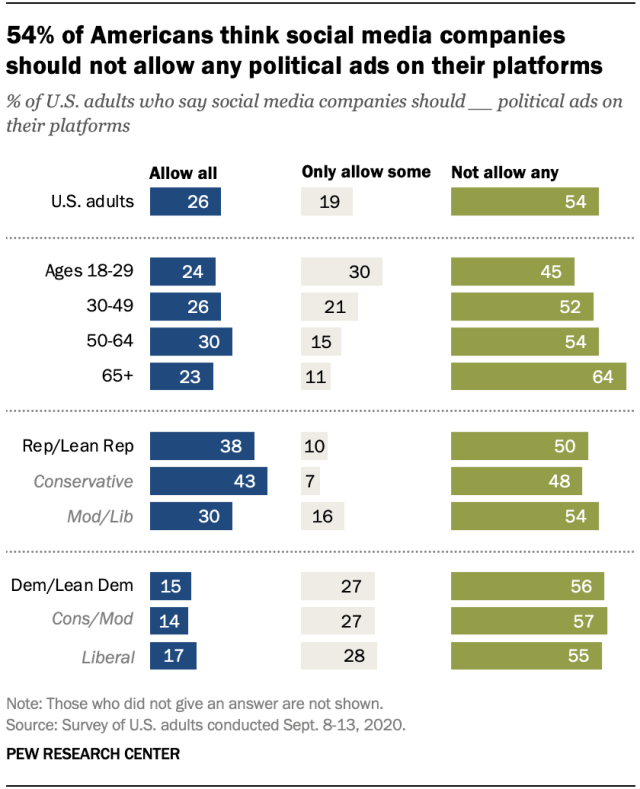

More than half of U.S. adults (54%) say social media companies should not allow any political advertisements on their platforms. And a larger share (77%) finds it not very or not at all acceptable for these companies to use data about their users’ online activities to show them ads from political campaigns, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted Sept. 8-13, 2020.

At the same time, 45% say social media companies should allow at least some political ads on their platforms, with 26% saying these firms should allow all of these ads and 19% backing the idea that only some should be allowed. And 22% think it is at least somewhat acceptable for social media companies to use data about their users’ online activities to show them political campaign ads.

The sentiments against political ads extend across most groups, though there are some differences tied to factors like partisanship and age. For instance, just 15% of Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party say that social media companies should allow all political ads on their platforms, compared with 38% of Republicans and GOP leaners. Some 27% of Democrats say only some political ads should be allowed on these platforms, compared with a much smaller share of Republicans (10%) who say the same. When it comes to not allowing any political ads on these sites at all, 56% of Democrats and half of Republicans express this view.

This is part of a series of posts on Americans’ experiences with and attitudes about the role of social media in politics today. Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand attitudes about political advertisements on social media platforms. To explore this, we surveyed 10,093 U.S. adults from Sept. 8-13, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

Within the Democratic cohort, there are no differences in these views by ideology. However, Republicans are slightly more divided along ideological lines. For instance, 43% of conservative Republicans say social media companies should allow all political ads on their platforms, while 30% of moderate to liberal Republicans say the same. Moderate and liberal Republicans are also about twice as likely as conservative Republicans to say these sites should allow only some political ads (16% vs. 7%).

These views also vary somewhat by age. Those ages 65 and older are most likely to favor not allowing political ads on social media. Some 64% of those 65 and older say these sites should not allow any political ads on their platforms, compared with slightly over half of those ages 30 to 64 and 45% of those 18 to 29. By contrast, those in the youngest age group are more likely to favor allowing only some ads on the site, with 30% holding this view, compared with about one-in-five or fewer of those in older age groups.

There are also differences in these views by race and ethnicity and gender. White Americans (56%) are more likely than Black (47%), Hispanic (51%) and Asian Americans (48%) to say these companies should not allow any political ads on their site. However, White Americans (28%) are also more likely than Black (21%), Hispanic (23%) and Asian American adults (19%) to say social media sites should allow all political ads on their sites. Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans are all more likely to favor social media sites allowing only some political ads on their sites when compared with White adults. Women (58%) are also more likely than men (49%) to say these sites should not allow any political ads on their platforms. Conversely, men are more likely than women to favor allowing all political ads on these sites (31% vs. 21%).

