From the 1980s until relatively recently, most national polling organizations conducted surveys by telephone, relying on live interviewers to call randomly selected Americans across the country. Then came the internet.

It has taken survey researchers some time to adapt to the idea of online surveys, but a quick look at the public polls on an issue like presidential approval reveals a landscape now dominated by online polls rather than phone polls. Pew Research Center itself now conducts the majority of its U.S. polling online, primarily through its American Trends Panel.

The fact that many public opinion surveys today are conducted online is no secret to avid poll watchers. What is not well known, however, is what this migration to online polling means for the country’s trove of data documenting American public opinion over the past four decades, on issues ranging from abortion and immigration to race relations and military interventions. Specifically, can pollsters just add new online results to a long chain of phone survey results, or is this an apples-to-oranges situation that requires us to essentially throw out the historical data and start anew?

The core issue is one of comparability, since research tells us that people sometimes respond to online and phone polls differently. When an actual person, in the form of an interviewer, is involved in asking questions, people are more likely to respond in a way that paints them in a positive light or avoids an uncomfortable interaction. This social dynamic is removed when people are taking surveys on their laptop or smartphone, without an interviewer. The difference in estimates stemming from the method of interviewing is known as a mode effect.

The key question then becomes: If a new online poll estimate differs noticeably from an older phone estimate, does that signal a real change in public opinion, or is the difference just an artifact of the different mode in which the poll was conducted?

