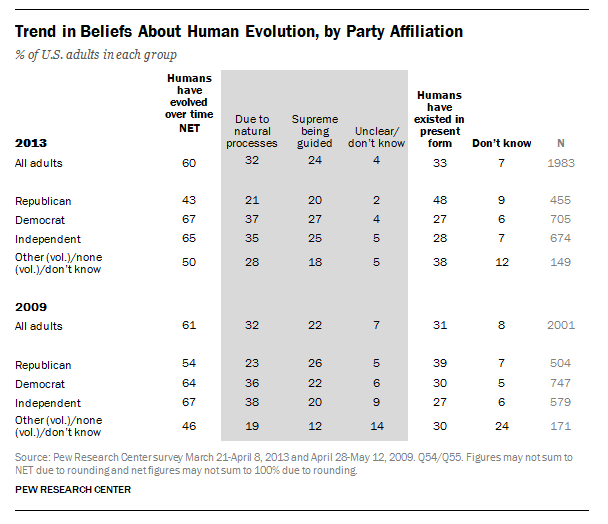

Significantly fewer Republicans believe in evolution than did so four years ago, setting them apart from Democrats and independents, according to a recent Pew Research Center study. But behind this finding is a puzzle: If the views of the overall public have remained steady, and there has been little change among people of other political affiliations, how does one account for the Republican numbers? Shouldn’t the marked drop in Republican believers cause a decline in the 60% of all adults who say humans have evolved over time?

The short answer could be that while the percentages of believers in evolution among Democrats and independents may not have changed much, the overall size of those two groups may have increased, offsetting the impact of the Republican shift.

But the findings of the survey also raise other questions: Were the people who identified as Republicans in the new survey the same as those who called themselves Republican in 2009? Are changes in beliefs occurring broadly among Republicans or are the numbers driven by a subgroup of GOP supporters (such as religious conservatives)? And, although the same questions about evolution were asked in both surveys, could the context in which they were placed have affected the outcome?

Here’s a closer look at these questions:

1How could there be so little change in overall public opinion when there’s been a substantial change in opinion among Republicans?

When overall public opinion is steady despite opinion shifts among one subgroup, logically there must be at least one other subgroup that shifts in the opposite direction and/or the size of the subgroups must be changing. When it comes to party affiliation, there are four categories of respondents that could be shifting: Republicans, Democrats, independents and those who volunteer that their party affiliation is either some other party, no party, or do not give a response.

When overall public opinion is steady despite opinion shifts among one subgroup, logically there must be at least one other subgroup that shifts in the opposite direction and/or the size of the subgroups must be changing. When it comes to party affiliation, there are four categories of respondents that could be shifting: Republicans, Democrats, independents and those who volunteer that their party affiliation is either some other party, no party, or do not give a response.

In this case, the shift among Republicans is balanced out by smaller changes in each of the other groups, resulting in stable opinion about evolution in the public overall. For example, the share of independents grew seven points from 2009 to 2013. Even though the percentage of independents saying in 2013 that humans have evolved is two points lower than in 2009, their share of the total sample grew over the four years, while that of the Republicans remained about the same. As a result the share of all adults who say humans have evolved adds to a roughly similar number (60% in 2013 and 61% in 2009).

2What would explain the change in Republicans’ views on evolution? Are they different Republicans today?

A number of astute observers of public opinion have speculated about the possible reasons behind this change. One of the most commonly talked about explanations is the idea that Republicans today must be different from Republicans in the 2009 survey when it comes to characteristics that are particularly relevant to beliefs about evolution. In other words, perhaps it isn’t that Republicans have changed their minds on this issue as much as that different people identify as Republican today than in 2009.

A number of astute observers of public opinion have speculated about the possible reasons behind this change. One of the most commonly talked about explanations is the idea that Republicans today must be different from Republicans in the 2009 survey when it comes to characteristics that are particularly relevant to beliefs about evolution. In other words, perhaps it isn’t that Republicans have changed their minds on this issue as much as that different people identify as Republican today than in 2009.

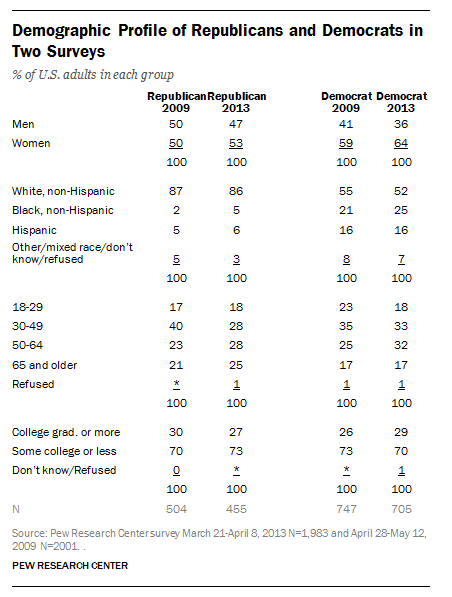

Republicans and Democrats are distinctive from each other on a number of characteristics that might be relevant to beliefs about evolution. Compared with Democrats, the Republican Party has higher numbers of men, non-Hispanic whites, and older people. But the demographic profile of Republicans is very similar in 2013 to what it was in the 2009 poll, with the exception that Republicans today are somewhat older, on average.

