The U.S. Supreme Court last week revived a previously dismissed case that looks at whether, and under what circumstances, employers should provide accommodations to pregnant employees who are “similar in their ability or inability to work” to other employees with other medical conditions.

The case involves Peggy Young, who filed a discrimination lawsuit against UPS, her former employer. Young, who at the time worked as a part-time driver, was told to avoid heavy lifting while pregnant. UPS refused to give her lighter duties and placed her on unpaid leave. In 2008, she sued, citing the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978.

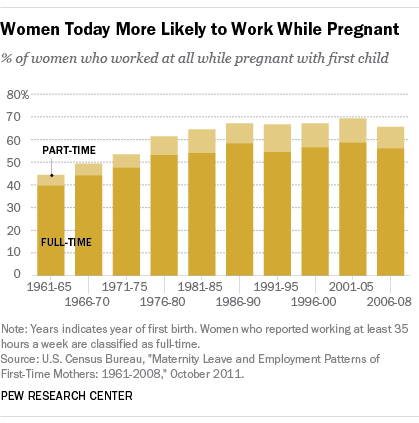

Young’s situation of working while pregnant is much more common today than it was before the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. Among women who had their first child in the early 1960s, just 44% worked at all during pregnancy. The likelihood that an American woman would work while pregnant increased dramatically through the 1960s and 1970s, and by the late 1980s, 67% of women pregnant with their first child remained on the job. Those rates have leveled off since then, and the latest figures show that 66% of mothers who gave birth to their first child between 2006 and 2008 worked during their pregnancy, according to Census Bureau data.

Young’s situation of working while pregnant is much more common today than it was before the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. Among women who had their first child in the early 1960s, just 44% worked at all during pregnancy. The likelihood that an American woman would work while pregnant increased dramatically through the 1960s and 1970s, and by the late 1980s, 67% of women pregnant with their first child remained on the job. Those rates have leveled off since then, and the latest figures show that 66% of mothers who gave birth to their first child between 2006 and 2008 worked during their pregnancy, according to Census Bureau data.

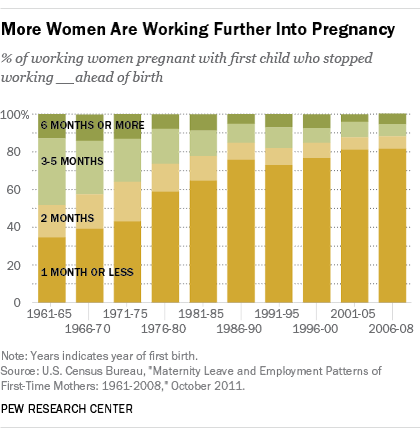

The data suggest that not only are a higher share of women expecting their first child continuing to work, but they are working longer into their pregnancy. In the early 1960s, most working women pregnant with their first child (65%) stopped working more than a month before the birth, while just about a third (35%) continued working into their final month. By the late 2000s, that trend had reversed. About eight-in-ten pregnant workers (82%) continued in the workplace until within one month of their first birth, compared with just 18% who stopped working before then.

The data suggest that not only are a higher share of women expecting their first child continuing to work, but they are working longer into their pregnancy. In the early 1960s, most working women pregnant with their first child (65%) stopped working more than a month before the birth, while just about a third (35%) continued working into their final month. By the late 2000s, that trend had reversed. About eight-in-ten pregnant workers (82%) continued in the workplace until within one month of their first birth, compared with just 18% who stopped working before then.

Women are also returning to work much sooner after their first birth than in previous decades. Among women who worked during their pregnancy and had their first child in the early 1960s, just 21% had returned to work six months after their child’s birth. Among those who had their first birth between 2005 and 2007, 73% had done so.

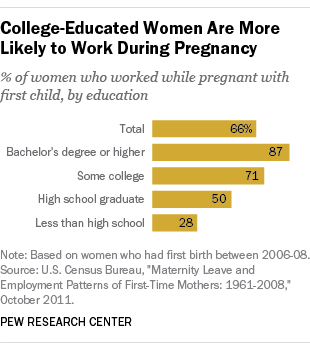

Highly educated women are more likely to work during the pregnancy preceding their first birth than less educated women. The latest data indicate that 87% of women with a bachelor’s degree or higher worked while pregnant with their first child. By contrast, just 28% of women without a high school diploma worked while pregnant with their first child, a disparity that parallels full-time employment rates by educational attainment more broadly.

Highly educated women are more likely to work during the pregnancy preceding their first birth than less educated women. The latest data indicate that 87% of women with a bachelor’s degree or higher worked while pregnant with their first child. By contrast, just 28% of women without a high school diploma worked while pregnant with their first child, a disparity that parallels full-time employment rates by educational attainment more broadly.

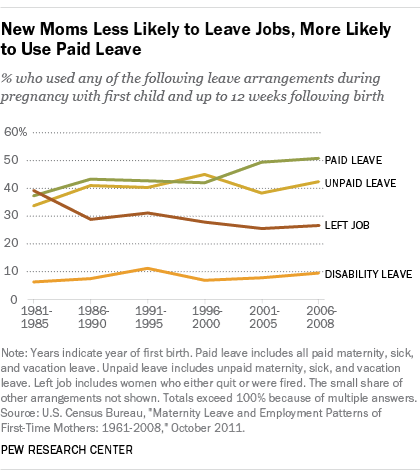

New mothers today who worked during their pregnancy are more likely than new mothers in the early 1980s to use some form of paid leave (which consists largely of maternity leave, but also includes sick and vacation leave, among other types) either while pregnant or in the 12 weeks after the birth. In the late 2000s, about half (51%) of these women used paid leave, while in the early 1980s, just 37% did.

Unlike its developed-world counterparts, the U.S. does not mandate any paid leave for new mothers under federal law, though some individual employers make that accommodation and it is mandated by a handful of individual states. By contrast, Estonia offers about two years of paid leave, and Hungary and Lithuania offer more than one year of fully paid leave, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. While U.S. law mandates no paid leave, it does require 12 weeks of protected leave to eligible employees.

Unlike its developed-world counterparts, the U.S. does not mandate any paid leave for new mothers under federal law, though some individual employers make that accommodation and it is mandated by a handful of individual states. By contrast, Estonia offers about two years of paid leave, and Hungary and Lithuania offer more than one year of fully paid leave, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. While U.S. law mandates no paid leave, it does require 12 weeks of protected leave to eligible employees.

A higher share of U.S. women who had their first child between 2006 and 2008 used unpaid leave (42%) – the kind Young received from UPS – than in the early 1980s (34%), according to census data. Conversely, the share of women who were fired from or quit their jobs declined from 39% to 27% during that same time period.

More broadly, according to a Pew Research Center survey, mothers, more than fathers, say they faced career interruptions to care for their family – either reducing work hours, taking a significant amount of time off, or quitting their jobs. These interruptions may in turn be linked to long-term earnings. In 2012, women earned 84% of what men earned on an hourly basis.