These findings reflect an intensifying dynamic in political debate this election cycle. In recent years, social media sites have emerged as news hubs and serve as online public spheres where people encounter and discuss political information. Yet, in the current campaign season, social media companies and political candidates themselves have drawn criticism for publishing and approving ads bearing false information.

Some companies are reacting. In late 2019, Twitter announced it would ban sponsored political content from the site altogether, and more recently others, like Facebook, revealed their plans to ban any new political ads in the week before the contest.

Tactically, many political advertisements on social media rely on microtargeting – a strategy used to reach a specific group of users based on their geographical location or personal interests. Social media companies have taken a range of approaches when it comes to the moderation of ad targeting. For example, Facebook uses a robust classification system to categorize users’ preferences, including political leanings. On the other hand, Google said in 2019 it would restrict how political candidates can microtarget users with ads based on political attributes.

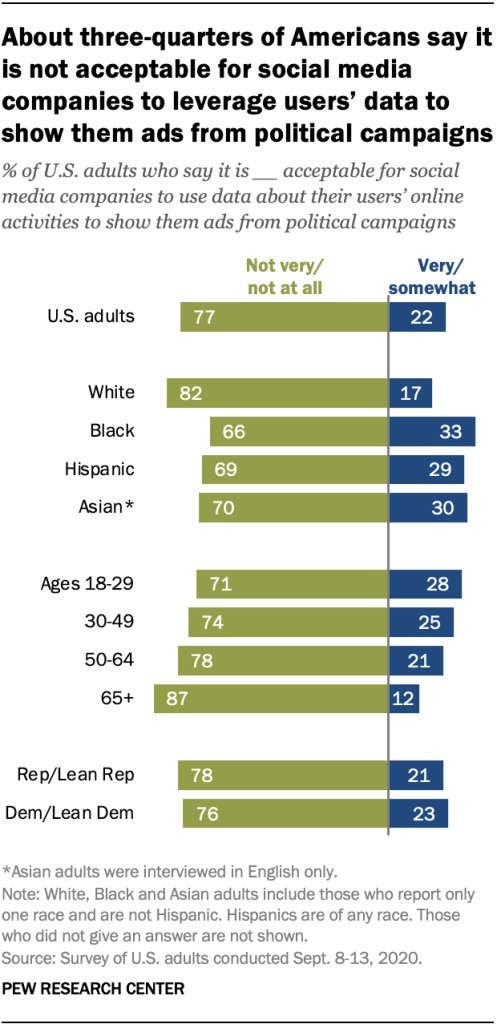

When asked about the acceptability of social media companies using data about their users’ online activities to show them ads from political campaigns, roughly three-quarters of Americans (77%) say this practice is not very or not at all acceptable. Some 53% say this targeting is not acceptable at all. About a fifth (22%) find targeting somewhat or very acceptable, with a small share (4%) saying this is very acceptable.

There are not major differences between partisans on this issue. At the same time, there are differences in these attitudes by race and ethnicity. The vast majority of White adults (82%) find social media companies using data about their users’ online activities to target them with ads from political campaigns to be not very or not at all acceptable, compared with smaller shares – though still majorities – of Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans.

Views of the acceptability of this practice also vary by age. Those 65 and older (87%) are more likely than younger Americans to find this kind of ad targeting not very or not acceptable at all, though seven-in-ten or more of those in younger groups also hold this view.

This public resistance to political ad targeting is not new. These findings line up with a 2018 Center survey that found that roughly six-in-ten U.S. social media users (62%) found it unacceptable for social media sites to use data about them and their online activities to show messages from political campaigns. And the results in the current survey tie to more recent research showing the public is concerned about the interplay of major tech companies and politics. For instance, most Americans think social media sites censor political viewpoints, and few U.S. adults say they are very or somewhat confident in tech companies to prevent misuse of their platforms in the 2020 election.

Note: This is part of a series of blog posts leading up to the 2020 presidential election that explores the role of social media in politics today. Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

CORRECTION (October 2020): The methodology section has been updated to reflect the correct cumulative response rate. None of the study findings or conclusions were affected.

Other posts in this series: