In addition to the topics discussed above, the survey included questions about a variety of other issues, including how people think others around the world perceive their nation; which countries are considered the top providers of international aid and disaster relief; attitudes regarding isolationism and international engagement; views on the use of military force; Russian perceptions about threats to their country; and finally, international opinions about who will win the World Cup.

Is Your Country Popular Abroad?

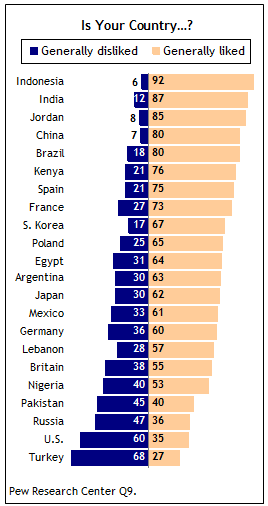

When asked how their country is viewed abroad, majorities in 18 of 22 nations say their country is generally liked. Indonesians are the most likely to think their country is well-regarded – roughly nine-in-ten (92%) say Indonesia is generally liked by people in other nations, although at least 80% say their country is popular in India (87%), Jordan (85%), China (80%) and Brazil (80%).

When asked how their country is viewed abroad, majorities in 18 of 22 nations say their country is generally liked. Indonesians are the most likely to think their country is well-regarded – roughly nine-in-ten (92%) say Indonesia is generally liked by people in other nations, although at least 80% say their country is popular in India (87%), Jordan (85%), China (80%) and Brazil (80%).

However, while America’s overall image may have improved around the world over the last two years, most Americans think their country is unpopular. Six-in-ten Americans say the U.S. is generally disliked by people in other countries, while just 35% say is it generally liked. Among the 22 nations surveyed, only Turks (27%) are less likely than Americans to think their country enjoys international popularity. Still, Americans are more likely to think their country is popular abroad now than they were in 2005, when just 26% held this view.

Aside from the U.S. and Turkey, the only other nations where less than a majority thinks their country is generally liked are Russia (36%) and Pakistan (40%). Pakistanis are much less likely to believe their country is popular now than in 2005, when 53% held this view.

Aid and Disaster Relief

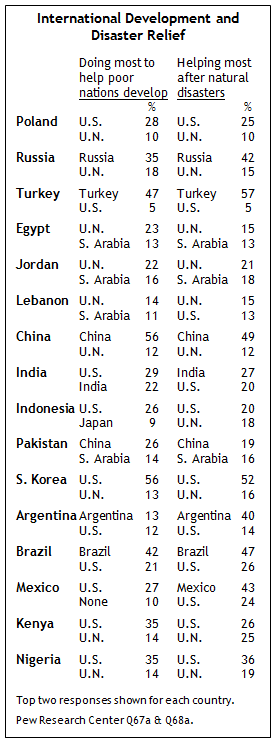

Substantial numbers in many countries identify the U.S. as a global leader both in promoting international development and helping nations recover from natural disasters.

Substantial numbers in many countries identify the U.S. as a global leader both in promoting international development and helping nations recover from natural disasters.

When asked which country is doing the most to help poor nations develop, more in seven of the 16 nations where this question was asked name the U.S. than any other country. And the U.S. is the second-most-named in another three nations.

However, responses to this question are diffuse and it is clear that there is no general consensus on this issue. For instance, even though the U.S. is the top pick in seven countries, South Korea is the only nation in which a majority names the U.S.

Publics in these 16 countries express fairly similar views on the issue of how nations respond to natural disasters. When asked which country does the most to help countries that have experienced natural disasters, people in five nations choose the U.S. more than any other country, while the U.S. is the second- most-cited in another six. Again, responses are diffuse, and South Korea is the only country in which a majority identifies the U.S.

Aside from South Korea, the U.S. receives relatively high marks both for its development aid and its disaster relief efforts in several other countries where its overall favorability ratings are high, such as Poland, Nigeria and Kenya.

The U.S. is also the top pick for disaster relief in Indonesia, where it provided considerable aid following the December 2004 tsunami, although the U.S. garners only 20% of the total. In Pakistan, where the U.S., among others, provided aid following an October 2005 earthquake and where it continues to give large amounts of both military and development aid today, few name the U.S. as their top choice. Only 13% of Pakistanis think the U.S. is doing the most to help poor nations develop and 12% say it does the most to help after natural disasters.

Even though these questions asked which country does the most to help poor nations develop and which country does the most following disasters, respondents in many nations name the United Nations. For instance, it is the top pick for both development aid and disaster relief in all three Arab nations surveyed: Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon.

There is also a tendency in many places for respondents to name their own country. Russians, Turks, Chinese, Argentines, and Brazilians all think their countries are leaders both in providing development aid to poor countries and in helping after natural calamities. Meanwhile, Indians and Mexicans name their nations as the leaders for disaster relief.

