by Jodie T. Allen, Senior Editor, Pew Research Center

March 25, 2011 marks the 100-year anniversary of the notorious Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, a disaster widely credited with strengthening the still nascent labor union movement in the United States.1 Francis Perkins, later Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary of labor, and the first woman appointed to a cabinet position, happened upon the scene of the fire as workers were jumping to their deaths to escape the blaze.2 Perkins later called it “the day the New Deal began.”

March 25, 2011 marks the 100-year anniversary of the notorious Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, a disaster widely credited with strengthening the still nascent labor union movement in the United States.1 Francis Perkins, later Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary of labor, and the first woman appointed to a cabinet position, happened upon the scene of the fire as workers were jumping to their deaths to escape the blaze.2 Perkins later called it “the day the New Deal began.”

The tragedy, the deadliest workplace disaster in New York City’s history prior to the Sept. 11, 2001 World Trade Center attacks, caused the death of 146 garment workers. Mostly young immigrant women, they died from the fire or jumped to their deaths from the top three floors of the 10-story building. Many were unable to escape the inferno because the plant’s managers had locked doors to some exits and stairwells to prevent pilferage and unauthorized breaks from work.3 “141 MEN AND GIRLS DIE IN WAIST FACTORY FIRE” read the New York Times all-caps headline on a front-page article the following day, accompanied by grisly photographs of the event and aftermath.

Perkins later served as chief investigator of the commission charged with investigating factory conditions statewide. Following on the commission’s findings, the New York State Legislature passed labor protections for women and children and created a State Department of Labor to enforce them. Labor unions gradually gained strength over the following decades and, as part of FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s, strong worker protections were enacted into federal law, including the National Labor Relations Act. But even in the depths of the Depression, substantial numbers of Americans continued to have reservations about the impact of organized labor.

Perkins later served as chief investigator of the commission charged with investigating factory conditions statewide. Following on the commission’s findings, the New York State Legislature passed labor protections for women and children and created a State Department of Labor to enforce them. Labor unions gradually gained strength over the following decades and, as part of FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s, strong worker protections were enacted into federal law, including the National Labor Relations Act. But even in the depths of the Depression, substantial numbers of Americans continued to have reservations about the impact of organized labor.

A Gallup poll in mid-1937 found 61% hoping that labor leader John L. Lewis would fail in his effort to organize Ford Motor Co. employees into a CIO labor union.4 Two years later in February 1939, Gallup found that, by a 51%-to-21% margin, the public favored requiring every union to obtain a permit from the federal government. A 1939 Roper poll found only 20% supporting always requiring workers to join unions, with 11% saying “sometimes” and 61% rejecting the idea outright.

Gallup and Roper opinion polls from the period show substantial majorities opposing mandatory union membership and favoring federal government controls on unions. In a March 1941 Gallup poll, still prior to the U.S. entry into World War II, 68% of Americans expressed the view that labor union leaders were not “helping the national defense production program as much as they should.” A 56%-majority thought business leaders were trying harder to help defense production compared with only 10% who gave labor leaders more credit for such effort.

Most tellingly, in an October poll that same year, fully 61% said they believed that many labor union leaders were communists and fully 74% deemed union leaders to be racketeers.

Still, despite these specific reservations, Gallup polls found that overall attitudes toward labor unions were positive in the late Depression years, with 72% saying they approved of unions in a 1937 poll. While that number declined to 61% in 1941, it re-climbed to a peak of 75% in a 1957 Gallup poll.

Still, despite these specific reservations, Gallup polls found that overall attitudes toward labor unions were positive in the late Depression years, with 72% saying they approved of unions in a 1937 poll. While that number declined to 61% in 1941, it re-climbed to a peak of 75% in a 1957 Gallup poll.

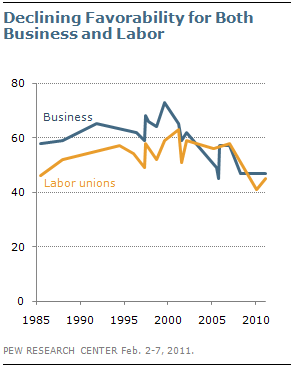

In subsequent years, support for unions, while generally positive, bobbed up and down. Gallup union-approval readings fell into the 50%-range in the high-inflation years of 1979 and 1981, but rebounded in the prosperous late 1990s, hitting a peak of 66% by the turn of the century. Similarly, Pew Research polls recorded attitudes toward labor unions peaking at 63% positive in March 2001.