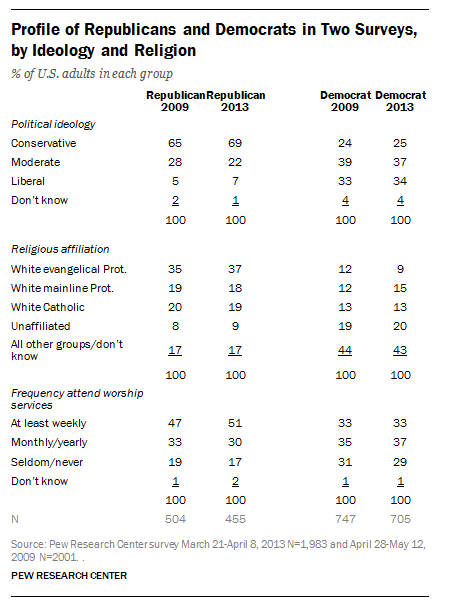

The same is true when it comes to the ideological and religious profile of Republicans and Democrats in the two surveys. Republicans in the 2013 survey are a bit more likely to identify themselves as conservative than did those in the 2009 survey (69% vs. 65% in 2009), and they are a bit more likely to say they attend worship services at least weekly (51% today, 47% in 2009), but neither difference is statistically significant.

The same is true when it comes to the ideological and religious profile of Republicans and Democrats in the two surveys. Republicans in the 2013 survey are a bit more likely to identify themselves as conservative than did those in the 2009 survey (69% vs. 65% in 2009), and they are a bit more likely to say they attend worship services at least weekly (51% today, 47% in 2009), but neither difference is statistically significant.

Nor are Republicans substantially more likely to be white evangelical Protestants today (37% compared with 35% in the 2009 poll).

Overall, while the GOP may be slightly older and more conservative today, there is no clear evidence that the composition of the party has undergone a fundamental change over this period of time.

3Are views on evolution different today among all Republicans, or only the most religious?

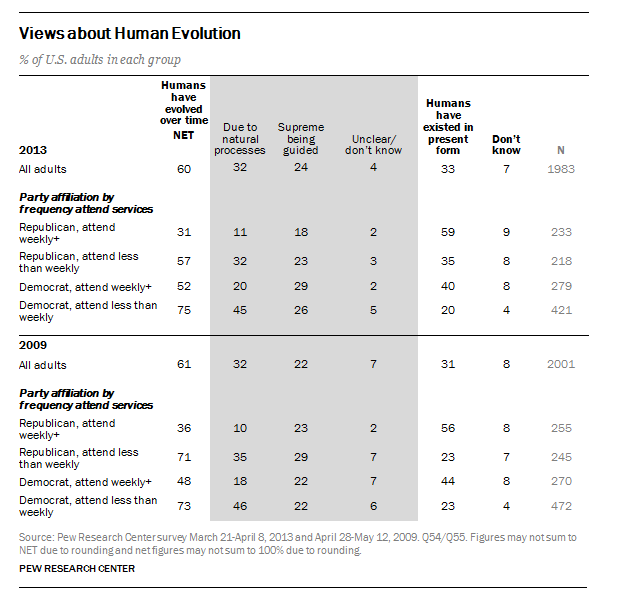

The idea of a shifting party profile also raises the question of whether the changes in beliefs are occurring among just some Republican subgroups or are broadly occurring among Republicans as a whole. Some observers have speculated that the shift might be exclusively among the most religious Republicans, reflecting a change in the overall religiosity of the party.

In fact, however, the surveys suggest that the change in views on evolution occurred especially among the less religious segments of the GOP. Among Republicans who attend worship services monthly or less often, the share who say humans have evolved over time is down 14 percentage points, from 71% in 2009 to 57% today. Among Republicans who attend services at least weekly the share who believe in evolution has gone from 36% in 2009 to 31% today, a difference that is not statistically significant.

Among Democrats, beliefs in evolution have remained about the same since 2009, irrespective of religiosity. Among Democrats who attend services at least weekly, roughly half say that humans have evolved over time (52% in 2013 vs. 48% in 2009, which is not a statistically significant change). Among Democrats who attend services less often, roughly three-quarters say humans have evolved (75% in 2013, 73% in 2009).

4Are there differences between the two surveys that could explain the increased partisan gap?

Another possibility that could explain some or all of the differences between the two surveys stems from what public opinion researchers call survey context effects. The survey conducted in 2009 focused on a range of topics, with the bulk of questions related to science or specific topics in science. The questions immediately preceding those on evolution concerned views about the effects of scientific research for society in each of four topic areas. The 2013 survey included a different set of topics with some overlapping questions on views of scientists and other occupational groups, but also including a range of other questions more closely tied to biomedical issues. The questions just prior to asking beliefs about evolution in 2013 were directly related to religion and religious beliefs.

It’s possible that the 2013 survey context “primed” a stronger underpinning of religious beliefs in how respondents thought about evolution, compared with the 2009 survey. Would that kind of context effect influence Republicans more than Democrats? If so, it could help explain the growth in the partisan gap. But we would need to conduct experimental studies to test whether this was the case with views about evolution.

5What would explain the change in Republicans’ views on evolution? Does it have to be just “one” explanation?

The data on this question do not clearly point to any single explanation for the growing partisan gap in beliefs about evolution, and it’s possible that a combination of factors underlies this pattern. For example, there could be modest changes over time in who identifies as a Republican, in addition to modest changes in the views of people who were and remain Republicans, together resulting in the rising partisan gap. The two surveys compare cross-sections of U.S. adults over time, but they do not show whether the individuals surveyed in 2009 have changed their views. Future Pew Research Center studies will study changing attitudes across a range of other topics so that we can better gauge whether the pattern we observed here is specific to evolution or perhaps related to broader sets of science topics.