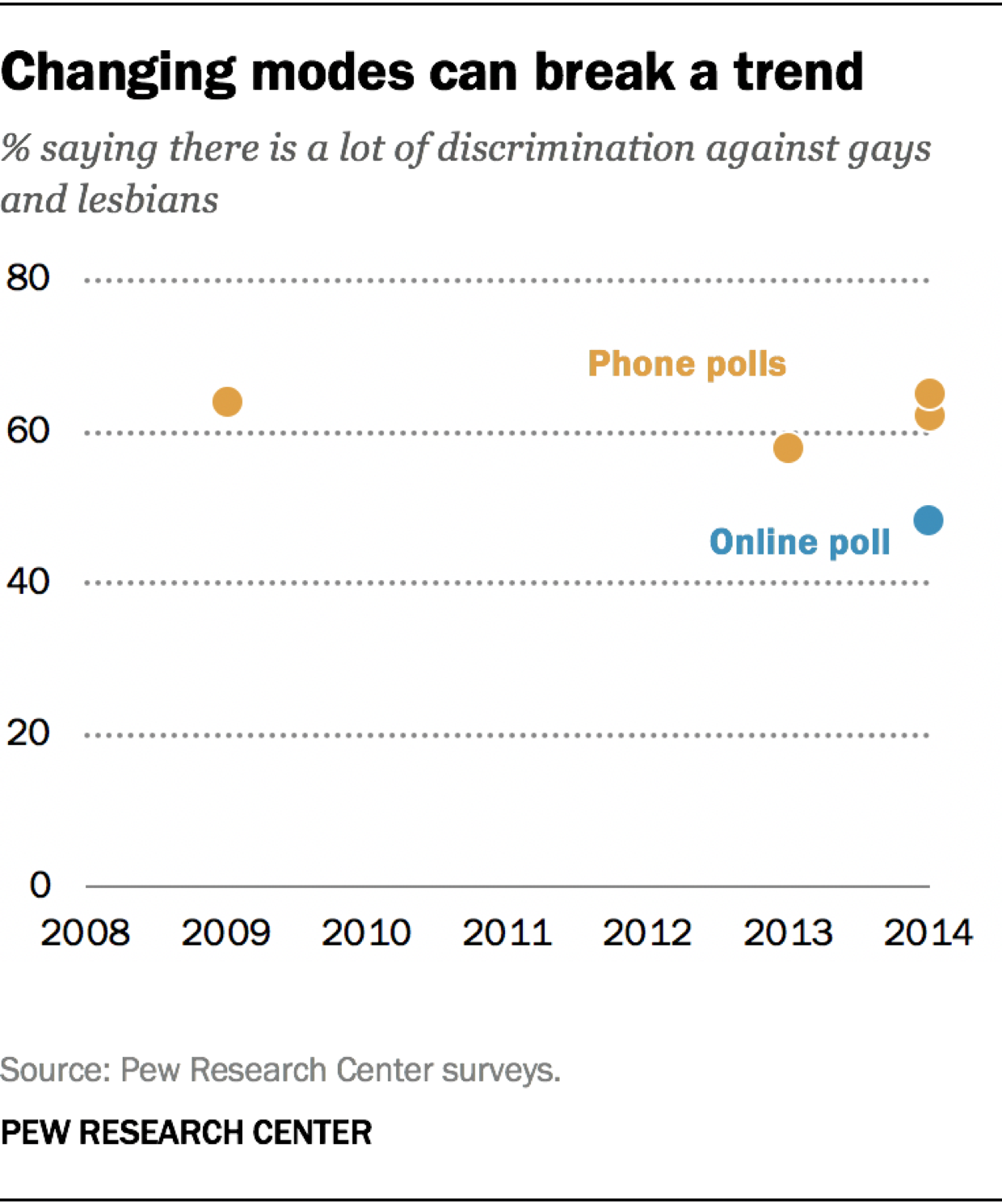

Consider a real example. Between 2009 and 2014, the Center’s phone polls found that the share of Americans saying there was a lot of discrimination against gays and lesbians tended to hover just under two-thirds. Then, in 2014, the Center fielded the same question online and found that just 48% of Americans expressed that same view.

Consider a real example. Between 2009 and 2014, the Center’s phone polls found that the share of Americans saying there was a lot of discrimination against gays and lesbians tended to hover just under two-thirds. Then, in 2014, the Center fielded the same question online and found that just 48% of Americans expressed that same view.

Did that signal a major decline in perceived discrimination against gays and lesbians? No, it reflected a mode effect. Researchers know this because the online poll was part of an experiment in which a random half of the adults were contacted to take the survey online and the other half were interviewed by phone. The phone estimate from the experiment (62%) was similar to the prior phone poll estimates. The experiment revealed that adults were significantly more likely to say that gays and lesbians faced a lot of discrimination when they were speaking with an interviewer than when they recorded their answers privately online. This raises several important additional questions that we’ll answer below.

Are all polling questions susceptible to mode effects?

No. Research finds that the method of interviewing affects some questions but not others. For example, in a 2017 Pew Research Center randomized mode experiment, views on the 2010 health care law passed by Barack Obama and Congress showed no mode difference. The law got a 48% approval rating both online and by phone. Donald Trump’s presidential approval rating was also similar online (44%) and by phone (42%). Other questions in that study, however, did show mode differences. When asked about their personal financial situation, 20% of those polled online admitted to being in poor shape financially, compared with just 14% of those polled on the phone.

There is a large body of research on this topic, and it shows that mode effects are most likely to occur under a few scenarios. If the question asks about a sensitive or potentially embarrassing topic, self-administered polls done online tend to yield data less skewed toward the answer respondents see as socially desirable than do interviewer-administered polls. If the question features a ratings scale, telephone poll respondents are more likely than online survey respondents to select extremely positive answers but are not more likely to give extremely negative responses.

Online polls, relative to interviewer-administered polls, also tend to have lower levels of item nonresponse (e.g., fewer “don’t know” responses) when an explicit “don’t know” or “no opinion” option is not offered. Most Pew Research Center surveys do not offer explicit “don’t know” options. Respondents to phone surveys are more likely to offer the equivalent (by telling their interviewer that they don’t know the answer or can’t answer the question) than are respondents to online surveys (by skipping the question).

How is Pew Research Center addressing this mode difference when reporting on trends?

The Center’s approach reflects the fact that some questions are at high risk of mode effects (e.g., “How would you rate your own personal financial situation?”) while others are not (e.g., “Do you approve or disapprove of the health care law passed by Barack Obama and Congress in 2010?”). Our policy is not one-size-fits all. Instead, it uses available information to try to determine which of the following three broad treatments is most appropriate:

Break the trend.

In some cases, there is compelling evidence that the online poll measured the attitude with less error (e.g., less social desirability bias) than the phone poll. When that happens, re-presenting the historic trend numbers would arguably do more harm than good, leading to confusion or erroneous reporting. “Breaking the trend” may break a researcher’s heart, but in these cases the Center will drop the prior years’ data and present only the new online estimates.

Compelling evidence that a trend has been broken comes in the form of experimental data, such as the Center’s 2014 and 2017 randomized mode experiments, or recognition that a trend question has characteristics shown in the research literature to increase the likelihood of a mode effect.

Report the new online estimate as part of a pre-existing phone trend, but draw readers’ attention to the change in mode.

In other cases, the available information suggests that the trend line is still valid and informative in the context of the new estimate. Still, the reader should be alerted that the survey moved from a phone poll to an online poll.

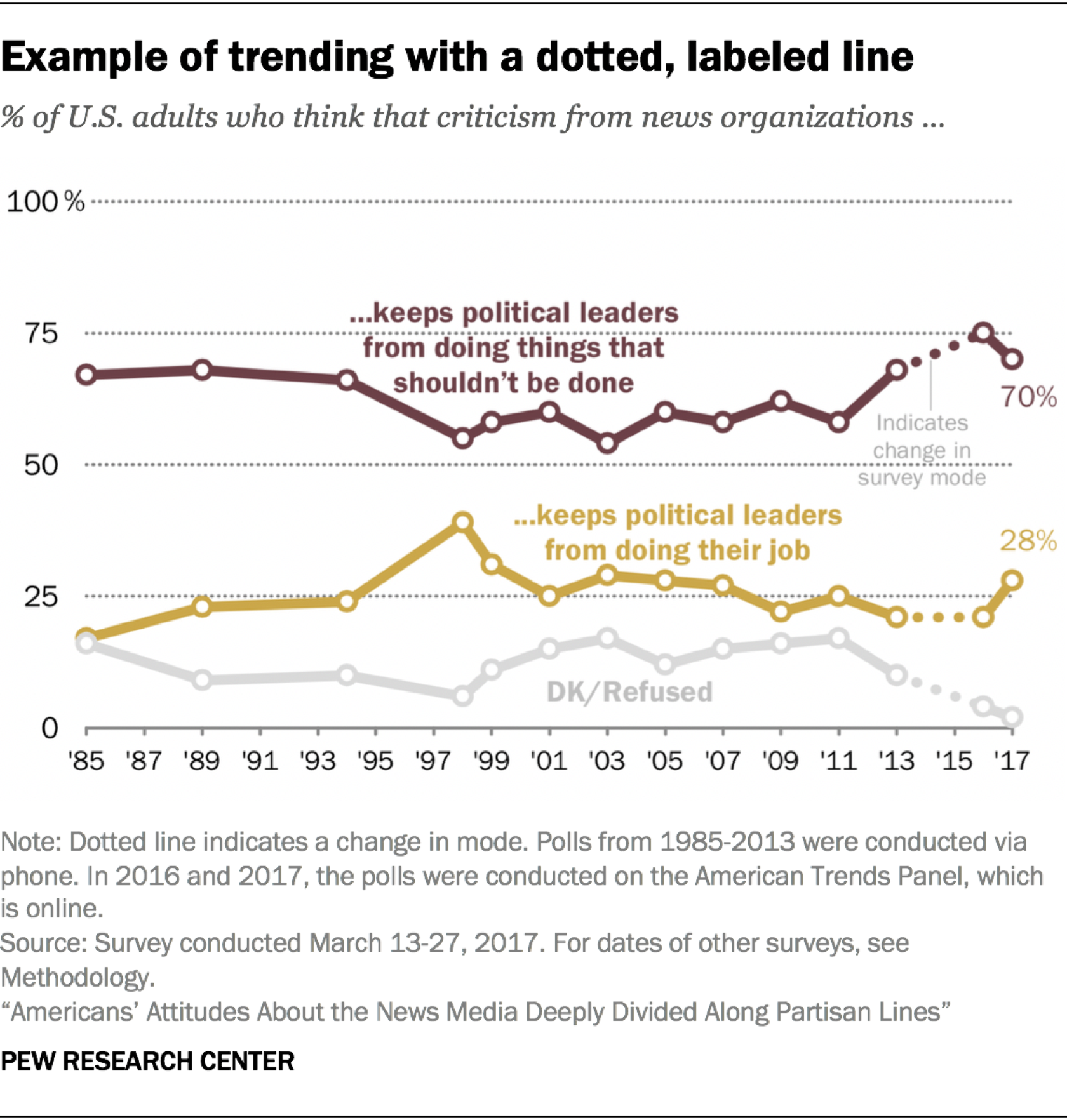

An example of this can be found in a 2017 Center report on attitudes toward the news media. Researchers updated a nearly 30-year telephone trend with new estimates from an online survey. In the graphic, they used a dotted and labeled line, as well as a footnote, to signal the mode change. In addition, language in the body of the report alerted the reader to the change: “It should be noted that prior to 2016, the question was asked by telephone rather than the web, which can elicit slightly different response patterns.” This approach, which emphasizes clear signaling of a mode change, is perhaps most appropriate in the several years immediately following a mode change, when the pattern of online estimates is still coming into view. For the next several years, the Center will continue to confront these trend issues, and during that time this middle approach of clearly calling out a mode change will be the default reporting style.

