California Gov. Gavin Newsom this week announced a moratorium on executions in his state, a move that will affect 737 inmates on the largest death row in the country. The decision marks a significant change in policy, but not in practice: California is one of 11 states that have capital punishment on the books but have not carried out an execution in more than a decade.

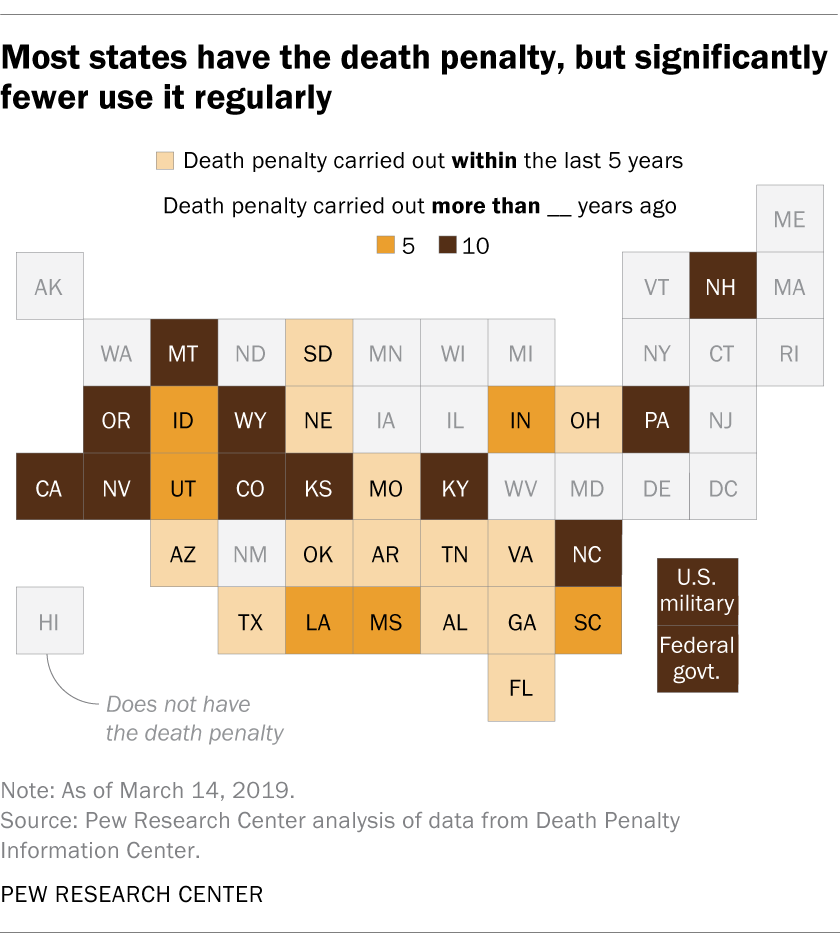

Overall, 30 states, the federal government and the U.S. military authorize the death penalty, while 20 states and the District of Columbia do not, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, an information clearinghouse that has been critical of capital punishment. But more than a third of the states that allow executions – along with the federal government and the U.S. military – haven’t carried one out in at least 10 years or, in some cases, much longer.

Overall, 30 states, the federal government and the U.S. military authorize the death penalty, while 20 states and the District of Columbia do not, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, an information clearinghouse that has been critical of capital punishment. But more than a third of the states that allow executions – along with the federal government and the U.S. military – haven’t carried one out in at least 10 years or, in some cases, much longer.

California’s last execution took place in 2006. The other states that have capital punishment but haven’t used it more than a decade are New Hampshire (last execution in 1939); Kansas (1965); Wyoming (1992); Colorado and Oregon (both 1997); Pennsylvania (1999); Montana, Nevada and North Carolina (all 2006); and Kentucky (2008).

The last federal execution happened in 2003. And while the military retains its own authority to carry out executions, it hasn’t done so since 1961.

There are wide variations in the number of people who are on death row in the 11 states and federal entities that have the death penalty but haven’t used it in at least a decade. While California has more than 700 people on death row, New Hampshire has only one. (New Hampshire’s state House of Representatives this month voted overwhelmingly to abolish the death penalty and replace it with life without parole, but it’s unclear if the bill will become law. Gov. Chris Sununu vetoed a similar effort last year.)

Nationally, the number of death row inmates fluctuates almost daily as new death sentences are imposed, executions are carried out and prisoners die of other causes or otherwise leave death row, including through exoneration.

