Next year, China will no longer be the most populous country in the world, ceding the title to India, according to projections by the United Nations. China has had the largest population in the world since at least 1950, when the UN started keeping records. But it is now projected to experience an absolute decline in its population beginning as early as 2023.

This Pew Research Center analysis is primarily based on the World Population Prospects 2022 report by the United Nations. The estimates produced by the UN are based on “all available sources of data on population size and levels of fertility, mortality and international migration” and do not include the areas separately listed by the UN as “China, Hong Kong SAR”; “China, Macau SAR”; or “China, Taiwan Province of China.”

Because future levels of fertility and mortality are inherently uncertain, the UN uses probabilistic methods to account for both the past experiences of a given country and the past experience of other countries under similar conditions. The medium scenario projection is the median of many thousands of simulations. The low and high scenarios make different assumptions about fertility: In the high scenario, total fertility is 0.5 births above the total fertility in the medium scenario; in the low scenario, it is 0.5 births below the medium scenario.

Other sources of information for this analysis are available through the links included in the text.

Here are key facts about China’s population and its projected changes in the coming decades, based on data from the UN and other sources:

Although China will lose its title as the world’s most populous country, the UN still estimates its population at 1.426 billion people in 2022. This is larger than the entire population of Europe (744 million) and the Americas (1.04 billion). It’s also roughly equivalent to the population of all the nations in Africa (1.427 billion).

Related: Global population projected to exceed 8 billion in 2022; half live in just seven countries

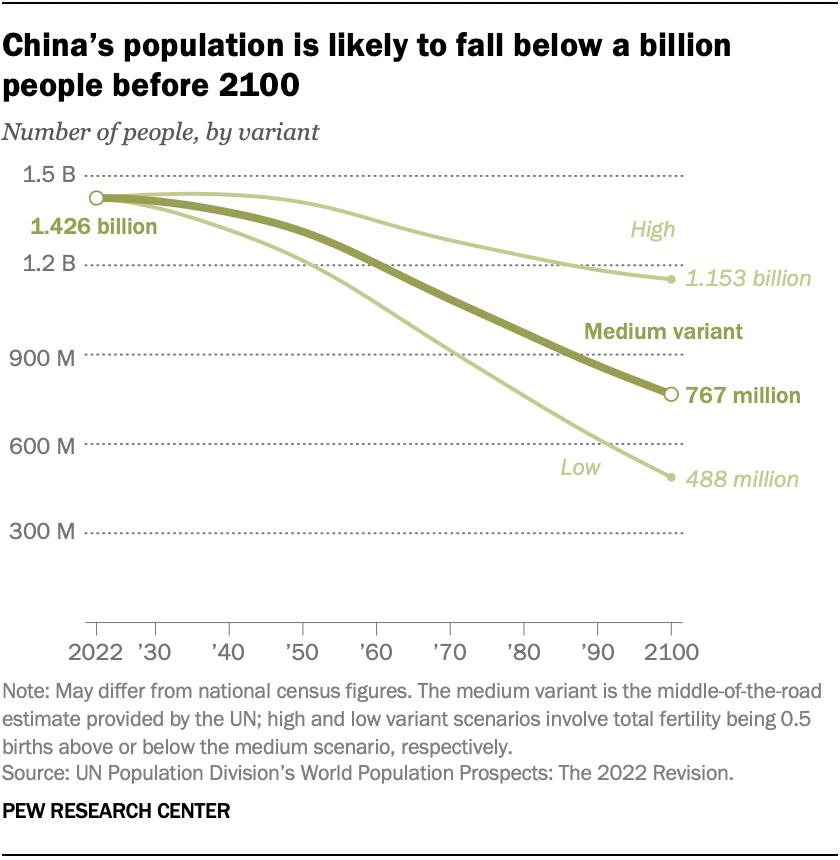

The UN forecasts that China’s population will decline from 1.426 billion this year to 1.313 billion by 2050 and below 800 million by 2100. That’s according to the UN’s “medium variant,” or middle-of-the-road projection. The large population decline is projected even though it assumes that China’s total fertility rate will rise from 1.18 children per woman in 2022 to 1.48 in 2100.

