Crafting survey questions about geopolitics can be difficult, particularly if one is interested in learning how people would respond to a hypothetical, as-yet unrealized situation. Pew Research Center has done this in the past by asking people in NATO member states about Article 5 of the NATO treaty: specifically, whether their country should use force to defend a NATO ally if that ally got into a serious military conflict with Russia. But as the current war between Ukraine and Russia highlights, the complexities of how a conflict breaks out – e.g., who is seen as the aggressor, whether an incursion is seen as provoked, whether “defending” an ally should involve boots on the ground – can affect public attitudes.

Given these concerns, how might wording affect responses to a question about a hypothetical conflict between China and Taiwan? We decided to find out by testing multiple formulations in an experiment using a non-representative, opt-in online survey panel with American adults.

We wanted to understand a few things through this experiment. First, if we simply described a hypothetical clash between China and Taiwan as a “military conflict” – as we did in the case of the NATO question above – would people think about the question similarly or differently from a question that asks about a specific aggressor, such as China invading Taiwan? Second, given the carefully calibrated “status quo” balance across the Taiwan Strait, we wanted to understand how Americans might respond to a hypothetical situation in which China invades Taiwan, versus one in which China invades Taiwan following a declaration of independence by Taiwan.

To investigate these ideas, we randomly assigned the following three questions to respondents in the United States:

- If there were a military conflict between China and Taiwan, do you think our country should support China, support Taiwan or remain neutral? (We’ll refer to this question as “Conflict.”)

- If China invaded Taiwan, resulting in a military conflict, do you think our country should support China, support Taiwan or remain neutral? (We’ll refer to this question as “Invade.”)

- If China invaded Taiwan after Taiwan declared independence, do you think our country should support China, support Taiwan or remain neutral? (We’ll refer to this question as “Declare.”)

For each of these questions, we randomized the top two response options, meaning that some respondents saw the “support China” option first and others saw the “support Taiwan” option first. We consistently placed the “remain neutral” option at the bottom of the list of responses.

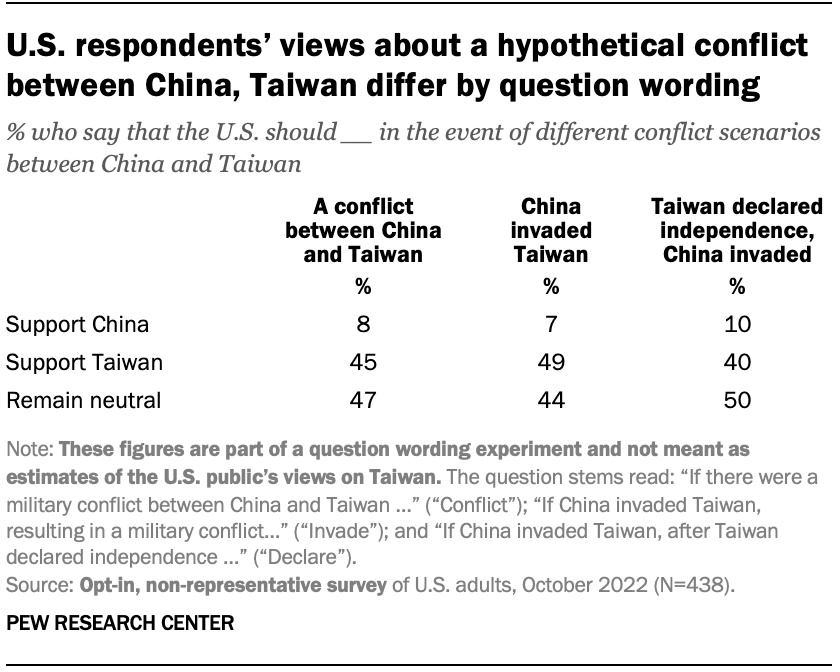

Results of the experiment indicate that participants do differentiate between these scenarios. When responding to the first question about a more generic “military conflict,” respondents are divided over remaining neutral (47%) and supporting Taiwan (45%). Very few choose the option of supporting China (8%).

When China is described as invading Taiwan, however, respondents are slightly more likely to want to support Taiwan (49%) than to remain neutral (44%). Again, very few choose the option of supporting China (7%).

The picture changes again when people are asked about a Chinese invasion that follows a declaration of independence by Taiwan. In this hypothetical, there is a slightly greater preference for neutrality (50%) over siding with Taiwan (40%). Only one-in-ten choose to support China.

