Which kinds of statements do Americans see as acceptable in political debate, and which are out of bounds? How do people view the way President Donald Trump and other elected officials talk about politics? How do they navigate conversations about politics and other sensitive topics with strangers and friends? In conducting a recent major survey about political discourse in the United States, we at Pew Research Center sought to use techniques and experiments to help capture the nuances of how Americans feel about the tenor of debate in the country. Here are some of the ways we went about it.

Using scenarios to make questions feel connected to people’s own lives. We tend to use scenarios selectively in our surveys because they are time-consuming and there often are more direct ways to measure people’s views about a subject.

But we wanted to get people to think about how they might approach a conversation with someone who differs from them politically. So, it made sense to develop a scenario that asked them to imagine such a situation.

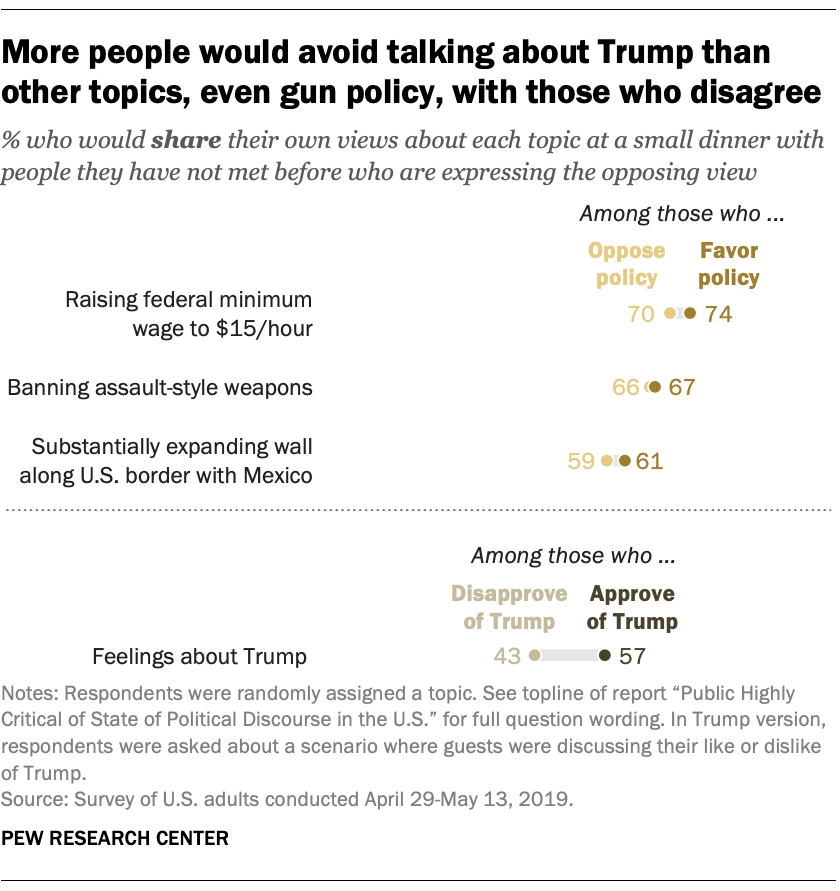

We asked people about their attitudes on several topics in the news – raising the minimum wage, banning assault weapons and expanding the U.S.-Mexico border wall, as well as whether they approve of Trump’s job performance. Later in the survey, we asked them to imagine being at a small dinner with people who took the opposite view from their own on all these topics, including Trump.

This approach proved revealing: People said they would be more comfortable talking about the three other topics than about Trump. And there were, at most, only slight differences in Americans’ willingness to talk about these subjects at a dinner gathering depending on their views on assault weapons and the other topics.

But that was not the case with Trump. Those who disapproved of the way he is handling his job were far less likely than Trump approvers to say they would be willing to share their opinions about him in a social gathering with those who had the opposite view (43% of those who disapproved vs. 57% of those who approved).

Using survey experiments to examine how views about standards of political behavior vary for those on “your team” vs. those on the “other team.” Experiments are useful tools that can help survey researchers understand whether differences in things like question wording and framing elicit different responses.

One experiment in the survey tested the acceptability of a range of political behaviors for elected officials, while another asked about the importance of some behavioral traits. In both of these experiments, respondents were randomly assigned to be asked about generic “elected officials,” “Republican elected officials,” or “Democratic elected officials.”

Within both parties, larger shares expressed a desire for high standards of conduct among officials of the other party than among those in their own party. For example, nearly eight-in-ten Republicans said it was very important for Democratic officials to treat their opponents with respect and be willing to compromise – and about the same share of Democrats said this about Republican officials – but only about half said it was very important for their own party’s officials to act this way.