Using the UN’s “high variant” scenario – in which the total fertility rate in China is projected to be 0.5 births per woman above that of the medium variant scenario – the country’s population is still projected to fall to 1.153 billion by 2100. And in the UN’s “low variant” scenario – where the total fertility rate is projected to be 0.5 births below that of the medium variant scenario – China’s population is projected to fall to as low as 488 million by 2100.

For comparison purposes, the U.S. population of 337 million in 2021 is expected to grow to 394 million by 2100 in the UN’s medium variant scenario. The UN’s high variant scenario projects a population of 543 million Americans by then, while in its low scenario, the U.S. population would shrink to 281 million.

Other groups and academics differ somewhat from the UN in their forecasts of China’s population, but nearly all still predict a decline. Some demographers, for example, think the country’s population might have already peaked in 2021 or even earlier. These other estimates sometimes rely less on official Chinese population data (which researchers say is inflated because of financial incentives for local governments) and instead use other data, such as the number of mandatory vaccines administered to newborns in China. Still, regardless of the precise timing of China’s population peak or the magnitude of its projected decline, there is near-universal consensus that the nation’s population is on a trajectory of decline.

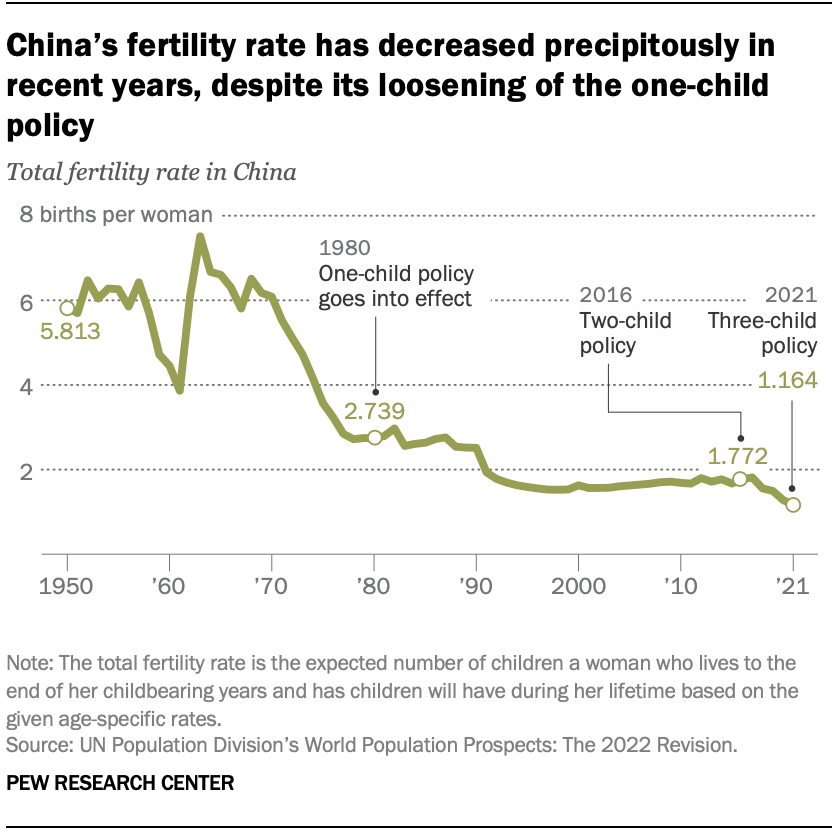

China’s 2022 total fertility rate is estimated to be 1.18 children per woman – down substantially from earlier decades and significantly below the “replacement rate” of 2.1 children per woman. This is despite the relaxation of the country’s well-known one-child policy, which was introduced in 1980 but amended to allow two children beginning in 2016 and three children beginning in 2021.

Notably, fertility rates in China were already falling prior to the introduction of the one-child policy, as they often fall alongside economic development and urbanization. And aside from a brief one-year increase following the allowance of a second child, fertility rates have continued to fall in China.

The YuWa Population Research Institute, a Beijing-based think tank, has concluded that China is among the most expensive places to raise a child and that these economic concerns – rather than governmental policies – are tied to women not wanting to have more children these days.

