Prior to the Civil War, higher education opportunities were virtually nonexistent for nearly all black Americans. In the years following the war, more colleges sprang up to meet the educational needs of the newly freed black population. Congress defines a historically black college or university (HBCU) as a school “established prior to 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans.”

One of these institutions – Howard University – will celebrate its 150th anniversary on March 2. Founded in 1867, the Washington, D.C., university is not the oldest institution dedicated to educating black Americans, but it has become one of the largest historically black colleges in the nation.

One of these institutions – Howard University – will celebrate its 150th anniversary on March 2. Founded in 1867, the Washington, D.C., university is not the oldest institution dedicated to educating black Americans, but it has become one of the largest historically black colleges in the nation.

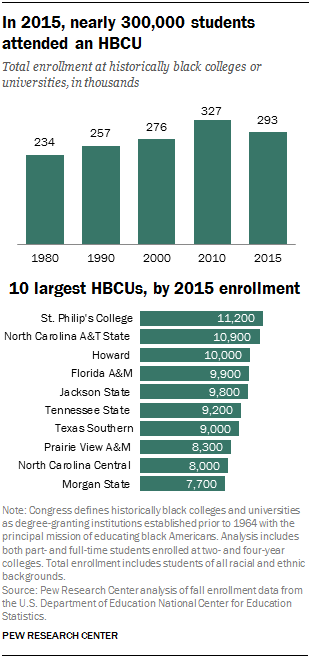

Today, there are 101 HBCUs across the United States and the U.S. Virgin Islands – roughly the same as in 1980, but down since the 1930s when there were 121 of these institutions, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Overall enrollment at these schools, including non-black students, has risen over the past several decades, albeit at a much slower rate than at universities overall. NCES figures show that in fall 2015, the combined total enrollment of all HBCUs was 293,000, compared with 234,000 in 1980. By comparison, enrollment at all universities and colleges nearly doubled during this time.

Howard had the third-largest enrollment of any HBCU in 2015, behind St. Philip’s College in San Antonio, Texas, and North Carolina A&T State University. In contrast to other higher-learning institutions, HBCUs tend to be relatively small, with more than half of these schools serving 2,500 or fewer students.

Some HBCUs have been in the headlines recently, with stories ranging from budgetary and school cost issues to low graduation rates. HBCU leaders are scheduled to meet with GOP lawmakers today to discuss the “challenges and importance of these institutions,” and President Donald Trump is expected to issue an executive order dealing in some way with issues facing HBCUs.

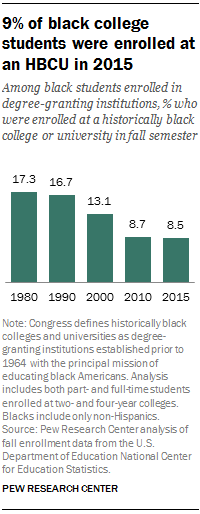

As desegregation, rising incomes and increased access to financial aid resulted in more college options for blacks, the share of blacks attending HBCUs began to shrink. By fall 1980, 17% of black students enrolled in degree-granting institutions were enrolled at an HBCU. By 2000, that share had declined to 13%, and it stood at 9% in 2015.

As desegregation, rising incomes and increased access to financial aid resulted in more college options for blacks, the share of blacks attending HBCUs began to shrink. By fall 1980, 17% of black students enrolled in degree-granting institutions were enrolled at an HBCU. By 2000, that share had declined to 13%, and it stood at 9% in 2015.

It’s difficult to determine the exact share of black students who attended historically black colleges versus predominately white institutions prior to 1968 because the government did not systematically collect racial and ethnic statistics for all higher education institutions before then, according to an NCES report. But a majority of black students were still enrolled at traditionally black colleges up until the early 1970s, according to statistics cited by the NCES.

Despite lower shares of blacks attending these institutions, HBCUs still account for a fair number of college degrees earned by black students: Around 27,000 bachelor’s degrees were awarded to black HBCU students in 2015, making up 15% of all bachelor’s degrees earned by blacks in that year. HBCUs awarded around a third of bachelor’s degrees earned by blacks in 1980.

Although these schools were established to serve black students, HBCUs have long enrolled students of all races and ethnicities – a trend that has become more prevalent over the years. The percentage of HBCU students who were either white, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, or Native American was 17% in 2015, up from 13% in 1980. Hispanic students, in particular, have seen their overall shares grow on HBCU campuses, increasing from 1.6% in 1980 to 4.6% in 2015.