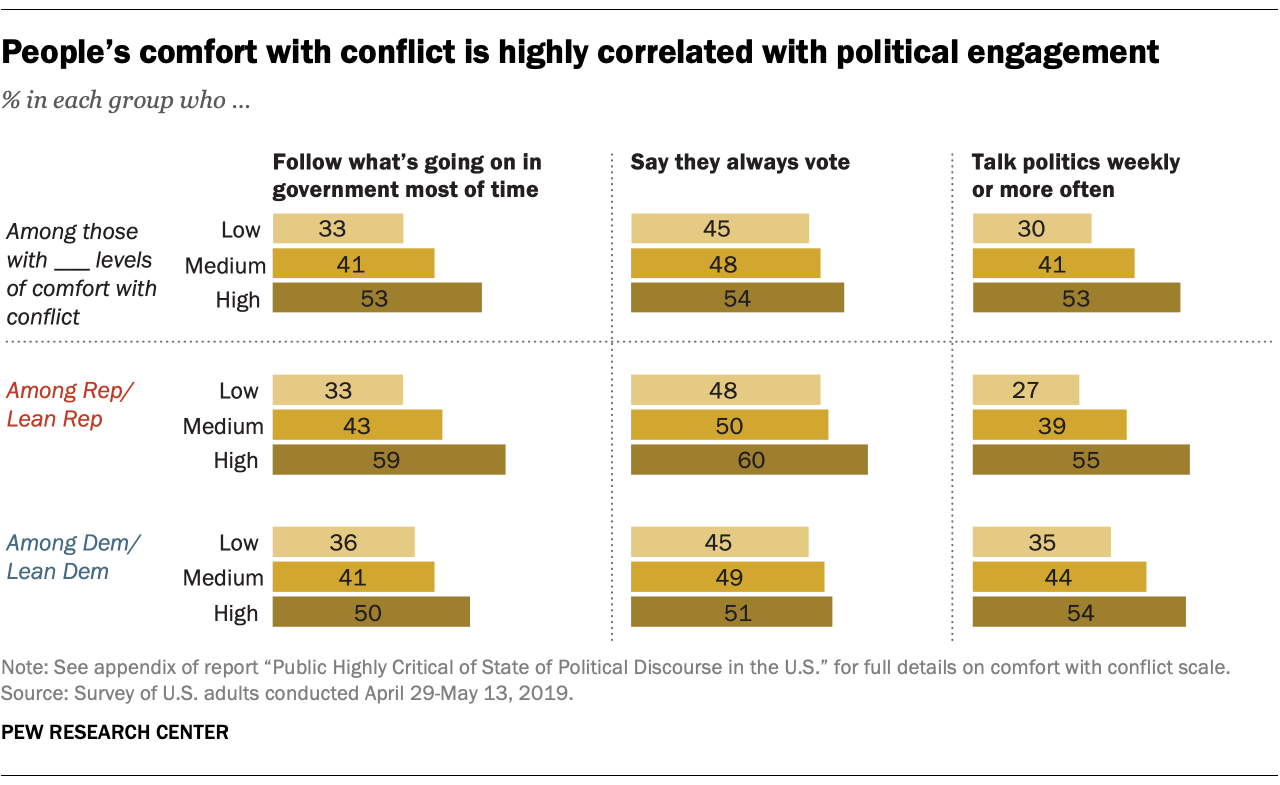

Exploring the relationship between personal comfort with conflict and political interest and engagement. We asked a series of questions designed to measure Americans’ comfort with conflict in their everyday lives (general conflict, not political conflict specifically). This allowed us to look at the relationship between this characteristic and broader views on political discourse.

We found those who are more comfortable with conflict (that is, those who enjoy challenging the opinions of others and say disagreements don’t bother them much) are more attentive to and active in politics.

And while it’s no surprise that more conflict-averse people are less likely to be willing to share their political views in social settings with people who hold different views, the magnitude of some of these gaps was striking. For example, 76% of those with a high level of comfort with conflict said they would share their feelings about Trump in a social situation with people who held opposing views; only 26% of those with a low level of comfort with conflict said the same.

And while it’s no surprise that more conflict-averse people are less likely to be willing to share their political views in social settings with people who hold different views, the magnitude of some of these gaps was striking. For example, 76% of those with a high level of comfort with conflict said they would share their feelings about Trump in a social situation with people who held opposing views; only 26% of those with a low level of comfort with conflict said the same.

