New York City has always been a trendsetter for the rest of the country in art, fashion and cuisine. Now two researchers have documented a new demographic trend in the Big Apple that they suggest may be a glimpse of the future for other large American cities.

Researchers Ronald J.O. Flores and Arun Peter Lobo call it integration without blacks. In the past 40 years they found nearly a three-fold increase in the share of integrated New York City neighborhoods with a mix of whites, Hispanics and Asians but few, if any, blacks.

At the same time, the share of integrated neighborhoods in which blacks comprised at least 10% of the residents fell by about a third, Flores and Lobo reported in the latest Journal of Urban Affairs.

The result, they wrote, is an “emerging black/non-black color line, where Asians and Hispanics are increasingly aligned with whites while distancing themselves from blacks.”

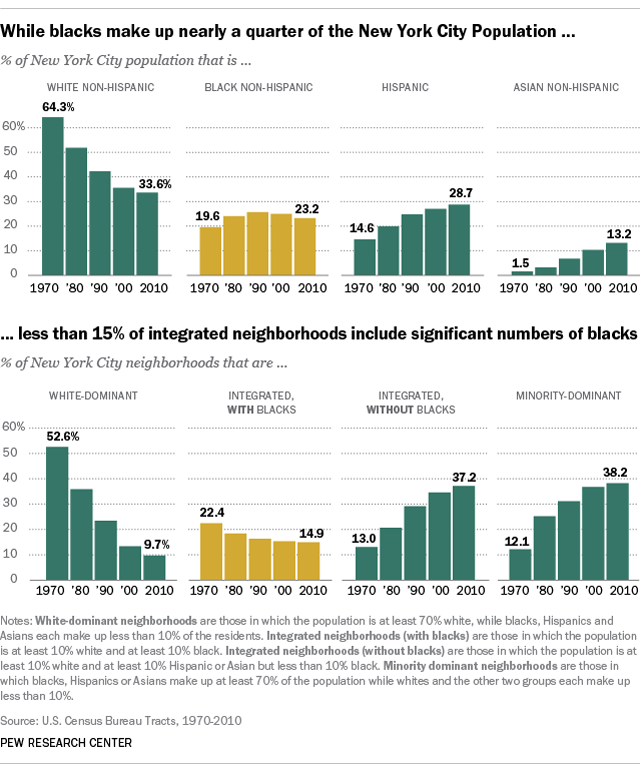

Using Census data, the researchers analyzed shifts in integration patterns in 2,111 New York City census tracts between 1970 and 2010. This period marked an explosive period of demographic change in the city: During that time the share of whites-nearly two-thirds of the population in 1970-fell by about half to roughly 33%, while the proportion of blacks remained relatively stable at about 23%. At the same time, the city’s Hispanic population doubled to 28% and the Asian share grew more than six fold to 13%.

The researchers used census tracts as proxies for neighborhoods. They defined an integrated neighborhood as one in which whites comprised more than 10% but less than 70% of all residents while some mix of blacks, Asians or Hispanics comprised the remainder.

Within these integrated neighborhoods, they identified those that were “integrated, with blacks” And those that were “integrated, without blacks.” In order to be defined as neighborhoods that were integrated with blacks, African Americans had to make up at least 10% of the residents in the census tracts. Those labeled integrated without blacks contained fewer than 10% blacks.

Since 1970, Flores and Lobo found that the proportion of “integrated, without blacks” neighborhoods nearly tripled from 13% to 37% in 2010. At the same time, the share of “integrated, with blacks” areas fell from 22.4% to 14.9%. The biggest changes were in neighborhoods where minorities made up at least 70% of the residents, which grew dramatically, and those where whites were the clear majority, which plummeted as a share of all census tracts.

For Lobo and Flores, the emerging black/non-minority color line in New York City may be a sign of things to come. It’s a claim they admit making “with caution,” given the city’s distinct history and high levels of black and white residential segregation. Still, they suggest that what “we see in New York City now may be a glimpse of what we could see in the nation’s future.”

Residential racial integration can be measured in a number of ways, and different measures can lead to different conclusions. For another perspective, see this paper that suggests the emergence of stable and flourishing “global neighborhoods” where growing numbers of whites, blacks, Asians and Hispanics call home.