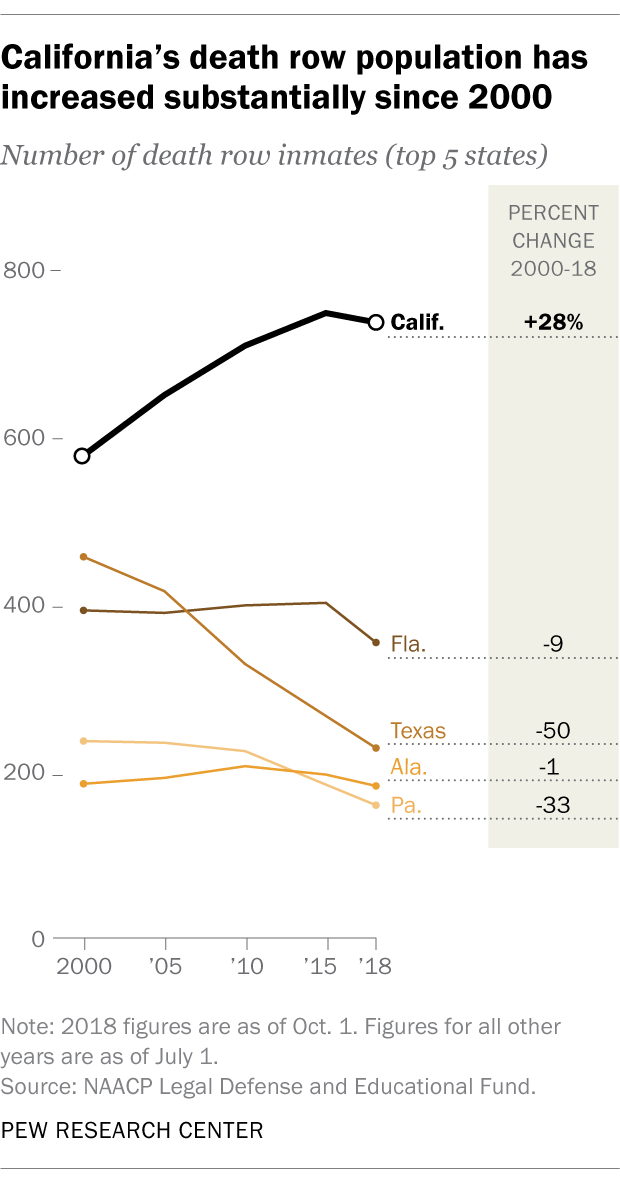

California’s death row has grown by nearly 100 inmates, or 14%, since January 2006, when it carried out its last execution, and by 28% since 2000, according to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which tracks death row populations in all states. (The most recent available data for all states are as of October 2018.) The increase reflects the fact that California juries have continued to sentence convicted defendants to death, even as executions themselves have been on hold in recent years amid legal and political disputes that predated Newsom’s formal moratorium.

California’s death row has grown by nearly 100 inmates, or 14%, since January 2006, when it carried out its last execution, and by 28% since 2000, according to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which tracks death row populations in all states. (The most recent available data for all states are as of October 2018.) The increase reflects the fact that California juries have continued to sentence convicted defendants to death, even as executions themselves have been on hold in recent years amid legal and political disputes that predated Newsom’s formal moratorium.

One stark reflection of the longtime suspension of capital punishment in California is that executions are the third most common cause of death for those on death row, following natural causes and suicide, according to data from the state’s corrections department. Just 15 of the 135 California death row inmates who have died since 1978 were executed.

The federal government’s death row has also grown substantially since the last federal execution. There are currently 62 federal inmates sentenced to death, up from 26 in January 2003 (just before the federal government’s most recent execution).

The increases in the number of people on death row in California and at the federal level run counter to the national trend. Nationwide, the number of inmates on death row fell 26% between 2000 and 2018, from 3,682 to 2,721, according to the NAACP’s figures.

A variety of factors explain this decrease. For one thing, 892 executions were carried out between 2000 and 2018, including 359 in Texas alone, according to a database compiled by the Death Penalty Information Center. Many other death row prisoners have died of other causes. Another 81 were removed from death row between 2000 and 2018 because they were exonerated, whether by acquittal, dropped charges or pardons. And the number of new defendants sentenced to death has declined sharply, from 223 in 2000 to just 42 last year.

Legal and political factors have played a prominent role in several of the states that have the death penalty but have not carried out an execution for 10 years or more. In California, courts struck down the state’s lethal injection protocol in 2006, and the state did not propose a replacement method until years later. In 2016, California voters approved a ballot initiative intended to speed up the death penalty process, but Newsom said this week that no executions will occur in the state while he remains governor.

California is not the only state whose governor has declared a moratorium on executions even as capital punishment remains on the books. The governors of Oregon and Pennsylvania, for example, have also suspended executions in their states.

Nationwide support for the death penalty ticked up in 2018, according to a Pew Research Center survey. A narrow majority of U.S. adults (54%) said they support the death penalty for those convicted of murder, compared with 39% who opposed it. But support for capital punishment remains much lower than in the 1990s or throughout much of the 2000s.

Note: This is an update to a post originally published Aug. 10, 2018.