Dozens of world leaders are convening virtually this week to join President Joe Biden at the Leaders Summit on Climate. In a recent Pew Research Center survey, 44% of Americans said dealing with climate change should be a top long-term foreign policy goal for the United States. But Americans’ views about the importance of addressing climate change and other foreign policy priorities differed by a number of factors – most notably their broader attitudes toward international engagement.

In general, Americans who have faith in international cooperation were more likely to prioritize policies that require engaging with global partners, while those who doubt the value of collaborating with other countries prioritized policies that can be pursued independently. And similar divides cut across party affiliation, education and community type, according to the survey of 2,596 U.S. adults conducted Feb. 1-7.

Overall, the American public is closely divided on the question of how much international engagement benefits the nation. A slight majority (54%) said many of the nation’s problems can be solved by working with other countries, while a narrow minority (45%) said few of the country’s problems can be solved through international cooperation. And these differences of opinion over international engagement often extend to specific issues.

This analysis examines Americans’ views of foreign policy priorities and demographic patterns that are present across policies asked. For this study, we surveyed 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses and survey methodology.

‘Outward’ vs. ‘inward’ foreign policy goals

One way to analyze Americans’ views of foreign policy priorities is to think of each issue as either “outward” or “inward” in nature, as some international relations experts have done using the framework of “internationalism” and “isolationism.” While no issue fits exclusively into one category or the other, prioritizing outward issues – such as preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction – tends to reflect liberal internationalism, a school of thought that promotes countries working together for mutual benefit. Prioritizing inward issues – such as protecting the jobs of American workers – generally reflects an emphasis on domestic priorities that do not necessarily involve international cooperation. Some scholars have pointed to former President Donald Trump’s “America First” foreign policy agenda as an example of these kinds of priorities.

The Center’s recent survey finds notable differences in views of specific issues depending on how Americans feel about international cooperation more broadly. For example, those who doubt the benefits of international cooperation were far more likely to say that curbing immigration – both illegal and legal – should be a top foreign policy priority for the nation. By contrast, those who express more faith in international cooperation were far more likely to prioritize combating climate change, strengthening the United Nations, promoting democracy abroad and aiding refugees. Only when it comes to containing North Korean power did equal shares of the two groups give top priority.

These patterns are generally consistent across the foreign policy priorities asked, but there is one notable outlier. Those who value international cooperation were more likely than those who don’t to favor limiting the power and influence of Russia – a goal that, on its face at least, could be described as more inward- than outward-facing.

Some of this could be due to partisan divides in views of Russia: Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are more likely than Republicans and GOP leaners to see limiting Russian power as a top priority. This reflects an established pattern in previous Pew Research Center surveys. In this most recent survey, Democrats were also more likely than Republicans to lack confidence in Russian President Vladimir Putin (87% vs. 78%), and in 2020 they were more likely than Republicans to have an unfavorable view of Russia (78% vs. 68%). Also in 2020, Democrats were much more likely than Republicans to view Russia’s power and influence as a major threat to the U.S. (68% vs. 46%).

Differences by party, education and community type

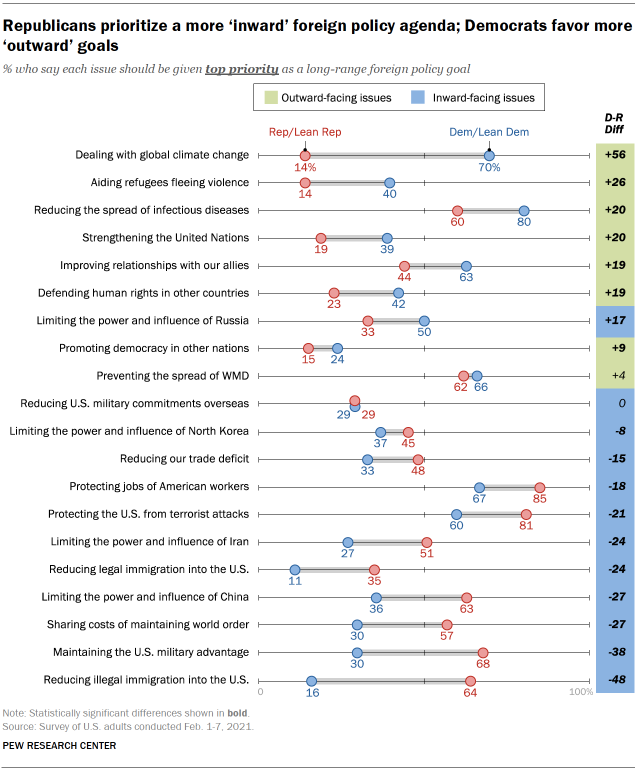

Overall, Democrats were more likely than Republicans to believe that many of the nation’s problems can be solved by working with other countries (71% vs. 33%), the February survey found. Accordingly, they were also more likely than Republicans to prioritize outward-facing foreign policy goals, while Republicans were more likely to prioritize inward goals.

Democrats, for example, were five times as likely as Republicans to think dealing with global climate change should be a top priority (70% vs. 14%, respectively). On the flip side, Republicans were four times as likely as Democrats to see curbing illegal immigration as a critical issue (64% vs. 16%). The only inward-facing foreign policy goal that Democrats prioritized more than Republicans was limiting the power and influence of Russia.

Though there were significant differences between partisans on nearly all of the issues included in the survey, similar shares of Democrats and Republicans did agree that reducing U.S. military commitments abroad and preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction should be top foreign policy goals.

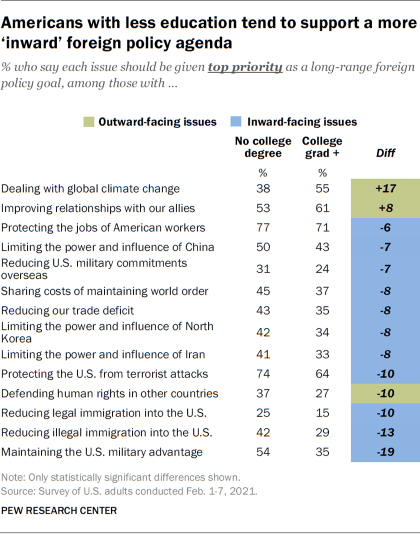

Educational attainment also related to Americans’ attitudes toward specific foreign policies. Those without undergraduate degrees tended to fall on the more insular side, while those who have graduated from college tended to favor a more outward-facing agenda.

These divides were particularly stark in views of national security issues. For example, those with no college degree were more likely to prioritize maintaining the U.S. military’s dominance, while those with more education were more likely to prioritize combating climate change.

This pattern was not consistent across all foreign policy goals, however. Those with more education were less likely to see supporting human rights abroad – a more outward-facing policy goal – as a top priority.

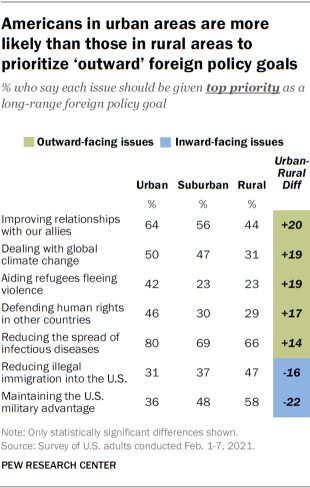

Americans’ community type was also a factor in how they viewed some key foreign policy priorities. In general, those living in urban areas prioritized more outward facing policies, such as dealing with climate change or combating the spread of disease, while those in rural areas prioritized more inward-facing issues, such as reducing illegal immigration.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.