An example of this can be found in a 2017 Center report on attitudes toward the news media. Researchers updated a nearly 30-year telephone trend with new estimates from an online survey. In the graphic, they used a dotted and labeled line, as well as a footnote, to signal the mode change. In addition, language in the body of the report alerted the reader to the change: “It should be noted that prior to 2016, the question was asked by telephone rather than the web, which can elicit slightly different response patterns.” This approach, which emphasizes clear signaling of a mode change, is perhaps most appropriate in the several years immediately following a mode change, when the pattern of online estimates is still coming into view. For the next several years, the Center will continue to confront these trend issues, and during that time this middle approach of clearly calling out a mode change will be the default reporting style.

Report the new online estimate as part of a pre-existing phone trend without major emphasis.

Down the road, after several years of online measurements have been established for a trend, a subtler reporting style may be appropriate. For example, if the long arc of trending on a question bears out that a mode switch had little if any effect, then it may be reasonable to move language about the mode change from the body of charts and report text to footnotes. If, however, the data suggest that mode had a meaningful effect on the estimates, then retaining the clear signaling in charts and report text would be advisable.

Is the method of interviewing the only source of differences between older phone estimates and newer online estimates?

Not necessarily. If an older phone estimate differs from a newer online estimate using the exact same question wording, at least four factors could be contributing to the difference. These are:

Real change over time

Ideally, the difference is attributable to real change in the population rather than an artifact of how the poll was conducted.

Measurement differences

As discussed above, the interviewing dynamic is different for online polling versus live telephone polling. The absence of an interviewer in online polls tends to elicit more reporting of sensitive, provocative, or extremely negative attitudes, and it tends to result in lower levels of item nonresponse unless a “don’t know” or “not sure” option is explicitly offered. Mode also affects how people cognitively process the answer choices. When taking a web survey, it is natural for people to slightly favor the first choice they read (a “primacy effect”) if they don’t have a strong opinion. On the phone, it is natural for people to slightly favor the last choice that the interviewer read to them (a “recency effect”), as that option is the easiest to remember.

