The scandal that erupted in 2011 after revelations that the British tabloid News of the World had hacked the cell phones of a long list of people in the news was a major catalyst that led British lawmakers to approve guidelines for creating a new press watchdog last week.

The action came as the scandal was back in the news with the start of the trial of two former editors of Rupert Murdoch’s now-defunct newspaper—Rebekah Brooks and Andy Coulson. They are among those charged in connection with the hacking of cell phones of victims of terrorist attacks, dead soldiers, celebrities, journalists and a 13-year-old girl who was abducted and killed. Three senior journalists from the News of the World have already pleaded guilty, and in 2011, the 168-year-old tabloid was closed.

The process leading to the new press regulations began when Prime Minister David Cameron set up a series of public hearings, led by Lord Justice Leveson, in July 2011. These inquiries resulted in the November 2012 publication of a report that explored the culture, practices and ethics of the British media and provided recommendations for an independent body to replace the existing Press Complaints Commission (PCC).

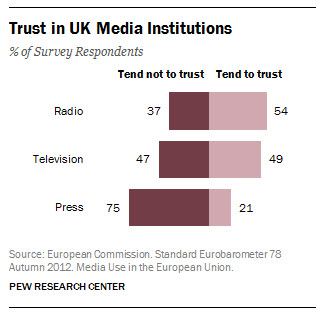

Those who pushed for the new watchdog cited the phone hacking scandal for undermining public trust in the press and reinforcing the need for more oversight. A Eurobarometer survey, sponsored late last year by the European Commission, found that only 21% of the British public trusted the print press, compared with 49% who trusted television and 54% who trusted radio. While those numbers are bleak for print outlets, they are in keeping with trust levels that have hovered between the high teens and low twenties in past Eurobarometer surveys.

Those who pushed for the new watchdog cited the phone hacking scandal for undermining public trust in the press and reinforcing the need for more oversight. A Eurobarometer survey, sponsored late last year by the European Commission, found that only 21% of the British public trusted the print press, compared with 49% who trusted television and 54% who trusted radio. While those numbers are bleak for print outlets, they are in keeping with trust levels that have hovered between the high teens and low twenties in past Eurobarometer surveys.

The government’s action (known as the Royal Charter) establishes a recognition panel that will appoint the members of the new press oversight group and ensure that it remains independent. The recognition panel is expected to be formed within six to 12 months.

When it is established, this new press watchdog will have jurisdiction in Britain, Wales and Scotland, although its authority is limited to print and online news publications. It will be empowered to establish a new code of conduct for the news industry and to initiate investigations into news outlets that may have violated the code. It can also hear complaints against news organizations brought by outside parties. In the event that it finds wrongdoing on the part of a news outlet, the body has the power to impose fines of up to 1 million pounds ($1.6 million) and to direct the news organization to publish corrections and issue apologies.

The power to impose financial sanctions, to direct corrections and apologies, and to initiate investigations on its own are tools that the previous Press Complaints Commission did not have. One limitation on the new watchdog’s authority, however, is that it will have jurisdiction only over those news outlets that agree to be governed by it.

None of this appears to be going over too well with members of the press. Earlier this year, a number of UK press associations submitted a rival proposal that was rejected by the Privy Council (the body that formally advises the Queen). After that plan was rejected, the industry, this past July, established its own watchdog group, the Independent Press Standards Organization (IPSO). But at this point, IPSO appears to have little interest in becoming the official watchdog group envisioned by the British parliamentarians.