Overview

The European Union is the new sick man of Europe. The effort over the past half century to create a more united Europe is now the principal casualty of the euro crisis. The European project now stands in disrepute across much of Europe.

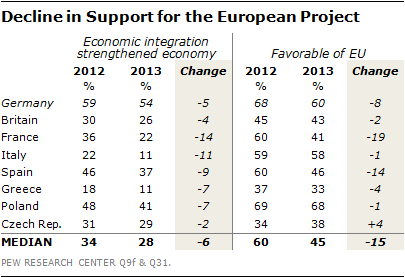

Support for European economic integration – the 1957 raison d’etre for creating the European Economic Community, the European Union’s predecessor – is down over last year in five of the eight European Union countries surveyed by the Pew Research Center in 2013. Positive views of the European Union are at or near their low point in most EU nations, even among the young, the hope for the EU’s future. The favorability of the EU has fallen from a median of 60% in 2012 to 45% in 2013. And only in Germany does at least half the public back giving more power to Brussels to deal with the current economic crisis.

Support for European economic integration – the 1957 raison d’etre for creating the European Economic Community, the European Union’s predecessor – is down over last year in five of the eight European Union countries surveyed by the Pew Research Center in 2013. Positive views of the European Union are at or near their low point in most EU nations, even among the young, the hope for the EU’s future. The favorability of the EU has fallen from a median of 60% in 2012 to 45% in 2013. And only in Germany does at least half the public back giving more power to Brussels to deal with the current economic crisis.

The sick man label – attributed originally to Russian Czar Nicholas I in his description of the Ottoman Empire in the mid-19th century – has more recently been applied at different times over the past decade and a half to Germany, Italy, Portugal, Greece and France. But this fascination with the crisis country of the moment has masked a broader phenomenon: the erosion of Europeans’ faith in the animating principles that have driven so much of what they have accomplished internally.

The prolonged economic crisis has created centrifugal forces that are pulling European public opinion apart, separating the French from the Germans and the Germans from everyone else. The southern nations of Spain, Italy and Greece are becoming ever more estranged as evidenced by their frustration with Brussels, Berlin and the perceived unfairness of the economic system.

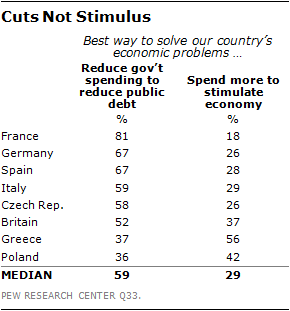

These negative sentiments are driven, in part, by the public’s generally glum mood about economic conditions and could well turn around if the European economy picks up. But Europe’s economic fortunes have worsened in the past year, and prospects for a rapid turnaround remain elusive. The International Monetary Fund expects the European Union economy to not grow at all in 2013 and to still be performing below its pre-crisis average in 2018. Nevertheless, despite the vocal political debate about austerity, a clear majority in five of eight countries surveyed still think the best way to solve their country’s economic problems is to cut government spending, not spend more money.

These are among the key findings of a new study by the Pew Research Center conducted in eight European Union nations among 7,646 respondents from March 2 to March 27, 2013.

A Dyspeptic France

No European country is becoming more dispirited and disillusioned faster than France. In just the past year, the public mood has soured dramatically across the board. The French are negative about the economy, with 91% saying it is doing badly, up 10 percentage points since 2012. They are negative about their leadership: 67% think President Francois Hollande is doing a lousy job handling the challenges posed by the economic crisis, a criticism of the president that is 24 points worse than that of his predecessor, Nicolas Sarkozy. The French are also beginning to doubt their commitment to the European project, with 77% believing European economic integration has made things worse for France, an increase of 14 points since last year. And 58% now have a bad impression of the European Union as an institution, up 18 points from 2012.

Even more dramatically, French attitudes have sharply diverged from German public opinion on a range of issues since the beginning of the euro crisis. Differences in opinion across the Rhine have long existed. But the French public mood is now looking less like that in Germany and more like that in the southern peripheral nations of Spain, Italy and Greece.

Positive assessment of the economy in France have fallen by more than half since before the crisis and is now comparable to that in the south. The French share similar worries about inflation and unemployment with the Spanish, the Italians and the Greeks at levels of concern not held by the Germans. Only the Greeks and Italians have less belief in the benefits of economic union than do the French. The French now have less faith in the European Union as an institution than do the Italians or the Spanish. And the French, like their southern European compatriots, have lost confidence in their elected leader.

Disillusionment with Elected Leaders

Compounding their doubts about the Brussels-based European Union, Europeans are losing faith in the capacity of their own national leaders to cope with the economy’s woes. In most countries surveyed, fewer people today than a year ago think their national executive is doing a good job dealing with the euro crisis. This includes just 25% of the public in Italy, where the sitting Prime Minister Mario Monti was voted out while this survey was being conducted. Even the Germans, who overwhelmingly back their Chancellor Angela Merkel, are slightly more judgmental of her handling of Europe’s economic challenges than they were last year. And Merkel faces the voters in an election in September 2013.

