As their country struggles with ongoing economic challenges and drug violence, Mexicans are unhappy with national conditions. Roughly eight-in-ten (79%) are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country and 75% say the economy is in bad shape.

As their country struggles with ongoing economic challenges and drug violence, Mexicans are unhappy with national conditions. Roughly eight-in-ten (79%) are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country and 75% say the economy is in bad shape.

Since President Felipe Calderón took office in December 2006, more than 25,000 people have been killed in drug-related violence. However, Mexicans overwhelmingly continue to endorse Calderón’s campaign against the drug cartels. Most also believe the Mexican military is making progress in the drug war, although they are less likely to hold this view now than was the case one year ago.

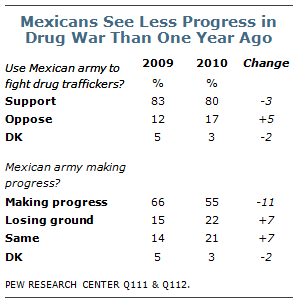

Fully 80% of Mexicans support using the army to fight drug traffickers, essentially unchanged from 83% in 2009. Opposition to using the army has increased only slightly, from 12% to 17%.

Just over half (55%) of Mexicans say the army is making progress against the traffickers, while only 22% think it is losing ground and 21% believe things are about the same as they have been in the past. However, assessments have become somewhat less positive since last year, when 66% felt the army was making progress and only 15% said it was losing ground.

Majorities in Central (60%), North (56%) and South (56%) Mexico believe the army is making progress, while residents of Mexico City (45%) are somewhat less likely to offer a positive assessment.

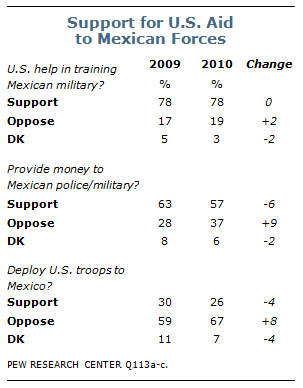

A survey of Mexico by the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, conducted April 14-May 6, also finds continuing support for American involvement in the battle against drug cartels – at least in terms of training and financial support.1 Fully 78% favor the U.S. providing training to Mexican police and military personnel, unchanged from the 2009 poll.

A survey of Mexico by the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, conducted April 14-May 6, also finds continuing support for American involvement in the battle against drug cartels – at least in terms of training and financial support.1 Fully 78% favor the U.S. providing training to Mexican police and military personnel, unchanged from the 2009 poll.

A smaller majority (57%) favors the U.S. providing money and weapons to Mexican police and military personnel, down slightly from 63% last year. Meanwhile, the share of the public that opposes this idea has grown from 28% to 37%. Opposition to the deployment of U.S. troops in Mexico has also increased, from an already high 59% last year to 67% in the current survey.

Support for American assistance to Mexican forces tends to be strongest in North Mexico, parts of which have been especially hard hit by drug-related violence. For example, 67% of those in the North favor the U.S. providing money and weapons to Mexico’s military and police, compared with 56% in the South, 53% in the Central region, and 52% among residents of Mexico City.

The results from the poll also highlight the extent to which Mexican views of the U.S. generally turned negative following passage of the recent Arizona immigration law. Prior to the law’s enactment, 62% of Mexicans had a positive opinion of the U.S., compared with 44% after the law. However, the Arizona controversy had a lesser impact on views about U.S.-Mexican cooperation in the drug war. Still, those surveyed after the law’s passage were slightly more likely than those surveyed before to oppose U.S. training of Mexican police and military forces (16% before the law, 24% after the law).

When asked which country is mostly to blame for their country’s drug violence, 27% name the U.S., while 14% say Mexico, and 51% say both nations are to blame. These results are almost identical to those registered in 2009, when 25% blamed the U.S., 15% blamed Mexico, and 51% said both.

Survey Methods

Results for the survey are based on face-to-face interviews conducted April 14 to April 20, 2010 and May 1 to May 6, 2010. The survey in Mexico is part of the larger 2010 Pew Global Attitudes survey conducted in 22 nations from April 7 to May 8, 2010, under the direction of Princeton Survey Research Associates International. (For more results from the 22-nation 2010 poll, see “Obama More Popular Abroad Than At Home, Global Image Of U.S. Continues To Benefit” released June 17, 2010.)

The table provides details about the survey’s methodology, including the margin of sampling error based on all interviews conducted in Mexico. For the results based on the full sample, one can say with 95% confidence that the error attributable to sampling and other random effects is plus or minus the margin of error. In addition to sampling error, one should bear in mind that question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of opinion polls.

The table provides details about the survey’s methodology, including the margin of sampling error based on all interviews conducted in Mexico. For the results based on the full sample, one can say with 95% confidence that the error attributable to sampling and other random effects is plus or minus the margin of error. In addition to sampling error, one should bear in mind that question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of opinion polls.