The ongoing surge of refugees into Europe from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and other war-ravaged countries presents a striking demographic contrast: hundreds of thousands of predominantly young people trying to get into a region where the population is older than in almost any other place on earth.

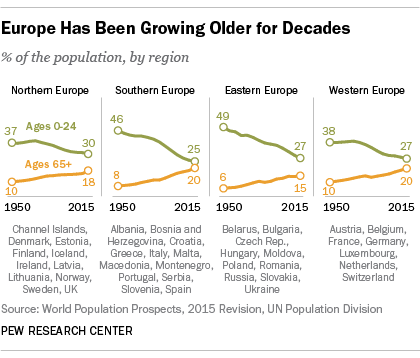

Europe has been graying for decades, primarily because of longer life expectancies and low birthrates (and, in some countries, high levels of emigration by young people of child-bearing age). In 1950, according to our analysis of data from the U.N.’s Population Division, 8% of the continent’s population was 65 or older; by 1990 that share had risen to 12.7%, and this year it’s estimated to be 17.6%.

Europe has been graying for decades, primarily because of longer life expectancies and low birthrates (and, in some countries, high levels of emigration by young people of child-bearing age). In 1950, according to our analysis of data from the U.N.’s Population Division, 8% of the continent’s population was 65 or older; by 1990 that share had risen to 12.7%, and this year it’s estimated to be 17.6%.

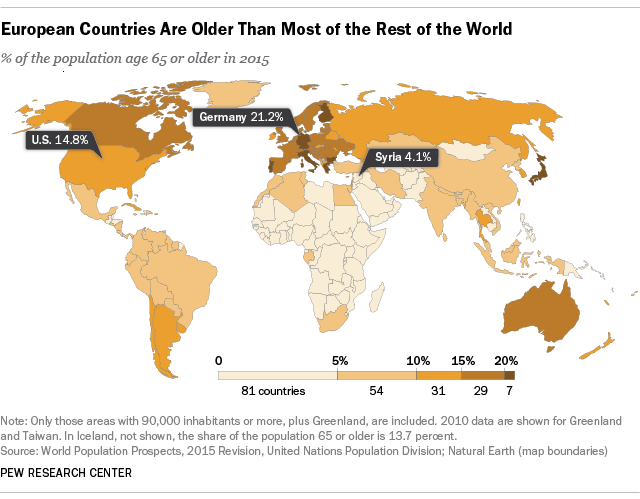

In fact, 27 of the 30 countries and territories globally with the largest 65-and-older shares are in Europe. That includes six European countries – Italy, Greece, Germany, Portugal, Finland and Bulgaria – where a fifth of the population or more is age 65 or older. (The only country with a higher 65-and-older percentage is Japan, where 26.3% of the population is at least 65.)

Coping with rising numbers of older people, and concomitant declines in working-age people, already is posing considerable social, economic and political challenges in countries such as Germany and Italy, and likely will do so in other societies as they age (including the U.S., where 14.8% of the population now is 65 or older).

Previous waves of non-European migration have already altered the culture and demographics of several European countries – think Turks in Germany, North Africans in France, or West Indians and Pakistanis in the United Kingdom. But the current wave of migration into Europe, unprecedented in its sheer scale since the end of World War II, could change the continent’s underlying dynamics.

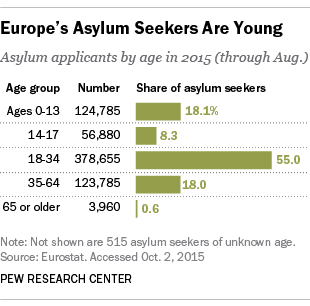

According to data compiled by Eurostat, the European Union’s statistical agency, 81% of the 689,000 people who had formally applied for asylum in EU countries this year (through August) were younger than 35; more than half (55%) were ages 18 to 34. Hundreds of thousands more refugees are expected to arrive before year’s end; one news report states that German authorities expect as many as 1.5 million asylum-seekers in that country this year.

According to data compiled by Eurostat, the European Union’s statistical agency, 81% of the 689,000 people who had formally applied for asylum in EU countries this year (through August) were younger than 35; more than half (55%) were ages 18 to 34. Hundreds of thousands more refugees are expected to arrive before year’s end; one news report states that German authorities expect as many as 1.5 million asylum-seekers in that country this year.

Some analysts argue the refugee influx could be a long-term benefit to an aging Europe, renewing the supply of younger workers on whom the continent’s retirees depend. Christian Bodewig, the World Bank’s human development sector leader for central Europe and the Baltics, wrote recently: “The real policy question for the countries of Central Europe and the Baltics today is therefore not whether to accept migrants or not but, rather, how to turn the challenge of today’s refugee crisis into an opportunity. … [Many migrants] have the potential to not just alleviate declining numbers of workers but also to boost innovation through bringing fresh ideas and perspectives.”

But others are skeptical that migration, even on the scale being seen this year, can do much more than dent the long-term aging trend. A 2001 report from the U.N.’s Population Division, for instance, estimated that Germany would need a net total of 17.8 million migrants between 1995 and 2050 (an average of 324,000 per year) to keep its overall population from shrinking; even then, the ratio of working-age people to elderly would still fall.

In addition, the near-term costs of managing the flow of refugees, providing them with housing, health care, education and other social assistance, and ultimately resettling and integrating them into new societies are daunting. Germany, by far the preferred destination for the migrants, expects to spend $6.6 billion this year alone. Turkey, which is not in the EU but houses more refugees than any other country (many of whom are making their way into EU countries) says it has spent $7.6 billion so far this year. (Turkey may get some help from the EU, which has pledged to spend at least $1.1 billion to aid nations bordering Syria that are housing millions of refugees from that country’s civil war.)

Aside from the cost, some countries have objected to taking refugees on religious, cultural or nationalistic grounds. Last month, for instance, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban stated bluntly that “We do not want a large number of Muslims in our country.” Slovakia has said it will take Syrian refugees only if they’re Christian; an Interior Ministry spokesman told the BBC, “We could take 800 Muslims but we don’t have any mosques in Slovakia so how can Muslims be integrated if they are not going to like it here?”