Earlier this year, Democrats had hopes that a spate of special elections to the U.S. House of Representatives would flip at least a couple of Republican-held seats their way. But the GOP held onto all four of the seats that opened up when their former occupants took jobs in the Trump administration. The only Democratic special election win came in a California district the party already held, meaning there was no net change in the House’s partisan balance, which favors Republicans by 240 to 194. (A vacant Utah seat, represented until last month by Republican Jason Chaffetz, will be filled in yet another special election this fall.)

That lack of dramatic change is very much in line with recent history, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of special election data. Of the 130 House special elections since 1987, only 21 (16%) resulted in a seat changing from Republican to Democratic or vice versa – the last one nearly five years ago.

That lack of dramatic change is very much in line with recent history, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of special election data. Of the 130 House special elections since 1987, only 21 (16%) resulted in a seat changing from Republican to Democratic or vice versa – the last one nearly five years ago.

(In general, House seats rarely flip from one party to the other: Last year, for instance, only 10 House seats flipped parties. Along with Democratic wins in two of three newly redrawn districts, the party had a net gain of six seats.)

When House seats do flip in a special election, there’s often some unusual factor at play, such as a scandal or a split in the dominant party. That was emphatically the case in 2012 in Michigan’s 11th District, when incumbent Republican Rep. Thad McCotter was denied a spot on the primary ballot because nearly all the signatures on his nominating petitions were fake. McCotter resigned in the ensuing scandal, and there were two elections that November: a regular one for the incoming 113th Congress, and a special election for what was left of McCotter’s term in the 112th Congress. A Democrat won the special election, but a different Democrat lost the general, meaning the seat flipped from Republican to Democratic and back again in the space of two months.

Before the turmoil in Michigan’s 11th, the three previous special election flips also came after scandal-fueled resignations – all, as it happens, in New York state. Republican Tom Reed won Democrat Eric Massa’s seat in 2010 after Massa stepped down amid sexual-misconduct allegations; Democrat Kathy Hochul won Republican Chris Lee’s seat in May 2011 after the married congressman admitted soliciting a woman online; and Republican Bob Turner was elected four months later to replace Democrat Anthony Weiner after Weiner’s sexting scandal.

It’s not uncommon for special elections to draw crowded fields of candidates, especially in states with all-party primaries and no runoffs. In eight of the 21 special-election flips we counted since 1987, the winner received less than 50% of the vote. For instance, the ballot for the May 2010 special election in Hawaii’s 1st District listed no fewer than 14 candidates – five Republicans, five Democrats and four independents. GOP candidate Charles Djou won the formerly Democratic seat with just 39.4% of the vote. But that November, against just one opponent (a Democrat), Djou lost.

By and large, House special elections are low-turnout events. Excluding the 20 special elections held concurrently with regular elections, turnout in the House special elections we examined was, on average, about half that of the previous general election in the same district. The most extreme case occurred in November 2008, when a special election was held to fill the remaining weeks in Democratic Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones’ term representing Ohio’s 11th District. Democrat Marcia Fudge had already won the regular election for the incoming Congress two weeks earlier, when nearly 250,000 voters cast ballots; Fudge was unopposed in the separate special election, and just 8,844 people voted (8,597 of them for Fudge).

By and large, House special elections are low-turnout events. Excluding the 20 special elections held concurrently with regular elections, turnout in the House special elections we examined was, on average, about half that of the previous general election in the same district. The most extreme case occurred in November 2008, when a special election was held to fill the remaining weeks in Democratic Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones’ term representing Ohio’s 11th District. Democrat Marcia Fudge had already won the regular election for the incoming Congress two weeks earlier, when nearly 250,000 voters cast ballots; Fudge was unopposed in the separate special election, and just 8,844 people voted (8,597 of them for Fudge).

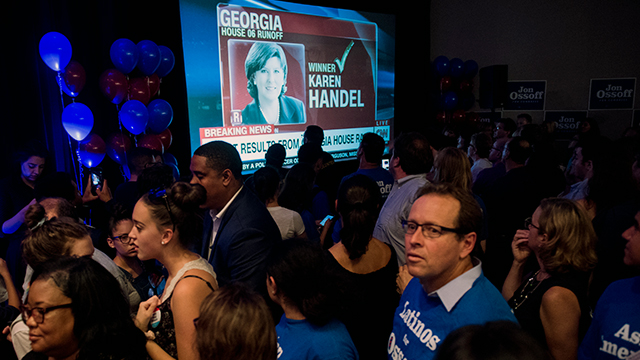

Last month’s special runoff in Georgia’s 6th District, which ended up being the most expensive House race of any kind in U.S. history, also drew the highest relative turnout of any of this year’s special elections. More than 260,000 people (80% of the total votes in the November 2016 general election) cast ballots in the runoff between Republican Karen Handel and Democrat Jon Ossoff, the top two finishers in the 18-candidate first round. Handel edged out Ossoff by 3.6 percentage points, retaining the seat for the GOP.

States sometimes will schedule a special election for the same day as the regular election, partly to save on the expense of holding a separate election and partly to give the winner a bit of a seniority boost (because they can take their seats immediately, rather than waiting till January for the new Congress to convene). In such cases special election turnout is much higher, relatively speaking: In the 20 cases of concurrent special and general elections that we analyzed, turnout in the special elections averaged just 4.2% below the concurrent general elections. In three instances, in fact, more people voted in the special election than in the concurrent general. (In only five of the non-concurrent special elections did turnout exceed the previous general election, which in each case featured a longtime incumbent who seldom if ever faced serious opposition).

Special elections haven’t attracted a great deal of scholarly attention, but what research there is generally finds them to be driven more by local than national political forces. The authors of a 1999 study of special elections, for instance, concluded that by and large, “special elections are as vulnerable to the constituency characteristics and candidate-specific attributes that structure other open-seat outcomes.” Even special elections that result in House seats flipping parties, they wrote, “can be viewed as the product of normal electoral circumstances and not referenda on the [presidential] administration.”