One year after the global economy descended into recession, publics worldwide remain dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country and with their nation’s economic conditions. Many publics are even more discontented than they were in 2008, notably in Britain, Germany, Spain, Poland and Russia. China and India are exceptions to these trends; in both nations most are content with their country’s direction and current economic situation.

Even with continued and increasingly negative views of current conditions, optimism for the economy in the coming year is relatively widespread and more common than one year ago.

Dissatisfaction with Country Direction

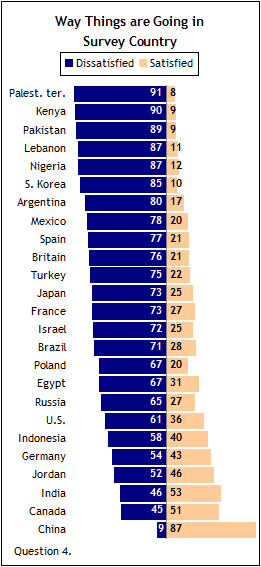

Majorities in 22 of 25 countries surveyed worldwide are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country. Dissatisfaction is pervasive among some publics – the Palestinian territories (91%), Kenya (90%), Pakistan (89%), Lebanon (87%), Nigeria (87%) and South Korea (85%).

Majorities in 22 of 25 countries surveyed worldwide are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country. Dissatisfaction is pervasive among some publics – the Palestinian territories (91%), Kenya (90%), Pakistan (89%), Lebanon (87%), Nigeria (87%) and South Korea (85%).

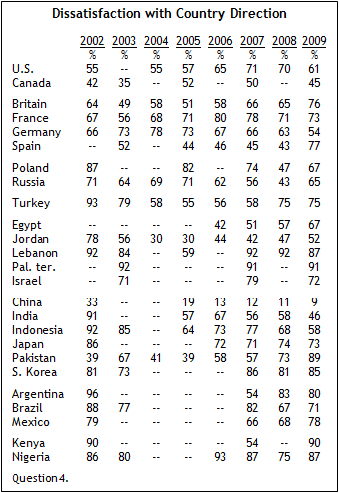

Dissatisfaction with the general direction of one’s country is consistent with past Pew Global Attitudes findings; trend data show that dissatisfaction typically dominates the public mood in most countries.

In the past year, however, dissatisfaction has swelled dramatically in several countries. Most notably, while 43% of Spaniards held downbeat views of their country’s general conditions in 2008, more than three-quarters (77%) do so in 2009, a 34-point increase in the proportion of the population holding gloomy views of their country’s direction.

Substantial increases in dissatisfaction also are apparent in Russia (+22 percentage points) and Poland (+20 points); just under half of both publics were unhappy with their country’s situation in 2008, while about two-thirds are now.

Similarly, since last measured in Kenya in 2007, discontent with the country’s direction has grown from 54% to 90%.

Similarly, since last measured in Kenya in 2007, discontent with the country’s direction has grown from 54% to 90%.

Contrary to this generally negative view about national conditions, the vast majority of Chinese (87%), as well as majorities in India (53%) and Canada (51%), are satisfied with their country’s direction.

The public mood is more upbeat in 5 of the 21 countries for which there are trends. Improvements in public sentiment occurred in both India and Indonesia; 58% of Indians felt discontented in 2008 whereas only 46% do now. Discontent in Indonesia fell from 68% to 58% during the same period.

More modest decreases in disaffection levels are evident in the U.S., Germany and Lebanon. Seven-in-ten in the U.S. held negative views of their country’s direction in 2008, while just over six-in-ten (61%) do now. Similarly, in Germany, 63% felt downbeat about their country’s situation last year while just over half (54%) do so today.

Continued and Growing Concern for National Economy

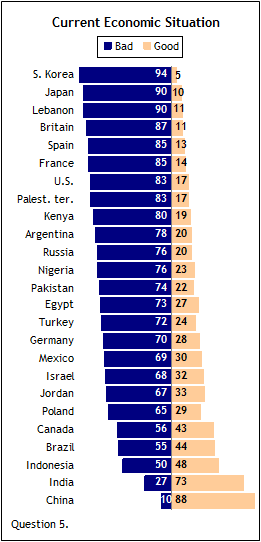

As in 2008, most publics are not only dissatisfied with their country’s direction, but are also concerned about their national economy: In all but three countries in the current survey, majorities now say that their national economic conditions are bad.

