When Pew Research Center studied how Americans access and share local news in three cities, we naturally wanted to analyze the role that Facebook played as a means for people to hear about, discuss and share local news. But getting the data we needed proved challenging.

While seven-in-ten online American adults are on Facebook, most do not make the information they share fully public. Facebook allows users to adjust their privacy settings in a number of different ways, which, for researchers, means it’s harder to study the platform holistically.

We decided to focus on the information we could gather on public Facebook pages. But the question then became how to round up relevant public data from Facebook in these cities.

What we did:

Trying to contact and “friend” individual users in each city was impractical and also presented ethical challenges.

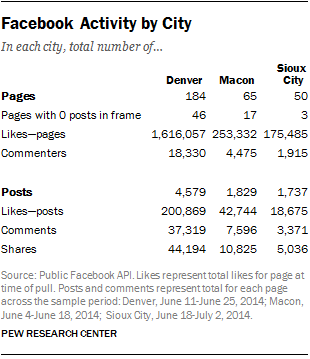

Instead, we started identifying public Facebook pages related to news providers in the three cities we selected: Denver, Macon, Ga., and Sioux City, Iowa. Generally these Facebook pages included local media organizations, local celebrities and politicians. The pages were identified as part of the “audit” of each city. Using the public Facebook Application Program Interface (API) – a way to automatically request public data from online services – we pulled all of the Facebook activity of each page during the time period studied.

This meant that the analysis ended up focusing on local news providers and the content they post, rather than what citizens shared or posted themselves – on their own, private Facebook walls – about local news. While not ideal, it seemed the most complete way to study the flow of news in each city – and to be as certain as possible that we were focusing in on that city’s news system.

The API allowed us to easily access how many Facebook posts each public page had during the 14-day time period we studied and how many “likes” and comments each one got. We also used “share” data, but with the caveat that any piece of share data available from the public API represents someone using the “Share” button on the post. It does not reflect someone sharing the post in some other way, such as copying and pasting the link in the post. Using current tools, we had no way of knowing what percentage of overall sharing on Facebook occurs using the Share button.

One way of bringing in some analysis of citizen activity was through the comments users left on public pages. The Facebook data allowed us to capture both the posted content from the managers of that page and comments made by outside users. In this case, it provided access to thousands of comments.

Analyzing comments on the public Facebook pages helped us better understand how users were interacting with these pages, but it posed an ethical question: Do regular Facebook users understand that these comments are truly public and can be accessed for this kind of research?

Since we were unable to truly answer that question, Pew Research Center chose not to publish the content of any of these comments or the names of any of the users who commented. Only the metadata was used: the time and date of the comment; whether it included a photo, video or only text; and if it included a URL. The analysis was then able to focus on the nature of the activity on these public Facebook pages.

What we learned:

In theory, Facebook opens up a space for news and information providers to experiment with new ways to get their message out, interact with the audience and enable the audience to participate.

There was some evidence of this in our analysis. For example, of the 100 most commented on posts in Denver, half included some sort of audience outreach, in which news organizations or newsmakers asked questions, made requests for photos or videos, or conducted online polls. The most commented on post in the time frame we examined, with 564 likes and 639 comments, was posted by Denver’s local CBS TV affiliate: “Would you like to see Hillary as president?”

Although the Hillary Clinton question fell into the category of national news, such instances were relatively rare among the most-commented posts we examined. In each city, at least half (58% Denver, 71% Macon, 54% Sioux City) of the most-commented posts on public Facebook pages we studied were about local news.

Our analysis found that stories that were “big” on Facebook – in other words, attracted a high number of likes and comments – were the same as those that were widely covered in the traditional local press. For example, a house explosion in Denver received the third-most attention on Facebook according to likes, comments and shares; it was also the fourth-most covered story by the mainstream press in the five days of our analysis.

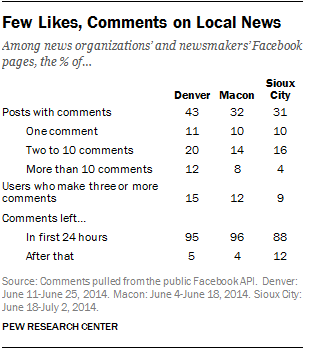

The Facebook posts that drove the most attention did so right away, but attention dropped off quickly. Almost all comments posted by users were made within the first 24 hours.

But overall, most Facebook posts we examined received few if any comments. In Macon and Sioux City, only one-in-three posts had any comments at all (43% did in Denver), and no more than one-in-ten had over 10 comments. Nor were audience members engaging in robust debate on these public pages: The vast majority of users (85% Denver, 88% Macon, 91% Sioux City) made only one or two comments on the pages of local news and information providers during the two weeks we studied.

What worked:

We know Americans increasingly use Facebook to get information and news. Our other research has found that 29% of Americans report liking or following political parties, candidates or elected officials on Facebook, while 36% say the same about news organizations, reporters or commentators and 41% follow issue-based groups.

However, the nature of Facebook as a mostly private network limits what can be learned from it. We were able to learn how news organizations and newsmakers use Facebook to get their message out and how users interacted with those messages. But this is a small sliver of the overall activity on Facebook and represents only a facet of the use of Facebook for local news. The majority of Facebook activity is still private and available only to Facebook itself. Even with just publicly available data, researchers face ethical and privacy concerns when deciding what to publish.