Compounding their doubts about the Brussels-based European Union, Europeans are losing faith in the capacity of their own national leaders to cope with the economy’s woes. In most countries surveyed, fewer people today than a year ago think their national executive is doing a good job dealing with the euro crisis. This includes just 25% of the public in Italy, where the sitting Prime Minister Mario Monti was voted out while this survey was being conducted. Even the Germans, who overwhelmingly back their Chancellor Angela Merkel, are slightly more judgmental of her handling of Europe’s economic challenges than they were last year. And Merkel faces the voters in an election in September 2013.

Nevertheless, Merkel remains the most popular leader in Europe, by a wide margin. She enjoys majority approval for her handling of the European economic crisis in five of the eight nations surveyed. But in Greece (88%) and Spain (57%), majorities now say she has done a bad job, as do half (50%) of those surveyed in Italy.

Economic Gloom

Most Europeans are profoundly concerned about the state of their economies. Just 1% of the Greeks, 3% of the Italians, 4% of the Spanish and 9% of the French think economic conditions are good. Only the Germans (75%) are pleased with their economy.

Most Europeans are profoundly concerned about the state of their economies. Just 1% of the Greeks, 3% of the Italians, 4% of the Spanish and 9% of the French think economic conditions are good. Only the Germans (75%) are pleased with their economy.

And the economic mood has worsened appreciably since before the euro crisis began. Positive sentiment is down 61 percentage points in Spain, 54 points in Britain, 22 points in Italy and 21 points in both the Czech Republic and France.

But despair about the economy may have bottomed out in some nations since 2012. Sentiment seems to have stabilized in the Czech Republic and Poland. And the mood can’t get much worse in Spain, Italy and Greece.

Most Europeans are almost as gloomy about the future. Just 11% of the French, 14% of the Greeks and Poles, and 15% of the Czechs think that their national economic situation will improve over the next 12 months.

A median of 78% in the eight countries surveyed say a lack of jobs is a very big problem in their country. And a median of 71% cite the public debt. Except in Germany, overwhelming majorities in many countries say unemployment, the public debt, rising prices and the gap between the rich and the poor are very important problems. Unemployment is the number one worry in seven of the eight countries. Inequality is the principle concern in Germany.

A median of 78% in the eight countries surveyed say a lack of jobs is a very big problem in their country. And a median of 71% cite the public debt. Except in Germany, overwhelming majorities in many countries say unemployment, the public debt, rising prices and the gap between the rich and the poor are very important problems. Unemployment is the number one worry in seven of the eight countries. Inequality is the principle concern in Germany.

Apprehension about economic mobility and inequality is also widespread. Across the eight nations polled, a median of 66%, including 90% of the French, think children today will be worse off financially than their parents when they grow up. A median of 77% believe that the economic system generally favors the wealthy. This includes 95% of the Greeks, 89% of the Spanish and 86% of the Italians. A median of 60% think the gap between the rich and the poor is a very big problem; that sentiment is felt by 84% of the Greeks and 75% of both the Italians and the Spanish. And a median of 85% say such inequality has increased in the past five years, a concern particularly prevalent among the Spanish (90%).

Apprehension about economic mobility and inequality is also widespread. Across the eight nations polled, a median of 66%, including 90% of the French, think children today will be worse off financially than their parents when they grow up. A median of 77% believe that the economic system generally favors the wealthy. This includes 95% of the Greeks, 89% of the Spanish and 86% of the Italians. A median of 60% think the gap between the rich and the poor is a very big problem; that sentiment is felt by 84% of the Greeks and 75% of both the Italians and the Spanish. And a median of 85% say such inequality has increased in the past five years, a concern particularly prevalent among the Spanish (90%).

Absolute economic deprivation has long been less of an issue in Europe than in some other countries, thanks to the relatively robust European social safety net. But in the wake of economic hard times, deprivation in France is on the rise, where roughly one-in-five say they could not afford food, health care or clothing at some point in the past year.

The Southern Challenge

The euro crisis has created a southern challenge for the European Union. Spain, Italy and Greece have suffered greatly during the economic downturn. And the public mood in these countries is extremely bleak in both absolute and relative terms.

More than seven-in-ten Spanish (79%) and Greeks (72%) say economic conditions are very bad. A majority of Italians (58%) say the same. This compares with a median of 28% for the rest of Europe. More than nine-in-ten in Greece (99%), Italy (97%) and Spain (94%) think the lack of employment opportunities is a very big problem (official unemployment in January 2013 was 27.2% in Greece and in March 2013 was 26.7% in Spain and 11.5% in Italy). Fully 94% of Greeks, 84% of Italians and 69% of Spanish complain that inflation also poses a very big challenge. This compares with a median of 58% elsewhere. And roughly seven-in-ten or more in all three countries fault their leader’s handing of the economic crisis.

