Hillary Clinton’s long-awaited announcement that she is indeed running for president represents more than just the possibility that she could become the first woman president, or even the first former first lady to move back into the White House by general election. Should Clinton win the Democratic nomination next year, she’d be the first former Cabinet secretary in 88 years to become a major party’s official choice for president.

In 1928, Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover won the Republican nomination and swept to victory over New York Gov. Al Smith. But things didn’t go too well for Hoover once in office (that whole Great Depression thing, you know), and since then, neither major party has nominated a current or former cabinet member. While a few former Cabinet secretaries have mounted campaigns (such as former Treasury Secretary John Connally in 1980, former Secretary of State Alexander Haig in 1988 and former Energy Secretary Bill Richardson in 2008), they’ve not gotten very far.

That’s quite a difference from the early decades of the republic, when the State Department was practically a presidential prep school (five of the first eight presidents had served previously as secretary of state), and other current or former Cabinet members frequently were nominated. But the last former secretary of state to be elected president was James Buchanan in 1856, and after the Civil War, the Cabinet began drying up as a pool of potential presidents: Only three sitting or former Cabinet members were nominated over the next six decades, and only two (William Howard Taft in 1908 and Hoover two decades later) actually won.

So what sort of experience do presidential nominees have, and how does that square with what Americans say they want in their candidates?

We researched the backgrounds of all major-party nominees and significant third-party candidates – 129 nominees in all – in each election from 1796 (the first contested presidential election) to 2012. (On several occasions, splits led to several “major-party” nominees.) Since most nominees held multiple offices prior to their presidential runs, we categorized them by the highest office they had ever held at the time they were nominated (in rank order: incumbent president, former president, vice president, Cabinet member, ambassador or equivalent, Supreme Court justice, U.S. senator, governor, U.S. representative, Army general, state-level office, no public office).

Of course, the most likely launchpad for being nominated for president is to already be president: In 31 instances, nominees either were running for re-election or were former vice presidents who’d succeeded to the presidency. Aside from that, by far the most common highest prior offices of nominees were governor (22 cases) and senator (19 cases). In 14 cases, a nominee’s highest prior office had been in the Cabinet; 11 nominees were sitting or former vice presidents (including Nixon twice, in 1960 and 1968).

Other previous highest positions were House representative (10 cases), general (6), and ambassador or equivalent (6). In four cases, ex-presidents were nominated for their old jobs (though only one, Grover Cleveland, won). Two judges have been nominated, though neither won. And in four cases, nominees had no political or governmental experience at all (such as Ross Perot in 1992 and 1996). None of them won either.

When it comes to the sort of background Americans say they want to see in presidential candidates, governing at the state level is seen more positively than extensive Washington experience. In a 2014 Pew Research Center survey, 30% said they’d be less likely to support a candidate with “many years” of experience as an elected official in Washington, while 19% would be more likely to support such a candidate. The same survey found that 33% would be more likely to support a candidate who had served as a governor, versus just 5% who said they’d be less likely. (We didn’t ask about Cabinet members.)

When it comes to the sort of background Americans say they want to see in presidential candidates, governing at the state level is seen more positively than extensive Washington experience. In a 2014 Pew Research Center survey, 30% said they’d be less likely to support a candidate with “many years” of experience as an elected official in Washington, while 19% would be more likely to support such a candidate. The same survey found that 33% would be more likely to support a candidate who had served as a governor, versus just 5% who said they’d be less likely. (We didn’t ask about Cabinet members.)

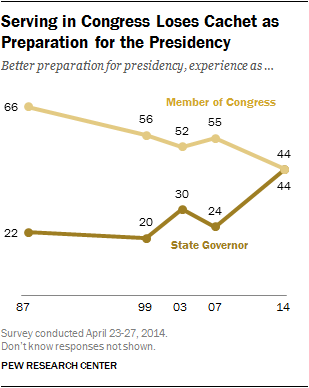

A separate measure found that congressional service has lost ground to gubernatorial experience in terms of which is perceived as better preparation for the presidency. As recently as 2007, more than twice as many people said serving in Congress was better preparation than being a state’s governor; last year, both options were tied.