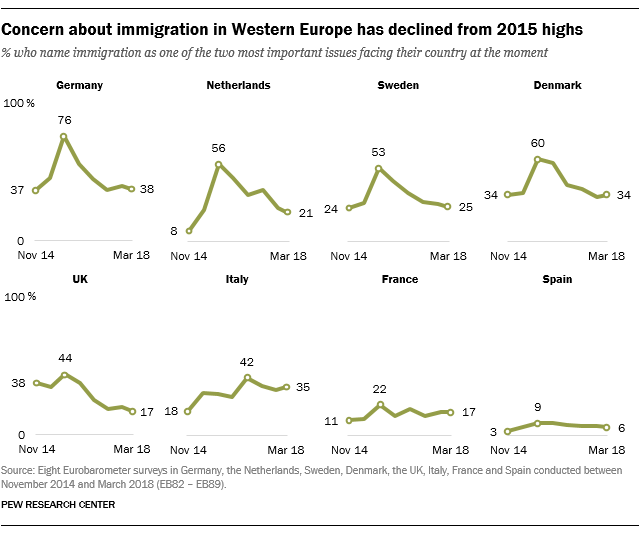

As the surge in immigration to Europe drops back to pre-2015 levels, the fever pitch of concern has also abated across eight key countries in Western Europe, according to surveys conducted by the European Union’s Eurobarometer between 2014 and 2018. Today, a median of 23% in these countries name immigration as one of the top two problems facing their country, down from a median of almost half in November 2015.

But while anxieties have decreased dramatically across the EU as immigration flows have slowed, immigration still remains a top concern for many Western Europeans. For example, in both Denmark and Germany, more people name the issue as a problem facing their country than any other (34% and 38%, respectively). And while only a minority of people are concerned in most countries, they do tend to be vocal. Immigration issues, often raised by far-right parties, have rocked coalitions in Germany, and been front and center in recent elections in Italy and Sweden.

But while anxieties have decreased dramatically across the EU as immigration flows have slowed, immigration still remains a top concern for many Western Europeans. For example, in both Denmark and Germany, more people name the issue as a problem facing their country than any other (34% and 38%, respectively). And while only a minority of people are concerned in most countries, they do tend to be vocal. Immigration issues, often raised by far-right parties, have rocked coalitions in Germany, and been front and center in recent elections in Italy and Sweden.

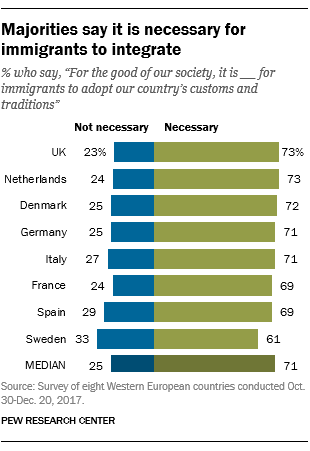

A major concern about immigration among people in the countries surveyed is whether immigrants will make the effort to integrate into their new country. In a late 2017 Pew Research Center survey, majorities in all countries agreed that, for the good of their society, immigrants should adopt the country’s customs and traditions.

A major concern about immigration among people in the countries surveyed is whether immigrants will make the effort to integrate into their new country. In a late 2017 Pew Research Center survey, majorities in all countries agreed that, for the good of their society, immigrants should adopt the country’s customs and traditions.

When it comes to which aspects of a country’s customs and traditions are most important for immigrants to adopt, past Pew Research Center surveys have found that most Western Europeans think speaking the country’s language and respecting the country’s institutions and laws are very important to truly share the national identity of a country. But sizable minorities also think it’s important to have been born in the country or to be a Christian.

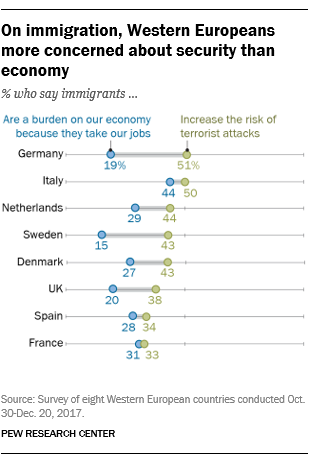

There is relatively widespread agreement about the importance of cultural integration, but Western Europeans are more divided in their views of immigration’s impact on the economy and security. For most, concerns center more on the risk of terrorism than on burdening the economy. In all countries, more people say that immigrants increase the risk of terrorism in their country than say that immigrants burden their country’s economy. For example, more than half of Germans say that immigrants increase the risk of terrorism, while only 19% see them as a drain on the economy.

There is relatively widespread agreement about the importance of cultural integration, but Western Europeans are more divided in their views of immigration’s impact on the economy and security. For most, concerns center more on the risk of terrorism than on burdening the economy. In all countries, more people say that immigrants increase the risk of terrorism in their country than say that immigrants burden their country’s economy. For example, more than half of Germans say that immigrants increase the risk of terrorism, while only 19% see them as a drain on the economy.

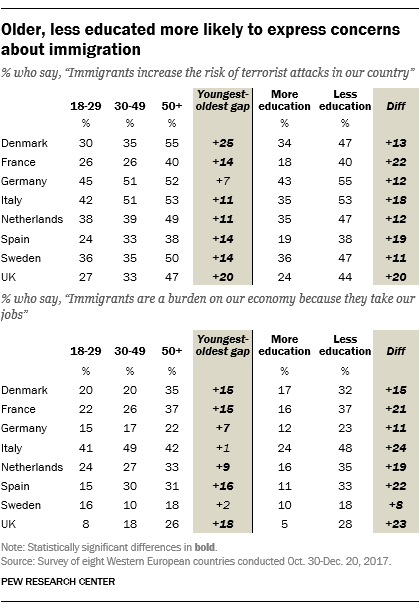

Ideology plays a large role in determining many of these attitudes. People on the ideological right are more likely than those on the left to say immigrants need to integrate into a country’s society, that they increase the risk of terrorism, and that they are an economic burden. Beyond ideology, education level also affects attitudes. People with lower levels of education are significantly more likely to see the negative sides of immigration. In Italy, for example, around half of those with a secondary degree or less (48%) say immigrants are a burden on the economy, compared with 24% of those with more than a secondary degree.

Age is also a key factor, with older people much more likely to see immigrants in a negative light. For example, in the United Kingdom, around half of those ages 50 and older say immigrants increase the risk of terrorism, compared with only around a quarter of those under 30.

Age is also a key factor, with older people much more likely to see immigrants in a negative light. For example, in the United Kingdom, around half of those ages 50 and older say immigrants increase the risk of terrorism, compared with only around a quarter of those under 30.

Concerns about the economic effects of immigration are somewhat related to people’s financial circumstances. In most countries surveyed, those with lower incomes are more likely than those with higher incomes to feel that immigrants burden their economies. But, in most countries, even those with lower incomes feel that immigrants strengthen the economy more than they burden it.

Similarly, there are few differences between men and women when it comes to the importance of cultural integration. But, in five countries — the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Sweden and the UK — men are more likely than women to think that immigrants increase the risk of terrorist attacks.