Telephone and online polls also tend to differ in how often people are interviewed. Telephone polls are usually one-off surveys in which a new, fresh sample of the public is interviewed each time a poll is fielded. Online survey panels, by contrast, recruit a sample of the public to take surveys on an ongoing basis (e.g., once a month). When the same group of people are interviewed multiple times, it is possible for the repeated measurements to have an effect (e.g., by making the survey topic more salient to the panelists). While such “conditioning” of survey respondents does not appear to be a major threat in panels that ask about many different topics – like the American Trends Panel – researchers need to remain vigilant about this risk.

Weighting differences

The weighting protocol for Pew Research Center telephone and online polls is similar, but there are some differences. Both the Center’s phone and online polls use a process called raking to ensure that the weighted data is nationally representative with respect to major demographic characteristics like age, race, Hispanic background, ethnicity, region, sex and education. The Center’s polls conducted online with the American Trends Panel feature some additional adjustments, however. For example, the online polls are also raked to population targets for volunteerism and internet access to address the fact that adults who are less civically engaged or who do not use the internet tend to be underrepresented in online panels.

Sample composition differences

While Pew Research Center’s telephone and online polls are recruited offline to be nationally representative using random sampling, the profile of people interviewed under each method can differ somewhat. The Center’s telephone polls draw random samples of cellphone and landline numbers using a process called random-digit dialing. The Center’s online American Trends Panel, by contrast, is now recruited using random samples of residential postal addresses. In addition, some subgroups are more likely to participate in surveys by phone versus online. For example, telephone survey samples often skew older while online survey samples sometimes skew younger. The weighting procedures mentioned above are used to try to address such patterns, but some differences attributable to the profile of who responded to the poll can persist.

When mode difference occur, they may reflect a combination of several of these factors.

Can anyone respond to Pew Research Center polls now that they are conducted online?

No. While some online polls allow anyone to participate, the Center continues to use scientific, probability-based sampling. Controlled, scientific sampling ensures that people can’t participate unless they are invited to do so. The Center’s recruiting for its polls takes place offline (that is, not using the internet) through the mail for two main reasons. First, a sizable share of the public does not have internet access. Second, no comprehensive list of email addresses exists for all adults who do have access to the internet. This means there is currently no way to select survey samples online in a way that covers the entire population. Offline recruitment means that internet access – in the form of a tablet and data plan – can be provided to those who do not already have it, ensuring that all Americans have some chance of being interviewed in this new era of online polling.

Has the polling industry gone through a major mode change before?

Yes. In the 1970s and 1980s, many national pollsters transitioned from in-person interviewing (in which interviewers knocked on doors across the country) to live telephone interviewing. Many of the same questions and concerns that the industry faces now existed back then.

Does the Center’s transition signal that there is a problem with phone polling?

The Center’s increasing use of the online American Trends Panel and its movement away from phone polling is, in part, a reaction to the challenges associated with phone polling. That said, telephone polling can still perform well, as shown in the 2018 midterm election. Pre-election polls in 2018 – including those conducted by phone with live interviewers – were more accurate, on average, than midterm polls since 1998.

Is Pew Research Center completely finished doing phone polling in the U.S.?

No. While a majority of the Center’s domestic polling is now done online, some phone polling continues. In some cases, it is feasible to conduct a phone poll at the same time as an online poll to get some information about the size of the mode effect in a long-standing trend. Telephone also remains a good option for studies of certain special populations.

As survey research works its way through the second great mode shift of its relatively short existence, Pew Research Center is committed to experimenting with, evaluating and reporting on the performance of online surveys.

Related:

Main report: Growing and Improving Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel

Q&A: Why and how we expanded our American Trends Panel to play a bigger role in our U.S. surveys

Response rates in telephone surveys have resumed their decline