When researchers try to measure “social trust,” they almost always find young adults at or near the bottom of the scale. In a Pew Research survey from April 2012, for example, only 29% of people aged 18-29 said most people could be trusted, versus 37% of all respondents. But ask them about trusting specific individuals or institutions, and a different picture emerges.

When researchers try to measure “social trust,” they almost always find young adults at or near the bottom of the scale. In a Pew Research survey from April 2012, for example, only 29% of people aged 18-29 said most people could be trusted, versus 37% of all respondents. But ask them about trusting specific individuals or institutions, and a different picture emerges.

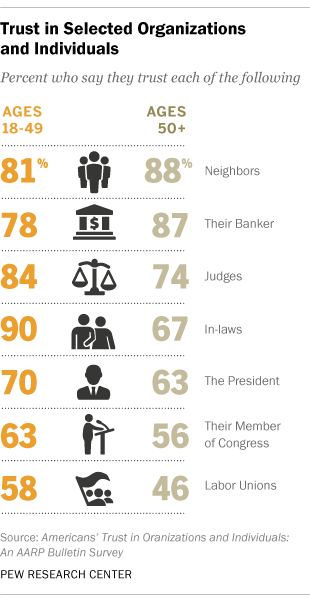

Consider a survey on trust conducted earlier this year for the AARP Bulletin. Not surprisingly, people said they trusted their nearest and dearest (spouses, friends, neighbors) the most, while such usual suspects as reporters, labor unions, CEOs and used-car salespeople were at or near the bottom.

But compared with people ages 50 and older, younger adults were significantly more likely to trust public officials (judges, the President, their member of Congress), labor unions and, oddly enough, their in-laws, while they were less likely than the older group to trust their bankers or their neighbors.

Those findings parallel a 2011 Pew Research survey that asked people how much they trusted the information they got from various sources. In that study, young adults were significantly more likely than the general population to trust the Obama administration (61% versus 50%), federal agencies (53% versus 44%) and even Congress (45% versus 37%), though they were less likely to trust information from corporations (34% versus 41%).

Young adults also are more likely to trust what the federal government does. According to a January 2013 Pew Research survey, 35% of 18- to 29-year-olds said they trusted the federal government to do the right thing all or most of the time; less than a quarter of all other age groups said so. And only 22% of 18- to 29-year-olds said the federal government posed a major threat to their personal rights and freedoms, the lowest level of any age group.

Sociologists, economists and other researchers care a lot about what they call “social trust” — the belief that people are by and large honest and can be relied on to carry out their obligations. As James S. Coleman argued as early as 1988, social trust is an essential component of social capital: Everything from simple markets to complex governmental structures works more smoothly and efficiently when people trust each other to do the right thing (or at least most people most of the time).