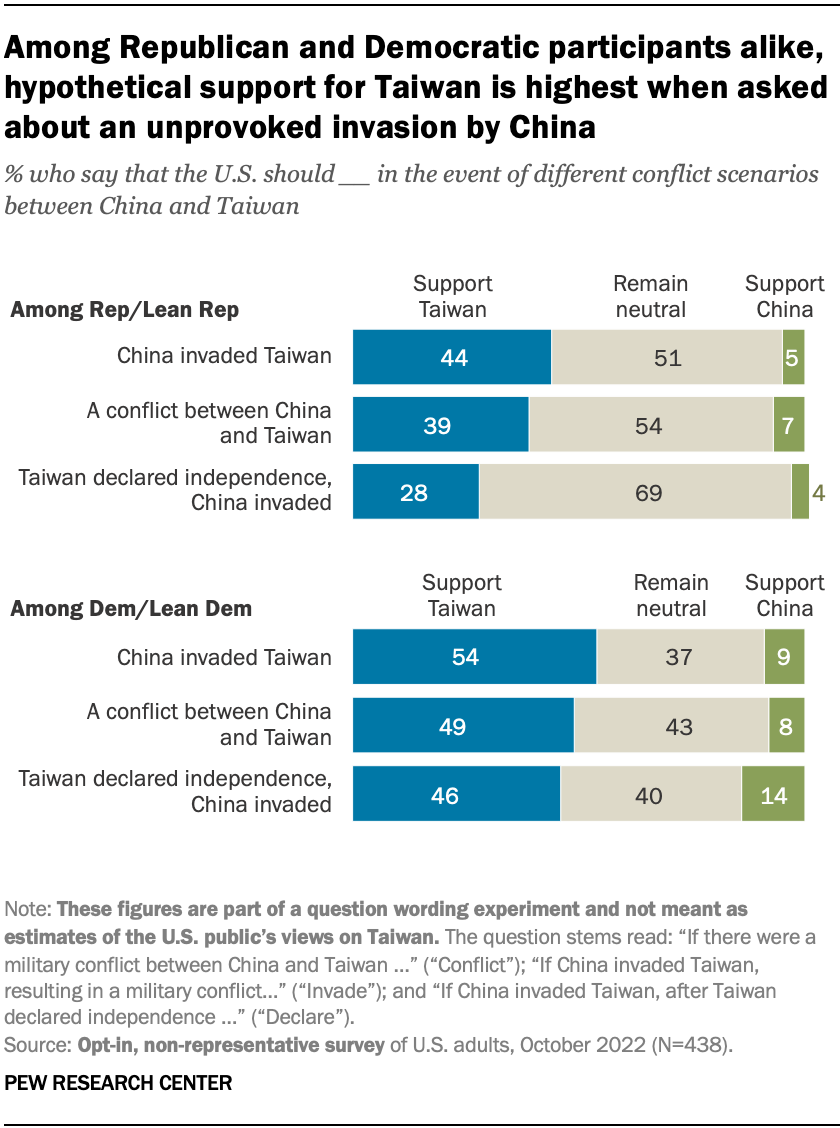

It’s even clearer that preferences differ across these conditions when one looks at who prefers which option. Take partisanship as an example: Across all three questions, Democratic and Democratic-leaning independent respondents are somewhat more likely than Republican and Republican-leaning respondents to support Taiwan. But the gap between the parties is widest when the scenario involves Taiwan declaring independence. Under this hypothetical, 46% of Democratic respondents say the U.S. should support Taiwan, compared with 28% of Republicans.

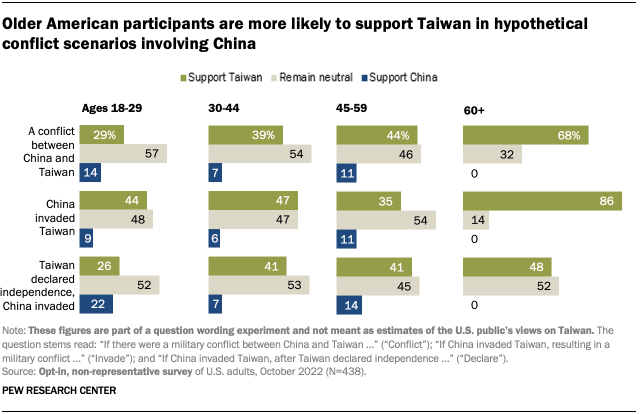

There are also notable differences by age. Across all three scenarios, respondents under 30 have a slight preference for remaining neutral. But when they are presented with the hypothetical that China has invaded Taiwan without Taiwan having first declared independence, far more of these younger respondents support Taiwan (44%) than under the other two hypotheticals (29% in the “Conflict” scenario and 26% in the “Declare” scenario).

Respondents ages 60 and older are also particularly likely to support Taiwan in the scenario where it has been invaded without having first declared independence: Nearly nine-in-ten (86%) take this position. Around two-thirds of these older participants (68%) also support Taiwan when they are asked about a more generic “military conflict” between Taiwan and China. Notably, however, only around half of these older adults (48%) would support Taiwan if Taiwan has first declared independence.

Taken together, the results of this analysis suggest that a single question may be insufficient to capture how people feel about “supporting Taiwan,” given that support is somewhat contingent on what type of provocation, if any, there is in a potential conflict. We will need to take these complexities into account if we try to measure attitudes on this issue moving forward.