Eurostat, the European statistical agency, today released European unemployment figures for April, and the picture is not pretty.

As the continent struggles to climb out of its double-dip recession, widespread public concern about joblessness is fueling the debate over whether it is now time to stimulate the economy to spur job creation or to continue fiscal retrenchment to cut public debt. (Earlier this week, the European Union’s executive arm gave France, Spain and five other nations more time to meet their deficit-reduction targets, but simultaneously warned EU members against taking on more debt to fund stimulus efforts.)

As the continent struggles to climb out of its double-dip recession, widespread public concern about joblessness is fueling the debate over whether it is now time to stimulate the economy to spur job creation or to continue fiscal retrenchment to cut public debt. (Earlier this week, the European Union’s executive arm gave France, Spain and five other nations more time to meet their deficit-reduction targets, but simultaneously warned EU members against taking on more debt to fund stimulus efforts.)

The economic downturn has exacted a heavy toll on employment across Europe. In the 27-member EU, 11% are jobless, unchanged from March. Unemployment was even higher among the 17 nations that use the euro: 12.2% in April, up a tenth of a percentage point from March.

The ranks of the unemployed include 26.8% of the Spanish and 17.8% of the Portuguese, but only 5.4% of the Germans. Youth unemployment—those people aged 25 and under–was even higher: 56.4% in Spain, 42.5% in Portugal and 40.5% in Italy. (Greece posted the highest jobless rates, 27% for the entire population and 62.5% among youth, but as those figures are from February they’re not directly comparable.)

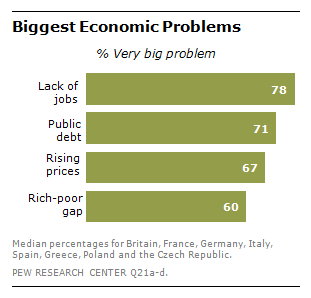

European publics are clear: They see such unemployment as their number-one economic problem. In seven of eight of the nations surveyed by the Pew Research Center in March, joblessness was seen as a country’s premier economic challenge.

Over nine-in-ten Greeks (99%), Italians (97%) and Spanish (94%) thought a lack of jobs was a very big problem in their country. Their intensity of concern was shared by eight-in-ten French. It is noteworthy, however, that in Germany, where the jobless rate was only 5.4% at the time of the survey, just 28% complained that unemployment was a very big problem.

Not surprisingly, given such sentiments, the March survey found that a median of 57% in Europe said creating more jobs should be their government’s first priority, including 72% of the Spanish and 64% of the Italians and Czechs.

However, people’s intense worry about jobs and their strong desire to see government take action to increase employment did not translate into support for more government spending to stimulate the economy. A median of just 29% across Europe said they wanted to see increased public outlays as a means of solving their country’s economic problems; only in Greece did a majority (56%) advocate more spending. In France, which in 2012 elected a socialist government, just 18% backed a Keynesian solution to their woes.

So this is the conundrum European politicians and policymakers face. Their publics are crying out for action on jobs, but they also want to cut public spending.

See our survey: The New Sick Man of Europe: the European Union