As in 2008, most publics are not only dissatisfied with their country’s direction, but are also concerned about their national economy: In all but three countries in the current survey, majorities now say that their national economic conditions are bad.

In 12 countries, 75% or more say that their current national economic situation is bad. No publics are more negative than South Korea (94% bad), Lebanon (90%) and Japan (90%), where roughly nine-in-ten say their country’s economy is bad. Many Western Europeans are only slightly less downbeat about the state of their economies; more than eight-in-ten British (87%), Spanish (85%), and French (85%) feel their economies are in rough shape. Americans are not far behind, with 83% viewing their economy negatively.

Exceptions exist to these glum assessments of economic conditions, albeit only a few. Those who view their economic conditions as positive tend to live in countries that continue to experience economic growth amidst the recent global economic crisis. For example, in China, which has continued to enjoy positive growth rates over the past year, an overwhelming majority (88%) have positive views of their national economic situation. Likewise, in India, another country with a positive growth rate, 73% say their national economic situation is good.

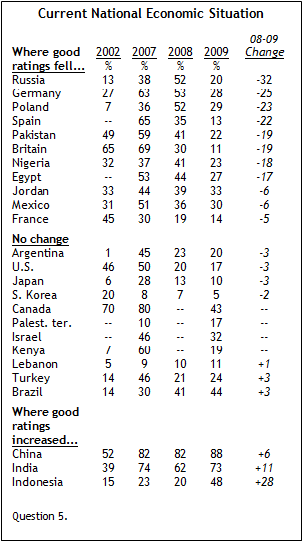

Publics have grown increasingly bearish about the national economy since 2007. And in the past year alone, significantly fewer people say that their national economic conditions are somewhat or very good in 10 of the 21 countries surveyed where trends exist.

In several cases, the declines are substantial. In Russia, where oil and gas revenues have fueled economic growth throughout much of this decade, ratings have turned sharply negative in the last year. Only 20% of Russians say their economy is good, whereas 52% held this view last year.

Smaller but still substantial decreases in upbeat opinion about economic realities are evident in a number of European Union countries. About half in Germany (53%) and Poland (52%) expressed rosy views of their national economies in 2008; currently, just 28% of Germans and 29% of Poles see their country’s economy as good. For the Spanish and British, public sentiment about the economy has hit new lows; roughly one-third in Spain (35%) and Britain (30%) were positive in 2008, compared with just over one-in-ten in each country this year. Positive ratings in France have dropped from an already low 19% to 14% today.

Smaller but still substantial decreases in upbeat opinion about economic realities are evident in a number of European Union countries. About half in Germany (53%) and Poland (52%) expressed rosy views of their national economies in 2008; currently, just 28% of Germans and 29% of Poles see their country’s economy as good. For the Spanish and British, public sentiment about the economy has hit new lows; roughly one-third in Spain (35%) and Britain (30%) were positive in 2008, compared with just over one-in-ten in each country this year. Positive ratings in France have dropped from an already low 19% to 14% today.

While rare, increases in positive views of one’s national economy have occurred. In 2008, just 20% of Indonesians held positive views of the national economy; currently, nearly half do (48%). In India and China, the increases are far more modest, though they rise from a much higher base reflecting the generally positive trends of the past few years. The share of the Indian public holding a positive view of the economy has increased from 62% in 2008 to 73% in 2009. As for China, 82% held a bright view of their economy in 2008 while 88% do now.

Measured but Increased Optimism for Short-Term Economic Future

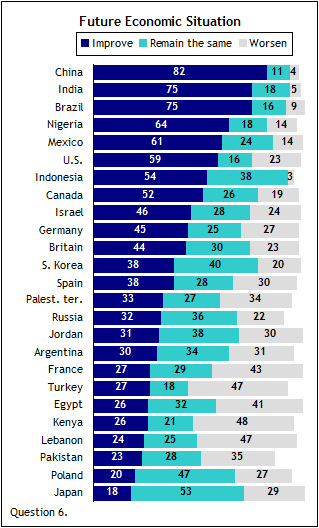

While negative views about current national economic conditions dominate in most publics, and are more common than in 2008, optimism for the near-term economic future somewhat outpaces pessimism. In 12 countries, majorities or pluralities think their nation’s economy will improve over the next year. In seven countries, pluralities say the economy will worsen, and in six countries the most common response is that it will remain the same.

