As Congress debates a comprehensive immigration bill, one key element under consideration is whether to offer a pathway to citizenship for the nation’s estimated 11.1 million unauthorized immigrants. If a bill were to pass including such a provision, how many would take advantage of the opportunity?

The answer is of course speculative. The Pew Hispanic Center has conducted surveys and analyses of government data that offer some insights – but not all of them point in the same direction.

A survey we conducted in 2012 found that more than nine-in-ten (93%) Hispanic immigrants who are not citizens said they would like to become a U.S. citizen. This was true both for those who are legal permanent residents (96%) and for those who aren’t (92%). The vast majority in the latter group is in the country illegally.

Despite this near universal expression of a desire for citizenship, our analysis of government data shows that a majority of Hispanic immigrants who are eligible to seek citizenship have not yet taken the opportunity to do so. Only 46% of Hispanic immigrants eligible to naturalize (become citizens) have, compared with 71% percent of all immigrants who are not Hispanic and are eligible to naturalize. The naturalization rate is particularly low among the largest group of Hispanic immigrants – Mexicans – among whom just 36% have naturalized.

Our 2012 survey also found that the reasons most often cited for not seeking citizenship were not speaking English (as required by a citizenship test), not being able to afford it (it costs $680 to apply for citizenship), and just not yet having gotten around to trying.

There is one more indicator, albeit an indirect one, of what might happen should comprehensive immigration reform offer a pathway to legal status.

There is one more indicator, albeit an indirect one, of what might happen should comprehensive immigration reform offer a pathway to legal status.

Last year, the Obama administration created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which provides temporary relief from deportation to qualifying young adults ages 15 to 30 who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children. The program also provides a work permit to those who are awarded relief from deportation. The program does not provide a pathway to citizenship, but does offer temporary legal status – a feature likely to be a part of any comprehensive immigration bill.

This program is directed at a group of young immigrants, also known as DREAMers, who largely grew up in the U.S.

When the program was announced, we estimated that up to 950,000 young unauthorized immigrant adults were immediately eligible to apply for the new program. We also estimated that another 770,000 young unauthorized immigrants were potentially eligible in the future should their circumstances change.

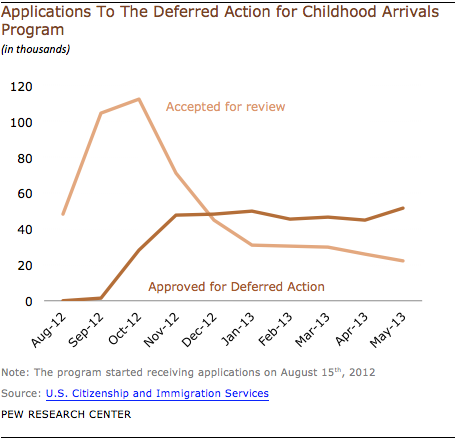

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) began to accept applications for the deferred action program beginning August 15, 2012. Since then, the latest data (through May 31, 2013) shows that 520,000 young immigrants have submitted an application —more than half (55%) of all those estimated to be potentially eligible for the program. In addition, 51% of applications submitted to date were transmitted to the USCIS in the first two and a half months of the program, reaching a peak of 113,000 applications in October, 2012. Since then, the number of submissions has decreased to just above 20,000 in the latest month available. Among those who have applied, over three-fourths (76%) are of Mexican origin.

Meanwhile, the number granted temporary relief from deportation stands at 365,000 as of May 2013, with about 45,000 granted temporary relief per month since November 2012. Overall, 70% of all applications submitted to the program have been approved for temporary relief from deportation.

It remains to be seen whether immigration reform will pass in Congress. But the data indicate varying levels of interest among immigrants—including unauthorized immigrants— in pursuing U.S. citizenship, or at least in normalizing their status.