China since 2006. There is a notable generation gap in attitudes toward Japan in South Korea. Koreans 50 years of age and older (82% negative) are far more likely to see Japan unfavorably than are Koreans under the age of 30 (66%).

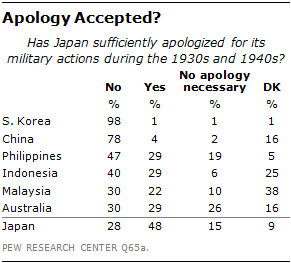

One reason for such anti-Japan sentiment in China and South Korea may be because neither the Chinese nor the Koreans believe Japan has sufficiently apologized for its military actions during the 1930s and 1940s.

One reason for such anti-Japan sentiment in China and South Korea may be because neither the Chinese nor the Koreans believe Japan has sufficiently apologized for its military actions during the 1930s and 1940s.

But the bitter legacy of that period appears to weigh more heavily on people in Northeast Asia than in Southeast Asia. While the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia were also occupied by Japan during World War II, the memory in those countries appears less powerful. A quarter of Indonesians and nearly four-in-ten Malaysians express no opinion about the need for a Japanese apology for its previous actions. And those who do have a view are generally divided over whether Japan needs to seek more forgiveness or whether the time has passed for such apologies. Such is the case in the Philippines, where 47% say Japan needs to apologize more, whereas 48% say no request for forgiveness is necessary or that Japan has sufficiently apologized.

Such sentiments stand in stark contrast to those held by many Japanese. Nearly half (48%) of Japanese think Tokyo has sufficiently apologized for its military actions in the 1930s and 1940s. Another 15% think no apology is needed. Taken together, this means a strong majority of Japanese (63%) think the past is behind them. Such views are even more prevalent among young Japanese: 73% of those aged 18 to 29 think Japan has already asked enough for forgiveness or need not apologize at all. The contrast with the views of other young Asians is quite striking: just 3% of young Koreans, 4% of young Chinese, 31% of young Indonesians and 36% of young Malaysians are willing to drop the issue of Japanese war guilt.

Generally there is no generation gap in the region on the need for Japanese atonement. But in Indonesia, younger Indonesians are actually more likely than older Indonesians to say Japan needs to apologize more: 43% of those under 30 say they want more of an apology; only 31% of those who are 50 years of age and older see such a need.

A national leader often is the symbol of his or her country abroad, buoying a nation’s image when he or she is popular with foreigners, undermining it when the leader is unpopular abroad. Prime Minister Abe’s strong showing at home is not mirrored overseas, in part because he is still not well known outside Japan. Only in the Philippines (62%) and Malaysia (53%) do more than half see Abe in a favorable light. And 38% of Malaysians and 23% of Filipinos have no view on the Japanese leader. In South Korea and China, where a greater percentage of the publics does voice an opinion, it is overwhelmingly negative: 85% of those surveyed in both nations see Abe unfavorably. This may, in part, be a byproduct of Abe’s 2012 visit to Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine for Japan’s war dead, which includes homage to some of Japan’s Class A war criminals from World War II.

A national leader often is the symbol of his or her country abroad, buoying a nation’s image when he or she is popular with foreigners, undermining it when the leader is unpopular abroad. Prime Minister Abe’s strong showing at home is not mirrored overseas, in part because he is still not well known outside Japan. Only in the Philippines (62%) and Malaysia (53%) do more than half see Abe in a favorable light. And 38% of Malaysians and 23% of Filipinos have no view on the Japanese leader. In South Korea and China, where a greater percentage of the publics does voice an opinion, it is overwhelmingly negative: 85% of those surveyed in both nations see Abe unfavorably. This may, in part, be a byproduct of Abe’s 2012 visit to Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine for Japan’s war dead, which includes homage to some of Japan’s Class A war criminals from World War II.

The Japanese public appears to be painfully aware of its image problem abroad. Six-in-ten Japanese think their country should be more respected around the world than it is.