In addition to having fewer children overall, women in China are choosing to have children later in life. Since 2000, the mean childbearing age in China has increased by three years, rising from 26 to 29. By comparison, the mean childbearing age has gone up by just one year across all middle-income countries (which China is part of).

The mean age of first marriage has increased alongside the childbearing age in China. Based on data from China’s 2020 census, the mean age of first marriage for women in 2020 was 28, up from 24 in 2010. Some have cited China’s zero-COVID policy as a contributing factor to delayed motherhood.

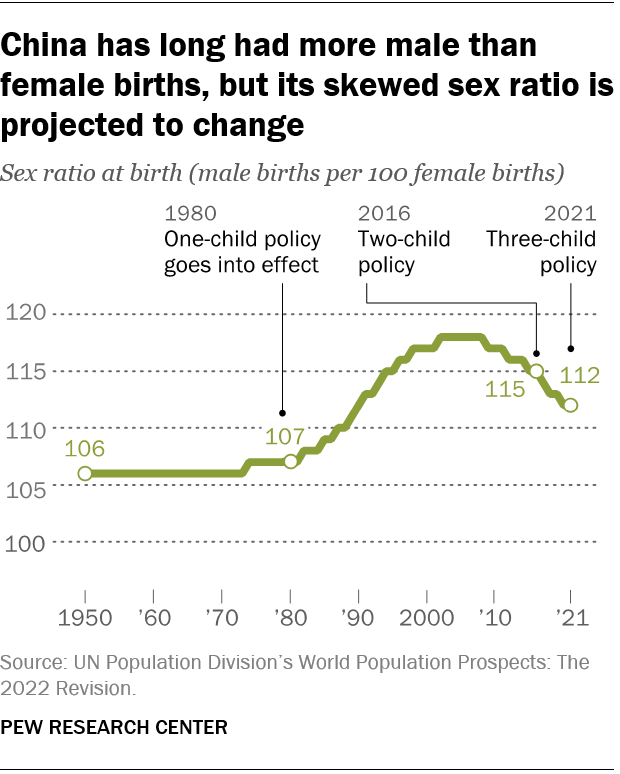

China is among the countries with the most skewed sex ratio at birth, according to a recent Pew Research Center study of UN data. In fact, China accounted for 51% of the world’s “missing” females between 1970 and 2020, due to sex-selective abortion or neglect, according to a 2020 UN report.

While China continues to have a skewed sex ratio at birth – 112 male births per 100 female births, as of 2021 – this is down slightly from a high of 118 male births per 100 female births between 2002 and 2008. Still, as of 2021, China had a huge overall sex imbalance of around 30 million more men than women. China also has among the highest abortion rates per 1,000 women ages 15 to 49 of any country, according to estimates from the Guttmacher Institute.