While negative views about current national economic conditions dominate in most publics, and are more common than in 2008, optimism for the near-term economic future somewhat outpaces pessimism. In 12 countries, majorities or pluralities think their nation’s economy will improve over the next year. In seven countries, pluralities say the economy will worsen, and in six countries the most common response is that it will remain the same.

Large majorities in the fast-growing economies of China (82%), India (75%) and Brazil (75%) say that they expect economic conditions in their country to improve a lot or a little in the next 12 months. Not only is optimism widespread in these countries, but it is strong; substantial percentages in each say their economies will improve a lot (China 24%, India 22%, Brazil 38%). Few in these countries expect that conditions will worsen (China 4%, India 5%, Brazil 9%).

Smaller majorities in Nigeria (64%), Mexico (61%), the U.S. (59%), Indonesia (54%) and Canada (52%) also feel that their national economic futures look brighter. Many in Nigeria (22%) and Mexico (19%) are convinced the economy will improve a lot.

While in no country does a majority hold a negative view of the near-term economic future, a number of publics are far less optimistic. Only about one-quarter in Egypt (26%), Kenya (26%) and Lebanon (24%), and one-fifth of those in Poland (20%) and Japan (18%) expect good things for their national economic future.

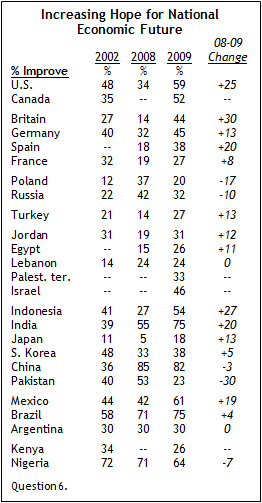

While public optimism about the economic future is measured, hopeful views are more common than they were a year ago. In 14 countries, more now say that the economy will improve in the next 12 months.

While public optimism about the economic future is measured, hopeful views are more common than they were a year ago. In 14 countries, more now say that the economy will improve in the next 12 months.

Optimism has surged, in particular, in Britain; in 2008, only 14% of Britons voiced hope for the economic future, while 44% do so in the current survey. In fact, promising views of the economic future have grown in all of the Western European countries surveyed, including Spain (+20 points), Germany (+13) and France (+8). In the U.S., bright views of the economic future also are more common; at the outset of the global economic crisis in 2008, only 34% of Americans voiced a positive opinion about the financial future, while nearly six-in-ten (59%) hold out buoyant expectations now.

While being generally economically pessimistic, even the Muslim-majority publics of Turkey (+13 points), Jordan (+12) and Egypt (+11) express more hope for their financial futures than just one year ago. The Lebanese, however, are equally as negative this year as last.

Except among Pakistanis, views are more positive in Asia as well; hopes for a bright economic future are far more common now than one year ago in Indonesia (+27 points) and India (+20). Even in Japan, a country that often ranks as one of the most economically negative, upbeat expectations are more common; while only a handful (5%) of Japanese surveyed in 2008 offered a rosy view of the economic future, nearly one-in-five (18%) Japanese do now. On the other hand, Pakistani views have soured; in 2008, a majority held out bright expectations for the economic future while only 23% do now. In China, there continues to be widespread optimism about the economy over the next 12 months; 82% expect the economy to improve, little changed from 2008 (85%).

In Poland and Russia, and to some extent in Nigeria, opinions about the economic short-term are more downbeat: in 2009, fewer Poles (-17 points), Russians (-10) and Nigerians (-7) say the economy will get better in the next 12 months than did in 2008.

