by Jodie T. Allen, Senior Editor, Pew Research Center

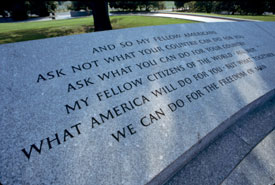

On the snow-laden morning of January 21, 1961, John F. Kennedy asked the American people to stiffen their upper lips and tighten their belts. “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country,” the new president intoned. His call to sacrifice earned near-universal praise.

“The reaction to President Kennedy’s inaugural speech was even more remarkable than the speech itself. Everybody praised it….” wrote New York Times columnist James Reston. “A president of spirit attuned to our times,” judged the Pittsburgh Press. “About as good a start as a President of the United States could make…. We doubt that any peacetime president has ever begun by engaging the people so sternly to their duties, opined the Los Angeles Times.

The reaction abroad was no less effusive. The address “demands efforts and sacrifices without shying away from mentioning the dangers and goals of the future,” applauded the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. “It was the word of a courageous man speaking to a courageous people,” marveled the Corriere Della Sera in Milan, Italy.

As for the American people, to whom the directive to “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship,” was directed, they seemed unfazed by the injunction. In a Gallup poll conducted shortly before the inauguration, nearly 70% expressed approval of Kennedy’s dealing with problems subsequent to his November election. Once in office, the new president’s approval rating continued to climb, peaking at 83% in the spring of 1961 and remaining in the high 70s or at 80% over the following year.

True, when asked by Gallup in February 1961 if they could “think of anything you could do for your country,” 41% offered no ideas at all. The most frequent response, expressed by 27%, fell under the rather vague rubric of “be a good citizen, obey laws, be honest, moral, etc.” Only 5% volunteered that they could pay more taxes or take lower wages, while 3% suggested joining the armed forces.

But two years later, when asked whether it was more important for Congress to pass legislation to cut federal income taxes “in order to increase business activity” or to balance the federal budget, by a 50%-to-35% margin the public opted for budget balancing. (This despite the fact that income taxes claimed a significantly higher proportion of national output than they have in recent years, with marginal tax rates on individuals as high as 91%.)

Since then the word “sacrifice” has all but disappeared from the political lexicon. Thus far in the current economic crisis, the emphasis supplied by political leaders, including the president elect, has been on the types of relief that government spending might provide to hardpressed financial institutions, homeowners and the unemployed. And it is difficult to gauge how the U.S. public might react should they now be confronted by a Kennedy-like exhortation. In part that is because mentions of sacrifice have also become a relative rarity in the pollsters’ lexicon as well. A recent scan of the database maintained by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research turns up remarkably few occurrences of the word in surveys conducted over the last eight years.

This does not mean that Americans feel that they have been immune to self-deprivation. When asked in an NBC/Wall Street Journal poll in January 2007 whether, with respect to the Iraq war, “the average American citizen has been asked to sacrifice or personally give up anything, or not,” the public split evenly, about half (49%) said yes and 48% said no. Asked the same question in a CBS/New York Times poll in December 2007, but with regard to the war on terrorism, 49% said no but about as many, 46%, said yes.

In fact, relatively few Americans have been personally touched by the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Only a quarter of Americans (27%) in an April 2007 Pew Research survey1 said they know someone very well who has served in either war and only about 8% say it is a family member. Nor have all Americans been equally affected. Young Americans, those ages 18 to 29, are far more likely to have had a close friend or family member serve in the military (38%) than are those over the age of 65 (19%). And only one-in-five college graduates (21%) know someone very well who has served.

At the same time, recent opinion research finds — at least in terms of American checkbooks — rising expectations with respect to comfort and convenience. A December 2006 Pew Research Center Social & Demographic Trends poll found that the number of things U.S. adults now regard as necessities rather than luxuries — from televisions to cell phones to air-conditioning — has multiplied just in the past decade.2

Still, on those few occasions, when Americans are specifically asked, many opt for sacrifice over self-indulgence. A 42%-plurality, in an August 2007 Princeton Survey Research/Newsweek poll, expressed a willingness to absorb high economic costs for the sake of addressing climate change and global warming, and a few other surveys mention the potential sacrifice of clean air and water in the context of the possible need for environmental regulations. In an August 2008 Pew Research Center for the People & the Press survey3, nearly two-thirds of Americans (63%) said they would favor a government guarantee of universal health insurance, even if it meant raising taxes.

The one sacrifice Americans repeatedly say they are willing to make (in several Fox News/Opinion Dynamic polls) is to “give up some of your personal freedom in order to reduce the threat of terrorism.” Interestingly, it was in defense of that very freedom that Kennedy exhorted his fellow Americans to sacrifice.

Notes

1 “Closeness to Troops Boosts Support for War — but Not By Much,” May 9, 2007.

2 “Luxury or Necessity?Things We Can’t Live Without: The List Has Grown in the Past Decade,” Dec. 14, 2006.

3 “More Americans Question Religion’s Role In Politics: Issues and the 2008 Election,” Aug. 21, 2008.