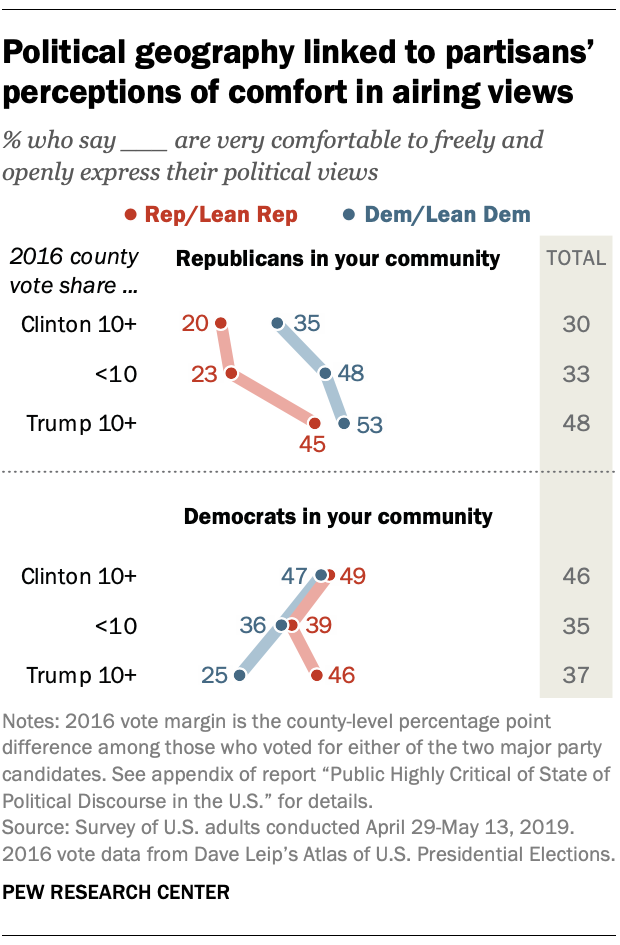

Looking at how perceptions of the climate for political discourse vary by political geography. We also examined how the political makeup of Americans’ home communities is associated with their views on discourse. For example, Republicans in counties Trump carried in the 2016 election by at least 10 percentage points were more likely to say fellow Republicans in their community feel very comfortable expressing their political views than those who live in counties where Trump did not perform as well. (Here are more details on how we classified political geography.)

Looking at how perceptions of the climate for political discourse vary by political geography. We also examined how the political makeup of Americans’ home communities is associated with their views on discourse. For example, Republicans in counties Trump carried in the 2016 election by at least 10 percentage points were more likely to say fellow Republicans in their community feel very comfortable expressing their political views than those who live in counties where Trump did not perform as well. (Here are more details on how we classified political geography.)

Connecting personal values to policy attitudes. Our surveys often connect people’s personal values with their attitudes on other topics. For example, our recent survey on trust and distrust found that people with high levels of interpersonal trust were more likely to express confidence in several groups – including scientists and business leaders – than those with less interpersonal trust.

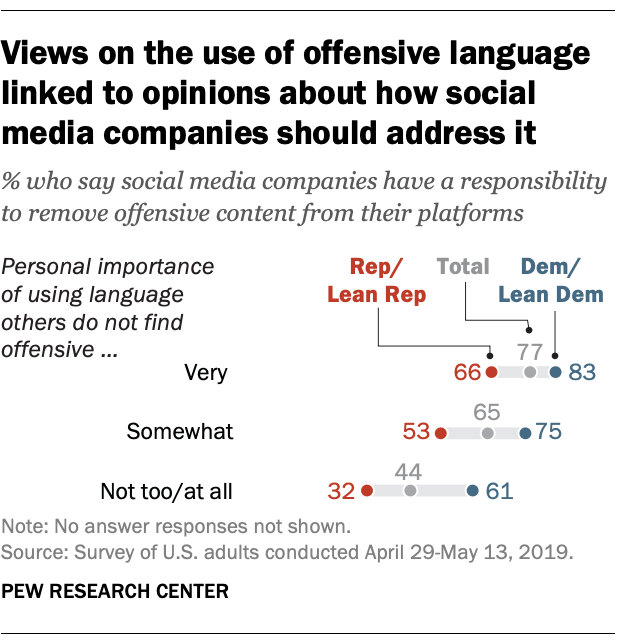

In the survey on political discourse, Americans’ personal views on the importance of avoiding offensive language were closely linked with their opinions about whether social media companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content from their platforms.

In the survey on political discourse, Americans’ personal views on the importance of avoiding offensive language were closely linked with their opinions about whether social media companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content from their platforms.

Among U.S. adults who said it was very important to them not to use language that others find offensive, 77% said social media companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content from their platforms. Among those who attached little or no importance to avoiding offensive language, just 44% said the same.