Less Optimism for Children’s Future

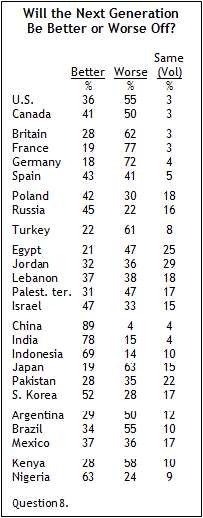

Overall, views about the long-term prospects for the next generation are slightly more negative than positive in the current survey. In 15 countries, majorities or pluralities feel that when their children grow up, they will be worse off than people are now. Majorities or pluralities in 10 countries say that their children will be better off.

Overall, views about the long-term prospects for the next generation are slightly more negative than positive in the current survey. In 15 countries, majorities or pluralities feel that when their children grow up, they will be worse off than people are now. Majorities or pluralities in 10 countries say that their children will be better off.

Pessimism about the prospects for the next generation is common across the developed countries surveyed, and especially prevalent in France and Germany. Roughly three-quarters of the French (77%) and Germans (72%) are downbeat about the prospects for their children’s futures. Just over six-in-ten among the Japanese (63%) and British (62%), and 55% in the U.S. and 50% in Canada, are gloomy about their children’s prospects. The Spanish are equally split between holding out hope for their children’s futures (43%) and not (41%).

Views are mixed in Turkey and the Middle East. The Turks are decidedly pessimistic; six-in-ten (61%) feel that the future will be worse for their children. Nearly half of Egyptians (47%) and Palestinians (47%) say that their children will be worse off. Opinions are more divided in Jordan and Lebanon; 36% of Jordanians and 38% of Lebanese feel that their children will be worse off, though nearly equal percentages are hopeful that things will be better for them (Lebanon 38%, Jordan 32%,). The Israelis offer a more upbeat view; nearly half of Israelis (47%) trust that the future will hold better things for their children.

A majority of Kenyans (58%) say that their children will be worse off. By contrast, most Nigerians (63%) hold out hope that their children’s lives will be better than their own.

Despite a great deal of dissatisfaction with the general state of their country and economy, as well as limited optimism for the coming 12 months, Poles and Russians lean towards holding out hope for their children. More than four-in-ten in Russia (45%) and Poland (42%) say that their children’s lives will be better, while 22% of Russians and 30% of Poles say they will be worse.

Optimistic views are not universal but predominate in Asia. Large majorities of adults in China (89%), India (78%) and Indonesia (69%) as well as a majority in South Korea (52%) trust their children will have better lives than they themselves do. Pakistanis are more pessimistic (35%) than optimistic (28%) about their children’s lives, while the Japanese are decidedly negative; six-in-ten (63%) in Japan feel that their children’s lives will be worse.

Optimistic views are not universal but predominate in Asia. Large majorities of adults in China (89%), India (78%) and Indonesia (69%) as well as a majority in South Korea (52%) trust their children will have better lives than they themselves do. Pakistanis are more pessimistic (35%) than optimistic (28%) about their children’s lives, while the Japanese are decidedly negative; six-in-ten (63%) in Japan feel that their children’s lives will be worse.

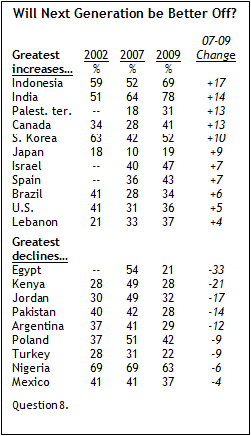

Views about children’s economic futures have changed a good deal in the past year. Optimism is significantly more widespread in 11 countries and less common in nine. Indonesians (+17 points), Indians (+14), Palestinians (+13), Canadians (+13) and South Koreans (+10) are somewhat more likely in 2009 than in 2008 to trust in a bright future for their children.

On the other hand, Egyptians are far less likely to believe the future holds something positive for their children; in 2008, about half (54%) of Egyptians felt that their children’s lives would be better than their own, while in 2009 only 21% feel this way. A less sizeable, but still substantial drop, occurred in hopeful views in Kenya and Jordan in the same time frame; half of both Kenyans (49%) and Jordanians (49%) felt that their children would be better off than themselves in 2008, but one year later roughly three-in-ten in both countries hold onto such a bright view. Smaller drops in positive views occurred in Pakistan (-14 points), Argentina (-12), Poland (-9) and Turkey (-9).

Chart

Chart