Such economic gloom has fed disgruntlement with the European Union. In Greece, 78% now believe that economic integration has weakened the Greek economy, a sentiment about their economy shared by 75% of the Italians and 60% of the Spanish. As a result, nearly two-thirds (65%) of Greeks and about half (52%) of the Spanish have an unfavorable view of the EU. This compares with medians of 59% who question integration and 48% who take a critical view of the EU in the other five countries surveyed.

Concern about inequality is widespread throughout Europe, particularly in the south. A view that the economic system generally favors the wealthy is shared by 95% of the Greeks, 89% of the Spanish and 86% of the Italians. Such frustration exceeds the median of 72% in the other five nations surveyed. Similarly, 84% of the Greeks and 75% of the Italians and Spanish say the gap between the rich and the poor is a very big problem. That compares with a median of just 54% of the Europeans surveyed outside the region who hold such critical views.

So What to Do about the Euro Crisis?

When asked which of the economic challenges facing their countries their government should address first, people in seven of the eight nations choose the lack of employment opportunities. A median of 57% first want their elected leaders to create more jobs. And employment is a particular priority in Spain (72%), Italy (64%) and the Czech Republic (64%).

Europeans are of two minds about public debt, which has been at the center of the debate over the euro crisis since it began. A majority in six of the eight countries surveyed consider debt a very big problem. When pressed to choose between reducing public expenditures and more spending, most publics choose the former, even in Spain (67%) and Italy (59%), despite the fact that people there have already experienced cutbacks in government spending, economic contraction and record high unemployment. Across Europe a median of 59% believe that reducing public debt is the best way to solve their country’s economic problems. But a median of only 17% think debt reduction should be their government’s number one economic priority.

Europeans are of two minds about public debt, which has been at the center of the debate over the euro crisis since it began. A majority in six of the eight countries surveyed consider debt a very big problem. When pressed to choose between reducing public expenditures and more spending, most publics choose the former, even in Spain (67%) and Italy (59%), despite the fact that people there have already experienced cutbacks in government spending, economic contraction and record high unemployment. Across Europe a median of 59% believe that reducing public debt is the best way to solve their country’s economic problems. But a median of only 17% think debt reduction should be their government’s number one economic priority.

Some Good News

Despite rising disillusionment with the European project, the euro, the common currency for 17 of the 27 European Union members, remains in public favor. More than six-in-ten people want to keep the euro as their currency in Greece (69%), Spain (67%), Germany (66%), Italy (64%) and France (63%). And support for the euro has actually increased in Italy and Spain since last year.

Moreover, notwithstanding the fact that only 26% of the British public think being a member of the European Union has been good for their economy and just 43% hold positive views of the European Union, the British, who will hold a referendum on continued EU membership in 2017, remain evenly divided on leaving the EU: 46% say stay and 46% say go.

Moreover, notwithstanding the fact that only 26% of the British public think being a member of the European Union has been good for their economy and just 43% hold positive views of the European Union, the British, who will hold a referendum on continued EU membership in 2017, remain evenly divided on leaving the EU: 46% say stay and 46% say go.

Differences Abound

Overall, the 2013 survey highlights more starkly than ever the differences between the views of Germans and other Europeans on a range of issues. And it underscores that, in some cases, those differences are growing. Germans feel better than others about the economy (by 66 points over the EU median), about their personal finances (by 26 points), about the future (by 12 points), about the European Union (by 17 points), about European economic integration (by 28 points) and about their own elected leadership (by 48 points).

And the survey contradicts oft-repeated narratives about the Germans: that they are paranoid about inflation, disinclined to bail out their fellow Europeans and debt-obsessed. To the contrary, Germans are among the least likely of those surveyed to see inflation as a very big problem and the most likely among the richer European nations to be willing to provide financial assistance to other European Union countries that have major financial problems. And while Germans are worried about public debt, they are more concerned about inequality and equally concerned about unemployment.

And the survey contradicts oft-repeated narratives about the Germans: that they are paranoid about inflation, disinclined to bail out their fellow Europeans and debt-obsessed. To the contrary, Germans are among the least likely of those surveyed to see inflation as a very big problem and the most likely among the richer European nations to be willing to provide financial assistance to other European Union countries that have major financial problems. And while Germans are worried about public debt, they are more concerned about inequality and equally concerned about unemployment.

The prominent role Germans have played in Europe’s response to the euro crisis has evoked decidedly mixed emotions from their fellow Europeans. In every country except Greece, people consider Germans the most trustworthy. At the same time, in six of the eight nations surveyed, people see the Germans as the least compassionate. And in five of the eight, they are considered the most arrogant. In the wake of the strict austerity measures imposed in Greece, Greek enmity toward the Germans knows little bound. Greeks consider the Germans to be the least trustworthy, the most arrogant and the least compassionate. But the Greeks themselves do not fare that well. They are considered the least trustworthy by the French, the Germans and the Czechs.

Slideshow

Slideshow Country Coverage

Country Coverage Interactive Feature

Interactive Feature