Views on International Engagement

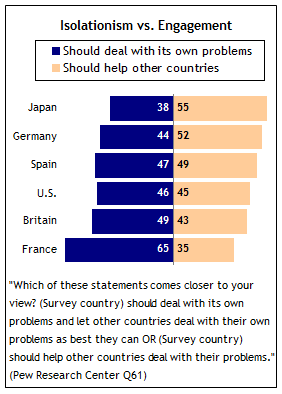

The U.S. is often portrayed as being isolationist, but this survey suggests that Americans are not that different from citizens of other developed nations on this issue. Americans – along with the Germans, Spanish, and British – are roughly divided over how much their country should help other nations.

The U.S. is often portrayed as being isolationist, but this survey suggests that Americans are not that different from citizens of other developed nations on this issue. Americans – along with the Germans, Spanish, and British – are roughly divided over how much their country should help other nations.

In the U.S., 46% say their country should focus on its own problems, while 45% believe it should help other countries deal with their problems. By a slim 52%-44% margin, Germans lean slightly towards helping other nations. The Spanish are almost evenly divided on this issue, while the British lean slightly toward a more isolationist position.

Among the nations where this question was asked, the outliers are Japan and France. Japanese respondents are the most internationalist: 55% say they should help other countries, while only 38% believe Japan should deal with its own problems. The French emerge as the most isolationist public – nearly two-thirds (65%) say their country should focus on issues at home, while only 35% believe it should assist other nations.

Military Force Is Sometimes Necessary

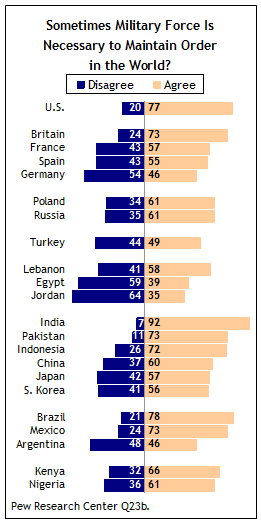

Among the countries surveyed, a consensus exists on the use of military force: In 17 of 22 countries, a majority agrees that “It is sometimes necessary to use military force to maintain order in the world.”

Among the countries surveyed, a consensus exists on the use of military force: In 17 of 22 countries, a majority agrees that “It is sometimes necessary to use military force to maintain order in the world.”

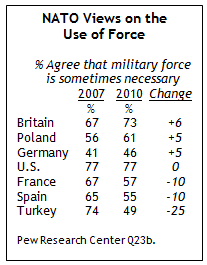

Majorities in five of the seven NATO member states surveyed support the use of military force to maintain world order. This perspective is especially common in the U.S., where 77% say military force is sometimes needed, unchanged from 2007 when this question was last asked.

Fully 73% hold the same view in Britain, up from 67% in 2007. The share of Poles who think force can be necessary has also increased slightly, from 56% to 61%.

Trends have moved in the opposite direction, however, in France and Spain. While majorities in these two nations continue to say military action can be necessary to ensure stability, the share of the public expressing this view has dropped by 10 percentage points in both countries.

Less than a majority say force is sometimes necessary in Germany (46%) and Turkey (49%). Only three years ago, roughly three-in-four Turks (74%) said military force is sometimes required to maintain order.

Less than a majority say force is sometimes necessary in Germany (46%) and Turkey (49%). Only three years ago, roughly three-in-four Turks (74%) said military force is sometimes required to maintain order.

Elsewhere, majorities in Jordan (64%) and Egypt (59%) disagree with the notion that military means should sometimes be used for the sake of global stability. A majority in Lebanon (58%) embraces the use of such means to ensure world order.

In Asia, majorities consistently agree that force can be necessary. This is especially true in India (92%), although most in Pakistan (73%), Indonesia (72%), China (60%) and Japan (57%) also agree with this position. In South Korea, more now (56%) hold this view than did so in 2007 (43%).

In Africa, more than six-in-ten in Kenya (66%) and Nigeria (61%) currently agree with the need for a military approach at times, while roughly three-quarters did so in both countries in 2007 (Kenya 75%, Nigeria 74%).

Threats to Russia

Many Russians believe their country faces serious threats from abroad. Moreover, Russians are concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism, both in their country and in the world.

Many Russians believe their country faces serious threats from abroad. Moreover, Russians are concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism, both in their country and in the world.

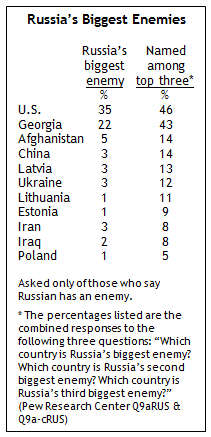

More than half of Russians (57%) believe there are countries that are enemies of Russia. When those who perceive such threats were asked to name the states they consider to be antagonists, a plurality points to the U.S. (35%), while 22% name Georgia. Far smaller proportions name Afghanistan (5%) or states that border Russia – Latvia (3%), Ukraine (3%), China (3%), Lithuania (1%) and Estonia (1%). Only 3% of Russians name Iran while 2% say Iraq.