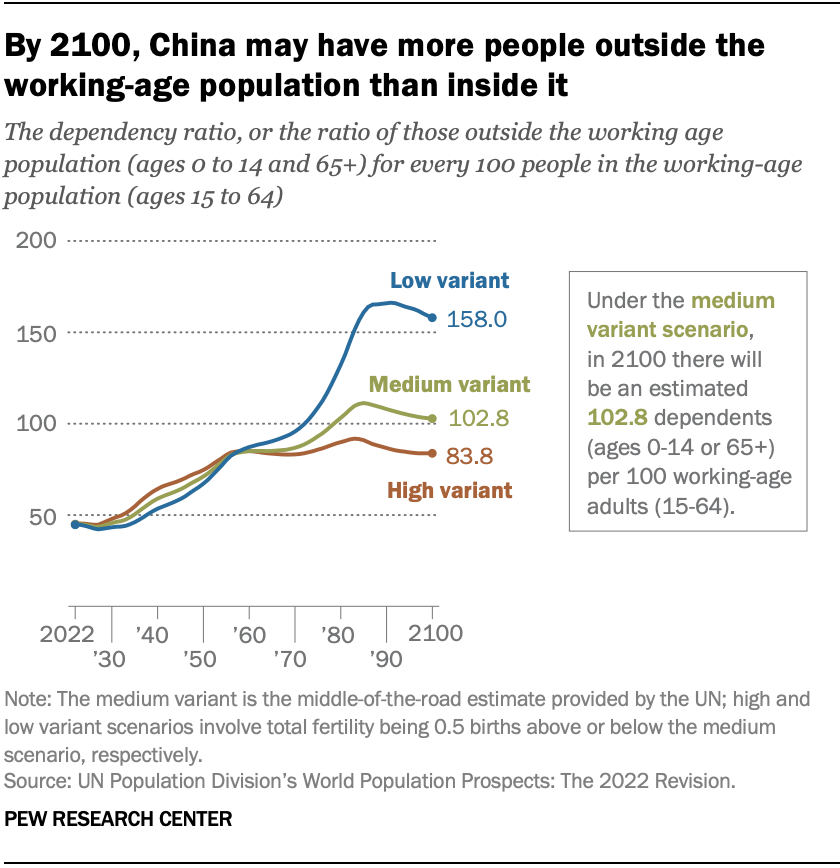

China has a rapidly aging population. According to Chinese state media, China is already approaching a “moderately aging” scenario, in which 20% of its population is ages 60 and older. By 2035, that percentage is expected to rise to 30%, or more than 400 million people.

By 2100, China also appears poised to roughly double its “dependency ratio” – the proportion of its population that is outside working age (either ages 0 to 14 or ages 65 and older), compared with the proportion that is working age (15 to 64). This is even true in the UN’s “low variant” projection. In fact, based on the UN’s middle-of-the-road estimate, there will be more Chinese people outside the working-age population than in it – a dependency ratio of 101.1 – by the year 2079.

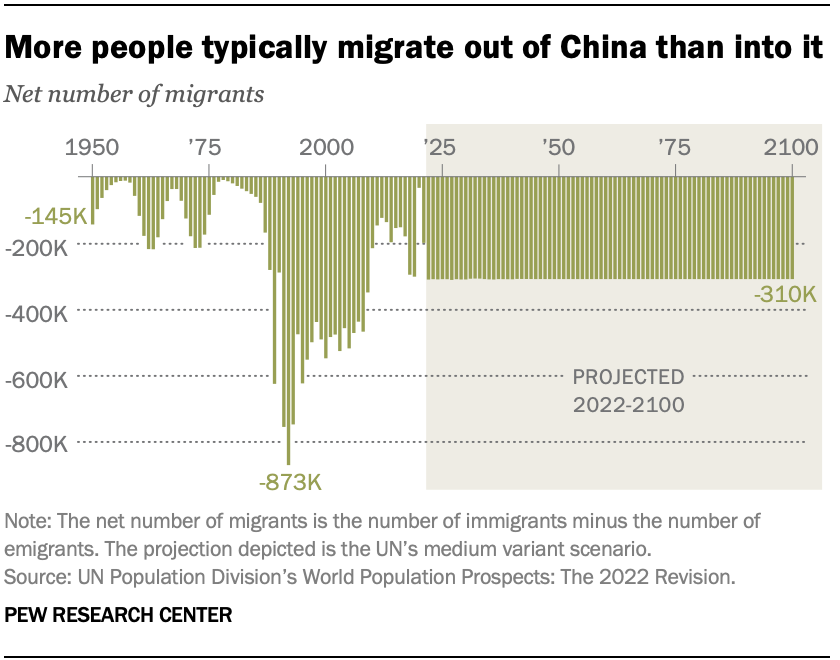

More people migrate out of China per year than into it, further decreasing the population. Since at least 1950, when the UN began compiling statistics, China has had a net negative number of migrants – meaning more people are leaving the country than arriving. In 2021, for example, the country experienced an estimated net out-migration of 200,000 people. Still, this is down from a higher point in the early 1990s, when around 750,000 or more people per year were leaving China. As part of its medium variant projections, the UN forecasts that China will continue to experience net negative migration through at least 2100, with estimates hovering around 310,000 people leaving the country per year.

CORRECTION (Dec. 15, 2022): A previous version of the chart “China has long had more male than female births, but its skewed sex ratio is projected to change” misplaced the line indicating the start of China’s two-child policy in 2016. The chart has been replaced. This change does not substantively affect the findings of this report.