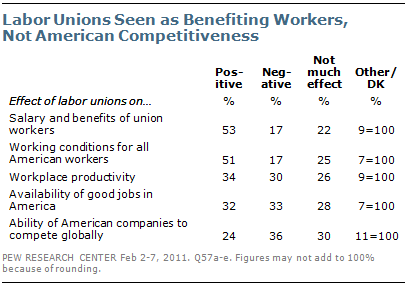

More recently, as the economy has faltered, unions have lost support among the public. In 2009, Gallup found union approval dropping to 48%, an all-time low in its series dating back to the 1930s. Majorities in a February 2011 Pew Research survey still saw unions as having positive effects on the salary and benefits of covered workers (53%) as well as on working conditions for all American workers (51%) — although responses were divided on whether unions have a positive or negative effect on workplace productivity (34% to 30%) and increase the availability of good jobs in the U.S. (32% to 33%).

More recently, as the economy has faltered, unions have lost support among the public. In 2009, Gallup found union approval dropping to 48%, an all-time low in its series dating back to the 1930s. Majorities in a February 2011 Pew Research survey still saw unions as having positive effects on the salary and benefits of covered workers (53%) as well as on working conditions for all American workers (51%) — although responses were divided on whether unions have a positive or negative effect on workplace productivity (34% to 30%) and increase the availability of good jobs in the U.S. (32% to 33%).

Most tellingly, however, the survey found only 45% expressing an overall favorable view of labor unions — close to the lowest level in a quarter century — while 41% held an unfavorable view. And while an early-March Pew Research survey found that the confrontation between public sector unions and Wisconsin’s governor appears to have strengthened support among those already holding a favorable view of labor unions (the percentage holding a very favorable view as opposed to a mostly favorable view rose seven points, with the increase concentrated among liberal Democrats and union households), the overall balance of positive and negative views remained unaltered.

Most tellingly, however, the survey found only 45% expressing an overall favorable view of labor unions — close to the lowest level in a quarter century — while 41% held an unfavorable view. And while an early-March Pew Research survey found that the confrontation between public sector unions and Wisconsin’s governor appears to have strengthened support among those already holding a favorable view of labor unions (the percentage holding a very favorable view as opposed to a mostly favorable view rose seven points, with the increase concentrated among liberal Democrats and union households), the overall balance of positive and negative views remained unaltered.

Still, the legacy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory disaster lives on in the vastly improved working conditions and compensation of almost all Americans as well as the legislation enacted to enforce them. This advancement, Perkins observed in a 1964 lecture at Cornell University, “as I have thought of it afterwards, seems in some way to have paid the debt society owed to those children, those young people who lost their lives in the Triangle Fire. It’s their contribution to the people of New York that we have this really magnificent series of legislative acts to protect and improve the administration of the law regarding the protection of work people…”

1.Cornell University’s ILR School Kheel Center maintains an excellent website describing the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the conditions in the garment and other industries at that time it, and subsequent legislation and union activities that sought to prevent its recurrence. In honor of the 100-year anniversary of the fire, the site has been redesigned and many new and updated materials have been included.

2. Many years later in a 1964 lecture at Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Francis Perkins described her witnessing of the debacle, “I happened to have been visiting a friend [nearby] and we heard the engines and we heard the screams and rushed out and rushed over where we could see what the trouble was. We could see this building from Washington Square and the people had just begun to jump when we got there. They had been holding until that time, standing in the windowsills, being crowded by others behind them, the fire pressing closer and closer, the smoke closer and closer. Finally the men were trying to get out this thing that the firemen carry with them, a net to catch people if they do jump, there were trying to get that out and they couldn’t wait any longer. They began to jump. The window was too crowded and they would jump and they hit the sidewalk…. [T]he weight of the bodies was so great, at the speed at which they were traveling that they broke through the net. Every one of them was killed, everybody who jumped was killed. It was a horrifying spectacle.”

3. As Perkins recalled, the door to one possible escape route to the roof “had been locked by the employer himself because he feared that on a Saturday afternoon which he was working just before Easter on a lot of shirtwaists for the market, he feared that some of the people in the shop might stroll out over the roof exit with a few shirtwaists rolled up under their jackets or that somebody might come in and take a few shirtwaists. In other words, he was — I only know what he said on the stand — he was afraid he would be robbed either by his employees or by the outsider. Not so much by the outsider, mostly afraid of his employees.”

4. Unless otherwise indicated, historical public opinion polls cited were obtained from the Roper Center Public Opinion Archives.