Russians who say their country has enemies were also given the opportunity to name the nation’s second and third biggest threats. Looking across all three mentions, the U.S. and Georgia were again cited most often.

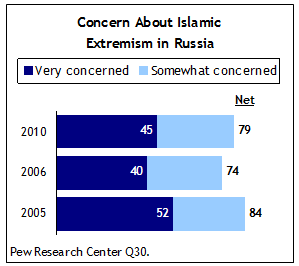

A large majority of Russians are concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism in their country (79%) and the world (78%). And Russians’ concern about the rise in Islamic extremism is intense; 45% say they are very worried about such activities in both Russia and the world.

A large majority of Russians are concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism in their country (79%) and the world (78%). And Russians’ concern about the rise in Islamic extremism is intense; 45% say they are very worried about such activities in both Russia and the world.

Concern about the rise of extremist violence is particularly common in Central Russia, a region recently touched by extremist violence. This survey, conducted less than two months after the bombings of the Moscow Metro in March 2010, finds that 93% of people living in Central Russia say they are very or somewhat concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism in their country. Fewer Russians living in the South (69%) hold the same view. Similar regional patterns of concern also exist about the rise of Islamic extremism in the world.

Anxiety about the threat of extremism has changed somewhat in the last several years. In 2005, not long after the September 2004 terrorist attack on a school in Beslan, Russia, 84% of Russians expressed concern about the rise of Islamic extremism in their country; 52% were very concerned. In 2006, such anxiety dipped somewhat; at that time, 74% of Russians expressed worry about the rise of Islamic extremism in Russia.

The 2010 World Cup

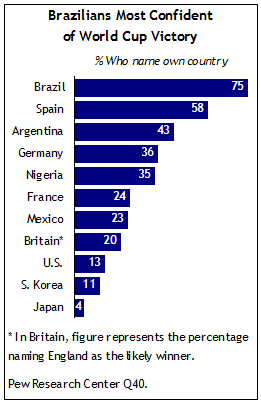

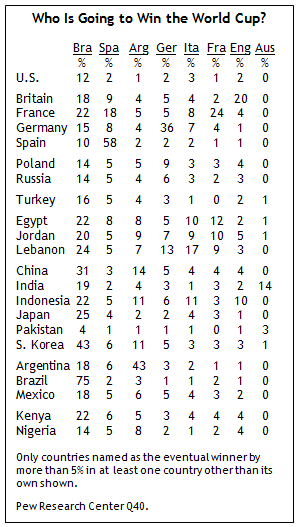

Brazilians express more confidence in their country’s chances to win the World Cup than do publics in any other country surveyed with a team in the tournament; three-quarters in that country say five-time champion Brazil will once again prevail. Confidence is also high in Spain, where a majority (58%) expects their country, which has never won a World Cup, to emerge victorious this year.

Brazilians express more confidence in their country’s chances to win the World Cup than do publics in any other country surveyed with a team in the tournament; three-quarters in that country say five-time champion Brazil will once again prevail. Confidence is also high in Spain, where a majority (58%) expects their country, which has never won a World Cup, to emerge victorious this year.

Confidence is low in Japan, where just 4% think their country will win the World Cup. South Koreans, who co-hosted the 2002 World Cup with Japan, also have low expectations for their team, as do Americans; only 11% and 13%, respectively, name their own countries when asked who will win this year’s tournament.

Japan and South Korea are the only World Cup participants surveyed where more name a team other than their own as the eventual winner; in both, Brazil is the most often named country.

In the 11 countries surveyed that are not participating in the soccer competition, more also name Brazil as this year’s likely winner than name any other team. This view is especially common in China, where about three-in-ten (31%) say the soccer powerhouse will win the World Cup; the second-most-named country, Argentina, is mentioned by 14% of Chinese.

The survey, which was conducted prior to the start of the World Cup, finds that, despite low expectations about their team’s chances, South Koreans were among the most excited about the tournament. About eight-in-ten (79%) said they were looking forward to the World Cup. This level of enthusiasm about the 2010 World Cup, the first-ever to be held in the African continent, was matched only in Nigeria (79%). About seven-in-ten (71%) Kenyans also expressed excitement. Americans were among the least enthusiastic; 27% said they were excited about the World Cup, while 68% said they were not.

The survey, which was conducted prior to the start of the World Cup, finds that, despite low expectations about their team’s chances, South Koreans were among the most excited about the tournament. About eight-in-ten (79%) said they were looking forward to the World Cup. This level of enthusiasm about the 2010 World Cup, the first-ever to be held in the African continent, was matched only in Nigeria (79%). About seven-in-ten (71%) Kenyans also expressed excitement. Americans were among the least enthusiastic; 27% said they were excited about the World Cup, while 68% said they were not.